|

Education in Iran

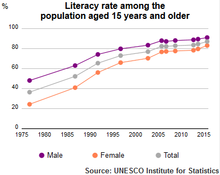

Education in Iran is centralized and divided into K-12 education plus higher education. Elementary and secondary education is supervised by the Ministry of Education and higher education is under the supervision of Ministry of Science, Research and Technology and Ministry of Health and Medical Education for medical sciences. As of 2016, around 94% of the Iranian adult population is literate.[1] This rate increases to 97% among young adults ages between 15 and 24 without any gender consideration.[2] By 2007, Iran had a student-to-workforce population ratio of 10.2%, standing among the countries with the highest ratio in the world.[3] Primary school (Dabestân, دبستان) starts at the age of 6 for a duration of six years. Junior high school (Dabirestân دوره اول دبیرستان), also known as middle school, includes three years of Dabirestân from the seventh to the ninth grade. Senior high school (Dabirestân, دوره دوم دبیرستان), including the last three years, is mandatory. The student at this level can study theoretical, vocational/technical, or manual fields, each program with its specialties. Ultimately, students are given a high school diploma.[4] The requirement to enter into higher education is to have a high school diploma, and passing the national university entrance examination, Iranian University Entrance Exam (Konkur کنکور), which is similar to the French baccalauréat exam (for most of universities and fields of study). Iran suffers from a problem of over education and falsified academic degrees.[5] [6] Universities, institutes of technology, medical schools and community colleges provide the higher education. Higher education is sectioned by different levels of diplomas: Fogh-e-Diplom or Kārdāni after two years of higher education, Kārshenāsi (also known under the name "license") is delivered after four years of higher education (bachelor's degree). Kārshenāsi-ye Arshad is delivered after two more years of study (master's degree). After which, another exam allows the candidate to pursue a doctoral program (Ph.D.).[4] The Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI)[7] finds that Iran is fulfilling only 91.0% of what it should fulfill for the right to education based on the country's income level.[8] HRMI breaks down the right to education by examining the rights to both primary and secondary education. While considering Iran's income level, the nation is achieving 99.2% of what should be possible based on its resources (income) for primary education but only 82.9% for secondary education.[8] The government banned opening new private schools in 2023.[9] History of education in IranPre-Islamic IranScholars have discovered documents from around 550 BC relating to an emphasis on education in ancient Persia (modern-day Iran).[10] The documents urged people to gain knowledge to understand God better and to live a life of prosperity.[10] Religious schools were set up in limited areas to serve the government. Although most of the problems focused on religious studies, there were also lessons regarding administration, politics, technical skills, military, sports, and arts. The first higher education organization, Gundeshapur or Jondishapoor (which still exists), was formed during the Sassanid period, around the third century.[10] Safavid dynastyThis dynasty marks the first of modern education in Iran.[10] There was a mixed emphasis on Islamic values and scientific advancements.[10] Muzaffari eraFormed in 1898, the Educational Committee (Anjuman-i Ma'arf) was the first organized program to promote educational reform not funded by the state.[11] The committee was composed of members of foreign services, ulama, wealthy merchants, physicians, and other prominent people. The conflicting interests of people involved led to difficulties enacting, however they did succeed in the opening of many new primary and secondary educational schools. It also created a public library, offered adult classes, published an official newspaper (Ruznamah-i Ma'arif), and established a printing company called The Book Printing Company (Shirkat-i Tab'-i Kitab).[11] The Literacy Corps (1969–1979)The literacy corps took place over the White Revolution, which occurred under Muhammad Reza Pahlavi.[12] The government believed that most of the population was illiterate, and the Literacy Corps was an attempt to change the statistics. The program included hiring young men who had a degree in secondary education to serve in the Literacy Corps and involved teaching children between the ages of 6 and 12, most of whom had not attended 2nd-grade education, to read. The goal was to improve literacy in Iran cheaply and efficiently, which they also believed would improve workmanship. 200,000 young men and women participated in the Literacy Corps, teaching 2.2 million boys and girls and over a million adults.[12] In many cases, the volunteers would continue to work as educators after their conscription ended.[12] Post-Islamic RevolutionAt first, post-1979 Islamic Revolution placed heavy emphasis on educational reforms.[10] Politicians wanted Islamic values to be present within the schooling system as quickly as possible. However, pressures due to the Iran-Iraq War and economic disparities forced plans for education back as other issues took priority.[10] Some significant changes were made. First came the Islamization of textbooks. Schools were then segregated according to the sex of students. Observation of Islamic Law in schools became mandatory and religious ceremonies was maintained.[10] By the 1990s, more significant changes arose.[10] The annual academic system switched to a credit-based system. For example, if a student were to fail a class, rather than repeating the whole year, they would retake the credits. The mandatory duration of high school was shortened from four years to three. However, the fourth year was still available as an option to bridge the gap between high school and university.[10] Also, many technical and vocational programs were added to help train students for the workforce, which proved to be popular with students. Modern education The first Western-style public schools were established by Haji-Mirza Hassan Roshdieh. Amir Kabir (the Grand Minister) helped establish the first modern Iranian college in the mid-nineteenth century. In the nineteenth-century, the first Iranian university, modeled after European universities, was established during the first Pahlavi period.[13] There are both free public schools and private schools in Iran at all levels, from elementary school through university. Education in Iran is highly centralized. The Ministry of Education oversees educational planning, financing, administration, curriculum, and textbook development. Teacher training, grading, and examinations are also the responsibility of the ministry. At the university level, however, every student attending public schools is required to commit to serving the government for several years, typically equivalent to those spent at the university, or pay it off for a meager price (typically a few hundred dollars) or completely free if one can prove inability to pay to the Islamic government (post-secondary and university). During the early 1970s, efforts were made to improve the educational system by updating the school curriculum, introducing modern textbooks, and training more efficient teachers.[14] The 1979 revolution continued the country's emphasis on education, with the new government putting its stamp on the process. The most significant change was the Islamization of the education system. All students were segregated by sex. In 1980, the Cultural Revolution Committee was formed to oversee the institution of Islamic values in education. An arm of the committee, the Center for Textbooks (composed mainly of clerics), produced 3,000 new college-level textbooks reflecting Islamic views by 1983.[citation needed] Teaching materials based on Islam were introduced into the primary grades within six months of the revolution. In 2014, it was reported that around 4 million children eligible for a K-12 education had dropped out of the school system.[15] Grades

BudgetEach year, 20% of government spending and 5% of GDP goes to education, a higher rate than most developing countries. 50% of education spending is devoted to secondary education, and 21% of the annual state education budget is devoted to the provision of tertiary education.[17] Unconstitutional changeIn 2024 Supreme cultural revolution staff introduced a law that makes it illegal for people to protest universities and government educational law deemed to be constitutional change without a public vote or referendum.[18][19][20] Mandatory Islamic pray timeIn October 2023 government ordered mandatory half hour Islamic prayer everyday for schoolkids.[21] College kids have to learn General Solomani's will.[22] Education reformThe Fourth Five-Year Development Plan (2005–2010) has envisaged upgrading the quality of the educational system at all levels, as well as reforming education curricula, and developing appropriate programs of vocational training, a continuation of the trend towards labor market-oriented education and training.[23] With the new education reform plan in 2012, the pre-university year will be replaced with an additional year in elementary school.[citation needed] Students will have the same teacher for the first three years of primary school. Emphasis will be made on research, knowledge production, and questioning instead of math and memorizing alone. In the new system, the teacher will no longer be the only instructor but a facilitator and guide.[citation needed] Other more general goals of the education reform are:

Hybrid method learning programEver since after the pandemic the government supreme council of education has a program for mass hybrid teaching in universities with learning management system and schools with Shad software. The government offers grants for research into hybrid education.[24][25][26] PrivatizationIn recent decades, schools in Iran have come to be viewed as corporate businesses with steadily rising injustice.[27][28] Iranian education has witnessed a mass inflation with the rising takeover of private schools in big cities like Isfahan.[29] The cost of education in a public school could be around 14 million dollars a year per student.[30] [31][32] In 2023, Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of Iran called public schools weak and for poor people compared to private schools.[33] Studying for a 1-year term in private schools may cost 50 million dollars as of July 2023.[34] Teacher shortageAs of 2023, Iran has about 950,000 teachers; there is a shortage of about 60,000 teachers in the country. As of 2023, there are a million teachers. Half of all schools lack school counselors; there is a shortage of about 30,000 people in this position.[35][36][37] In the southeastern province of Sistan and Baluchestan, schools themselves are in short supply, and about 30% of students are unable to attend school.[38][39] Teacher educationFarhangian University is the university of teacher education and human resource development in the Ministry of Education.[citation needed] Teacher training centers in Iran are responsible for training teachers for primary, orientation cycle, and gifted children's schools. These centers offer four-year programs leading to a B.A. or B.S. degree in teaching the relevant subject. At a minimum, students that enter teacher training centers have completed a high school diploma. A national entrance examination is required for admission. There are 98 teacher training centers in Iran, all belonging to Farhangian University. Teacher education in Iran has been considered more centralized than in other Western countries such as Great Britain.[10] Foreign languagesPersian is officially the national language of Iran. Arabic, as the language of the Quran, is taught grades 7–12. In addition to Arabic, students are required to take one foreign language class in grades 7–12. Although German and French are offered in some schools and textbooks have been written, English continues to be the most desired language.[40] Iran has added the French language since 2022 new school year to the regular school curriculum for students who wish to take French instead of English in an effort to break the monopoly of English. Kanoun-e-Zabaan-e-Iran or Iran's Language Institute affiliated with the Center for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults was founded in 1979. Persian, English, French, Spanish, German, Russian, and Arabic are taught to over 175,000 students each term.[40] English is studied in first and second high school. However, the quality of English education in schools could be more satisfactory, and most students have to take English courses in private institutes to obtain better English fluency and proficiency.[41] Before 2018, some primary schools also taught English. However, in January 2018, a senior educational official announced that teaching English would be banned in primary schools, including non-government schools.[42] Presently, there are over 5000 foreign language schools in the country, 200 of which are in Tehran. A few television channels air weekly English and Arabic language sessions, particularly for university candidates preparing for the annual entrance test.[40] Internet and distance educationFull Internet service is available in all major cities and it is very rapidly increasing. Many small towns and even some villages now have full Internet access. The government aims to provide 10% of government and commercial services via the Internet by end-2008 and to equip every school with computers and connections by the same date.[43] Payame Noor University (established 1987) as a provider exclusively of distance education courses is a state university under the supervision of the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology.[44] As of 2020, 70% of Iranian schools linked to the local intranet.[citation needed] Higher educationAs of 2013, 4.5 million students are enrolled in universities, out of a total population of 75 million.[2]Ayse, Valentine; Nash, Jason John; Leland, Rice (January 2013). The Business Year 2013: Iran. London, U.K.: The Business Year. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-908180-11-7. Iranian universities graduate almost 750,000 annually.[45] The tradition of university education in Iran goes back to ancient times. By the twentieth century, however, the system had become antiquated and was remodeled along French lines. The country's 16 universities were closed after the 1979 revolution and were then reopened gradually between 1982 and 1983 under Islamic supervision. While the universities were closed, the Cultural Revolution Committee investigated professors and teachers and dismissed those who were believers in Marxism, liberalism, and other "imperialistic" ideologies. The universities reopened with Islamic curricula. In 1997, all higher-level institutions had 40,477 teachers and enrolled 579,070 students. Admission to public universities, some are tuition-free, is based solely on performance on the nationwide Konkour exam. Some alternative to the public universities is the Islamic Azad University which charges high fees.[46] The syllabus of all the universities in Iran is decided by a national council as a result the difference of the quality of education among the universities is only based on the location and the quality of the students and the faculty members. Among all top universities in the country there are three universities each notable for some reasons: The University of Tehran (founded in 1934) has 10 faculties, including a department of Islamic theology. It is the oldest (in the modern system) and biggest university in Iran. It has been the birthplace of several social and political movements. Tarbiat Modares University (means: professor training university) also located in Tehran is the only exclusively post-graduate institute in Iran. It only offers master's, PhD, and postdoc programs. It is also the most comprehensive Iranian university in the sense that it is the only university under the Iranian Ministry of Science System that has a Medical School. All other Medical Schools in Iran are a separate university and governed under the Ministry of Health; for example, the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (commonly known as Medical School of Tehran University) is in fact separate from Tehran University. Sharif University of Technology, Amirkabir University of Technology, and Iran University of Science and Technology also located in Tehran are nationally well known for taking in the top undergraduate engineering and science students; and internationally recognized for training competent undergraduate students. It has probably the highest percentage of graduates who seek higher education abroad.[citation needed] K. N. Toosi University of Technology is among most prestigious universities in Tehran. Other major universities are at Shiraz, Tabriz, Isfahan, Mashhad, Ahvaz, Kerman, Kermanshah, Babolsar, Rasht, and Orumiyeh. There are about 50 colleges and 40 technological institutes.[47] In 2009, 33.7% of all those in the 18–25 age group were enrolled in one of the 92 universities, 512 Payame Noor University branches, and 56 research and technology institutes around the country. There are currently some 3.0 million university students in Iran and 1.0 million study at the 500 branches of Islamic Azad University.[2] Iran had 1 million medical students in 2011.[citation needed]

Starred studentsStarred student دانشجوی ستاره دار is a common name for a list of Iranian higher education students who are charged with a religious or political conviction. These students are registered in university under specific circumstance or not at all as punishment.[48][49][50] Student Affairs Organization and Ministry of Science and Research denied existence of such lists.[51][52][53] EntrepreneurshipIn recent decades Iran has shown an increasing interest in various entrepreneurship fields, in higher educational settings, policy making and business. Although primary and secondary school textbooks do not address entrepreneurship, several universities including Tehran University and Sharif University, offer courses on entrepreneurship to undergraduate and graduate students.[54][55][56][57] In accordance with the third five-year development plan, the "entrepreneurship development plan in Iranian universities", (known as KARAD Plan) was developed, and launched in twelve universities across the country, under the supervision of Management and Planning Organization and the Ministry of Science, Research and Technology.[58] Women in educationIn September 2015, women comprised more than 70% of all universities' student body in Iran.[59] This high level of achievement and involvement in high education is a recent development of the past decades. The right to a respectable education has been a major demand of the Iranian women's movement starting in the early twentieth century.  Before the 1979 revolution a limited number of women went to male-dominated schools. Most traditional families did not send their girls to school because the teachers were men or the school was not Islamic.[60] During the 1990s, women's enrollment in educational institutions began to increase. The establishment and the expansion of private universities Daneshgah-e-azad-e Islami also contributed to the increasing enrollment for both women and men. Under the presidency of Rafsanjani and the High council of cultural Revolution, the Women's social and cultural council was set up and charged with studying women's legal, social, and economic problems. The council, with the support of Islamic feminists, worked to lift all restrictions on women entering any field of study in 1993. After the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his new regime prioritized Islamizing the Iranian education system for both women and men.[61] When Khomeini died in 1989, under president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, many but not all restrictions on women's education were lifted, albeit with controversy. The right to education for everyone without discrimination is explicitly guaranteed under Iran's constitution and international documents, which Iran has accepted or to which it is a party.[62] Some scholars believe that women have poor access to higher education because of specific policies and the oppression of women's rights in Iran's strictly Islamic society. However, Iranian women have fair access to higher education as seen by a significant increase in female enrollment and graduation rates, as female university students now outnumber males. Iranian women emerge to more prominent positions in the labor force, demonstrating professional women's presence and confidence in the public sphere. The opportunities for women's education and their involvement in higher education have grown exponentially after the Iranian Revolution.[63] According to UNESCO world survey, Iran has the highest female to male ratio at the primary level of enrollment in the world among sovereign nations, with a girl to boy ratio of 1.22:1.[64] Schools for Gifted ChildrenThe National Organization for Development of Exceptional Talents (NODET), also known as SAMPAD (سمپاد), maintains middle and high schools in Iran. These schools were shut down for a few years after the revolution, but later re-opened. Admittance is based on an entrance examination and is very competitive. Their tuition is similar to private schools but may be partially or fully waived depending on the student's financial condition. Some NODET alumni are world-leading scientists. Other schools are Selective Schools which are called "Nemoone Dolati". These schools are controlled by the government and have no fees. Students take this entrance exam alongside NODET exams. Organization for Educational Research and Planning (OERP)OERP is a government affiliated, scientific, learning organization. It has qualitative and knowledge-based curricula consistent with the scientific and research findings, technological, national identity, Islamic and cultural values. OERP's Responsibilities:

Prominent high schools in Iran: historical and current

International Baccalaureate schoolsIran has three International Baccalaureate (IB) schools. They are Mehr-e-Taban International School,[66] Shahid Mahdavi International School,[67] and Tehran International School.[68] Mehr-e-Taban International School is an authorized IB world school in Shiraz offering the Primary Years Programme, Middle Years Programme and Diploma Programme. Shahid Mahdavi School is an IB world school in Tehran offering the Primary Years Programme and Middle Years Programme. Tehran International School is an IB world school in Tehran offering the Diploma Programme. Statistics

See also

Notes

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Education in Iran.

|