|

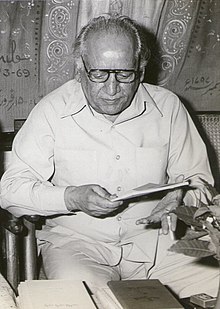

Faiz Ahmad Faiz

Faiz Ahmad Faiz[a] MBE NI (13 February 1911 – 20 November 1984)[2] was a Pakistani poet and author of Punjabi and Urdu literature. Faiz was one of the most celebrated, popular, and influential Urdu writers of his time, and his works and ideas remain widely influential in Pakistan and beyond.[3] Outside of literature, he has been described as "a man of wide experience", having worked as a teacher, military officer, journalist, trade unionist, and broadcaster.[4] Born in Faiz Nagar, British Punjab (now in Narowal District, Pakistan), Faiz studied at Government College and Oriental College[5] in Lahore[5] and went on to serve in the British Indian Army. After the Partition of India, Faiz served as editor-in-chief of two major newspapers — the English language daily Pakistan Times and the Urdu daily Imroze.[6][7] He was also a leading member of the Communist Party before his arrest and imprisonment in 1951 for his alleged part in a conspiracy to overthrow the Liaquat administration and replace it with a left-wing, pro-Soviet government.[8] Faiz was released after four years in prison and spent time in Moscow and London, becoming a notable member of the Progressive Writers' Movement. After the downfall of military dictator Ayub Khan's government, and the Independence of Bangladesh, he worked as an aide to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, but exiled himself to Beirut after Bhutto's execution at the hands of another military dictator Zia ul-Haq.[8] Faiz was a well-known Marxist and is said to have been "a progressive who remained faithful to Marxism."[9] Critics have noted that Faiz took the tenets of Marxism where Muhammad Iqbal had left it, and relayed it to a younger generation of Muslims who were considered more open to change, more receptive to egalitarianism, and had a greater concern for the poor.[10] Literary critic Fateh Muhammad Malik argues that while initially Faiz was more of a secular Marxist he eventually subscribed to Islamic socialism as his life progressed, as his poems getting more religious in tone over the years demonstrate, even suggesting that Faiz ultimately aimed for an Islamic revolution, having endorsed the 1979 Iranian revolution.[11] Faiz was the first Asian poet to be awarded the Lenin Peace Prize (1962)[12] by the Soviet Union and was also nominated for the Nobel Prize in literature.[13] He was posthumously honoured when the Pakistan Government conferred upon him the nation's highest civil award — the Nishan-e-Imtiaz — in 1990.[13][14] Early lifeFamily backgroundFaiz Ahmad Faiz was born on 13 February, 1911[15] in Kala Qader,[16] in the Sialkot District of the Punjab Province of British India (present-day Faiz Nagar,[15] in the Narowal District of Punjab, Pakistan)[17][18] into a Punjabi family.[15] Faiz's family were farmers belonging to the Tataley clan of Muslim Jutts, who were bestowed upon the Chaudhry title.[15] Faiz hailed from an academic family that was well known in literary circles. His home was often the scene of a gathering of local poets and writers who met to promote the literacy movement in his native province.[18] Faiz's father, Sultan Muhammad Khan, was a prominent barrister[17][19] who worked for the British Government and an autodidact who wrote and published the biography of Amir Abdur Rahman, an Emir of Imperial Afghanistan.[18] Khan was the son of a peasant whose ancestors migrated from Afghanistan to British India.[2] Khan worked as a shepherd as a child but was ultimately able to study law at Cambridge University.[2] EducationFollowing the Muslim tradition, Faiz's family directed him to study Islamic studies at the local mosque to be oriented to the basics of religious studies by the Ahl-i Hadith scholar Muhammad Ibrahim Mir Sialkoti.[20] Following the Muslim tradition, he learned Arabic, Persian, Urdu, and the Quran.[17][18] Faiz was also a Pakistan nationalist, and often said, "purify your hearts, so you can save the country..."[17] His father later pulled him from Islamic school because Faiz, who went to a madrasa for a few days found that the impoverished children there, were not comfortable having him around and ridiculed him. Faiz came to the madrasa in neat clothes, in a horse-drawn carriage, while the students of the school were from very poor backgrounds and used to sit on the floor on straw mats.[21] Faiz's close friend, Dr. Ayub Mirza, recalls that Faiz came home and told his father he was not going to attend the madrasa anymore. His father then registered him at the Scotch Mission School which was managed and run by a local British family. Faiz attended Murray College at Sialkot for intermediate studies (11th and 12th grade).[18] In 1926, Faiz enrolled in Department of Languages and Fine Arts of the Government College, Lahore. While there, he was greatly influenced by Shams-ul-Ulema, Professor Mir Hassan who taught Arabic and Professor Pitras Bukhari .[18] Professor Hasan had also taught Dr. Muhammad Iqbal, a philosopher, poet, and politician of South Asia. In 1926, Faiz attained his BA with Honors in Arabic, under the supervision of Professor Mir Hassan. In 1930, Faiz joined the post-graduate program of the Government College, obtaining an MA in English literature in 1932, and wrote his master's thesis on the poetry of Robert Browning.[2] The same year, Faiz completed a first-class degree at Punjab University's Oriental College.[18] It was during his college years that he met M. N. Roy and Muzaffar Ahmed who influenced him to become a member of the Communist Party.[17] In addition to Urdu, English, and Arabic, Faiz was also fluent in French and Persian.[22] CareerAcademiaIn 1935 Faiz joined the faculty of Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh, serving as a lecturer in English and British literature.[18][23] Later in 1937, Faiz moved to Lahore to reunite with his family after accepting the professorship at the Hailey College of Commerce, initially teaching introductory courses on economics and commerce.[18] In 1936, Faiz joined a literary movement, (PWM) and was appointed its first secretary by his fellow Marxist Sajjad Zaheer.[17] In East and West-Pakistan, the movement gained considerable support in civil society.[17] In 1938, he became editor-in-chief of the monthly Urdu magazine "Adab-e-Latif (lit. Belles Letters) until 1946.[17] In 1941, Faiz published his first literary book "Naqsh-e-Faryadi" (lit. Imprints) and joined the Pakistan Arts Council (PAC) in 1947.[17] Faiz was a good friend of Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko who once said "In Faiz's autobiography... is his poetry, the rest is just a footnote".[24] During his lifetime, Faiz published eight books and received accolades for his works.[24] Faiz was a humanist, a lyrical poet, whose popularity reached neighbouring India and Soviet Union.[25][self-published source] Indian biographer Amaresh Datta, compared Faiz as "equal esteem in both East and West".[25] Throughout his life, his revolutionary poetry addressed the tyranny of military dictatorships, tyranny, and oppression. Faiz himself never compromised on his principles despite being threatened by the right-wing parties in Pakistan.[25] Faiz's writings are comparatively new verse form in Urdu poetry based on Western models.[25] Faiz was influenced by the works of Allama Iqbal and Mirza Ghalib, assimilating modern Urdu with classical.[24] Faiz used more and more demands for the development of socialism in the country, finding socialism the only solution of country's problems.[25] During his life, Faiz was concerned with more broader socialists ideas, using Urdu poetry for the cause and expansion of socialism in the country.[25] Urdu poetry and ghazals influenced Faiz to continue his political themes as non-violent and peaceful, opposing the far right politics in Pakistan.[25] Faiz consistently faced political persecution for his revolutionary views and ideologies[26] and was especially targeted by the religious and conservative press due to his lifelong advocacy for the rights of women and workers.[6] Military serviceOn 11 May 1942, Faiz was commissioned in the British Indian Army as a second lieutenant in the 18th Royal Garhwal Rifles.[27][28][18][23] Initially assigned as a public relations officer in the General Staff Branch,[28] Faiz received rapid promotions in succession to acting captain on 18 July 1942, war-substantive lieutenant and temporary captain on 1 November 1942, acting major on 19 November 1943 and to temporary major and war-substantive captain on 19 February 1944.[27] On 30 December 1944, he received a desk assignment as an assistant director of public relations on the staff of the North-Western Army, with the local rank of lieutenant-colonel.[29][23] For his service, he was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire, Military Division (MBE) in the 1945 New Year Honours list.[30] Faiz served with a unit led by Akbar Khan, a left-wing officer and future Pakistan Army general. He remained in the army for a short period after the war, receiving promotion to acting lieutenant-colonel in 1945 and to war-substantive major and temporary lieutenant-colonel on 19 February 1946.[31] In 1947, Faiz opted for the newly established State of Pakistan. However, after witnessing the 1947 Kashmir war with India, Faiz decided to leave the army and submitted his resignation in 1947.[23] Internationalism and communismFaiz believed in internationalism and emphasised the philosophy of the global village.[17] In 1947, he became editor of the Pakistan Times and in 1948, he became vice-president of the Pakistan Trade Union Federation (PTUF).[17] In 1950, Faiz joined the delegation of Prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan, initially leading a business delegation in the United States, attending the meeting at the International Labour Organization (ILO) at San Francisco.[17] During 1948–50, Faiz led the PTUF's delegation in Geneva, and became an active member of World Peace Council (WPC).[17] Faiz was a well-known communist in the country and had been long associated with the Communist Party of Pakistan, which he founded in 1947 along with Marxist Sajjad Zaheer and Jalaludin Abdur Rahim.[32] Faiz had his first exposure to socialism and communism before the independence of State of Pakistan which he thought was consistent with his progressive thinking.[24] Faiz had long associated ties with the Soviet Union, a friendship with atheist country that later honoured him with high award. Even after his death, the Russian government honoured him by calling him "our poet" to many Russians.[24] However his popularity was waned in Bangladesh after 1971 when Dhaka did not win much support for him.[24] Faiz and other pro-communists had no political role in the country, despite their academic brilliance.[32][self-published source] Although Faiz was a not a hardcore or far-left communist, he spent most of the 1950s and 1960s promoting the cause of communism in Pakistan.[32] During the time when Faiz was editor of the Pakistan Times, one of the leading newspapers of the 1950s, he lent editorial support to the party. He was also involved in the circle lending support to military personnel (e.g. Major General Akbar Khan). His involvement with the party and Major General Akbar Khan's coup plan led to his imprisonment later. Later in his life, while giving an interview with a local newspaper, Faiz was asked by the interviewer if he was a communist. He replied with characteristic nonchalance: "No. I am not, a communist is a person who is a card carrying member of the Communist party. The party is banned in our country. So how can I be a communist?...".[33] Rawalpindi plot and exileLiaquat Ali Khan's government failure to capture Indian-administered Kashmir had frustrated the military leaders of the Pakistan Armed Forces in 1948, including Jinnah. A writer had argued that Jinnah had serious doubt of Ali Khan's ability to ensure the integrity and sovereignty of Pakistan.[34] After returning from the United States, Ali Khan imposed restrictions on Communist party as well as Pakistan Socialist Party. Although the East Pakistan Communist Party had ultimate success in East-Pakistan after staging the mass protest to recognise Bengali language as national language. After Jinnah founded it, the Muslim League was struggling to survive in West-Pakistan. Therefore, Prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan imposed extreme restrictions and applied tremendous pressure on the communist party that ensured it was not properly allowed to function openly as a political party. The conspiracy had been planned by left-wing military officer and Chief of General Staff Major-General Akbar Khan. On 23 February 1951, a secret meeting was held at General Akbar's home, attended by other communist officers and communist party members, including Marxist Sajjad Zaheer and communist Faiz.[35] General Akbar assured Faiz and Zaheer that the communist party would be allowed to function as a legitimate political party like any other party and to take part in the elections.[35] But, according to communist Zafar Poshni who maintained, in 2011, that "no agreement was reached, the plan was disapproved, the communists weren't ready to accept General's words and the participants dispersed without meeting again".[35] However the next morning, the plot was foiled when one of the communist officer defected to the ISI revealing the motives behind the plot. When the news reached the Prime minister, orders for massive arrests were given to the Military Police by the Prime minister. Before the coup could be initiated, General Akbar among other communists were arrested, including Faiz.[36] In a trial led by the Judge Advocate General branch's officers in a military court, Faiz was announced to have spent four years in Montgomery Central Jail (MCJ),[37] due to his influential personality, Liaquat Ali Khan's government continued locating him in Central Prison Karachi and the Central Jail Mianwali.[38] The socialist Huseyn Suhravardie was his defence counselor.[38] Finally on 2 April 1955,[18] Faiz's sentence was commuted by the Prime minister Huseyn Suhrawardy, and he departed to London, Great Britain soon after.[38] In 1958, Faiz returned but was again detained by President Iskander Mirza, who allegedly blamed Faiz for publishing pro-communist ideas and for advocating a pro-Moscow government.[36] However, due to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's influence on Ayub Khan, Faiz's sentence was commuted in 1960 and he left for Moscow, Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, eventually settling in London, United Kingdom.[38] Return to Pakistan and government work In 1964, Faiz finally returned to his country and settled down in Karachi, and was appointed Rector of Abdullah Haroon College.[18] Having served as the secretary of the Pakistan Arts Council from 1959 to 1962, he became its vice-president the same year.[24] In 1965, Faiz was first brought to government by the charismatic democratic socialist Zulfikar Ali Bhutto who was serving as Foreign minister in the presidency of Ayub Khan.[18] Bhutto lobbied for Faiz and gave him an honorary capacity at the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (MoIB) working to rallying the people of West-Pakistan to fight against India to defend their motherland.[18] During the 1971 Winter war, Faiz rallied to mobilise the people, writing poems and songs that opposed the bloodshed during the Bangladesh Liberation War.[39] In 1972, Prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto brought him back when Bhutto appointed Faiz as Culture adviser at the Ministry of Culture (MoCul) and the Ministry of Education (MoEd).[17][24] Faiz continued serving in Bhutto's government until 1974 when he took retirement from the government assignments.[17][24] Faiz had strong ties with Bhutto and was deeply upset upon Bhutto's removal by Chief of Army Staff General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq in 1977 in a military coup code-named Fair Play.[40] Again, Faiz was monitored by Military Police and his every move was watched.[35] In 1979, Faiz departed from Pakistan after learning the news that Bhutto's execution had taken place.[35] Faiz took asylum in Beirut, Lebanon, where he edited the Egyptian- and Soviet-sponsored magazine Lotus and met well-known Arab figures like Edward Said and Yasser Arafat,[41] but returned to Pakistan in poor health after the renewal of the Lebanon War in 1982.[42] Themes and writing styleFaiz's early poetry focused on traditional tropes of romantic love, beauty, and heartbreak but eventually expanded to include themes of justice, rebellion, politics, and the interconnectedness of humanity.[19] Therefore, although many of Faiz's poems focus on themes of romantic love and loss,[43] most literary critics do not consider him primarily a romantic poet, emphasising that themes of justice and revolution take precedence in his extensive body of work.[44] Other critics see his poetry as an unconventional fusion of love and revolution that appeals to the new-age reader "who loves his beloved yet lives for humanity."[45] Faiz's poetry is replete with progressivist and revolutionist ideas and he is often referred to as "an artistic rebel."[46] He is widely considered the poet of the oppressed and downtrodden classes and is known for highlighting their poverty, social discrimination, economic exploitation, and political repression.[44] His poetry was heavily leftist as well as anti-capitalist in tone and ideas,[44] and his poems are almost always a reflection of his time, focusing heavily on the suffering of ordinary people.[46] Many of Faiz's poems also revolve around themes of home, exile, and loss, leading UCLA researcher Aamir R. Mufti to assert that one of the predominant themes in Faiz's poetry is the meaning, implications, and legacy of the partition of India.[47] Faiz's writing style is sometimes characterised as occupying a space between romance and love on the one hand and realism and revolution on the other.[45][46] Although he wrote prolifically on the topics of justice, resistance, and revolution, Faiz rarely allowed political rhetoric to overpower his poetry.[46] Not a proponent of the "art for art's sake" philosophy, Faiz believed that art that does not inspire people to take action is not great art.[46] Faiz's poetry often features religious symbolism inspired by Sufism and not by religious dogma.[46][48] Faiz's grandson, Dr. Ali Madeeh Hashmi, has asserted that he was particularly influenced by Sufi figures such as Rumi, that he regretted not having memorized more of the Qur'an, and that ideologically he proposed a form of Islamic socialism.[49] Faiz's prose works tend to be written in strict classical Urdu diction while his poetry is known to have a more conversational and casual tenor.[19] His ghazals are often hailed for skillfully infusing socio-economic and political issues into conventional motifs of the ghazal such as love and separation.[19] Critics have noted that many of Faiz's poems start by making the reader aware of dire socio-political realities but ultimately strike a note of encouragement and hope that desperate circumstances will inevitably change for the better.[45] Some critics have argued that verses written by Faiz in the final years of his life differ in tone and content from the poetry he wrote when he was younger, particularly the poems written while he was incarcerated. His later-stage poetry is said to be more universal in tone, possessing a greater urgency for change and action, and as being more explicit and forthright in its challenge to "decadent tradition."[9] Death and legacy Last daysFaiz died in Lahore, Punjab in 1984, from complications of lung and heart disease[6] shortly after being nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature.[42] Recognition in PakistanAlthough living a simple and restless life, Faiz's work, political ideology, and poetry became immortal, and he has often been called as one of the "greatest poets" of Pakistan.[50][51] Faiz remained an extremely popular and influential figure in the literary development of Pakistan's arts, literature, and drama and theatre adaptation.[52] In 1962, Faiz was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize which enhanced the relations of his country with the Soviet Union which at that time had been hostile and antagonistic relations with Pakistan.[53] The Lenin Peace Prize was a Soviet equivalent of Nobel Peace Prize, and helped lift Faiz's image even higher in the international community.[53] It also brought Soviet Union and Pakistan much closer, offering possibilities for bettering the lives of their people. Most of his work has been translated into the Russian language.[53] Faiz, whose work is considered the backbone of development of Pakistan's literature, arts and poetry, was one of the most beloved poets in the country.[53] Along with Allama Iqbal, Faiz is often known as the "Poet of the East".[54] While commenting on his legacy, classical singer Tina Sani said:

Accolades and international recognitionFaiz was the first Asian poet to receive the Lenin Peace Prize, awarded by the Soviet Union in 1962.[55] In 1976 he was awarded the Lotus Prize for Literature.[55] He was also nominated for the Nobel Prize shortly before his death in 1984.[56] At the Lenin Peace Prize ceremony, held in the grand Kremlin hall in Moscow, Faiz thanked the Soviet government for conferring the honour, and delivered an acceptance speech, which appears as a brief preface to his collection Dast-i-tah-i-Sang (Hand Under the Rock):

In 1990, Faiz was posthumously honoured by the Pakistan Government when the ruling Pakistan Peoples Party led by Prime minister Benazir Bhutto awarded Faiz the highest civilian award, the Nishan-e-Imtiaz, in 1990.[1][57] In 2011, the Pakistan Peoples Party's government declared the year 2011 as "the year of Faiz Ahmad Faiz".[57] In accordance, the Pakistan Government set up a "Faiz Chair" at the Department of Urdu at the Karachi University and at the Sindh University,[58] followed by the Government College University of Lahore established the Patras, Faiz Chair at the Department of Urdu of the university, also in 2011.[59] The same year, the Government College University (GCU) presented golden shields to the University's Urdu department. The shields were issued and presented by the GCU vice-chancellor Professor Dr. Khaleequr Rehman, who noted and further wrote: "Faiz was poet of humanity, love and resistance against oppression".[54] In 2012, at the memorial ceremony that was held at the Jinnah Garden to honour the services of Faiz by the left-wing party Avami National Party and Communist Party, participants chanted: "The Faiz of workers is alive! The Faiz of farmers is alive...! Faiz is alive....!" at the end of the ceremony.[60] In popular cultureA collection of some of Faiz's celebrated poetry was published in 2011, under the name of "Celebrating Faiz" edited by D P Tripathi. The book also included tributes by his family, by contemporaries and by scholars who knew of him through his poetry. The book was released on the occasion of Mahatma Gandhi's birth anniversary in the Punjab province in Pakistan.[61] A Faiz poem is read in the British 2021 television sitcom We Are Lady Parts. In Nawaaz Ahmed's novel, Radiant Fugitives, a Faiz poem is recalled as the poem that the mother, Nafeesa, recites during a college jubilee celebration that attracts her soon-to-be husband.[62] Faiz's poetic compositions have featured regularly on Coke Studio Pakistan. In Season 3, "Mori Araj Sunno" was performed by Tina Sani, which also fused "Rabb Sacheya". Later in Season 5, "Rabba Sacheya" was performed by Atif Aslam. Season 10 featured his poem "Bol Ke Lab Azaad Hain Tere" (performed by Shafqat Amanat Ali) and "Mujhse Pehli Si Mohabbat" (performed by Humaira Channa & Nabeel Shaukat Ali). Season 11 featured Faiz's well-known revolutionary song "Hum Dekhenge" (performed by featured artists for the season).[63] Season 12 featured the songs "Gulon Main Rang" (performed by Ali Sethi) and "Aaye Kuch Abr" (performed by Atif Aslam). "Gulon Main Rang", composed and performed by Mehdi Hasan, was later performed by Arijit Singh, for Bollywood movie Haider.[64] TranslationsFaiz's poetry has been translated into many languages including English and Russian.[65] A Balochi poet, Mir Gul Khan Nasir, who was also a friend of Faiz Ahmad Faiz, translated his book Sar-e-Wadi-e-Seena into Balochi with the title Seenai Keechag aa. Gul Khan's translation was written while he was in jail during Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's regime for opposing the government's policies. It was only published in 1980, after Zia-ul-Haq toppled Bhutto's government and freed all the political prisoners of his (Bhutto's) regime. Victor Kiernan, British Marxist historian translated Faiz Ahmad Faiz's works into English, and several other translations of whole or part of his work into English have also been made by others;[66] a transliteration in Punjabi was made by Mohinder Singh.[citation needed] Faiz Ahmad Faiz, himself, also translated works of notable poets from other languages into Urdu. In his book "Sar-i Waadi-i Seena سرِ وادیِ سینا" there are translations of the famous poet of Dagestan, Rasul Gamzatov. "Deewa", a Balochi poem by Mir Gul Khan Nasir, was also translated into Urdu by Faiz.[67][68] Faiz Foundation Trust and International Faiz FestivalCreated in 2009,[69] the Faiz Foundation Trust holds the copyright for all literary works of Faiz Ahmad Faiz.[70] It also runs a not-for-profit organisation known as Faiz Ghar (House of Faiz) with the mission to promote the humanistic ideas of Faiz as well as art, literature, and culture in general.[70] The organisation also houses Faiz's personal library and much of his memorabilia including rare photographs, academic diplomas, and his letters and manuscripts.[70] In 2015, the Faiz Foundation Trust launched the inaugural International Faiz Festival in collaboration with the Lahore Arts Council at Alhamra in Lahore, Pakistan.[71][72] Held regularly since then, the festival is aimed at promoting Urdu poetry, music, literature, drama, and human rights in Pakistan.[71][73][74] Personal lifeIn 1941, Faiz became involved with Alys Faiz, a British national and a member of Communist Party of the United Kingdom, who was a student at the Government College University where Faiz taught poetry.[75] The marriage ceremony took place in Srinagar, while the nikah ceremony was performed at Pari Mahal. Faiz and his wife lived in the building that is now Government College for Women, M.A. Road. Faiz's host, M. D. Taseer, who was serving as the college principal at the time, was later married to Alys's sister, Christobel. Faiz's nikah ceremony was attended by Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, Ghulam Mohammed Sadiq, and Sheikh Abdullah among others.[76] While Alys opted for Pakistan citizenship, she was a vital member of Communist Party of Pakistan and played a significant role in Rawalpindi Conspiracy Case when she brought together the communist mass. Faiz and his wife have two daughters, Salima Hashmi and Muneeza Hashmi.[75] Bibliography

Plays, music, and dramatic productions on Faiz

See alsoNotes

References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||