|

Fiddler's Ferry power station

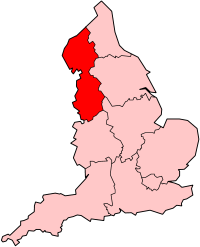

Fiddler's Ferry power station is a decommissioned coal fired power station in the Borough of Warrington, Cheshire, England. Opened in 1971,[2] the station had a generating capacity of 1,989 megawatts and took water from the River Mersey. After privatisation in 1990, the station was operated by various companies, and from 2004 to 2022 by SSE Thermal. The power station closed on 31 March 2020. The site was acquired by Peel NRE in July 2022. With four of its original eight 114-metre (374 ft) high cooling towers still standing and its 200-metre (660 ft) high chimney,[3] the station is a prominent local landmark and can be seen from as far away as the Peak District and the Pennines. The power station's four northernmost cooling towers were demolished on 3 December 2023, with the remaining four southernmost towers set to be demolished at a later date. HistoryOne of the Hinton Heavies, an application to build Fiddler's Ferry power station was proposed in 1962.[4] The civil works were built by Taylor Woodrow Construction, the cooling towers by Yorkshire Hennibique, the chimney by Tileman and the steelwork for the main buildings by the Cleveland Bridge Company between 1964 and 1971, and came into full operation in 1973.[4][1][5] There were eight cooling towers arranged in two groups of four located to the north and south of the main building. There is a single chimney located to the east of the main building.[6] One of the station's cooling towers collapsed in high winds on 13 January 1984 and was rebuilt.[4] When it was built, the station mainly burned coal mined in the South Yorkshire Coalfield and transported across the Pennines on the Manchester–Sheffield–Wath electric railway.[7] In later years, the coal was imported.[citation needed] Between 2006 and 2008, Fiddler's Ferry was fitted with a Flue Gas Desulphurisation (FGD) plant to reduce the emissions of sulphur by 94%, meeting the European Large Combustion Plant Directive.[8][9] In 2010, the station was being considered for the installation of selective catalytic reduction (SCR) equipment. This would reduce the station's emissions of nitrogen oxides, to meet the requirements of the Industrial Emissions (Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control) Directive. The SCR technology would replace the Separated Over Fire Air (SOFA) technology which was used in the station.[10] The SCR equipment was ultimately not fitted, due to uncertainty over the future of the plant.[11] The station was built by the Central Electricity Generating Board but was transferred to Powergen after privatisation of the UK's electricity industry in 1990. Fiddler's Ferry, along with the Ferrybridge power stations in Yorkshire, was then sold to Edison Mission Energy in 1999. They were subsequently sold on to AEP Energy Services in 2001, and both were sold again in July 2004 to SSE Thermal for £136 million. Between 2001 and 2011 the station was featured in the opening and closing titles and was in some background scenes of the BBC comedy series Two Pints of Lager and a Packet of Crisps. In operation The station generated electricity using four 500 MW generating sets and consumed 195 million litres of water daily from the River Mersey.[10][3] At full capacity, 16,000 tonnes of coal were burned each day.[3] It also burned biofuels together with the coal. It used SOFA technology to control nitrogen oxide emissions and FGD to reduce the emission of sulphur.[10] The station was supplied with coal via a freight-only rail line between Warrington and Widnes, running along the banks of the River Mersey. Rail facilities include an east-facing junction on the mainline controlled by a signal box, two hopper approach tracks, gross-weight and tare-weight weighbridges, coal track hoppers, a fly ash siding, a gypsum loading plant and a control building.[12] ClosureOn 18 November 2015, Amber Rudd, the then Minister in charge of the Department of Energy and Climate Change, proposed that the UK's remaining coal-fired power stations will be shut by 2025 with their use restricted by 2023. SSE announced in February 2016 that it intended to close three of the four generating units at the plant by 1 April 2016. However, it secured a 12-month contract in April 2016 and they stayed open.[13] In March 2017, the power station secured a further short-term contract to provide electricity until September 2018. At this point, the power station employed 160 people, down from 213 the previous year.[14] In February 2018, the station had agreements to supply electricity until September 2019.[15] One unit closed in 2019, reducing capacity to 1.51 GW.[16] In June 2019, SSE announced that the power station would be permanently turned off and decommissioned by 31 March 2020.[17][18] On 31 March 2020, the plant was desynchronized from the National Grid, ending nearly 50 years of electricity generation.[19] Demolition of the station was due to begin in 2020 and was forecast to take up to seven years. The land upon which it sits will be redeveloped, with Warrington Borough Council stating it had designated the land as an employment site.[20] In September 2020, the operator SSE was fined £2 million by energy regulator the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets, after it concluded that SSE did not inform energy traders that it had secured a new contract to remain open in March 2016, and had risked undermining confidence in the energy market.[21] Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, work on the site did not go ahead in 2020. Cable theftsIn December 2020, Cheshire Constabulary issued a press release stating that the site was "unsafe for intruders" and that it was still connected to the National Grid, leaving many of the cables electrically live. They stated concerns over reports that individuals had been breaking into the site.[22] In June 2021, a man was arrested for going equipped to steal and theft, after police officers found him in the power station grounds with tools and a large quantity of cable.[23] Police stated that the man was "lucky to be alive".[24] Attempted listingIn 2021, a local architect requested that Historic England consider listing the power station's cooling towers.[25] However, Historic England declined to list the towers and gave the site a certificate of immunity.[26] In response to this decision, The Twentieth Century Society expressed their concern that the demolition of this and other power stations from this generation meant that England is "at risk of losing an entire building typology that provides important landmarks and monuments to C20 industry."[27] DemolitionOn 3 December 2023, despite heavy fog partially obscuring the safety zones, the first phase of the site's demolition commenced with the four northernmost cooling towers. Local resident Grace Taylor was given the opportunity to press the detonation button after winning a raffle organised in conjunction with Peel NRE, and the four cooling towers fell in a controlled explosion at 09:35am which could be heard up to 15 miles (24 km) away, including at the Trafford Centre in Urmston, Greater Manchester. The demolition process will eventually include the remaining four cooling towers, boiler house, chimney stack and administration buildings, as well as clearance of the former coal stockyard and machinery. Phase two of the demolition is planned to take place over 18 months beginning in the first half of 2024 though the remaining four cooling towers, main power station chimney stack and the gas turbine building exhaust stack will not be demolished during this phase.[28] The site will be cleared to become housing in the near future.[29] See alsoReferences

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Fiddlers Ferry Power Station. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||