|

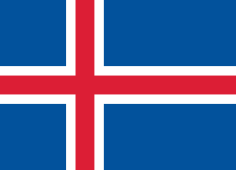

Flag of Iceland

The flag of Iceland (Icelandic: íslenski fáninn) was officially described in Law No. 34, set out on 17 June 1944, the day Iceland became a republic. The law is entitled "The Law of the National Flag of Icelanders and the State Arms" and describes the Icelandic flag as follows: The civil national flag of Icelanders is blue as the sky with a snow-white cross, and a fiery-red cross inside the white cross. The arms of the cross extend to the edge of the flag, and their combined width is 2⁄9, but the red cross 1⁄9 of the combined width of the flag. The blue areas are right angled rectangles, the rectilinear surfaces are parallel and the outer rectilinear surfaces as wide as them, but twice the length. The dimensions between the width and length are 18:25. Iceland's first national flag was a white cross on a deep blue background. It was first shown in parade in 1897. The modern flag dates from 1915, when a red cross was inserted into the white cross of the original flag. This cross historically stems from the symbol of Christianity.[2][3] It was adopted and became the national flag when Iceland was granted sovereignty by Denmark in 1918. For Icelanders, the flag's colouring represents a vision of their country's landscape. The colours stand for three of the elements that make up the island. Red is the fire produced by the island's volcanoes, white recalls the ice and snow that covers Iceland and blue represents the mountains of the island.[4] History According to a legend described in Andrew Evans' Iceland,[5] a red cloth with a white cross fell from the heavens, ensuring Danish victory at the Battle of Valdemar in the 13th century. Denmark then used the cross on its flag throughout its Nordic territories as a sign of divine right. Upon Iceland's independence, they continued to use the Christian symbol. The civil flag of Iceland had been used as an unofficial symbol since the late 19th century, originally as a white cross on a blue background. The current design was adopted on 19 June 1915, when King Kristján X issued a decree allowing it to be flown in Icelandic territorial waters, where only the Danish flag had been permitted, and stipulating that a red cross was to be incorporated into the design to distinguish it from similar foreign flags.[6] Other symbolic meanings refer to the natural features of Iceland itself. Blue is the colour of the mountains when looked at from the coast, white represents the snow and ice covering the island for most of the year, and red the volcanoes on the island.[4]

Laws regarding the flagOn 17 June 1944, the day Iceland became a republic, a law was issued that dealt with the national flag and the coat of arms. To date, this is the only major law to have been made about the flag and coat of arms, aside from two laws made in 1991: one that defines official flag days as well as the time of day the flag can be drawn, and another that defines the specific colours comprising the Icelandic flag. (The law codified what had been common custom.) The law describes the dimensions of both the common flag and special governmental flags used by embassies and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It also goes into details of usage, such as how the flag should be attached in different situations such as on a flagpole, on a house and on different kinds of ships. According to the law, using the flag is a privilege and not a right. The owner must follow instructions on its usage and make sure that his or her flag is in mint condition regarding colouring, wear and tear. It also states that no one shall disrespect the flag in act or word, subject to a fine or imprisonment of up to one year. The original law stated in its seventh article that another law would be set regarding official flag days and the time of day that the flag may be flown, but such a law was not put into effect until almost 50 years later in 1991. This law states that the flag shall not be flown until 7:00 in the morning and it should preferably not be flown beyond sunset but that it must not be flown beyond midnight. However, if the flag is raised at an outdoor assembly, an official gathering, funeral or a memorial the flag may be flown as long as the event lasts though never beyond midnight. Icelandic flag days  According to Law No. 5 of 23 January 1991, the following are nationally sanctioned flag days. On these days the flag must be raised at official buildings, and those under the supervision of officials and special representatives of the state. Any additions to the list below can be decided each year by the Prime Minister's Office. On these days, the flag must be fully drawn, except on Good Friday where it must be drawn at half-mast.

The state flag The Icelandic state flag (Ríkisfáni), known as the Tjúgufáni, was first flown on 1 December 1918 from the house of ministry offices although laws regarding its uses had not been finished. It was not until 12 February 1919 that such a law was enacted. The State flag is used on governmental buildings and embassies. It is also permitted to use the flag on other buildings, if they are being used by the government in some fashion. The Tjúgufáni is the Naval Ensign of the Icelandic Coast Guard as well, and state ships and other ships put to official uses are permitted to use it. The customs service flag is used on buildings used by the Directorate of Customs and at checkpoints, as well as by ships used by the Directorate of Customs. The Icelandic presidential flag is used on the dwellings of the President, as well as any vehicles that transports them. Colours of the flagOfficially, the colours of the Icelandic flag follow a law set in 1991, which states that the colours must be the following Standard Colour of Textile (Dictionnaire International de la Couleur) hues:

The government of Iceland has issued[7] colour specifications in the better known Pantone, CMYK, RGB, hex triplet and Avery systems.

Construction sheetsNational and merchant flag State and war flag, state and naval ensign See also

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to National flag of Iceland. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||