|

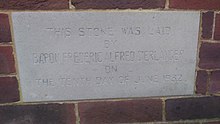

Frédéric Alfred d'Erlanger Baron Frédéric Alfred d'Erlanger (29 May 1868 – 23 April 1943[1]) was an Anglo-French composer, banker, and patron of the arts. His father, Baron Frédéric Émile d'Erlanger, was a German[2] head of a French banking house.[3] His mother, Mathilde (née Slidell),[4] was an American.[1] LifeOne of four sons,[5] d'Erlanger was born in Paris.[2] (See: Erlanger family tree). He began his musical studies in Paris under Anselm Ehmant,[1] his only teacher. His first work, a book of songs, was published when d'Erlanger was 20 years of age. Shortly afterwards, in 1886, he moved to London with his elder brother, Baron Emile Beaumont d'Erlanger, to work as a banker,[2] for the private banking firm that his father owned.[3] Both d'Erlanger and his brother became naturalised Englishmen.[3] A millionaire,[6] d'Erlanger was described as a "genuine Renaissance man"; he was a noted patron of the arts in London, promoting and financing opera at Covent Garden and acting as a trustee of the London Philharmonic Orchestra.[7] He also invested in developing countries, financing department store chains in South America and railways in South Africa.[2] He was a founding member of the Oxford and Cambridge Musical Club.[8] "Baron Fred", as he was known, was a frequent participant in the regular Thursday musical soirées of the club. The supplement to The London Gazette of 27 February 1918, in records of the partners in the firm Erlangers, records Baron Fred's home at that time as Park House, Rutland Gate, London. In 1925, d'Erlanger married Catherine, "a French woman of good family".[9]  In 1932, he put his name on the foundation stone of what was then the Musicians' House, later renamed Merebank House, in what was then fairly open countryside between Dorking and Horsham, constructed for the Musicians' Union (which he supported) as a retirement home for five musicians.[10] D’Erlanger's own home by then was at 4, Moorgate, but he actually died while staying at Claridges Hotel London, a favourite of his, on 23 April 1943, leaving £601,461 in his will. One of his two executors was his nephew, Leo Frederic Alfred d'Erlanger, son of Baron Fred's brother, the French painter Baron Rodolphe d'Erlanger. The other executor was a solicitor. MusicD'Erlanger was really an amateur "gentleman composer" whose day job as a banker helped fund his interest in music.[11] He composed operas, chamber music, and orchestral works, among other types. The operas included Jehan de Saintré[1] (Aix-les-Bains, 1 August 1893; Hamburg, 1894), Inès Menso[2] (produced, under the pseudonym of Ferd. Regnal, in London at Covent Garden on 10 July 1897, and subsequently in Germany as Die Erbe); Tess[2] (after Thomas Hardy's Tess of the d'Urbervilles[12]), produced at the Teatro di San Carlo, Naples, on 7 April 1906 and at Covent Garden on 14 July 1909, on both occasions under the baton of Ettore Panizza; and Noël, produced at the Paris Opéra-Comique on 28 December 1910. In 1935, his one-act ballet Les cents baisers ("The Hundred Kisses") with a libretto by Boris Kochno, was produced by the Ballets Russes and choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska, with decor and costumes by Jean Hugo.[13] It was subsequently recorded by Antal Dorati and the London Symphony Orchestra.[14] Orchestral works include the Suite symphonique No. 2, first performed at the Proms on 18 September 1895,[15] and the Violin Concerto in D minor, op 17 (1902), first performed by Hugo Heermann in Holland and Germany, and then taken up by Fritz Kreisler for its British premiere at the Queen's Hall on 12 March 1903.[16] There was also the Andante Symphonique Op 18 for cello and orchestra (1904), the symphonic prelude Sursum Corda! (1919) and the Concerto Symphonique for piano and orchestra (1921),[17] as well as the choral Messe de Requiem of 1930, admired and performed by Adrian Boult.[1] An orchestral waltz, Midnight Rose became popular and was recorded by John Barbirolli in 1934.[16] The chamber music includes a String Quartet and the Violin Sonata in G minor (both 1900). The Piano Quintet was first performed at St James's Hall, Piccadilly, on 1 March 1902 by the Kruse Quartet, with d'Erlanger himself as pianist.[7] Clearness of form and elegance of idea and expression are the distinguishing marks of d'Erlanger's music, whether in his operatic work, in his chamber and orchestral music, or in his songs.[1] A recent revival in interest has resulted in new recordings of his Piano Quintet (1901), Violin Concerto (1902), Andante Symphonique for cello and orchestra (1903), Concerto Symphonique for piano and orchestra (1921) and Prelude Romantique (1934), among other pieces.[18] The Birmingham Festival Choral Society revived the Messa de Requiem with a live performance in 2001.[19] Selected compositionsOpera

Ballet

Concertante works

Orchestral works

Choral works

Chamber music

Piano music

Lieder

References

External links

|