|

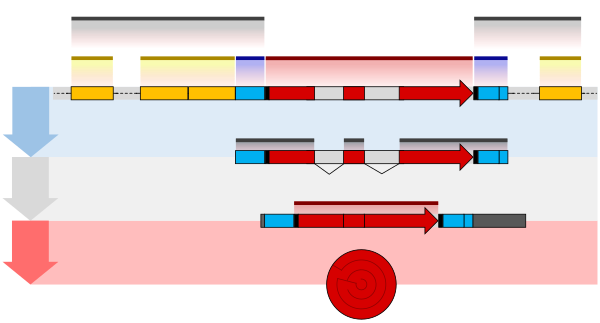

Gene structureGene structure is the organisation of specialised sequence elements within a gene. Genes contain most of the information necessary for living cells to survive and reproduce.[1][2] In most organisms, genes are made of DNA, where the particular DNA sequence determines the function of the gene. A gene is transcribed (copied) from DNA into RNA, which can either be non-coding (ncRNA) with a direct function, or an intermediate messenger (mRNA) that is then translated into protein. Each of these steps is controlled by specific sequence elements, or regions, within the gene. Every gene, therefore, requires multiple sequence elements to be functional.[2] This includes the sequence that actually encodes the functional protein or ncRNA, as well as multiple regulatory sequence regions. These regions may be as short as a few base pairs, up to many thousands of base pairs long. Much of gene structure is broadly similar between eukaryotes and prokaryotes. These common elements largely result from the shared ancestry of cellular life in organisms over 2 billion years ago.[3] Key differences in gene structure between eukaryotes and prokaryotes reflect their divergent transcription and translation machinery.[4][5] Understanding gene structure is the foundation of understanding gene annotation, expression, and function.[6] Common featuresThe structures of both eukaryotic and prokaryotic genes involve several nested sequence elements. Each element has a specific function in the multi-step process of gene expression. The sequences and lengths of these elements vary, but the same general functions are present in most genes.[2] Although DNA is a double-stranded molecule, typically only one of the strands encodes information that the RNA polymerase reads to produce protein-coding mRNA or non-coding RNA. This 'sense' or 'coding' strand, runs in the 5' to 3' direction where the numbers refer to the carbon atoms of the backbone's ribose sugar. The open reading frame (ORF) of a gene is therefore usually represented as an arrow indicating the direction in which the sense strand is read.[7] Regulatory sequences are located at the extremities of genes. These sequence regions can either be next to the transcribed region (the promoter) or separated by many kilobases (enhancers and silencers).[8] The promoter is located at the 5' end of the gene and is composed of a core promoter sequence and a proximal promoter sequence. The core promoter marks the start site for transcription by binding RNA polymerase and other proteins necessary for copying DNA to RNA. The proximal promoter region binds transcription factors that modify the affinity of the core promoter for RNA polymerase.[9][10] Genes may be regulated by multiple enhancer and silencer sequences that further modify the activity of promoters by binding activator or repressor proteins.[11][12] Enhancers and silencers may be distantly located from the gene, many thousands of base pairs away. The binding of different transcription factors, therefore, regulates the rate of transcription initiation at different times and in different cells.[13] Regulatory elements can overlap one another, with a section of DNA able to interact with many competing activators and repressors as well as RNA polymerase. For example, some repressor proteins can bind to the core promoter to prevent polymerase binding.[14] For genes with multiple regulatory sequences, the rate of transcription is the product of all of the elements combined.[15] Binding of activators and repressors to multiple regulatory sequences has a cooperative effect on transcription initiation.[16] Although all organisms use both transcriptional activators and repressors, eukaryotic genes are said to be 'default off', whereas prokaryotic genes are 'default on'.[5] The core promoter of eukaryotic genes typically requires additional activation by promoter elements for expression to occur. The core promoter of prokaryotic genes, conversely, is sufficient for strong expression and is regulated by repressors.[5]

An additional layer of regulation occurs for protein coding genes after the mRNA has been processed to prepare it for translation to protein. Only the region between the start and stop codons encodes the final protein product. The flanking untranslated regions (UTRs) contain further regulatory sequences.[18] The 3' UTR contains a terminator sequence, which marks the endpoint for transcription and releases the RNA polymerase.[19] The 5’ UTR binds the ribosome, which translates the protein-coding region into a string of amino acids that fold to form the final protein product. In the case of genes for non-coding RNAs, the RNA is not translated but instead folds to be directly functional.[20][21] EukaryotesThe structure of eukaryotic genes includes features not found in prokaryotes. Most of these relate to post-transcriptional modification of pre-mRNAs to produce mature mRNA ready for translation into protein. Eukaryotic genes typically have more regulatory elements to control gene expression compared to prokaryotes.[5] This is particularly true in multicellular eukaryotes, humans for example, where gene expression varies widely among different tissues.[11] A key feature of the structure of eukaryotic genes is that their transcripts are typically subdivided into exon and intron regions. Exon regions are retained in the final mature mRNA molecule, while intron regions are spliced out (excised) during post-transcriptional processing.[22] Indeed, the intron regions of a gene can be considerably longer than the exon regions. Once spliced together, the exons form a single continuous protein-coding regions, and the splice boundaries are not detectable. Eukaryotic post-transcriptional processing also adds a 5' cap to the start of the mRNA and a poly-adenosine tail to the end of the mRNA. These additions stabilise the mRNA and direct its transport from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, although neither of these features are directly encoded in the structure of a gene.[18] ProkaryotesThe overall organisation of prokaryotic genes is markedly different from that of the eukaryotes. The most obvious difference is that prokaryotic ORFs are often grouped into a polycistronic operon under the control of a shared set of regulatory sequences. These ORFs are all transcribed onto the same mRNA and so are co-regulated and often serve related functions.[23][24] Each ORF typically has its own ribosome binding site (RBS) so that ribosomes simultaneously translate ORFs on the same mRNA. Some operons also display translational coupling, where the translation rates of multiple ORFs within an operon are linked.[25] This can occur when the ribosome remains attached at the end of an ORF and simply translocates along to the next without the need for a new RBS.[26] Translational coupling is also observed when translation of an ORF affects the accessibility of the next RBS through changes in RNA secondary structure.[27] Having multiple ORFs on a single mRNA is only possible in prokaryotes because their transcription and translation take place at the same time and in the same subcellular location.[23][28] The operator sequence next to the promoter is the main regulatory element in prokaryotes. Repressor proteins bound to the operator sequence physically obstructs the RNA polymerase enzyme, preventing transcription.[29][30] Riboswitches are another important regulatory sequence commonly present in prokaryotic UTRs. These sequences switch between alternative secondary structures in the RNA depending on the concentration of key metabolites. The secondary structures then either block or reveal important sequence regions such as RBSs. Introns are extremely rare in prokaryotes and therefore do not play a significant role in prokaryotic gene regulation.[31] References

External links

|