|

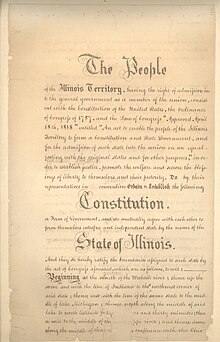

First Illinois Constitutional Convention The First Illinois Constitutional Convention was held in August 1818 as a precondition for Illinois statehood. The 33 delegates elected from Illinois' 15 counties met in a tavern in Kaskaskia, the territorial capital on the first Monday in August 1818. Before the month was out, they had produced the Illinois Constitution of 1818. The convention's work paved the way for statehood and governed the law of Illinois for the state's first 30 years. BackgroundFor several years residents of the Illinois Territory had agitated against the restrictions placed on them by the territorial system of government under the Northwest Ordinance, including the absolute veto that the appointed governor held over the elected legislature. On December 2, 1817, the territorial legislature appointed a committee to draft a "memorial to congress" seeking admission of Illinois as a state.[1] The petition was approved four days later.[2] Governor Ninian Edwards proclaimed his own strong support for the initiative.[3] On New Year's Day 1818, Edwards vetoed legislation that would have repealed the Illinois Territory's indenture laws. He then prorogued the territorial legislature to prevent any further discussion of the topic. This episode brought the issues of slavery and the veto power to the forefront of the territory's political conversation leading up to the convention.[4] Illinois territorial delegate Nathaniel Pope and his nephew, Daniel Pope Cook, who had become clerk of the US House of Representatives, shepherded the statehood bill to passage through the spring of 1818. Pope was able to obtain a number of crucial amendments, including one that extended the state's boundary far to the north into what had been the Wisconsin Territory, from the original territorial boundary at the southern tip of Lake Michigan.[5] The statehood bill, which was signed into law by President Monroe on April 18, 1818,[6] required that Illinois reach a population of at least 40,000. This was only two-thirds of the threshold for statehood set by the Northwest Ordinance, but it still proved difficult. Census takers appointed by the governor had enumerated only 34,620 people by the territory's self-imposed deadline of June 1.[7] On the theory that the population would rise later in the year, the returns were kept open, and by the convention a reported total of 40,258 was reached.[7] Historian Robert Pickrell Howard described this census as "a series of frauds", which included counting the 600 residents of Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin as residents of Illinois.[7] Election When statehood for Illinois was approved on April 18, 1818, the U.S. Congress approved the formation of a state constitution. Madison, St. Clair, and Gallatin counties were allocated three delegates each, while all other counties were allocated two delegates each.[8] The elections for delegates were held "viva voce" at each county's county seat on July 6, 7 and 8, 1818. Each voter's vote was proclaimed aloud by the county sheriff.[9] All white male U.S. citizens who had resided in the Illinois Territory for at least six months prior to the election, or whom were otherwise qualified to vote for representation, were permitted to vote.[8] Most of the election returns are not preserved, but the returns for Gallatin and Madison counties show participation of 39% and 51% respectively.[10] Members  The convention had 33 members, two from most counties and three from the three most populous counties.[11] Only 29 were present on the first day, as four of the delegates arrived a day late.[9] One, John K. Mangham, died during the convention and was not replaced.[12] All of the delegates were from the southern third of Illinois. All were white men, and despite the substantial French and Metis presence in southern Illinois, none were of French or Metis heritage.[11] Only the Irish-born Samuel Omelveny is known to have been of foreign birth, although the birthplaces of seven delegates are unknown.[13] Twenty-nine delegates had previously held some public office, whether elected or appointed.[14] Only five were lawyers.[11] Several were veterans of the Revolutionary War.[15] The average age of those delegates whose ages are known was 39. The eldest, in his late 50s, was Isham Harrison.[15] The youngest was Elias Kane, age 24. Of all the delegates, Kane was also the most thoroughly involved in all stages of the constitutional process, and made 34 of the known 134 motions.[15] Thomas Ford described him as the convention's "principal member".[16] The parchment-colored rows below represent delegates who served on the 15-member framing committee, which had one member from each county.

OfficersThe convention elected the following officers on August 3:[19]

Greenup and Owen were not delegates. They had previously served the territorial legislature in their respective roles as clerk[20] and doorkeeper.[19] CommitteesThe journal of the proceedings of the convention reflects that the following committees were formed:

Proceedings The convention met in Bennett's tavern, which was Kaskaskia's only tavern. Public interest was high. John Mason Peck, who passed through Kaskaskia during the convention, reported that "every room" in the tavern was occupied, and "every bed had two or more lodgers."[26] On the first day, officers were selected. The following day, a committee was formed to review the returns of the territorial census. On Wednesday, they reported that the total was 40,258, exceeding the 40,000 required by Congress. (The number was so inflated that it was greater than the amount found by the federal census in 1820, and included even some residents of Wisconsin.)[9] A committee of fifteen members was then formed to frame a constitution. The committee had fifteen members, one from each county. Seven were slaveholders and seven were not; one member's status is unknown.[27] Robert Blackwell and Elijah C. Berry of the Illinois Intelligencer were given the responsibility of printing the journal of the convention. Five hundred copies of the journal of the proceedings of the convention were ordered printed, but only one is known to have survived. This sole remaining copy is missing the last few pages, so the details of the proceedings for the final days of the convention are unknown.[28] Delegate John K. Mangham died on August 11. On the 12th, the framing committee presented its draft of the constitution. From the 13th through the 15th, the draft constitution was read aloud and minor changes were made. It was re-read on the 17th; up to this point, there had been little debate.[29] The draft constitution drew from the constitutions of a number of neighboring states; the strongest contributions came from Ohio and Indiana, with substantial contributions from Kentucky and Tennessee as well.[12] Certain provisions such as the veto system involving a Council of Revision, were borrowed from the New York state constitution, likely reflecting Elias Kane's influence.[30][12] On August 18, the convention discussed the matter of slavery, which was widespread in the Illinois Territory. The majority of delegates sought a compromise between the pro-slavery group and the abolitionists. Three votes were held on the matter over the remainder of the convention. Slavery was outlawed throughout most of the state, but was permitted for the Illinois Salines near Shawneetown. Furthermore, any slave currently in the state would remain a slave, though their children would become free upon reaching adulthood. This "Illinois compromise" drew the support of many pro-slavery delegates without antagonizing too many of the anti-slavery delegates.[31] Two votes were held on the seat of government, and two votes were held on the question of suffrage. The sites considered for the capital included Kaskaskia, Covington, Pope's Bluff, Hill's Ferry, and Vandalia.[32] The delegates, many of whom had personal interests in the proposed sites, were unable to reach agreement.[33] Ultimately the convention agreed to keep the capital at Kaskaskia until the General Assembly selected a new location, and that the location then chosen by the General Assembly would remain the capital for 20 years.[28] At the conclusion of the convention on August 26, 1818, the first Illinois Constitution was adopted and submitted to the United States Congress for approval.[34] Aftermath Unlike subsequent Illinois constitutions, the 1818 constitution was adopted by the convention on its own authority and was not put to popular vote. As a result of the successful completion of a constitution acceptable to Congress, Illinois was admitted to the union on December 3, 1818. Despite an unsuccessful attempt by pro-slavery politicians to organize a second constitutional convention in 1824, the 1818 constitution stood for 30 years until it was replaced by the 1848 Illinois Constitution. The 1818 constitution's provisions governing the state capital, which was to stand at Kaskaskia until the General Assembly was able to locate a more suitable location, where the capital would remain for 20 years, were followed: after a few months at Kaskaskia, the capital was moved to Vandalia in 1819 and to Springfield in 1839.[35] References

External links

|