|

Garrett Morgan

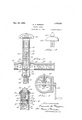

Garrett Augustus Morgan Sr. (March 4, 1877 – July 27, 1963) was an American inventor, businessman, and community leader. His most notable inventions were a type of three-way traffic light,[1] and a protective 'smoke hood'[2] notably used in a 1916 tunnel construction disaster rescue.[3][4] Morgan also discovered and developed a chemical hair-processing and straightening solution. He created a successful company called "G. A. Morgan Hair Refining Company" based on his hair product inventions along with a complete line of haircare products and became involved in the civic and political advancement of African Americans, especially in and around Cleveland, Ohio. Early life and educationMorgan was born in 1877 in Paris, Kentucky,[5][6] an almost exclusively African American community. His father was Sydney Morgan, a son and freed slave of Confederate General John H. Morgan of Morgan's Raiders.[5] His mother, also a freed slave, was Elizabeth Reed, daughter of Rev. Garrett Reed;[7] she was part Native American.[8] Garrett Morgan was the seventh of eleven children. Morgan only received a sixth grade education at Branch Elementary School in Claysville, Kentucky, then moved in search of work at the age of 14 to Cincinnati, Ohio.[5][9] CareerMorgan spent most of his teenage years working as a handyman for a Cincinnati landowner. Like many African American children growing up at the turn of the century, he had to quit school at a young age to work full-time.[10] Morgan hired a tutor and continued his studies while working in Cincinnati. In 1895, he moved to Cleveland,[5] where he began repairing sewing machines for a clothing manufacturer. This experience sparked Morgan's interest in how things worked, and he built a reputation for fixing them. His first invention, made during this period, was a belt fastener for sewing machines.[10] Morgan also invented a zigzag attachment for sewing machines.[11] In 1907, Morgan opened a sewing machine shop. One year later, more conscious of his heritage, he helped start the Cleveland Association of Colored Men in 1908.[7][12] One year later, he and his wife Mary Anne, opened Morgan's Cut Rate Ladies Clothing Store.[13] The shop made coats, suits, dresses, and other clothing, and ultimately had 32 employees.[7] Around 1910, his interest in repairing other people's inventions waned, and he became interested in developing some of his own. He received his first patent in 1912. In 1913, he incorporated hair care products into his growing list of patents and launched the G. A. Morgan Hair Refining Company, which sold hair care products, including his patented hair straightening cream, hair coloring, and a hair straightening comb invented by Morgan. He received a patent for his smoke hood design in 1914, also known as a 'breathing device'.[2] That same year, he launched the National Safety Device Company. The invention earned him the first prize at the Second International Exposition of Safety and Sanitation in New York City."[14] In 1916, Morgan rescued workers trapped in a water intake tunnel 50 ft (15 m) beneath Lake Erie, using the smoke hood to protect his eyes from smoke and featuring a series of air tubes that hung near the ground to draw clean air beneath the rising smoke.[15][16] Morgan would also design a traffic signal in 1923 after witnessing a horrible crash at an intersection. His manually-operated design included moving arms featuring signals for "go" and "stop".[1] He eventually sold the rights to General Electric for $40,000.[14] Later in life he developed glaucoma[5] and by 1943 was functionally blind. He had poor health the rest of his life,[15][17] but continued to work on his inventions. One of his last was a self-extinguishing cigarette, which used a small plastic pellet filled with water placed just before the filter. He died on July 27, 1963,[7][17][18] at age 86 and was buried at the Lake View Cemetery in Cleveland.[7][19] Products and inventionsHair care productsMorgan conducted experiments with a liquid that gave sewing machine needles a high polish that prevented the needle from burning fabric as it sewed. In 1905, Morgan accidentally discovered that the liquid could also straighten hair.[7] After he discovered this, he wiped the liquid on a piece of pony fur cloth and it stood straight. He also observed that the liquid worked on his neighbor's dog and his own hair.[20] He made the liquid into a refining cream and launched the G. A. Morgan Hair Refining Company to market it. Morgan received great success and added other products including "hair-growing" cream, black hair oil dye, and a curved-tooth comb for hair straightening in 1910.[13] Traffic signalFollowing the success of his company, Morgan became a well-known citizen in Cleveland and achieved financial success leading to his purchasing of a new automobile. In 1922, he witnessed an accident between a horse-drawn carriage and a car which sparked inspiration to prevent the likelihood of future events occurring. Morgan designed a manually-operated traffic signal with moving arms featuring "stop" and "go" signs, which could be situated on a post at traffic intersections. The arms could also be raised halfway to indicate caution moving forward. A traffic attendant would crank the post to operate the signal and all lanes could be stopped by showing "stop" if needed.[1] A patent for Morgan's traffic signal was issued in 1923 and he later sold the rights to General Electric for $40,000.[21]

Smoke hood Garrett Morgan invented a "safety hood smoke protection device" after seeing firefighters struggling to withstand the suffocating smoke they encountered in the line of duty.[8] His device used a moist sponge to filter out smoke and cool the air.[16] It took advantage of the way smoke and fumes tend to rise to higher positions while leaving a layer of more breathable air below, by using an air intake tube that dangled near the floor.[15] The hood used a series of tubes to draw clean air of the lowest level the tubes could extend to. Smoke, being hotter than the air around it, rises, and by drawing air from the ground, the Safety Hood provided the user with a way to perform emergency respiration. He filed for a patent on the device in 1912,[15][22][23] and founded a company called the National Safety Device Company in 1914 to market it. He was able to sell his invention around the country, sometimes using the tactic of hiring a white actor who would take credit rather than revealing himself as its inventor.[8] For demonstrations of the device, he sometimes adopted the disguise of "Big Chief Mason," a purported full-blooded Indian from the Walpole Island Indian Reserve in Canada.[24] He would demonstrate the device by building a noxious fire fueled by tar, sulfur, formaldehyde, and manure inside an enclosed tent.[15] Disguised as "Big Chief Mason," he would enter the tent full of black smoke, and would remain there for 20 minutes before emerging unharmed.[15] A successful demonstration was also presented in Cleveland, Ohio. A representative of the company, Mr. Mason, entered a poisonous building with Morgan's hood on his head and remained in that environment for twenty minutes. The test was satisfactory according to Chief Stickle of the Cleveland Fire Department, who said that the device was much cheaper and simpler than the oxygen mask used during that time. Following the demonstration, Chief Stickle recommended the purchase of several smoke hoods for the fire department. Mr. Mason continued to make numerous demonstrations in Ravenna, Youngstown, Canton, and other neighboring cities in Ohio where the device was proclaimed a success. The purchase of Morgan's Smoke Hood was not limited within the boundaries of fire departments in northeastern Ohio. Many large cities throughout the United States had Morgan's Smoke Hood in their fire departments, hospitals, asylums, and ammonia factories, and were using them satisfactorily. His safety hood device was simple and effective, whereas the other devices in use at the time were generally difficult to put on, excessively complex, unreliable, or ineffective.[15] It was patented[25] and awarded a gold medal two years later by the International Association of Fire Chiefs. Morgan's safety hood was used to save many lives during the period of its use.[15] He also developed later models that incorporated an airbag that could hold about 15 minutes of fresh air.[15][17] His invention became known nationally when he led a rescue that saved several men's lives after the July 24, 1916, Waterworks Tunnel explosion in Cleveland, Ohio.[15][16][26] Before Morgan arrived, two previous rescue attempts had failed. The attempted rescuers had become victims themselves by entering the tunnel and not returning. Morgan was roused in the middle of the night after one of the members of the rescue team who had seen a demonstration of his device sent a messenger to convince him to come and to bring as many of his Safety Hoods as he could.[15] He, as well as his brother Frank, arrived on the scene still wearing their pajamas and bringing four Smoke Hoods with them.[15][17][16] Most of the rescuers on the scene were initially skeptical of his device, so he and his brother went into the tunnel along with two other volunteers, and succeeded in pulling out two men from the previous rescue attempts.[15][16] He emerged carrying a victim on his back, and his brother followed just behind with another.[17] Others joined in after his team succeeded, and rescued several more.[15] His device was also used to retrieve the bodies of the rescuers that did not survive. Morgan personally made four trips into the tunnel during the rescue, and his health was affected for years afterward from the fumes he encountered there.[15] Cleveland newspapers and city officials initially ignored Morgan's act of heroism as the first to rush into the tunnel for the rescue and the key role he played as the provider of the equipment that made the rescue possible, and it took years for the city to recognize his contributions. The mayor, Harry L. Davis, failed to put Garrett Morgan's name on the list of recommended heroes.[8][15] City officials requested the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission to issue medals to several of the men involved in the rescue but excluded Morgan from their request.[15] He believed that the omission was racially motivated. Morgan's suspicions were confirmed by Victor M. Sincere of the Bailey Company in his statement to the Citizens Award Committee. "Your deed should serve to help break down the shafts of prejudice with which you struggle. And is sure to be the beacon of light for those that follow you in the battles of life."[15] Later, in 1917, a group of citizens of Cleveland tried to correct for the omission by presenting him with a diamond-studded gold medal.[15] After the heroic rescue Morgan's company received more order requests from fire departments all over the country. However, the national news contained photographs of him, and officials a number of southern cities canceled their existing orders when they discovered he was black. Morgan said in his diary, "I had but a little schooling, but I am a graduate from the school of hard knocks and cruel treatment. I have personally saved nine lives." He was also given a medal from the International Association of Fire Engineers, which made him an honorary member.[17]

Community leadershipIn 1908, he co-founded the Cleveland Association of Colored Men, which later merged with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.[7][12][17] Morgan served as its treasurer.[17] He was a member of the NAACP and donated money to historically black colleges and universities.[8] Morgan, in 1920, founded the Cleveland Call, a weekly newspaper and, in 1938, subsequently participated in its merger that created the Cleveland Call and Post newspaper.[27] Morgan purchased a farm near Wakeman, Ohio, and upon that land build the Wakeman Country Club, open to Blacks, unlike most country clubs then. Morgan was a member of the Prince Hall Freemasons, in Excelsior Lodge No. 11 of Cleveland, Ohio.[28] He belonged to Antioch Baptist Church.[5] In 1931, seeing that the city was neither properly addressing the needs of its African American citizens, he ran for a seat on the Cleveland City Council as an independent, but was not elected.[10][15] Personal lifeHe married Madge Nelson in 1896, only to divorce in 1898. In 1908, he and Czech-immigrant Mary Hasek were married.[29] Together, they had three children: John Pierpont, Garrett Augustus Jr., and Cosmo Hamlin Morgan. Garrett died in Cleveland in 1963, where he was buried in Lake View Cemetery.[30] Awards and recognitions At the Emancipation Centennial Celebration in Chicago, Illinois, in August 1963 (one month after his death), Morgan was nationally recognized.[5] In the Cleveland, Ohio, area, the Garrett A. Morgan Cleveland School of Science and the Garrett A. Morgan Water Treatment Plant are named in his honor. In 2023 the Cleveland Fire Department's new fire boat was named in his honor. In Chicago, an elementary school is named in his honor.[31] An elementary school bearing his name opened in the fall of 2016 in Lexington, Kentucky.[32] In Prince George's County, Maryland, there is a street named Garrett A. Morgan Boulevard (formerly Summerfield Boulevard until 2002) and the adjacent Metro stop (Morgan Boulevard) also bears his name. Morgan was included in the 2002 book 100 Greatest African Americans by Molefi Kete Asante.[33] Morgan is an honorary member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.[5][34] Morgan's invention of the safety hood was featured on the television show Inventions that Shook the World[35] and Mysteries at the Museum (S08E05). References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Garrett Morgan. |

||||||||||||||