|

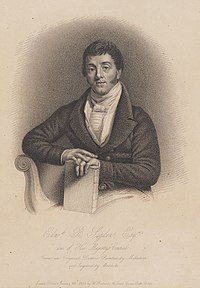

Edward Sugden, 1st Baron St Leonards

Edward Burtenshaw Sugden, 1st Baron Saint Leonards, PC, PC (Ire), DL (12 February 1781 – 29 January 1875) was a British lawyer, judge and Conservative politician. BackgroundSugden was the son of a high-class hairdresser and wig-maker in Westminster, London. Details of his education are said to be "obscure". It appears that he was mostly self-taught, although he also attended a private school. His humble origins and rapid rise were frequently remarked upon by his contemporaries: when he first attempted to enter Parliament, he was heckled at hustings for being the son of a barber. Later, Thomas Fowell Buxton would write that "there are few instances in modern times of a rise equal to that of Sir Edward Sugden". Legal and political careerAfter practising for some years as a conveyancer, Sugden was called to the bar at Lincoln's Inn in 1807, having already published his well-known Concise and Practical Treatise on the Law of Vendors and Purchasers of Estates. In 1822 he was made King's Counsel. He was returned at different times for various boroughs to the House of Commons, where he made himself prominent by his opposition to the Reform Bill of 1832.[1] He was appointed Solicitor General in 1829, receiving the customary knighthood.[2] As Solicitor-General he took a narrow view of Jewish emancipation, arguing that "They had possessed nothing; they held nothing. They had no civil rights; they never had any."[3] In 1834–5 Sugden was made Lord Chancellor of Ireland in Peel's first ministry, and was sworn of the Privy Council on 15 December 1834. Sugden was again the Irish Lord Chancellor in Peel's second ministry, serving from 1841 to 1846. In 1849, Sugden published A Treatise on the Law of Property as administered in the House of Lords, in which he criticised the decisions given in the House of Lords when acting as a Court of Appeal. In Lord Derby's first government in 1852 he became Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain and was raised to the peerage as Baron Saint Leonards, of Slaugham in the County of Sussex.[4] In this position he devoted himself with energy and vigour to the reform of the law (note his important dissenting opinion in Jorden v Money (1854) 5 HL Cas 185); Lord Derby on his return to power in 1858 again offered him the same office, which from considerations of health he declined. He continued, however, to take an active interest especially in the legal matters that came before the House of Lords, and bestowed his particular attention on the reform of the law of property.[1] He championed the fulfilment of the will of J. M. W. Turner with regard to his art bequests in 1857–70. Publications Lord Saint Leonards was the author of various important legal publications, many of which have passed through several editions. Besides the treatise on purchasers already mentioned, they include Powers, Cases decided by the House of Lords, Gilbert on Uses, New Real Property Laws and Handybook of Property Law, Misrepresentations in Campbells Lives of Lyndhurst and Brougham, corrected by St Leonards.[1] FamilyLord Saint Leonards married Winifred, daughter of John Knapp, in 1808. The marriage was an elopement, which resulted in Lady Saint Leonards’s never being invited to the puritanical Victorian court over the course of their five decade marriage.[5] She died in May 1861. Lord Saint Leonards died at Boyle Farm, Thames Ditton, in January 1875, aged 93, and was succeeded in the barony by his grandson, Edward. Sugden Road in nearby Long Ditton is named after him. Inheritance disputeAfter his death his will was missing but his daughter, Charlotte Sugden, was able to recollect the contents of a most intricate document, and in the action of Sugden v. Lord Saint Leonards (L.R. 1 P.D. 154) the Court of Chancery accepted her evidence and granted probate, admitting into the probate a paper propounded as containing the provisions of the lost will. This decision established the proposition that the contents of a lost will, that can be proven to have existed, may be proved by secondary evidence, even of a single witness.[1] Charlotte Sugden submitted sworn testimony that Lord Saint Leonards was in the habit of reading his will every night, such that his daughter had to listen to it and over some years memorised it. This decision became a well known fact and narrow precedent in legal circles, departing from provisions of the Wills Act 1837 which remained the principal legislation governing an area shaped by equity and later by common law.[6] Arms

Notes

References

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||