|

Fritz the Cat

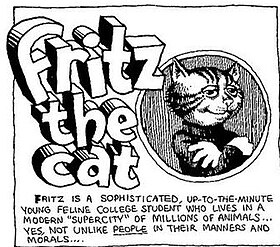

Fritz the Cat is a comic strip created by Robert Crumb. Set in a "supercity" of anthropomorphic animals, it focused on Fritz, a tabby cat who frequently went on wild adventures that sometimes involved sexual escapades. Crumb began drawing the character in homemade comic books as a child, and Fritz would become one of his best-known characters. The strip first appeared in Help! and Cavalier magazines, and subsequently in publications associated with the underground comix scene between 1965 and 1972; Fritz the Cat comic compilations elevated it to one of the underground scene's most iconic features. Fritz the Cat received further attention when it was adapted into a 1972 animated film of the same name. The directorial debut of animator Ralph Bakshi, it was the first animated feature film to receive an X rating in the United States, and the most successful independent animated feature to date. Crumb ended the strip later that year due to disagreements with the filmmakers. OverviewFritz the Cat was created in 1959 by Robert Crumb in a homemade comic book story called "Cat Life", based on the experiences of Fred, the family cat.[1][2] The character's next appearance was in a 1960 story entitled "Robin Hood". By this point, the cat had become anthropomorphic and had been renamed Fritz, a name derived from a minor unrelated character who appeared briefly in "Cat Life".[1][3] Fritz appeared in the early 1960s Animal Town strips drawn by Charles and Robert Crumb. Sometimes Fritz was accompanied by Fuzzy the Bunny, who served as an alter ego for Charles, his creator.[1] Fritz the Cat is set in a "modern 'supercity' of millions of animals."[4] Stories begin simply and become increasingly chaotic and complex as the narrative responds to uncontrollable forces.[1] The look of Fritz the Cat comics was characterized by the use of the Rapidograph technical pen and a simple drawing style Robert Crumb used to facilitate his storytelling.[5][6] Crumb states that much of the comic books he enjoyed as a child were talking animal comics, particularly those of Carl Barks.[7] Crumb was later influenced by Walt Kelly's daily anthropomorphic animal comic strip Pogo;[8] Crumb did not copy Kelly's comics directly, but states that he imitated his drawing style closely; Crumb admired Kelly's storytelling style, which "seemed [to be] plotless and casually done. The characters talked to each other and nothing much happened. Just a lot of foolishness takes place".[9] Crumb said of his anthropomorphic work:

In 1964, when he was not working at American Greetings, Crumb drew many Fritz the Cat strips for his own amusement. Some of them were later published in Help! and Cavalier magazines and in underground comix.[10] Fritz also appears briefly in Crumb's graphic novel Big Yum Yum Book: The Story of Oggie and the Beanstalk, drawn in 1964, but not published until 1975.[11] Several characters from the anthropomorphic universe of Fritz the Cat appeared in another Crumb comic strip, The Silly Pigeons, drawn in 1965 and intended for Help![12] In 1970, Crumb redrew an early Fuzzy the Bunny story written by Charles Crumb in 1952; it was published in Zap Comix #5.[7] CharactersMarty Pahls, Crumb's childhood friend, describes Fritz as "a poseur", whose posturing was taken seriously by everyone around him.[3] Fritz is self-centered and hedonistic, lacking both morals and ethics.[3] Thomas Albright describes Fritz as "a kind of updated Felix with overtones of Charlie Chaplin, Candide, and Don Quixote."[13] Fritz had a "glib, smooth and self-assured" personality, characteristics Crumb felt he himself lacked.[14] According to Pahls, "To a great extent, Fritz was his wish-fulfillment ... [the character allowed Robert to] do great deeds, have wild adventures, and undergo a variety of sex experiences, which he himself felt he couldn't. Fritz was bold, poised, had a way with the ladies—all attributes which Robert coveted, but felt he lacked."[14] Crumb denied any personal attachment to the character, stating, "I just got into drawing him ... He was fun to draw."[14] As Crumb's personal life changed, Fritz's did too. According to Pahls, "For years, [Crumb] had few friends and no sex life; he was forced to spend many hours at school or on the job, and when he came home he 'escaped' by drawing home-made comics. When he suddenly found a group of friends that would accept him for himself, as he did in Cleveland in 1964, the 'compensation' factor went out of his drawing, and this was pretty much the end of Fritz's impetus."[14] An early untitled 10-page story, drawn in 1964 and released in 1969 as part of R. Crumb's Comics and Stories (Rip Off Press), depicts Fritz as a beatnik caricature who has an incestuous tryst with his sister.[15] In "Fred, the Teen-Age Girl Pigeon," Fritz is portrayed as a pop music star.[16] The strips "Fritz the Cat" and "Fritz Bugs Out" portray him as a hip poet and college dropout in the hippie scene.[14][17] "Fritz Bugs Out" uses anthropomorphic characters to comment on race relations, with crows representing African Americans.[18] Fritz is portrayed as a self-conscious hypocrite, obsessed with his racism and associated guilt, while crows are portrayed as "hip innocents".[18] "Fritz the Cat, Secret Agent for the C.I.A.," inspired by the popularity of the James Bond series, portrays Fritz as a member of the Central Intelligence Agency.[14][17] "Fritz the No-Good" depicts him becoming involved with terrorist revolutionaries; he also abuses and rapes one of the group members’ girlfriends.[19] Fritz has an on-again/off-again relationship with a female fox named Winston; they break up at the beginning of "Fritz Bugs Out".[20] Later in the story, she attempts to convince him not to "bug out", but eventually agrees to go on a road trip with him.[21] When her car overheats and stalls in the desert, Fritz abandons her. Winston is also a character featured in the 1972 film, as is this storyline—Fritz's Volkswagen Beetle dodging big rig trucks on the highway in the middle of the night and later running out of gas in the middle of nowhere.[21] She reappears in "Fritz the Cat Doubts His Masculinity"[22] and in "Fritz the No-Good", where they reunite after Fritz is thrown out of his wife's apartment.[23] Fuzzy the Bunny, who appeared in the early Animal Town strips, reappears as a college student in "Fritz Bugs Out"[24] and as a revolutionary in "Fritz the No-Good".[25] Publication historyHelp!, a magazine published by former Mad editor Harvey Kurtzman, published two stories featuring Fritz, including the character's first public appearance in January 1965, "Fritz Comes on Strong".[26] In this debut story, Fritz brings a young female cat home and strips all her clothes off before getting on top of her to pick fleas off of her. Preceding the publication of the story, Kurtzman sent Crumb a letter which read, "Dear R. Crumb, we think the little pussycat drawings you sent us were just great. Question is, how do we print them without going to jail?"[8][27][28] Although Kurtzman agreed to publish the story, he requested that Crumb alter the final two panels; the published version depicted Fritz standing next to her.[28] Crumb later recalled that the original ending "wasn't that dirty ... only slightly risque by today's standards".[8] In May 1965, Help! published a second Fritz story, "Fred, the Teen-Age Girl Pigeon". In this episode Fritz is a guitar-playing pop idol and he brings Fred, a female pigeon groupie, to his hotel room and proceeds to eat her.[29][30] John Canaday's New York magazine review of Head Comix describes this punch line as "outrageous brilliance [that] is rivaled only by Evelyn Waugh's last lines in The Loved One."[16] "Fritz Bugs Out" was serialized in Cavalier from February to October 1968.[3] In the summer of 1968, Fritz the Cat strips appeared in the Viking Press compilation titled Head Comix, which focused exclusively on Crumb's material.[3] In 1969, Ballantine Books paid Crumb a $5,000 advance for the publication rights to a compilation of three stories featuring Fritz. Crumb used the money to purchase a three-acre lot.[17] In 2017, Crumb's original cover art for the Ballantine collection sold at auction for $717,000, the highest sale price to that point for any piece of American cartoon art.[31] Crumb abandoned the character the same year as the Ballantine collection,[10] but previously unpublished stories appeared in Promethean Enterprises No. 3 and 4 in 1971 and Artistic Comics (Golden Gate Publishing Company) in 1973.[32] "Fritz the Cat 'Superstar'" — featuring the death of the character — was the last new story released; it was published in The People's Comics (Golden Gate) in 1972.[33] In 1978, Bélier Press published The Complete Fritz the Cat, which brought together all the published stories featuring Fritz, as well as previously unpublished drawings and unfinished comics. At the artist's request, a 10-page story drawn in 1964 and previously published in R. Crumb's Comics and Stories (Rip Off Press) in 1969 was excluded from this collection.[34] In April 1993, Fantagraphics Books published The Life & Death of Fritz the Cat, compiling nine major strips, including the 1964 story previously excluded from The Complete Fritz the Cat.[35] Fritz the Cat strips also appear in The Complete Crumb Comics series.[36][37][38][39] An unpublished page featuring Fritz that had been intended for Help!, as well as comics featuring other characters related to the anthropomorphic universe of Fritz the Cat, appeared in The R. Crumb Coffee Table Art Book in 1998.[7][12][28] List of appearancesThese Fritz comics were intended for publication:

These Fritz comics were from Crumb's sketchbooks and/or were not originally intended for publication. They are presented here in approximate chronological order of creation:

Creation dates unknown:

Cultural impactFollowing the publication of the compilations Head Comix and R. Crumb's Fritz the Cat, Crumb received increased attention and Fritz the Cat became one of the most familiar features on the underground comix scene[29][42] and Crumb's most famous creation.[5] The strip's association with the 1960s counterculture is so strong that for example the 1975 song Motorcycle Mama, being a nostalgic remembrance of the 1960s, by Swedish singer-songwriter Harpo mentions Fritz the Cat among other cultural icons of the decade such as Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, Jimi Hendrix, Ravi Shankar, Easy Rider, Woodstock, Bob Dylan, and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, and according to Dez Skinn, author of Comix: The Underground Revolution, the strip served as an inspiration for Omaha the Cat Dancer.[43] Like many other of Crumb's creations, Fritz the Cat has remained not without detractors. In Graphic Novels: A Bibliographic Guide to Book-Length Comics, D. Aviva Rothschild criticized the stories printed in the collection The Life & Death of Fritz the Cat as being misogynist, racist, and violent. He felt that, "They also tend to ramble, as if Crumb were making them up as he went along."[44] Rothschild concluded that, "Even though Fritz the Cat is a classic, there are better, more coherent Crumb books around."[44] The stories served as the basis for a pair of film adaptations produced by Steve Krantz, Fritz the Cat (1972), directed by Ralph Bakshi,[45] and The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat (1974), directed by Robert Taylor. The first film adaptation of Fritz the Cat was ranked 51st on the Online Film Critics Society's list of the top 100 greatest animated films of all time[46] and 56th on Channel 4's list of the 100 Greatest Cartoons.[47] Animated adaptations In 1969, New York animator Ralph Bakshi came across a copy of R. Crumb's Fritz the Cat and suggested to producer Steve Krantz that it would work as a film.[48] After meeting with Bakshi, Crumb loaned him one of his sketchbooks as a reference,[48] but was unsure of the film's production and refused to sign the contract.[48] Bakshi and Crumb were unable to reach an agreement after two weeks of negotiations but Krantz secured the film rights from Crumb's wife, Dana, who had a power of attorney.[48] Crumb received $50,000, distributed over the course of production, and ten percent of Krantz's proceeds.[48] Fritz the Cat was the first animated feature film to receive an X rating from the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA).[49] The film's distributor capitalized on the rating in the film's advertising material, which touted the film as being "X rated and animated!"[49] Released on 12 April 1972, it opened simultaneously in Hollywood and Washington, D.C.[14] The film became a worldwide hit, grossing over $100 million (USD) and was the most successful independent animated feature ever.[48] Crumb disliked how the film presented the sexual content and politics, denouncing Fritz's dialogue in the final sequences of the film, which includes a paraphrased quote from The Beatles song "The End", as "red-neck and fascistic."[10][14][50] Nonetheless, the film is credited with extending Crumb's reputation beyond the underground comix scene.[29] Following the film's release, Crumb quickly produced the story "Fritz the Cat 'Superstar',"[51] in which he satirized Bakshi and Krantz. Crumb portrayed Fritz in a script conference for Fritz Goes to India, a fictional sequel to the film.[33][48] Crumb's story ends with a neurotic ex-girlfriend killing Fritz. She murders him by stabbing him in the back of the head with an ice pick due to Fritz's overt sexism.[33] After the film's release, the American humor magazine the National Lampoon published a comics story written by mordant humorist Michael O'Donoghue, and drawn by Randall Enos in a parody of Crumb's style, called "Fritz the Star in 'Kitty Glitter.'"[52] The four-page piece portrayed the Fritz character as a jaded and complacent Hollywood star going through the motions of celebrities of the day: appearing on talk shows, commercials, and telethons mouthing vaguely liberal platitudes, before cynically guiding the conversation over to promoting his next movie. Other comics cats make appearances, including Felix the Cat, Krazy Kat, and underground comix cats Pat (from Jay Lynch's Nard n' Pat)[53] and Kim Deitch's Waldo.[54] The strip ends with a nightmarish full-page vista of "Crumbland", where all of Crumb's countercultural icons have been turned into commercial commodities.[55] In 1974, Krantz produced a sequel, The Nine Lives of Fritz the Cat, without participation from either Bakshi or Crumb.[3][56] See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||