|

Duckworth–Lewis–Stern method

The Duckworth–Lewis–Stern method (DLS method or DLS) previously known as the Duckworth–Lewis method (D/L) is a mathematical formulation designed to calculate the target score (number of runs needed to win) for the team batting second in a limited overs cricket match interrupted by weather or other circumstances. The method was devised by two English statisticians, Frank Duckworth and Tony Lewis, and was formerly known as the Duckworth–Lewis method (D/L).[1] It was introduced in 1997, and adopted officially by the International Cricket Council (ICC) in 1999. After the retirement of both Duckworth and Lewis, the Australian statistician Steven Stern became the custodian of the method, which was renamed to its current title in November 2014.[2][3] In 2014, he refined the model to better fit modern scoring trends, especially in T20 cricket, resulting in the updated Duckworth-Lewis-Stern method.[4] This refined method remains the standard for handling rain-affected matches in international cricket today. The target score in cricket matches without interruptions is one more than the number of runs scored by the team that batted first. When overs are lost, setting an adjusted target for the team batting second is not as simple as reducing the run target proportionally to the loss in overs, because a team with ten wickets in hand and 25 overs to bat can play more aggressively than if they had ten wickets and a full 50 overs, for example, and can consequently achieve a higher run rate. The DLS method is an attempt to set a statistically fair target for the second team's innings, which is the same difficulty as the original target. The basic principle is that each team in a limited-overs match has two resources available with which to score runs (overs to play and wickets remaining), and the target is adjusted proportionally to the change in the combination of these two resources. History and creationVarious different methods had been used previously to resolve rain-affected cricket matches, with the most common being the Average Run Rate method, and later, the Most Productive Overs method. While simple in nature, these methods had intrinsic flaws and were easily exploitable:

The D/L method was devised by two British statisticians, Frank Duckworth and Tony Lewis, as a result of the outcome of the semi-final in the 1992 World Cup between England and South Africa, where the Most Productive Overs method was used. When rain stopped play for 12 minutes, South Africa needed 22 runs from 13 balls, but when play resumed, the revised target left South Africa needing 21 runs from one ball, a reduction of only one run compared to a reduction of two overs, and a virtually impossible target given that the maximum score from one ball is generally six runs.[5] Duckworth said, "I recall hearing Christopher Martin-Jenkins on radio saying 'surely someone, somewhere could come up with something better' and I soon realised that it was a mathematical problem that required a mathematical solution."[6][7] The D/L method avoids this flaw: in this match, the revised D/L target of 236 would have left South Africa needing four to tie or five to win from the final ball.[8][nb 1] The D/L method was first used in international cricket on 1 January 1997 in the second match of the Zimbabwe versus England ODI series, which Zimbabwe won by seven runs.[11] The D/L method was formally adopted by the ICC in 1999 as the standard method of calculating target scores in rain-shortened one-day matches. TheoryCalculation summaryThe essence of the D/L method is 'resources'. Each team is taken to have two 'resources' to use to score as many runs as possible: the number of overs they have to receive; and the number of wickets they have in hand. At any point in any innings, a team's ability to score more runs depends on the combination of these two resources they have left. Looking at historical scores, there is a very close correspondence between the availability of these resources and a team's final score, a correspondence which D/L exploits.[12]  The D/L method converts all possible combinations of overs (or, more accurately, balls) and wickets left into a combined resources remaining percentage figure (with 50 overs and 10 wickets = 100%), and these are all stored in a published table or computer. The target score for the team batting second ('Team 2') can be adjusted up or down from the total the team batting first ('Team 1') achieved using these resource percentages, to reflect the loss of resources to one or both teams when a match is shortened one or more times. In the version of D/L most commonly in use in international and first-class matches (the 'Professional Edition'), the target for Team 2 is adjusted simply in proportion to the two teams' resources, i.e. If, as usually occurs, this 'par score' is a non-integer number of runs, then Team 2's target to win is this number rounded up to the next integer, and the score to tie (also called the par score), is this number rounded down to the preceding integer. If Team 2 reaches or passes the target score, then they have won the match. If the match ends when Team 2 has exactly met (but not passed) the par score then the match is a tie. If Team 2 fail to reach the par score then they have lost. For example, if a rain delay means that Team 2 only has 90% of resources available, and Team 1 scored 254 with 100% of resources available, then 254 × 90% / 100% = 228.6, so Team 2's target is 229, and the score to tie is 228. The actual resource values used in the Professional Edition are not publicly available,[13] so a computer which has this software loaded must be used. If it is a 50-over match and Team 1 completed its innings uninterrupted, then they had 100% resource available to them, so the formula simplifies to: Summary of impact on Team 2's target

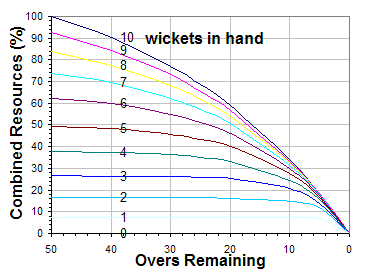

Mathematical theoryThe original D/L model started by assuming that the number of runs that can still be scored (called ), for a given number of overs remaining (called ) and wickets lost (called ), takes the following exponential decay relationship:[14] where the constant is the asymptotic average total score in unlimited overs (under one-day rules), and is the exponential decay constant. Both vary with (only). The values of these two parameters for each from 0 to 9 were estimated from scores from 'hundreds of one-day internationals' and 'extensive research and experimentation', though were not disclosed due to 'commercial confidentiality'.[14]  Finding the value of for a particular combination of and (by putting in and the values of these constants for the particular ), and dividing this by the score achievable at the start of the innings, i.e. finding gives the proportion of the combined run scoring resources of the innings remaining when overs are left and wickets are down.[14] These proportions can be plotted in a graph, as shown right, or shown in a single table, as shown below. This became the Standard Edition. When it was introduced, it was necessary that D/L could be implemented with a single table of resource percentages, as it could not be guaranteed that computers would be present. Therefore, this single formula was used giving average resources. This method relies on the assumption that average performance is proportional to the mean, irrespective of the actual score. This was good enough in 95 per cent of matches, but in the 5 per cent of matches with very high scores, the simple approach started to break down.[15] To overcome the problem, an upgraded formula was proposed with an additional parameter whose value depends on the Team 1 innings.[16] This became the Professional Edition. ExamplesStoppage in first inningsIncreased targetIn the 4th India–England ODI in the 2008 series, the first innings was interrupted by rain on two occasions, reducing the match to 22 overs each. India (batting first) made 166/4. The D/L method increased England's target to 198 from 22 overs. As England knew they had only 22 overs, the expectation is that they could score more runs from those overs than India had from their (interrupted) innings. England made 178/8 from 22 overs, and so the match was listed as "India won by 19 runs (D/L method)".[17] During the 5th ODI between India and South Africa in January 2011, rain halted play twice during the first innings. The match was reduced to 46 overs each. South Africa scored 250/9. The D/L method increased India's target to 268. As the number of overs was reduced during South Africa's innings, this method takes into account what South Africa were likely to have scored if they had known throughout their innings that it would only be 46 overs long. The match was listed as "South Africa won by 33 runs (D/L method)".[18] Decreased targetOn 3 December 2014, Sri Lanka played England and batted first, but play was interrupted when Sri Lanka had scored 6/1 from 2 overs. At the restart, both innings were reduced to 35 overs, and Sri Lanka finished on 242/8. D/L reduced England's target to 236 from 35 overs.[19] Although Sri Lanka had less resource remaining after the interruption than England would have for their whole innings (about 7% less), they had used up 8% of their resource (2 overs and 1 wicket) before the interruption, so the total resource used by Sri Lanka was still slightly more than England had available, hence the slightly decreased target for England. Stoppage in second inningsA simple example of the D/L method being applied was the 1st ODI between India and Pakistan in their 2006 ODI series.[20] India batted first, and were all out for 328. Pakistan, batting second, were 311/7 when bad light stopped play after the 47th over. Pakistan's target, had the match continued, was 18 runs in 18 balls, with three wickets in hand. Considering the overall scoring rate throughout the match, this is a target most teams would be favoured to achieve. And indeed, application of the D/L method resulted in a retrospective target score of 305 (or par score of 304) at the end of the 47th over, with the result therefore officially listed as "Pakistan won by 7 runs (D/L Method)". The D/L method was used in the group stage match between Sri Lanka and Zimbabwe at the T20 World Cup in 2010. Sri Lanka scored 173/7 in 20 overs batting first, and in reply Zimbabwe were 4/0 from 1 over when rain interrupted play. At the restart Zimbabwe's target was reduced to 108 from 12 overs, but rain stopped the match when they had scored 29/1 from 5 overs. The retrospective D/L target from 5 overs was a further reduction to 44, or a par score of 43, and hence Sri Lanka won the match by 14 runs.[21][22] The DLS method was also used after the rain disruption in the 2023 Indian Premier League final, when Chennai Super Kings had scored 4/0 (0.3 overs) and the Gujarat Titans just scored 214/4 (20 overs). The target was reduced at 171 runs from 15 overs from earlier target of 215 runs from 20 overs for Chennai Super Kings. Chennai Super Kings won by 5 wickets by the DLS method. This was achieved by reaching 171/5 from 15 overs. An example of a D/L tied match was the ODI between England and India on 11 September 2011. This match was frequently interrupted by rain in the final overs, and a ball-by-ball calculation of the Duckworth–Lewis 'par' score played a key role in tactical decisions during those overs. At one point, India were leading under D/L during one rain delay, and would have won if play had not resumed. At a second rain interval, England, who had scored some quick runs (knowing they needed to get ahead in D/L terms) would correspondingly have won if play had not resumed. Play was finally called off with just 7 balls of the match remaining and England's score equal to the Duckworth–Lewis 'par' score, therefore resulting in a tie. This example does show how crucial (and difficult) the decisions of the umpires can be, in assessing when rain is heavy enough to justify ceasing play. If the umpires of that match had halted play one ball earlier, England would have been ahead on D/L, and so would have won the match. Equally, if play had stopped one ball later, India could have won the match with a dot ball – indicating how finely-tuned D/L calculations can be in such situations. Stoppages in both inningsDuring the 2012/13 KFC Big Bash League, D/L was used in the 2nd semi-final played between the Melbourne Stars and the Perth Scorchers. After rain delayed the start of the match, it interrupted Melbourne's innings when they had scored 159/1 off 15.2 overs, and both innings were reduced by 2 overs to 18, and Melbourne finished on 183/2. After a further rain delay reduced Perth's innings to 17 overs, Perth returned to the field to face 13 overs, with a revised target of 139. Perth won the game by 8 wickets with a boundary off the final ball.[23][24] Use and updatesThe published table that underpins the D/L method is regularly updated, using source data from more recent matches; this is done on 1 July annually.[25] For 50-over matches decided by D/L, each team must face at least 20 overs for the result to be valid, and for Twenty20 games decided by D/L, each side must face at least five overs, unless one or both teams are bowled out and/or the second team reaches its target in fewer overs. If the conditions prevent a match from reaching this minimum length, it is declared a no result. 1996–2003 – Single versionUntil 2003, a single version of D/L was in use. This used a single published reference table of total resource percentages remaining for all possible combinations of overs and wickets,[26] and some simple mathematical calculations, and was relatively transparent and straightforward to implement. However, a flaw in how it handled very high first innings scores (350+) became apparent from the 1999 Cricket World Cup match in Bristol between India and Kenya. Tony Lewis noticed that there was an inherent weakness in the formula that would give a noticeable advantage to the side chasing a total in excess of 350. A correction was built into the formula and the software, but was not fully adopted until 2004. One-day matches were achieving significantly higher scores than in previous decades, affecting the historical relationship between resources and runs. The second version uses more sophisticated statistical modelling, but does not use a single table of resource percentages. Instead, the percentages also vary with score, so a computer is required.[13] Therefore, it loses some of the previous advantages of transparency and simplicity. In 2002 the resource percentages were revised, following an extensive analysis of limited overs matches, and there was a change to the G50 for ODIs. (G50 is the average score expected from the team batting first in an uninterrupted 50 overs-per-innings match.) G50 was changed to 235 for ODIs. These changes came into effect on 1 September 2002.[27] As of 2014, these resource percentages are the ones still in use in the Standard Edition, though G50 has subsequently changed. The tables show how the percentages were in 1999 and 2001, and what they were changed to in 2002. Mostly they were reduced.

2004 – Adoption of second versionThe original version was named the Standard Edition, and the new version was named the Professional Edition. Tony Lewis said, "We were then [at the time of the 2003 World Cup Final] using what is now known as the Standard Edition. ... Australia got 359 and that showed up the flaws and straight away the next edition was introduced which handled high scores much better. The par score for India is likely to be much higher now."[30] Duckworth and Lewis wrote, "When the side batting first score at or below the average for top level cricket ..., the results of applying the Professional Edition are generally similar to those from the Standard Edition. For higher scoring matches, the results start to diverge and the difference increases the higher the first innings total. In effect there is now a different table of resource percentages for every total score in the Team 1 innings."[13] The Professional Edition has been in use in all international one-day cricket matches since early 2004. This edition also removed the use of the G50 constant when dealing with interruptions in the first innings.[13] The decision on which edition should be used is for the cricket authority which runs the particular competition.[13] The ICC Playing Handbook requires the use of the Professional Edition for internationals.[31][32] This also applies to most countries' national competitions.[13] At lower levels of the game, where use of a computer cannot always be guaranteed, the Standard Edition is used.[13] 2009 - Twenty20 updatesIn June 2009, it was reported that the D/L method would be reviewed for the Twenty20 format after its appropriateness was questioned in the quickest version of the game. Lewis was quoted admitting that "Certainly, people have suggested that we need to look very carefully and see whether in fact the numbers in our formula are totally appropriate for the Twenty20 game."[33] 2015 – Becomes DLSFor the 2015 World Cup, the ICC implemented the Duckworth–Lewis–Stern formula, which included work by the new custodian of the method, Professor Steven Stern, from the Department of Statistics at Queensland University of Technology. These changes recognised that teams need to start out with a higher scoring rate when chasing high targets rather than keep wickets in hand.[34] Target score calculationsUsing the notation of the ICC Playing Handbook,[32] the team that bats first is called Team 1, their final score is called S, the total resources available to Team 1 for their innings is called R1, the team that bats second is called Team 2, and the total resources available to Team 2 for their innings is called R2.

Step 1. Find the batting resources available to each teamAfter each reduction in overs, the new total batting resources available to the two teams are found, using figures for the total amount of batting resources remaining for any combination of overs and wickets. While the process for converting these resources remaining figures into total resource available figures is the same in the two Editions, this can be done manually in the Standard Edition, as the resource remaining figures are published in a reference table.[26] However, the resource remaining figures used in the Professional Edition are not publicly available,[13] so a computer must be used which has the software loaded.

These are just the different ways of having one interruption. With multiple interruptions possible, it may seem like finding the total resource percentage requires a different calculation for each different scenario. However, the formula is actually the same each time − it's just that different scenarios, with more or less interruptions and restarts, need to use more or less of the same formula. The total resources available to a team are given by:[26]

which can alternatively be written as:

Each time there's an interruption or a restart after an interruption, the resource remaining percentages at those times (obtained from a reference table for the Standard Edition, or from a computer for the Professional Edition) can be entered into the formula, with the rest left blank. Note that a delay at the start of an innings counts as the 1st interruption. Step 2. Convert the two teams' batting resources into Team 2's target scoreStandard Edition

G50 G50 is the average score expected from the team batting first in an uninterrupted 50 overs-per-innings match. This will vary with the level of competition and over time. The annual ICC Playing Handbook[32] gives the values of G50 to be used each year when the D/L Standard Edition is applied:

Duckworth and Lewis wrote:

Professional Edition

Example Standard Edition Target score calculationsAs the resource percentages used in the Professional Edition are not publicly available, it is difficult to give examples of the D/L calculation for the Professional Edition. Therefore, examples are given from when the Standard Edition was widely used, which was up to early 2004. Reduced target: Team 1's innings completed; Team 2's innings delayed (resources lost at start of innings)

On 18 May 2003, Lancashire played Hampshire in the 2003 ECB National League.[37][38][39] Rain before play reduced the match to 30 overs each. Lancashire batted first and scored 231–4 from their 30 overs. Before Hampshire began their innings, it was further reduced to 28 overs.

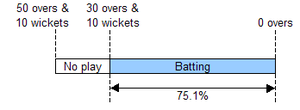

Hampshire's target was therefore 221 to win (in 28 overs), or 220 to tie. They were all out for 150, giving Lancashire victory by 220 − 150 = 70 runs. If Hampshire's target had been set by the Average Run Rate method (simply in proportion to the reduction in overs), their par score would have been 231 x 28/30 = 215.6, giving 216 to win or 215 to tie. While this would have kept the required run rate the same as Lancashire achieved (7.7 runs per over), this would have given an unfair advantage to Hampshire as it's easier to achieve and maintain a run rate for a shorter period. Increasing Hampshire's target from 216 overcomes this flaw. As Lancashire's innings was interrupted once (before it started), and then restarted, their resource can be found from the general formula above as follows (Hampshire's is similar): Total resources = 100% − Resources remaining at 1st interruption + Resources remaining at 1st restart = 100% − 100% + 75.1% = 75.1%.

Reduced target: Team 1's innings completed; Team 2's innings cut short (resources lost at end of innings)

On 3 March 2003, Sri Lanka played South Africa in World Cup Pool B.[40][41] Sri Lanka batted first and scored 268–9 from their 50 overs. Chasing a target of 269, South Africa had reached 229–6 from 45 overs when play was abandoned.

Therefore, South Africa's retrospective target from their 45 overs was 230 runs to win, or 229 to tie. In the event, as they had scored exactly 229, the match was declared a tie. South Africa scored no runs off the very last ball. If play had been abandoned without that ball having been bowled, the resource available to South Africa at the abandonment would have been 14.7%, giving them a par score of 228.6, and hence victory. As South Africa's innings was interrupted once (and not restarted), their resource is given by the general formula above as follows: Total resources available = 100% − Resources remaining at 1st interruption = 100% − 14.3% = 85.7%. Reduced target: Team 1's innings completed; Team 2's innings interrupted (resources lost in middle of innings)On 16 February 2003, New South Wales played South Australia in the ING Cup.[42][43] New South Wales batted first and scored 273 all out (from 49.4 overs). Chasing a target of 274, rain interrupted play when South Australia had reached 70–2 from 19 overs, and at the restart their innings was reduced to 36 overs (i.e. 17 remaining).

South Australia's new target was therefore 214 to win (in 36 overs), or 213 to tie. In the event, they were all out for 174, so New South Wales won by 213 − 174 = 39 runs. As South Australia's innings was interrupted once and restarted once, their resource is given by the general formula above as follows: Total resources available = 100% − Resources remaining at 1st interruption + Resources remaining at 1st restart = 100% − 68.6% + 46.7% = 78.1%. Increased target: Team 1's innings cut short (resources lost at end of innings); Team 2's innings completedOn 25 January 2001, West Indies played Zimbabwe.[44][45] West Indies batted first and had reached 235–6 from 47 overs (of a scheduled 50) when rain halted play for two hours. At the restart, both innings were reduced to 47 overs, i.e. West Indies' innings was closed immediately, and Zimbabwe began their innings.

Zimbabwe's target was therefore 253 to win (in 47 overs), or 252 to tie. It is fair that their target was increased, even though they had the same number of overs to bat as West Indies, as West Indies would have batted more aggressively in their last few overs, and scored more runs, if they had known that their innings would be cut short at 47 overs. Zimbabwe were all out for 175, giving West Indies victory by 252 − 175 = 77 runs. These resource percentages are the ones which were in use back in 2001, before the 2002 revision, and so do not match the currently used percentages for the Standard Edition, which are slightly different. Also, the formula for Zimbabwe's par score comes from the Standard Edition of D/L, which was used at the time. Currently the Professional Edition is used, which has a different formula when R2>R1. The formula required Zimbabwe to match West Indies' performance with their overlapping 89.8% of resource (i.e. score 235 runs), and achieve average performance with their extra 97.4% − 89.8% = 7.6% of resource (i.e. score 7.6% of G50 (225 at the time) = 17.1 runs). As West Indies' innings was interrupted once (and not restarted), their resource is given by the general formula above as follows: Total resources available = 100% − Resources remaining at 1st interruption = 100% − 10.2% = 89.8%.

Increased target: Multiple interruptions in Team 1's innings (resources lost in middle of innings); Team 2's innings completedOn 20 February 2003, Australia played Netherlands in the 2003 Cricket World Cup Pool A.[46][47][48][49] Rain before play reduced the match to 47 overs each, and Australia batted first.

The Netherlands' target was therefore 198 to win (in 36 overs), or 197 to tie. It is fair that their target was increased, even though they had the same number of overs to bat as Australia, as Australia would have batted less conservatively in their first 28 overs, and scored more runs at the expense of more wickets, if they had known that their innings would only be 36 overs long. Increasing the Netherlands' target score neutralises the injustice done to Australia when they were denied some of the overs to bat they thought they would get. The Netherlands were all out for 122, giving Australia victory by 197 − 122 = 75 runs. This formula for Netherlands' par score comes from the Standard Edition of D/L, which was used at the time. Currently the Professional Edition is used, which has a different formula when R2>R1. The formula required Netherlands to match Australia's performance with their overlapping 72.6% of resource (i.e. score 170 runs), and achieve average performance with their extra 84.1% − 72.6% = 11.5% of resource (i.e. score 11.5% of G50 (235 at the time) = 27.025 runs). After the match there were reports in the media[47] that Australia had batted conservatively in their final 8 overs after the final restart, to avoid losing wickets rather than maximising their numbers of runs, in belief that this would further increase the Netherlands' par score. However, if this is true, this belief was mistaken, in the same way that conserving wickets rather than maximising runs in the final 8 overs of a full 50-over innings would be a mistake. At that point the amount of resource available to each team was fixed (as long as there were no further rain interruptions), so the only undetermined number in the formula for Netherlands' par score was Australia's final score, so they should have tried to maximise this. As Australia's innings was interrupted three times (once before it started) and restarted three times, their resource is given by the general formula above as follows: Total resources available = 100% − Resources remaining at 1st interruption + Resources remaining at 1st restart − Resources remaining at 2nd interruption + Resources remaining at 2nd restart − Resources remaining at 3rd interruption + Resources remaining at 3rd restart = 100% − 100% + 97.1% − 55.8% + 50.5% − 44.7% + 25.5% = 72.6%. In-game strategyDuring team 1's inningsStrategy for team 1During Team 1's innings, the target score calculations (as described above), have not yet been made. The objective of the team batting first is to maximise the target score which will be calculated for the team batting second, which (in the Professional Edition) will be determined by the formula:

For these three terms:

If there will not be any future interruptions to Team 1's innings, then the amount of resource available to them is now fixed (whether there have been interruptions so far or not), so the only thing Team 1 can do to increase Team 2's target is increase their own score, ignoring how many wickets they lose (as in a normal unaffected match). However, if there will be future interruptions to Team 1's innings, then an alternative strategy to scoring more runs is minimising the amount of resource they use before the coming interruption (i.e. preserving wickets). While the best overall strategy is obviously to both score more runs and preserve resources, if a choice has to be made between the two, sometimes preserving wickets at the expense of scoring runs ('conservative' batting) is a more effective way of increasing Team 2's target, and sometimes the reverse ('aggressive' batting) is true.

For example, suppose Team 1 has been batting without interruptions, but thinks the innings will be cut short at 40 overs, i.e. with 10 overs left. (Then Team 2 will have 40 overs to bat, so Team 2's resource will be 89.3%.) Team 1 thinks by batting conservatively it can reach 200–6, or by batting aggressively it can reach 220–8:

Therefore, in this case, the conservative strategy achieves a higher target for Team 2.

However, suppose instead that the difference between the two strategies is scoring 200–2 or 220–4:

In this case, the aggressive strategy is better. Therefore, the best batting strategy for Team 1 ahead of a coming interruption is not always the same, but varies with the facts of the match situation to date (runs scored, wickets lost, overs used, and whether there have been interruptions), and also with the opinions about what will happen with each strategy (how many further runs will be scored, further wickets will be lost, and further overs will be used? How likely are the coming interruptions, when will they happen, and how long will they last – will Team 1's innings be restarted?). This example shows just two possible batting strategies, but in reality there could be a range of others, e.g. 'neutral', 'semi-aggressive', 'super-aggressive', or timewasting to minimise the amount of resource used by slowing the over rate. Finding which strategy is the best can only be found by inputting the facts and one's opinions into the calculations and seeing what emerges. Of course, a chosen strategy may backfire. For example, if Team 1 chooses to bat conservatively, Team 2 may see this and decide to attack (rather than focus on saving runs), and Team 1 may both fail to score many more runs and lose wickets. If there have already been interruptions to Team 1's innings, the calculation of total resource they use will be more complicated than this example. Strategy for team 2During Team 1's innings, Team 2's objective is to minimise the target score they will be set. This is achieved by minimising Team 1's score, or (as above), if there will be future interruptions to Team 1's innings, alternatively by maximising the resource used by Team 1 (i.e. wickets lost or overs bowled) before that happens. Team 2 can vary their bowling strategy (between conservative and aggressive) to try to achieve either of these objectives, so this means doing the same calculations as above, inputting their opinions of future runs conceded, wickets taken and overs bowled in each bowling strategy, to see which one is best. Also, Team 2 can encourage Team 1 to bat particularly conservatively or aggressively (e.g. through field settings). During team 2's inningsA target (from a given number of overs) is set for Team 2 at the start of its innings. If there will not be any future interruptions, then both sides can play to a finish in the normal way. However, if there are likely to be interruptions to Team 2's innings, then Team 2 will aim to keep itself ahead of the D/L par score, and Team 1 will aim to keep them behind it. This is because, if a match is abandoned before the given number of overs is complete, Team 2 is declared the winner if they're ahead of the par score, and Team 1 is declared the winner if Team 2 are behind the par score. A tie is declared if Team 2 are exactly on the par score. (This is provided a minimum number of overs has been bowled in Team 2's innings.) The par score increases with every ball bowled and every wicket lost, as the amount of resource used increases. As an example, in the 2003 Cricket World Cup Final Australia batted first and scored 359 from 50 overs. As Australia completed their 50 overs, their total resources used R1=100%, so India's par score throughout their innings was: 359 x R2/100%, where R2 is the amount of resource used to that point. As shown in the first line of the table below, after 9 overs India were 57-1, and 41 overs and 9 wickets remaining equates to 85.3% of resources, so 100% − 85.3% = 14.7% had been used. India's par score after 9 overs was therefore 359 x 14.7%/100% = 52.773, which is rounded down to 52. During the six balls of the 10th over India scored 0, 0, 0, 1 (from a no ball), loss of wicket, 0.[50] At the start of the over India were ahead of the par score, but the loss of the wicket caused their par score to jump from 55 to 79, which put them behind the par score.

Other usesThere are uses of the D/L method other than finding the current official final target score for the team batting second in a match that has already been reduced by the weather. Ball-by-ball par score  During the second team's innings, the number of runs a chasing side would expect to have scored on average with this number of overs used and wickets lost, if they were going to successfully match the first team's score, called the D/L par score, may be shown on a computer printout, the scoreboard and/or TV alongside the actual score, and updated after every ball. This can happen in matches which look like they're about to be shortened by the weather, and so D/L is about to be brought into play, or even in matches completely unaffected by the weather. This is:

Net run rate calculationIt has been suggested that when a side batting second successfully completes the run chase, the D/L method could be used to predict how many runs they would have scored with a full innings (i.e. 50 overs in a One Day International), and use this prediction in the net run rate calculation.[53] This suggestion is in response to the criticisms of NRR that it does not take into account wickets lost, and that it unfairly penalises teams which bat second and win, as those innings are shorter and therefore have less weight in the NRR calculation than other innings which go the full distance. CriticismThe D/L method has been criticised on the grounds that wickets are a much more heavily weighted resource than overs, leading to the suggestion that if teams are chasing large targets and there is the prospect of rain, a winning strategy could be to not lose wickets and score at what would seem to be a "losing" rate (e.g. if the required rate was 6.1, it could be enough to score at 4.75 an over for the first 20–25 overs).[54] The 2015 update to DLS recognised this flaw, and changed the rate at which teams needed to score at the start of the second innings in response to a large first innings. Another criticism is that the D/L method does not account for changes in proportion of the innings for which field restrictions are in place compared to a completed match.[55] More recent efforts have used ball-by-ball ODI databases of actually completed matches to evaluate the accuracy of the method.[56] Those efforts have concluded that the DLS par score can have accuracies as low as 50 to 60% at predicting the eventual winner of the match when the team batting second bats between 20 and 24 overs and loses between 0 and 2 wickets. More common informal criticism from cricket fans and journalists of the D/L method is that it is unduly complex and can be misunderstood.[57][58] For example, in a one-day match against England on 20 March 2009, the West Indies coach (John Dyson) called his players in for bad light, believing that his team would win by one run under the D/L method, but not realising that the loss of a wicket with the last ball had altered the Duckworth–Lewis score. In fact Javagal Srinath, the match referee, confirmed that the West Indies were two runs short of their target, giving the victory to England. Concerns have also been raised as to its suitability for Twenty20 matches, where a high scoring over can drastically alter the situation of the game, and variability of the run-rate is higher over matches with a shorter number of overs.[59] Cultural influenceThe Duckworth Lewis Method is the name of a pop group, formed by Neil Hannon of The Divine Comedy and Thomas Walsh of Pugwash. Their first release was an eponymous album, which features cricket-themed songs.[60][61] Notes

References

Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||