|

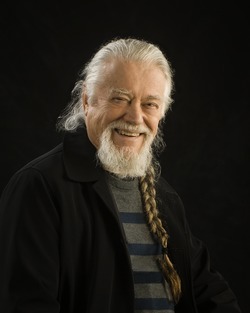

Gary Botting

Gary Norman Arthur Botting (born 19 July 1943)[1] is a Canadian legal scholar and criminal defense lawyer (now retired) as well as a poet, playwright, novelist, and critic of literature and religion, in particular Jehovah's Witnesses. The author of 40 published books,[2] he remains one of the country's leading authorities on extradition law.[3][4] He is said to have had "more experience in battling the extradition system than any other Canadian lawyer."[5][6] Early lifeBotting was born in Oakley House, Frilford, near RAF Abingdon near Oxford, England on 19 July 1943. He was christened in the Church of England Parish Church of St. James the Great in Radley, Berkshire. His father, Pilot Officer Norman Arthur Botting DFC, a Dam Buster with 617 Squadron, was killed in action over Germany on 15 September 1943 when Gary was less than two months old—on his older sister Mavis' second birthday. Following the war, their mother Joan, a teacher, took up residence with Group Captain Leonard Cheshire VC, the father of their younger sister, Elizabeth, at Gumley Hall near Market Harborough, Leicestershire[7] and later she and the children moved with Cheshire to Le Court, the mansion he had acquired from his aunt in Hampshire.[8] After witnessing the bombing of Nagasaki at the end of World War II, Cheshire, who had been raised High Anglican, began to examine various religions.[9] Joan and he agreed about the nature of God as a person.[10] Joan was baptized as a Jehovah's Witness in September 1948 and expected Cheshire to follow; when he converted to Roman Catholicism later that year instead, she moved with the children back to Radley.[11] Botting attended the Church of England Primary School in Radley. One day when pedaling back from school he found a large sphinx moth, "a rare and portentous Death's-Head Hawk (Acherontia atropos)" at the side of the road.[12] Later, in Cambridge, he began collecting moths in earnest.[13] On Elizabeth's eighth birthday, 8 January 1954, the Botting family arrived in Fort Erie, Ontario as immigrants to Canada.[1] EntomologyIn his early teens Botting began to experiment at home with the hybridization of moths, developing his own technique entailing surgical transplantation of female pheromonal scent sacs.[14] Exhibits of his hybrid moths won top honours at the Ontario (Canada) and United States National Science Fairs two years in a row—in 1960 for "Interesting Variations of the Cynthia Silk Moth", and in 1961 for "Intergeneric Hybridization Among Giant Silk Moths".[15] In particular, he cross-bred the North American Polyphemus moth (then called Telea polyphemus) with Japanese and Indian giant silk moths of the genus Antheraea, pointing out that the Polyphemus moth really belonged to that genus.[16] The Polyphemus moth was subsequently renamed Antheraea polyphemus to accord with his observations. In the summer of 1960 he was sponsored by the American Institute of Biological Sciences on a lecture tour of the US to explicate his experiments.[17] Later that year the US National Academy of Sciences sponsored him on a lecture tour of India.[18] While in India in January 1961, Botting was befriended by J. B. S. Haldane,[19] who decades earlier had applied statistical research to the natural selection of moths.[20] In the 1960s, Haldane's wife, Helen Spurway, was also researching the genetics of giant silk moths of the genus Antheraea. Helen Spurway, J.B.S. and Krishna Dronamraju were present at the Oberoi Grand Hotel in Kolkata when 1960 US National Science Fair winner in botany Susan Brown reminded the Haldanes that she and Botting had a previously scheduled event that would prevent them from accepting an invitation to a banquet proposed by J.B.S. and Helen in their honour and scheduled for that evening. After the two students had left the hotel, Haldane went on his much-publicized hunger strike to protest what he regarded as a "U.S. insult".[21] Six decades later, Botting's January 1961 encounter with Haldane and their conversations regarding the peppered moth were still generating controversy, even in the pages of the revered Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.[22] Botting received the US National Pest Control Award when he demonstrated that his experiments had practical applications beyond producing finer silk.[23] In 1964 he experimented with feeding caterpillars juvenile hormones and vitamin B12 to keep Luna moths (Actias luna) and cecropia moths (Hyalophora cecropia) in the larval stage an instar longer than normal, resulting in larger cocoons and larger adult moths.[24] ReligionBotting was raised as a Jehovah's Witness. At age five, with his sister Mavis (then seven), Botting began going from house to house distributing The Watchtower and Awake!,[25] and the following year gave his first sermon about "Noah and the Ark" at the Cambridgeshire Labour Hall in Cambridge, England.[26] Mavis and Gary attended the semi-official Theodena Kingdom Boarding School in Suffolk, run by Rhoda Ford, the sister of Percy Ford, at that time the head of Jehovah's Witnesses in Great Britain.[27] Botting later documented the harsh discipline by caning meted out to him at the hands of Ms. Ford, who had set up the school in defiance of Thorpeness bylaws; he ran away from school, and contracted double pneumonia. As a result of his mother's intervention, the school was shut down, Ms. Ford was disfellowshipped from Jehovah's Witnesses, and her brother demoted.[28] In 1953, Gary's maternal grandmother Lysbeth Turner, unimpressed by her daughter's choice of religion, attempted to expand Gary's religious horizons by introducing him to Gerald Gardner, the principal advocate of "the old religion" of Wicca to which she adhered. Botting's lay preaching continued after his arrival in Canada at age ten. He entered the "industrial arts" (rather than "academic") stream in high school, majoring in drafting and machine shop.[29] In July 1955, Botting was baptized as a "dedicated" Jehovah's Witness at a convention in New York City.[30] In July 1961, Watch Tower vice-president F.W. Franz assigned Botting the task of smuggling Watchtowers and anti-Francisco Franco tracts into Spain, where Jehovah's Witnesses were banned.[31] From 1961 to 1963, Botting volunteered in Hong Kong as a "pioneer" missionary, supporting himself by working as a journalist for the South China Morning Post.[32] Once he returned from Hong Kong, he attended Trent University to study literature and philosophy. In 1965, the Peterborough Examiner published a full-page editorial on Botting's personal dilemma, "Evolution and the Bible: Faith in Science or Faith in God a Choice for Man."[33] Botting later admitted that his discussions with Haldane in India in 1961 had had a profound effect on his way of looking at the world, although the process of shaking the social imperatives imposed by his religion took decades.[34] Disenchanted with organized Christian religion in general and Jehovah's Witnesses in particular, in 1975 Botting wrote a semi-autobiographical poem sequence[35] satirizing his experiences as a missionary and the fact that Armageddon had not arrived by October 1975 as Jehovah's Witnesses had predicted.[36] His play Whatever Happened to Saint Joanne? (1982) depicted the existential struggle and moral dilemma of leaving a fundamentalist sect.[37] Another of his plays first produced by the Department of Drama at the University of Alberta depicted the forming of a covenstead in which the protagonist priestess rejects her fundamentalist background and protects herself and those she loves with charms, spells and rituals.[38] In 1984, Gary and Heather Botting co-authored The Orwellian World of Jehovah's Witnesses,[39] an exposé of the inner workings, shifting doctrines, linguistic quirks and "mental regulating" of members of the group. It graphically compared the religion's closed social paradigms to the "Newspeak" and thought control depicted in Orwell's novel.[40] The book sold out its first edition of 5000 copies within weeks of its release.[41] In 1993, Botting published Fundamental Freedoms and Jehovah's Witnesses, an academic work about Jehovah's Witnesses in Canada and their role in pressing for the development of the Canadian Bill of Rights and what eventually became the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[42] By 1982 Botting had accepted Darwinian evolution as undeniable fact.[43] At the same time, he thoroughly excoriated the "Big Bang" theory, maintaining that Albert Einstein had prematurely deferred to Edwin Hubble's theory of an expanding universe rather than relying on his own calculations of 1907 in which he predicted a gravitational redshift, observable in every massive stellar or galactic body in space.[44] Rather than regarding himself as an essentialist like Iris Murdoch or an existentialist like Jean-Paul Sartre, Botting has described himself as an extensionist: all things, including human understanding, can be explained as extensions of mind and body in space and time.[45] Like Richard Dawkins, of whose brand of genetic theory—and unabashed atheism—Botting has been a staunch advocate, he was admittedly influenced by the observations and opinions of J. B. S. Haldane.[46] JournalistIn September 1961, Botting left Canada for Hong Kong initially to become a missionary for Jehovah's Witnesses; but he had to support himself, and soon became first a proofreader and then a full-time reporter for the South China Morning Post. This led to many adventures which he chronicled in his serialized Occupational Hazard: The Adventures of a Journalist.[47] Soon journalism became a priority and he became one of the main feature writers for the South China Sunday Post-Herald.[48] He returned to Canada and in 1964 began to work for the Peterborough Examiner,[49] then owned by Robertson Davies, at the same time attending Trent University, where he was editor of the student newspaper, Trent Trends, and literary magazine, Tridentine. He became fast friends with Farley Mowat and wrote several features about the popular author, describing their shared escapades on The Happy Adventure ("The Boat that Wouldn't Float"), including speculation as to whether sharks had invaded Lake Ontario via the newly opened St. Lawrence Seaway.[50] As an investigative reporter, in 1966 Botting opted to serve time in jail rather than pay parking fines so that he could write an exposé on security and sanitation problems at the notorious Victoria County Jail in Ontario—eventually forcing the prison to close.[51] His later work of popular history, Chief Smallboy: In Pursuit of Freedom, published in 2005 by Fifth House Books, discusses the life of mid-twentieth century Cree leader Bobtail ("Bob") Smallboy of the Ermineskin Cree Nation. Laurie Meijer-Drees, writing for The Canadian Historical Review,[52] praised the book for its use of oral history and family history in shedding more light on its subject, but criticized its portrayal of Smallboy as a "lone leader" with few peers and in particular its failure to put Smallboy in context with major First Nations political movements of the time such as the Indian Association of Alberta.[52] PoetCommencing in the 1960s, Botting published poetry in various literary magazines including Casserole, Hecate's Loom, Issue, Legal Studies Forum, New Thursday, Tridentine—and Umwelt, a Canadian literary magazine which he later satirized in BumweltS: Poems Written in Sexy '69.[53] His third collection of poems, Streaking! (1974)[54] helped popularize that fad in Canada.[55] Monomonster in Hell (1975)[56] —based loosely on Botting's experiences as a missionary in Hong Kong—satirizes the failed prophecy of Jehovah's Witnesses, who had anticipated that Armageddon would come by October 2, 1975.[57] Freckled Blue (1976),[56] Lady Godiva on a Plaster Horse (1977)[56] and Lady of My House (1986) [58] are collections of love poems which explore different poetic forms from experimental and concrete poetry to more conventional sonnets and ballads.[59] His complete published poems, including a risqué assortment that appeared in a limited edition of Isabeau: Poems of Lust and Love (2013), were gathered together in Streaking! The Collected Poems of Gary Botting (2014), edited by screenwriter Tihemme Gagnon.[60] PlaywrightBeginning as playwright in residence with People & Puppets Incorporated in Edmonton, Alberta in the 1970s, Botting wrote some 30 plays, a dozen of which received awards from the governments of both Canada and Alberta as well as private sponsors such as the Edmonton Journal.[61] He first became active in theatre in the 1960s, when he acted in Academy Theatre and Peterborough Theatre Guild productions in Ontario, Canada. In the late 1960s, he became a theatre and movie critic for the Peterborough Examiner; his essays on and reviews of contemporary Off-Off-Broadway productions were collected in his critique The Theatre of Protest in America.[62] His first play, written in St. John's, Newfoundland in 1969, was The School of Night, later published as the award-winning Harriott!,[63] about the occult club formed in the 1590s by Thomas Harriott, Christopher Marlowe and Sir Walter Raleigh. The School of Night and Who Has Seen the Scroll? were first produced in Ontario in 1969–70. Prometheus Rebound,[63] written for the Open Theatre in St. John's, Newfoundland in 1969, was first produced by People & Puppets Incorporated in Edmonton, Alberta in 1971. A sequel to the dramatic poems of Aeschylus and Shelley, Botting's version of the myth portrays Prometheus' punishment for granting man access to nuclear energy. During his two-year stint as playwright-in-residence for People & Puppets he produced and directed several "Happenings," writing of that movement, "Happenings abandoned the matrix of story and plot for the equally complex matrix of incident and event."[64] Botting studied drama, including dramaturgy, in 1971–72 as a minor for his Ph.D. in English Literature, and a decade later received the Master of Fine Arts in playwriting from University of Alberta. Several of his plays were produced by the drama department, including his thesis production, Whatever Happened to Saint Joanne?, exposing the tendency of fundamental Christian ministers to exploit promising members of their sects. Edmonton Journal theater critic Keith Ashwell called Saint Joanne an "incredibly imaginative play": "In dramatizing his experiences he has written a very disquieting piece, that becomes positively uncomfortable at the end."[65] Botting's most popular award-winning plays were Crux (1983), about a nude woman who steadfastly refuses to be talked down out of her tree by her materialistic husband;[66] Winston Agonistes (1984), a sequel to George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-four;[67] and Fathers, first produced in a federal penitentiary by William Head on Stage in Victoria, British Columbia in 1993. NovelistBotting wrote his first novel, the semi-autobiographical Through Freedom's Curtain, in Hong Kong in 1962.[68] There, a Canadian journalist in Hong Kong, having entered Mao's China illegally to get a story on the refugee problem, finds himself imprisoned and facing serious charges. "His eventual escape is a metaphysical flight beyond the conventions of job, security and national pride. He discovers himself, but first must learn to live with the anguish of self-realization."[69] His recent novels include Campbell's Kids (2015),[70] set in Alberta, about an amnesiac pyromaniac who has an affair with a cheating journalist;[71] and Crazy Gran (2016),[72] set in upstate New York, where in the week after 9/11 the protagonist discovers, to her peril, that her Syrian uncle helped plan the attacks on the World Trade Centre.[73][74] Professor of English Literature and Creative WritingBotting graduated with a B.A. from Trent University with a joint major in philosophy and English literature,[75] then obtained his Master of Arts degree in English from Memorial University of Newfoundland,[76] where his focus was largely on Shakespearean authorship and textual criticism, proposing that "Gulielmus Shaksper" of Stratford was virtually illiterate (as were his children), while "William Shake-speare" was the pen name of Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford and Lord Great Chamberlain of England, a polyglot with formal training in Latin and Greek and experience travelling continental Europe, especially France and Italy.[77] Botting received his PhD in English literature and Master of Fine Arts in drama (playwriting) from the University of Alberta in Edmonton, where he taught English literature at the University of Alberta and was producer and playwright-in-residence for People & Puppets Incorporated and Edmonton Summer Theatre—precursors to the Edmonton Fringe Festival. Botting's PhD dissertation was on William Golding,[78] author of Lord of the Flies.[79] From 1972 to 1986 Botting taught English and creative writing at Red Deer College, where he was at various times the college's media relations coordinator, chairman of the English department, editor-in-chief of Red Deer College Press,[80] and president of the Faculty Association. He was later remembered by college librarian and fellow thespian Paul Boultbee (who had acted in Botting's plays Crux (1983)[81] and Winston Agonistes (1984))[82] as being a "creative, rebellious faculty member."[83] Be that as it may, Botting was named "Citizen of the Year" by the Central Alberta Allied Arts Council on 5 May 1984.[84] In the 1970s, Botting was vice-president of Central Alberta Theatre, sat on the executive of the Literary Presses Group and the Canadian Publishers Association, and was founding president of the Alberta Publishers Association.[85] He taught English and creative writing at Maskwachees Cultural College in Hobbema, establishment of which he had initially proposed in the early 1970s.[86] While first setting up his law practice in Victoria in the early 1990s he taught creative writing and English literature at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. In 1985, Botting came to national attention when he warned of a threat to academic freedom after James Keegstra was fired from his job and criminally charged with spreading hatred against an identifiable group. Keegstra had been hired as an auto mechanics teacher at Eckville High School in Alberta, but after he took a university history course was deemed qualified to teach Grade 10 history, on which "the Holocaust" was on the curriculum. Keegstra used his own texts (including the notorious The Hoax of the Twentieth Century) to teach his students that the Holocaust had been exaggerated. Not only was Keegstra fired and then prosecuted, but the RCMP removed copies of the offending texts from libraries, including University of Calgary Library.[87] Botting objected to the move in a widely-recirculated letter to the Calgary Herald.[87] That letter brought Botting to the attention of Keegstra's Victoria lawyer, Doug Christie, who enlisted the "outspoken civil libertarian" as an expert witness at both the Ernst Zundel trial in Toronto and the Keegstra trial in Red Deer, Alberta. Botting had conducted a survey demonstrating that Keegstra could not get a fair trial in Red Deer because of pretrial publicity. The Alberta Court of Appeal ruled that the judge should have allowed Botting's evidence to be heard, and ordered a new trial. Later, Botting became the first recipient of the George Orwell Free Speech Award.[87] In 1986, he resigned as professor of English at Red Deer College and entered law school. He eventually articled for Christie in Victoria, from where he "signed off" on Keegstra's appeal factum to the Supreme Court of Canada, and worked on several other of Christie's most notorious cases, at the same time continuing to teach English literature and creative writing at Simon Fraser University. However, once he was called to the bar, he went to great lengths to distance himself from Christie. Lawyer Botting entered the University of Calgary Faculty of Law on a Brunet scholarship in 1987. Shortly afterwards he joined the staff of the Institute of Natural Resources Law as a legal researcher. He was elected vice-president of Victims of Law Dilemma (VOLD), an independent watchdog group designed to keep lawyers responsible and to pressure Canadian law societies to appoint lay benchers. As a first-year law student he represented Joel Slater, an American man who became stateless after renouncing US citizenship.[88] When he was in second year, the Law Society of Alberta "investigated" Botting for representing Howard Pursley, an alleged white supremacist refugee claimant who was eventually flown directly from Calgary to Texas in a form of disguised extradition later known as extraordinary rendition.[89] Botting was cleared of any wrongdoing.[90] In his third year, Botting was enlisted by Calgary lawyers Don McLeod and Noel O'Brien to assist them with research in connection with the extradition of Charles Ng—who faced the death penalty for allegedly murdering as many as 25 men, women and children in California. That year Botting also represented the first dozen Chinese students in Canada to be granted refugee status after they publicly protested China's 1989 clampdown on demonstrators in Tiananmen Square.[91] After graduating in 1990, Botting articled in Victoria for Doug Christie. Botting pioneered the use of video appearances of witnesses in jury trials before Canadian courtrooms were equipped with video machines, in one instance convincing the judge that she and the jury should move from the courthouse to a nearby hotel in Victoria, B.C. to hear the live evidence of a witness in New Brunswick.[92][93] Notable clients whom Botting has represented include Dorothy Grey-Vik, who five decades after the fact successfully sued her parents' former hired hand for repeatedly raping her, beginning when she was a prepubescent school girl, making her his "sex slave" for two years and fathering her two children (born when she was twelve and thirteen, respectively)[94]—with her parents' complacency and complicity;[95] Gerald Gervasoni, extradited to Florida to face trial for the murder of his girlfriend, whose body was found stuffed under her mother's bed;[96] Patrick Kelly, an RCMP officer convicted of first degree murder for tossing his wife off a 17th story balcony in Toronto who sued the Correctional Service of Canada for negligence for housing him at Kingston Penitentiary without regard to risk arising from his previous status as a police officer;[97] James Ernest Ponton, charged with second degree murder after shooting his victim twice in the back—who was acquitted by a jury on the basis of Botting's argument of self-defence;[98] Clifford Edwards, for whom Botting sought a moratorium on extradition from the Minister of Justice on the grounds that the Canada-US Extradition Treaty has never been ratified by Parliament;[99] Karlheinz Schreiber, a German-born Canadian entrepreneur who fought extradition from Canada for nearly a decade;[3][100] friends of Marc Emery, a cannabis policy reform activist who consented to his extradition to the United States;[101] Mark Wilson, who won his 2011 extradition appeal on the basis that the extradition judge had refused to admit important evidence;[102][103] the family of Dr. Asha Goel, an Ontario obstetrician murdered in her sleep while visiting her brother's house in Mumbai, India—the Canadian component of the investigation having been squelched by the Department of Justice;[104][105] Emmanuel Alviar, who received a one-month jail sentence for his part in the 2011 Stanley Cup Riot in Vancouver;[106][107][108][109] Sean Doak, who fought extradition to the United States for allegedly leading a drug smuggling ring while incarcerated in a federal penitentiary;[110] Brinder Rai, a Calgary man who sued his grandfather (since deceased) and other relatives for allegedly conspiring to shoot him in the back at close range with a shotgun in an "honour killing" attempt;[111][112][113] Donald Boutilier, for whom Botting successfully challenged the constitutionality of dangerous offender legislation in the British Columbia Supreme Court,[114] a challenge rejected by the B.C. Court of Appeal,[115] and subsequently appealed by Botting to the Supreme Court of Canada, which used Boutilier as a forum for substantially reforming dangerous offender law by reverting to earlier more stringent standards for designating dangerous offenders;[116] Safa Malakpour, whose indeterminate sentence as a dangerous offender for harassing his wife after the harassment escalated to kidnapping and assault was reduced to a long-term offender designation on the basis of Boutilier;[117] Kevin Patterson, who faces extradition for murder after allegedly killing his mentor with a garden shovel;[118] and Gregory Hiles, charged with attempted murder, against whom the Crown stayed charges for lack of evidence after Botting's cross-examination of several witnesses in the first three days of a scheduled three-week trial demonstrated that each witness had motive and opportunity to commit the crime.[119][120][121] Legal scholarLong a strong advocate of advanced education for practicing lawyers,[122] Botting completed his Master of Laws in 1999 and a second PhD, in law, in 2004 at the University of British Columbia,[123][124] and went on to publish a number of scholarly works on Canadian and international law.[125] He was recognized as "Canada's leading legal scholar on extradition law" by Larry Rousseau, executive vice president of the Public Service Alliance of Canada.[126] His U.S.-published Extradition between Canada and the United States,[127] cited by the Supreme Court of Canada,[128] criticized Canada's level of cooperation with the United States in international criminal matters, arguing that Canada's policy of placing international comity over individual rights had dangerously expanded executive discretion and damaged human rights protections.[129] The book received favourable reviews in the Law & Politics Book Review and the Revue québécoise de droit international.[130] Another of his works on extradition law, Canadian Extradition Law Practice, which has gone through five editions, contains broader criticisms of Canada's network of extradition treaties, in particular of the erosion of the double criminality requirement.[131] His Extradition: Individual Rights vs. International Obligations, published in Stuttgart, Germany, was released in 2010,[132] and Halbury's Laws of Canada: Extradition and Mutual Legal Assistance the following year.[133] His Wrongful Conviction in Canadian Law (2010)[134] examines Canadian commissions of inquiry into miscarriage of justice. The book's foreword was written by David Milgaard, who was convicted of a murder he did not commit and spent 23 years in prison.[135] Botting spent four years as a visiting scholar and post-doctoral fellow at University of Washington School of Law in Seattle and another year as research associate at the University of British Columbia – where he is a Paetzold Fellow – before returning to private practice in British Columbia in 2009. In April 2015 he was granted a Trent University Distinguished Alumnus lifetime achievement award for his legal scholarship and literary skills.[136] The citation noted that Botting "is recognized as one of the most prolific legal scholars in Canada, the 'go to' expert in Canada on extradition, and a writer of immense talent."[5][6][137] In 2016 and again in 2017 he was invited to join an exclusive Oxford think-tank deliberating on the future of extradition and the European arrest warrant in the wake of Brexit.[138] He proposed "a single, simple multilateral extradition treaty to replace the European arrest warrant and the thousands of variable, and mostly unworkable, bilateral treaties now in existence."[139] He called the proposed treaty the "Unified Multilateral Extradition Treaty" or UMET, and stated that half the countries of the world would already qualify to "sign on" by virtue of being signatories to current treaty arrangements. "The other half could sign onto the new UMET in due course, once they met specific minimal standards of justice, including protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms."[140] His most recent legal texts are Dangerous Offender Law[141] and Canadian Extradition Law.[142] Personal lifeBotting has four children by his first wife, Dr Heather Botting. Married in 1966, they were divorced in 1999. In 2011, Botting married Australian-Canadian speech language pathologist Virginia ("Ginny") Martin.[143] Now retired from active practise, he continues to write novels[144] and legal texts.[145][146][147] References

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||