|

Fatima bint al-Ahmar

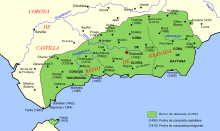

Fatima bint Muhammad bint al-Ahmar (Arabic: فاطمة بنت الأحمر) (c. 1260 – 26 February, 1349) was a Nasrid princess of the Emirate of Granada, the last Muslim state on the Iberian Peninsula. A daughter of Sultan Muhammad II and an expert in the study of barnamaj (biobibliographies of Islamic scholars), she married her father's cousin and trusted ally, Abu Said Faraj. Their son Ismail I became sultan after deposing her half-brother, Nasr. She was involved in the government of her son but was especially politically active during the rule of her grandsons, Muhammad IV and Yusuf I, both of whom ascended the throne at a young age and were placed under her tutelage. Later Granadan historian Ibn al-Khatib wrote an elegy for her death stating that "She was alone, surpassing the women of her time / like the Night of Power surpasses all the other nights". Modern historian María Jesús Rubiera Mata compared her role to that of María de Molina, her contemporary who became regent to Castilian kings. Professor Brian A. Catlos attributed the survival of the dynasty, and eventual success, as being partly due to her "vision and constancy." Background The Emirate of Granada was the last Muslim state on the Iberian Peninsula, founded by Fatima's grandfather, Muhammad I, in the 1230s. Throughout its existence, it was ruled by the Nasrid dynasty (banū Naṣr or banū al-Aḥmar).[1] Through a combination of diplomatic and military manoeuvres, the emirate succeeded in maintaining its independence, despite being surrounded by two larger neighbours, the Christian Crown of Castile to the north and the Muslim Marinid Sultanate in Morocco. Granada intermittently entered into alliance or went to war with both of these powers, or encouraged them to fight one another, in order to avoid being dominated by either.[2] For the most part, historical records do not show that women openly participated in the politics of the Emirate.[3] The Granadan poet, historian, and influential statesman Ibn al-Khatib (1313—1374), who was well acquainted with many royal women and from whom much of historical information about Fatima came from,[4] wrote in his political treatise Maqama fi al-Siyasa that women should not be put in charge of state affairs, and that their role should be limited as "the soil where one plants one's children, the myrtles of the spirit, and where the heart rests'". In practice, women sometimes did take part in political activities, especially behind the scenes. Due to frequent premature deaths of Sultans by assassinations or in battle, and the occasional accessions of underage Sultans, women at times were responsible for the interests of their families, the hereditary rights of their descendants, and diplomacy with neighbouring kingdoms.[5] Biography Early lifeFatima was born in 659 AH (1260 or 1261) during the reign of her grandfather, Muhammad I. Her father, the future Muhammad II, was heir to the throne, and her mother, Nuzha, was a first cousin of his father.[6][7] She had a brother, the future Muhammad III (b. 1257[8]) and a half-brother, Nasr, whose mother was the second wife of his father, a Christian named Shams al-Duha.[9] Her father Muhammad was known as al-Faqih (a faqīh is an Islamic jurist), due to his erudition, education, and preference for learned men such as physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and poets.[6][10] He fostered intellectual activities in his children. Fatima became expert in the study of barnamaj, the biobibliographies of Islamic scholars, while her brothers, Muhammad and Nasr, studied poetry and astronomy respectively.[6] Like her brothers, she likely received her education privately in the royal palace complex, the Alhambra.[10] Marriage to Abu Said FarajHer father Muhammad II took the throne in 1273 after the death of Muhammad I. He married Fatima to Abu Said Faraj ibn Ismail, his Nasrid cousin and influential advisor. Abu Said (born 1248) was the son of Ismail (d. 1257), Muhammad I's brother and the governor of Málaga. When Ismail died, Muhammad I brought the young Faraj to court where he befriended Muhammad II.[11] The date of this marriage appears in the anonymous work al-Dahira al-Saniyya as the year 664 AH (1265/1266, before Muhammad II's accession), but modern historian María Jesús Rubiera Mata doubts the accuracy of this date: Fatima would have been a child then, additionally the text confuses the bride as Muhammad I's daughter (while Fatima was his granddaughter), and says that the groom was his cousin (Abu Said was Muhammad I's nephew). Rubiera Mata suggests that the correct marriage date was closer to the birth of the couple's first child, Ismail, on 3 March 1279.[12] In 1279, after reoccupying Málaga, which had previously rebelled under the Banu Ashqilula, Muhammad II appointed Abu Said as the city's governor, a post once held by his father Ismail.[13][14] Abu Said left for Málaga on 11 February, while Fatima likely stayed in the Alhambra given that she was very late into her pregnancy.[15] Later, Fatima moved to Málaga, caring for her children and studying barnamaj.[16] She had a younger son, named Muhammad (unknown birth date), who had at least four sons: Yusuf, Faraj, Muhammad, and Ismail, all of whom later left the Emirate for North Africa.[17][18] Reigns of Muhammad III and NasrMuhammad III took the throne after his father's death in 1302; Fatima appeared to maintain a good relation with her brother and her husband remained the governor of Málaga throughout his reign.[19] Muhammad III was deposed in 1309 by a palace revolution in Granada, and replaced by Nasr.[16] Unlike with Muhammad III, Fatima and her husband had poor relations with her half-brother.[19][9] As his rule grew unpopular, she allied herself with factions seeking to overthrow him.[9] Her husband Abu Said led a rebellion in 1311, seeking to enthrone their children Ismail.[20][21] The rebellion was declared in the name of Ismail, because as Fatima's son he was a grandson of Muhammad II and was therefore seen as having better legitimacy than his father.[21] Their forces defeated that of the Sultan in battle, but Nasr managed to retreat to Granada despite the loss of his horse.[20] Abu Said besieged the capital but lacked supplies for a protracted campaign. Upon discovering that Nasr had allied himself with Ferdinand IV of Castile, Abu Said sought peace with the sultan and was able to retain his post as governor of Granada but paid tribute to Nasr.[20] Fearing the sultan's vengeance, Abu Said negotiated a deal with the Marinids, in which he were to yield Málaga in exchange for the governorship of Salé in North Africa. When this became known to the people of Málaga, they considered it treachery, rose up and deposed him in favor of Ismail.[22] Later, Ismail imprisoned Abu Said in Cártama after suspicions of attempting to flee Málaga, and later moved him to Salobreña where he died in 1320.[23] With her son in control of the city, Fatima helped him engineer another rebellion against Nasr,[9] enlisting the aid of Abu Said's old ally, Uthman ibn Abi al-Ula, the chief of the Volunteers of the Faith, and various factions within the capital.[9] Ismail's army swelled as he marched towards Granada, and the capital inhabitants opened the city gates for him.[23] Nasr, surrounded in the Alhambra, agreed to abdicate and retired to Guadix.[23] Ismail took the throne in February 1314 and Fatima entered court as queen mother.[24] Despite the falling out between her son and her husband, Fatima maintained good relations with her son, and appeared in various points of Ibn al-Khatib's biography of the Sultan. She assisted Ismail in political matters, in which according to Rubiera Mata she was "as gifted with great qualities as her husband."[25] When Ismail was fatally attacked by a relative in 1325, it was to her palace he was brought before he succumbed to his injuries.[26] "The Sultan's Grandmother"By the time of Ismail's death, Fatima was a highly influential figure at court and she helped secure the ascension of her grandson Muhammad IV, son of Ismail.[27] As Muhammad was only ten years old, Fatima, and a guardian named Abu Nuaym Ridwan, served as tutor and a sort of regent for the young sultan,[28] and they took active role in government.[27][29] Ibn al-Khatib referred to her during this period as jaddat al-sultan (The Sultan's Grandmother"), and according to historian Bárbara Boloix Gallardo, this was the peak period of Fatima's political activity.[30] The assassination of the vizier Ibn al-Mahruq, on the order of Muhammad IV in 1328, occurred while he was in the palace of Fatima discussing the emirate's affairs as he regularly did.[29][31] Boloix Gallardo speculated that she might have been involved in planning or masterminding this assassination.[32] Muhammad IV was assassinated in 1333 and replaced by his 15-year-old brother Yusuf I.[33] Fatima again became tutor and regent for her grandson, who was considered a minor and whose authority was limited to only "choosing the food to eat from his table".[34] According to Rubiera Mata, Fatima likely influenced Yusuf I's constructions in the Alhambra, the royal palace and fortress complex of Granada, but Boloix Gallardo argues that there is no evidence for this.[28][35] She died on 26 February 1349 (7 Dhu al-Hijjah 749 AH), during Yusuf I's reign, at the age of more than 90 years in the Islamic (lunar) calendar, and was buried in the royal cemetery (rawda) of the Alhambra.[7][28] Aftermath and legacyThe poet, historian, and statesman Ibn al-Khatib wrote a 41-verse elegy for her death, the only one ever dedicated to a Nasrid princess.[7][36] In the elegy, he wrote that "She was alone, surpassing the women of her time / like the Night of Power surpasses all the other nights".[36] He also praised her as:

After her death, the rule of Granada continued under Yusuf I, who was later succeeded by his son Muhammad V. Under their stewardship, Granada would experience its peak.[37] Historian Brian A. Catlos attributed the dynasty's eventual success partly due to Fatima's "vision and constancy", especially during the turbulent reign of her brothers, son, and grandsons, which were marred by assassinations and the reigns of young monarchs.[37] Thanks to her lineage, Ismail and his descendants gained legitimacy even though they were not male-line descendants of Muhammad I.[13] Ismail's accession was the first instance of the throne passing to a ruler through the maternal line, which would happen again in 1432 with the accession of Yusuf IV. The rule of Fatima's descendants also started what historians call al-dawla al-isma'iliyya al-nasriyya, "the Nasrid dynasty of Ismail", a distinct branch of the dynasty from that of the previous Sultans.[25] Historian María Jesús Rubiera Mata compared her guardianship and tutelage of her grandsons to those of the contemporary María de Molina, who also played a central political role as regent of her son Ferdinand IV (1295–c. 1301) and grandson Alfonso XI of Castile (1312–1321).[28] In fictionFatima bint al-Ahmar is the protagonist of the Sultana series of historical novels by Lisa Yarde.[38][39] Family tree

ReferencesFootnotes

Bibliography

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||