|

Genomics

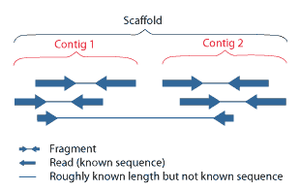

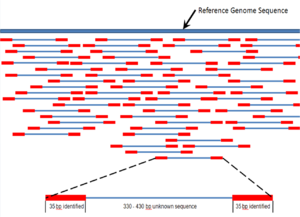

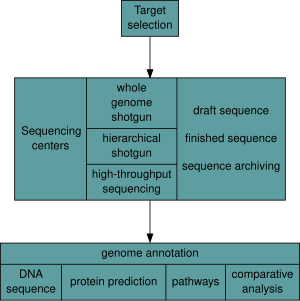

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of molecular biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, three-dimensional structural configuration.[1][2][3][4][excessive citations] In contrast to genetics, which refers to the study of individual genes and their roles in inheritance, genomics aims at the collective characterization and quantification of all of an organism's genes, their interrelations and influence on the organism.[5] Genes may direct the production of proteins with the assistance of enzymes and messenger molecules. In turn, proteins make up body structures such as organs and tissues as well as control chemical reactions and carry signals between cells. Genomics also involves the sequencing and analysis of genomes through uses of high throughput DNA sequencing and bioinformatics to assemble and analyze the function and structure of entire genomes.[6][7] Advances in genomics have triggered a revolution in discovery-based research and systems biology to facilitate understanding of even the most complex biological systems such as the brain.[8] The field also includes studies of intragenomic (within the genome) phenomena such as epistasis (effect of one gene on another), pleiotropy (one gene affecting more than one trait), heterosis (hybrid vigour), and other interactions between loci and alleles within the genome.[9] HistoryEtymologyFrom the Greek ΓΕΝ[10] gen, "gene" (gamma, epsilon, nu, epsilon) meaning "become, create, creation, birth", and subsequent variants: genealogy, genesis, genetics, genic, genomere, genotype, genus etc. While the word genome (from the German Genom, attributed to Hans Winkler) was in use in English as early as 1926,[11] the term genomics was coined by Tom Roderick, a geneticist at the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine), over beers with Jim Womack, Tom Shows and Stephen O’Brien at a meeting held in Maryland on the mapping of the human genome in 1986.[12] First as the name for a new journal and then as a whole new science discipline.[13] Early sequencing effortsFollowing Rosalind Franklin's confirmation of the helical structure of DNA, James D. Watson and Francis Crick's publication of the structure of DNA in 1953 and Fred Sanger's publication of the Amino acid sequence of insulin in 1955, nucleic acid sequencing became a major target of early molecular biologists.[14] In 1964, Robert W. Holley and colleagues published the first nucleic acid sequence ever determined, the ribonucleotide sequence of alanine transfer RNA.[15][16] Extending this work, Marshall Nirenberg and Philip Leder revealed the triplet nature of the genetic code and were able to determine the sequences of 54 out of 64 codons in their experiments.[17] In 1972, Walter Fiers and his team at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology of the University of Ghent (Ghent, Belgium) were the first to determine the sequence of a gene: the gene for Bacteriophage MS2 coat protein.[18] Fiers' group expanded on their MS2 coat protein work, determining the complete nucleotide-sequence of bacteriophage MS2-RNA (whose genome encodes just four genes in 3569 base pairs [bp]) and Simian virus 40 in 1976 and 1978, respectively.[19][20] DNA-sequencing technology developedFrederick Sanger and Walter Gilbert shared half of the 1980 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for Independently developing methods for the sequencing of DNA. In addition to his seminal work on the amino acid sequence of insulin, Frederick Sanger and his colleagues played a key role in the development of DNA sequencing techniques that enabled the establishment of comprehensive genome sequencing projects.[9] In 1975, he and Alan Coulson published a sequencing procedure using DNA polymerase with radiolabelled nucleotides that he called the Plus and Minus technique.[21][22] This involved two closely related methods that generated short oligonucleotides with defined 3' termini. These could be fractionated by electrophoresis on a polyacrylamide gel (called polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) and visualised using autoradiography. The procedure could sequence up to 80 nucleotides in one go and was a big improvement, but was still very laborious. Nevertheless, in 1977 his group was able to sequence most of the 5,386 nucleotides of the single-stranded bacteriophage φX174, completing the first fully sequenced DNA-based genome.[23] The refinement of the Plus and Minus method resulted in the chain-termination, or Sanger method (see below), which formed the basis of the techniques of DNA sequencing, genome mapping, data storage, and bioinformatic analysis most widely used in the following quarter-century of research.[24][25] In the same year Walter Gilbert and Allan Maxam of Harvard University independently developed the Maxam-Gilbert method (also known as the chemical method) of DNA sequencing, involving the preferential cleavage of DNA at known bases, a less efficient method.[26][27] For their groundbreaking work in the sequencing of nucleic acids, Gilbert and Sanger shared half the 1980 Nobel Prize in chemistry with Paul Berg (recombinant DNA). Complete genomesThe advent of these technologies resulted in a rapid intensification in the scope and speed of completion of genome sequencing projects. The first complete genome sequence of a eukaryotic organelle, the human mitochondrion (16,568 bp, about 16.6 kb [kilobase]), was reported in 1981,[28] and the first chloroplast genomes followed in 1986.[29][30] In 1992, the first eukaryotic chromosome, chromosome III of brewer's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (315 kb) was sequenced.[31] The first free-living organism to be sequenced was that of Haemophilus influenzae (1.8 Mb [megabase]) in 1995.[32] The following year a consortium of researchers from laboratories across North America, Europe, and Japan announced the completion of the first complete genome sequence of a eukaryote, S. cerevisiae (12.1 Mb), and since then genomes have continued being sequenced at an exponentially growing pace.[33] As of October 2011[update], the complete sequences are available for: 2,719 viruses, 1,115 archaea and bacteria, and 36 eukaryotes, of which about half are fungi.[34][35]  Most of the microorganisms whose genomes have been completely sequenced are problematic pathogens, such as Haemophilus influenzae, which has resulted in a pronounced bias in their phylogenetic distribution compared to the breadth of microbial diversity.[36][37] Of the other sequenced species, most were chosen because they were well-studied model organisms or promised to become good models. Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) has long been an important model organism for the eukaryotic cell, while the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster has been a very important tool (notably in early pre-molecular genetics). The worm Caenorhabditis elegans is an often used simple model for multicellular organisms. The zebrafish Brachydanio rerio is used for many developmental studies on the molecular level, and the plant Arabidopsis thaliana is a model organism for flowering plants. The Japanese pufferfish (Takifugu rubripes) and the spotted green pufferfish (Tetraodon nigroviridis) are interesting because of their small and compact genomes, which contain very little noncoding DNA compared to most species.[38][39] The mammals dog (Canis familiaris),[40] brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), mouse (Mus musculus), and chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) are all important model animals in medical research.[27] A rough draft of the human genome was completed by the Human Genome Project in early 2001, creating much fanfare.[41] This project, completed in 2003, sequenced the entire genome for one specific person, and by 2007 this sequence was declared "finished" (less than one error in 20,000 bases and all chromosomes assembled).[41] In the years since then, the genomes of many other individuals have been sequenced, partly under the auspices of the 1000 Genomes Project, which announced the sequencing of 1,092 genomes in October 2012.[42] Completion of this project was made possible by the development of dramatically more efficient sequencing technologies and required the commitment of significant bioinformatics resources from a large international collaboration.[43] The continued analysis of human genomic data has profound political and social repercussions for human societies.[44] The "omics" revolution The English-language neologism omics informally refers to a field of study in biology ending in -omics, such as genomics, proteomics or metabolomics. The related suffix -ome is used to address the objects of study of such fields, such as the genome, proteome, or metabolome (lipidome) respectively. The suffix -ome as used in molecular biology refers to a totality of some sort; similarly omics has come to refer generally to the study of large, comprehensive biological data sets. While the growth in the use of the term has led some scientists (Jonathan Eisen, among others[45]) to claim that it has been oversold,[46] it reflects the change in orientation towards the quantitative analysis of complete or near-complete assortment of all the constituents of a system.[47] In the study of symbioses, for example, researchers which were once limited to the study of a single gene product can now simultaneously compare the total complement of several types of biological molecules.[48][49] Genome analysisAfter an organism has been selected, genome projects involve three components: the sequencing of DNA, the assembly of that sequence to create a representation of the original chromosome, and the annotation and analysis of that representation.[9]  SequencingHistorically, sequencing was done in sequencing centers, centralized facilities (ranging from large independent institutions such as Joint Genome Institute which sequence dozens of terabases a year, to local molecular biology core facilities) which contain research laboratories with the costly instrumentation and technical support necessary. As sequencing technology continues to improve, however, a new generation of effective fast turnaround benchtop sequencers has come within reach of the average academic laboratory.[50][51] On the whole, genome sequencing approaches fall into two broad categories, shotgun and high-throughput (or next-generation) sequencing.[9] Shotgun sequencing Shotgun sequencing is a sequencing method designed for analysis of DNA sequences longer than 1000 base pairs, up to and including entire chromosomes.[52] It is named by analogy with the rapidly expanding, quasi-random firing pattern of a shotgun. Since gel electrophoresis sequencing can only be used for fairly short sequences (100 to 1000 base pairs), longer DNA sequences must be broken into random small segments which are then sequenced to obtain reads. Multiple overlapping reads for the target DNA are obtained by performing several rounds of this fragmentation and sequencing. Computer programs then use the overlapping ends of different reads to assemble them into a continuous sequence.[52][53] Shotgun sequencing is a random sampling process, requiring over-sampling to ensure a given nucleotide is represented in the reconstructed sequence; the average number of reads by which a genome is over-sampled is referred to as coverage.[54] For much of its history, the technology underlying shotgun sequencing was the classical chain-termination method or 'Sanger method', which is based on the selective incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides by DNA polymerase during in vitro DNA replication.[23][55] Recently, shotgun sequencing has been supplanted by high-throughput sequencing methods, especially for large-scale, automated genome analyses. However, the Sanger method remains in wide use, primarily for smaller-scale projects and for obtaining especially long contiguous DNA sequence reads (>500 nucleotides).[56] Chain-termination methods require a single-stranded DNA template, a DNA primer, a DNA polymerase, normal deoxynucleosidetriphosphates (dNTPs), and modified nucleotides (dideoxyNTPs) that terminate DNA strand elongation. These chain-terminating nucleotides lack a 3'-OH group required for the formation of a phosphodiester bond between two nucleotides, causing DNA polymerase to cease extension of DNA when a ddNTP is incorporated. The ddNTPs may be radioactively or fluorescently labelled for detection in DNA sequencers.[9] Typically, these machines can sequence up to 96 DNA samples in a single batch (run) in up to 48 runs a day.[57] High-throughput sequencingThe high demand for low-cost sequencing has driven the development of high-throughput sequencing technologies that parallelize the sequencing process, producing thousands or millions of sequences at once.[58][59] High-throughput sequencing is intended to lower the cost of DNA sequencing beyond what is possible with standard dye-terminator methods. In ultra-high-throughput sequencing, as many as 500,000 sequencing-by-synthesis operations may be run in parallel.[60][61]  The Illumina dye sequencing method is based on reversible dye-terminators and was developed in 1996 at the Geneva Biomedical Research Institute, by Pascal Mayer and Laurent Farinelli.[62] In this method, DNA molecules and primers are first attached on a slide and amplified with polymerase so that local clonal colonies, initially coined "DNA colonies", are formed. To determine the sequence, four types of reversible terminator bases (RT-bases) are added and non-incorporated nucleotides are washed away. Unlike pyrosequencing, the DNA chains are extended one nucleotide at a time and image acquisition can be performed at a delayed moment, allowing for very large arrays of DNA colonies to be captured by sequential images taken from a single camera. Decoupling the enzymatic reaction and the image capture allows for optimal throughput and theoretically unlimited sequencing capacity; with an optimal configuration, the ultimate throughput of the instrument depends only on the A/D conversion rate of the camera. The camera takes images of the fluorescently labeled nucleotides, then the dye along with the terminal 3' blocker is chemically removed from the DNA, allowing the next cycle.[63] An alternative approach, ion semiconductor sequencing, is based on standard DNA replication chemistry. This technology measures the release of a hydrogen ion each time a base is incorporated. A microwell containing template DNA is flooded with a single nucleotide, if the nucleotide is complementary to the template strand it will be incorporated and a hydrogen ion will be released. This release triggers an ISFET ion sensor. If a homopolymer is present in the template sequence multiple nucleotides will be incorporated in a single flood cycle, and the detected electrical signal will be proportionally higher.[64] AssemblySequence assembly refers to aligning and merging fragments of a much longer DNA sequence in order to reconstruct the original sequence.[9] This is needed as current DNA sequencing technology cannot read whole genomes as a continuous sequence, but rather reads small pieces of between 20 and 1000 bases, depending on the technology used. Third generation sequencing technologies such as PacBio or Oxford Nanopore routinely generate sequencing reads 10-100 kb in length; however, they have a high error rate at approximately 1 percent.[65][66] Typically the short fragments, called reads, result from shotgun sequencing genomic DNA, or gene transcripts (ESTs).[9] Assembly approachesAssembly can be broadly categorized into two approaches: de novo assembly, for genomes which are not similar to any sequenced in the past, and comparative assembly, which uses the existing sequence of a closely related organism as a reference during assembly.[54] Relative to comparative assembly, de novo assembly is computationally difficult (NP-hard), making it less favourable for short-read NGS technologies. Within the de novo assembly paradigm there are two primary strategies for assembly, Eulerian path strategies, and overlap-layout-consensus (OLC) strategies. OLC strategies ultimately try to create a Hamiltonian path through an overlap graph which is an NP-hard problem. Eulerian path strategies are computationally more tractable because they try to find a Eulerian path through a deBruijn graph.[54] FinishingFinished genomes are defined as having a single contiguous sequence with no ambiguities representing each replicon.[67] AnnotationThe DNA sequence assembly alone is of little value without additional analysis.[9] Genome annotation is the process of attaching biological information to sequences, and consists of three main steps:[68]

Automatic annotation tools try to perform these steps in silico, as opposed to manual annotation (a.k.a. curation) which involves human expertise and potential experimental verification.[69] Ideally, these approaches co-exist and complement each other in the same annotation pipeline (also see below). Traditionally, the basic level of annotation is using BLAST for finding similarities, and then annotating genomes based on homologues.[9] More recently, additional information is added to the annotation platform. The additional information allows manual annotators to deconvolute discrepancies between genes that are given the same annotation. Some databases use genome context information, similarity scores, experimental data, and integrations of other resources to provide genome annotations through their Subsystems approach. Other databases (e.g. Ensembl) rely on both curated data sources as well as a range of software tools in their automated genome annotation pipeline.[70] Structural annotation consists of the identification of genomic elements, primarily ORFs and their localisation, or gene structure. Functional annotation consists of attaching biological information to genomic elements. Sequencing pipelines and databasesThe need for reproducibility and efficient management of the large amount of data associated with genome projects mean that computational pipelines have important applications in genomics.[71] Research areasFunctional genomicsFunctional genomics is a field of molecular biology that attempts to make use of the vast wealth of data produced by genomic projects (such as genome sequencing projects) to describe gene (and protein) functions and interactions. Functional genomics focuses on the dynamic aspects such as gene transcription, translation, and protein–protein interactions, as opposed to the static aspects of the genomic information such as DNA sequence or structures. Functional genomics attempts to answer questions about the function of DNA at the levels of genes, RNA transcripts, and protein products. A key characteristic of functional genomics studies is their genome-wide approach to these questions, generally involving high-throughput methods rather than a more traditional "gene-by-gene" approach. A major branch of genomics is still concerned with sequencing the genomes of various organisms, but the knowledge of full genomes has created the possibility for the field of functional genomics, mainly concerned with patterns of gene expression during various conditions. The most important tools here are microarrays and bioinformatics. Structural genomics Structural genomics seeks to describe the 3-dimensional structure of every protein encoded by a given genome.[72][73] This genome-based approach allows for a high-throughput method of structure determination by a combination of experimental and modeling approaches. The principal difference between structural genomics and traditional structural prediction is that structural genomics attempts to determine the structure of every protein encoded by the genome, rather than focusing on one particular protein. With full-genome sequences available, structure prediction can be done more quickly through a combination of experimental and modeling approaches, especially because the availability of large numbers of sequenced genomes and previously solved protein structures allow scientists to model protein structure on the structures of previously solved homologs. Structural genomics involves taking a large number of approaches to structure determination, including experimental methods using genomic sequences or modeling-based approaches based on sequence or structural homology to a protein of known structure or based on chemical and physical principles for a protein with no homology to any known structure. As opposed to traditional structural biology, the determination of a protein structure through a structural genomics effort often (but not always) comes before anything is known regarding the protein function. This raises new challenges in structural bioinformatics, i.e. determining protein function from its 3D structure.[74] EpigenomicsEpigenomics is the study of the complete set of epigenetic modifications on the genetic material of a cell, known as the epigenome.[75] Epigenetic modifications are reversible modifications on a cell's DNA or histones that affect gene expression without altering the DNA sequence (Russell 2010 p. 475). Two of the most characterized epigenetic modifications are DNA methylation and histone modification.[76] Epigenetic modifications play an important role in gene expression and regulation, and are involved in numerous cellular processes such as in differentiation/development[77] and tumorigenesis.[75] The study of epigenetics on a global level has been made possible only recently through the adaptation of genomic high-throughput assays.[78] Metagenomics Metagenomics is the study of metagenomes, genetic material recovered directly from environmental samples. The broad field may also be referred to as environmental genomics, ecogenomics or community genomics. While traditional microbiology and microbial genome sequencing rely upon cultivated clonal cultures, early environmental gene sequencing cloned specific genes (often the 16S rRNA gene) to produce a profile of diversity in a natural sample. Such work revealed that the vast majority of microbial biodiversity had been missed by cultivation-based methods.[79] Recent studies use "shotgun" Sanger sequencing or massively parallel pyrosequencing to get largely unbiased samples of all genes from all the members of the sampled communities.[80] Because of its power to reveal the previously hidden diversity of microscopic life, metagenomics offers a powerful lens for viewing the microbial world that has the potential to revolutionize understanding of the entire living world.[81][82] Model systemsViruses and bacteriophagesBacteriophages have played and continue to play a key role in bacterial genetics and molecular biology. Historically, they were used to define gene structure and gene regulation. Also the first genome to be sequenced was a bacteriophage. However, bacteriophage research did not lead the genomics revolution, which is clearly dominated by bacterial genomics. Only very recently has the study of bacteriophage genomes become prominent, thereby enabling researchers to understand the mechanisms underlying phage evolution. Bacteriophage genome sequences can be obtained through direct sequencing of isolated bacteriophages, but can also be derived as part of microbial genomes. Analysis of bacterial genomes has shown that a substantial amount of microbial DNA consists of prophage sequences and prophage-like elements.[83] A detailed database mining of these sequences offers insights into the role of prophages in shaping the bacterial genome: Overall, this method verified many known bacteriophage groups, making this a useful tool for predicting the relationships of prophages from bacterial genomes.[84][85] CyanobacteriaAt present there are 24 cyanobacteria for which a total genome sequence is available. 15 of these cyanobacteria come from the marine environment. These are six Prochlorococcus strains, seven marine Synechococcus strains, Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 and Crocosphaera watsonii WH8501. Several studies have demonstrated how these sequences could be used very successfully to infer important ecological and physiological characteristics of marine cyanobacteria. However, there are many more genome projects currently in progress, amongst those there are further Prochlorococcus and marine Synechococcus isolates, Acaryochloris and Prochloron, the N2-fixing filamentous cyanobacteria Nodularia spumigena, Lyngbya aestuarii and Lyngbya majuscula, as well as bacteriophages infecting marine cyanobaceria. Thus, the growing body of genome information can also be tapped in a more general way to address global problems by applying a comparative approach. Some new and exciting examples of progress in this field are the identification of genes for regulatory RNAs, insights into the evolutionary origin of photosynthesis, or estimation of the contribution of horizontal gene transfer to the genomes that have been analyzed.[86] Applications Genomics has provided applications in many fields, including medicine, biotechnology, anthropology and other social sciences.[44] Genomic medicineNext-generation genomic technologies allow clinicians and biomedical researchers to drastically increase the amount of genomic data collected on large study populations.[87] When combined with new informatics approaches that integrate many kinds of data with genomic data in disease research, this allows researchers to better understand the genetic bases of drug response and disease.[88][89] Early efforts to apply the genome to medicine included those by a Stanford team led by Euan Ashley who developed the first tools for the medical interpretation of a human genome.[90][91][92] The Genomes2People research program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Broad Institute and Harvard Medical School was established in 2012 to conduct empirical research in translating genomics into health. Brigham and Women's Hospital opened a Preventive Genomics Clinic in August 2019, with Massachusetts General Hospital following a month later.[93][94] The All of Us research program aims to collect genome sequence data from 1 million participants to become a critical component of the precision medicine research platform[95] and the UK Biobank initiative has studied more than 500.000 individuals with deep genomic and phenotypic data.[96] Synthetic biology and bioengineeringThe growth of genomic knowledge has enabled increasingly sophisticated applications of synthetic biology.[97] In 2010 researchers at the J. Craig Venter Institute announced the creation of a partially synthetic species of bacterium, Mycoplasma laboratorium, derived from the genome of Mycoplasma genitalium.[98] Population and conservation genomicsPopulation genomics has developed as a popular field of research, where genomic sequencing methods are used to conduct large-scale comparisons of DNA sequences among populations - beyond the limits of genetic markers such as short-range PCR products or microsatellites traditionally used in population genetics. Population genomics studies genome-wide effects to improve our understanding of microevolution so that we may learn the phylogenetic history and demography of a population.[99] Population genomic methods are used for many different fields including evolutionary biology, ecology, biogeography, conservation biology and fisheries management. Similarly, landscape genomics has developed from landscape genetics to use genomic methods to identify relationships between patterns of environmental and genetic variation. Conservationists can use the information gathered by genomic sequencing in order to better evaluate genetic factors key to species conservation, such as the genetic diversity of a population or whether an individual is heterozygous for a recessive inherited genetic disorder.[100] By using genomic data to evaluate the effects of evolutionary processes and to detect patterns in variation throughout a given population, conservationists can formulate plans to aid a given species without as many variables left unknown as those unaddressed by standard genetic approaches.[101] See also

References

Further reading

External links

|