|

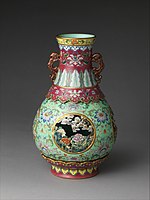

Famille rose Famille rose (French for "pink family") is a type of Chinese porcelain introduced in the 18th century and defined by pink overglaze enamel. It is a Western classification for Qing dynasty porcelain known in Chinese by various terms: fencai, ruancai, yangcai, and falangcai.[1] The colour palette is thought to have been brought to China during the reign of Kangxi (1654–1722) by Western Jesuits who worked at the palace, but perfected only in the Yongzheng era when the finest pieces were made, and famille rose ware reached the peak of its technical excellence during the Qianlong period.[2] Although famille rose is named after its pink-coloured enamel, the colour may actually range from pale pink to deep ruby. Apart from pink, a range of other soft colour palettes are also used in famille rose. The gradation of colours was produced by mixing coloured enamels with 'glassy white' (玻璃白, boli bai), an opaque white enamel (lead arsenate). Its range of colour was further extended by mixing different colours.[3][4] Famille rose was popular in the 18th and 19th century, and it continued to be made in the 20th century. Large quantities of famille rose porcelain were exported to Europe, United States and other countries, and many of these export wares were Jingdezhen porcelain decorated in Canton, and are known as "Canton famille rose". Porcelains with famille rose palette were also produced in European factories. Terms The term famille rose meaning "pink family" was introduced together with famille verte ("green family") in 1862 by Albert Jacquemart to classify Qing dynasty porcelain by their colour palettes. This is still the term most commonly used, although various other terms originating from Chinese are also used. Recent Chinese sources may use these terms in the following manner:[5]

Origin  The origin of famille rose is not entirely clear. It is believed that this colour palette was introduced to the Imperial court in China by Jesuits, achieved through the use of purple of Cassius, initially on enamels used on metal wares such as cloisonné produced in the falang or enamel workshop (珐琅作), or through adaptation of enamels used in tin-glazed South German earthenware.[1] The term used by Tang Ying (who oversaw the production of porcelain at Jingdezhen) and in Qing documents was yangcai ("foreign colours"), indicating its foreign origin or influence.[10][8] Research, however, has failed to show that the chemical composition of the pink enamel pigment on famille rose to be the same as that of the European one, although the cobalt blue of the enamel from some famille rose pieces has been determined to be from Europe.[11] The oil used in gold-red Chinese enamel was doermendina oil instead of turpentine oil used in the West.[12] Colloidal gold may have been previously available for use in Jingdezhen to achieve such colours, and gold-red enamel technique from Guangdong was used during the reign of Kangxi. Rudimentary famille rose have been found in Chinese porcelain from the 1720s, although the technique was not fully developed until around 1730 during the Yongzheng period. The pink of the early pieces of the 1720s were darker in colours made with ruby-coloured glass, but after 1725 softer shades were achieved by mixing with white enamels.[13][14] At the Palace workshops in Beijing, experimentation was conducted under the supervision of Prince Yi to develop a range of enamel colours and techniques for applying such enamels onto blank porcelain supplied by Jingdezhen. These blank porcelain would not have been produced at the Palace due to the polluting nature of the big kilns, and pieces of porcelain decorated at the palace and then fired in muffle kilns are called falangcai. Court painters were employed to make drafts that may include calligraphy and poetry to decorate such wares, which produced a new aesthetic style of decoration on porcelain distinct from those used outside the court.[5][15] Falangcai decorations may be painted on a white ground, or on a coloured ground with yellow the most popular. As falangcai was produced at the palace for its exclusive use, there are relatively fewer pieces of falangcai porcelain. Production at Jindezhen Falangcai porcelain was also made at the imperial kilns of Jingdezhen, and the term yangcai was used to refer to famille rose porcelain produced at Jingdezhen initially to imitate falangcai. Experimentations however were also conducted in Jindezhen to achieve the famille rose palette. Under the supervision of Tang Ying, production of famille rose reached the peak of its technical excellence during the Qianlong era.[2] The famille rose enamels allowed for a greater range of colour and tone than was previously possible, enabling the depiction of more complex images, and decorations became more elaborate and crowded in the later Qianlong period. The images may be painted on coloured grounds, including yellow, blue, pink, coral red, light green, 'cafe au lait' and brown.[9] Black ground or famille noire may also be used on famille rose ware, but they are not highly regarded. Many produced in the Qianlong period were on eggshell porcelain. Famille rose supplanted famille verte in popularity, and its production overtook blue and white porcelain in the mid-18th century. It remained popular throughout the 18th and 19th centuries and continued to be made in the 20th century. The quality of wares produced however declined after the Qianlong period. Export ware A large quantity of famille rose porcelain was exported, with the result that the most commonly found examples of famille rose are export ware. Sometimes they are made as sets of armorial ware specifically ordered by Europeans, Jingdezhen produced many famille rose pieces, including some of the finest pieces. However, from around 1800 onwards, many pieces were decorated in the port city of Canton to produce the Canton ware intended for export, using white porcelain from Jingdezhen. In contrast to the more refined 'court-taste' porcelain, export wares particularly those from the 19th century tend to be highly decorated. These export wares are usually decorated in Chinese style with Chinese scenes and figures, and are available in a variety of forms; for example, they may be vessels with animal-shaped covers.  Many decorative patterns are used in famille rose porcelain, sometimes with decorations requested by the buyers. Some popular types of decorative patterns in these export wares have been given specific names: Rose Canton, Rose Mandarin and Rose Medallion.[16] Rose Medallion is the most popular type of famille rose porcelain.[17] Rose Medallion typically has panels or medallion of flowers and/or bird alternating with panels of human figures around a central medallion. Rose Canton contains no human figures, in contrast to Rose Mandarin which shows Chinese figures.[18] Most of these famille rose pieces are from the 19th century; the older famille rose pieces tend to be heavier, have a grayer glaze and a more subtle pink. Famille rose porcelain from the 18th century can have a green tint, a brown rim, and may be pitted with many pinholes.[17] Famille rose enamels were known to have been used in Europe before such wares were exported from China, for example in Vienna porcelain made by the Du Paquier factory in 1725.[1] Large number of famille rose porcelains were later exported from China to the West, and many European factories such as Meissen, Chelsea and Chantilly copied the famille rose palette used in Chinese porcelain.[19] Export of Chinese porcelain then declined due to competition from the European factories. Gallery

References

External links

|