|

Drayton House

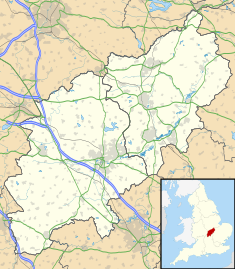

Drayton House is a Grade I listed[1] country house of many periods[2] 1 mile (1.6 km) south-west of the village of Lowick, Northamptonshire, England. Described as Northamptonshire's most impressive medieval mansion by Nikolaus Pevsner,[3] "one of the best-kept secrets of the English country house world" by architectural historian Gervase Jackson-Stops,[4] and (affectionately) "a most venerable heap of ugliness, with many curious bits" by Horace Walpole,[5] the house is generally held to have been begun in 1328.[6] There have been changes to the house in each century since, including works recorded by John Webb,[1][7][8] Isaac Rowe,[1] William Talman,[1] Jean Tijou,[7][9] Tilleman Bobart,[7] Henry Wise,[7] Gerard Lanscroon,[1][9] John Van Nost,[7] William Rhodes,[1] Alexander Roos,[1] George Devey[1] and John Alfred Gotch.[1] It sits in a park of about 200 acres known as Drayton Park.[10] It has passed only by inheritance since it was last sold in 1361,[11] although this was itself an arrangement within extended family[12] who had been there for nearly 300 years already.[13] It is currently owned by the Stopford Sackville family[14][15] and has been open by prior written appointment.[2][15][16][17][18][19][20] History The de Veres, later de DraytonsAubrey de Vere I participated in the Norman conquest of England and after Geoffrey de Montbray, Bishop of Coutances, forfeited it,[10] he may have been awarded the manor of Drayton near Northampton,[21] or it may have been awarded to his son, Aubrey de Vere II.[10] Aubrey II was made Great Chamberlain by Henry I in 1133 and died in a riot in London in 1141. Whilst Aubrey III, his eldest son, eventually rose to become Earl of Oxford in 1156,[21] Drayton passed to his younger son, Robert.[10] Robert married twice, second to Maud de Furnell, mother of Henry, to whom Drayton passed on his death.[10] In the early thirteenth century, after inheriting Drayton after his father's death in 1193-4, his son, Sir Walter de Vere, perhaps dropped the "de Vere" family name, and assumed the surname "Drayton", taken from the village,[6][22][23] although this may also have been Walter's son, Henry.[10] On Sir Walter's death in 1210-11, the house passed to Henry, later Sir Henry, and upon Sir Henry's death in 1253, to Sir Henry's thirty-year-old[10] son, Baldwin, who died in 1278. Baldwin passed the estate to his son John, who is held by some sources to have built the present "crypt"[22] and died in 1291.[10] Although still a minor 8 years after his father's death in 1299, Sir Simon de Drayton would go on to success, being member of parliament for Northamptonshire several times between 1320 and 1347,[10] and likely began construction of the house present today in 1328,[6] when he received a licence to crenellate.[22][24] On his widow's death in 1359, it passed briefly to his son, John, before John quickly passed it to his son, Baldwin.[10] However, it was soon purchased by Sir Henry Green in 1361[11][25] or 1362.[10] This purchase was a somewhat obscure arrangement[12] in which Sir Henry's second son, also Henry, would have the estate instead of John's son, who was Sir Henry's nephew through his wife, Katherine.[10] The GreensThe first Sir Henry Green, of Boughton,[Note 1] was Chief Justice between 1361 and 1365. On his death in 1370,[10] Drayton passed to his younger son, who was described in a later family genealogy as "the delight and hopes of his old father".[10] The second Henry was a favourite of Richard II, consequently being executed in 1399 for his support for Richard by Henry Bolingbroke, later King of England.[6] Nonetheless, soon after his father's beheading, Ralph Green was returned to his father's estates, including Drayton. It eventually passed to Ralph's nephew, another Henry Green, who was High Sheriff through the Wars of the Roses, reportedly acting impartially and thus saving his landholdings—at that time "one of the most considerable Estates ... in the possession of any Gentlemen in the Kingdom of England".[26] Upon his death in 1467, he passed the house, via his only child Constance, to John Stafford, a son of the Duke of Buckingham. The Staffords John Stafford would become Earl of Wiltshire in 1470, a reward for fighting for the Yorkist cause. For these allegiances, he would be prevented from attending parliament later that year, as Henry VI, from the House of Lancaster, had returned to the throne. Despite his father's loyalties, John's son Edward is often called a Lancastrian, by consequence of his support for Henry VII, fighting for him at the Battle of Blackheath and entertaining him at the house in 1498.[6][26] Returning ill from Blackheath, Edward was without heirs, and it would seem he was initially keen for his wife, Margaret, daughter of the Lord Lisle, to have Drayton for life. However, Margaret was not happy with this will, wanting the manor of Warminster. It would seem that Edward thenceforth wished the Earl of Shrewsbury, a cousin, to have Drayton, not wanting his other cousins, women and descendants of the original Sir Walter de Drayton, to inherit.[27] However, Sir John Mordaunt (d. 1506), the serjeant-at-law present at Wiltshire's death, had obtained the wardship of the female cousins, and wished for the eldest, Elizabeth, to marry his son, John (d. 1562). Thus, John (d. 1506) seems to have ensured that Wiltshire's will was in his son's favour.[28] Nonetheless, from Edward's death in 1499, there was a 16-year-long period during which the heir to the house was disputed,[29] before being resolved to in John Mordaunt's (d. 1562) favour. The Mordaunts The Mordaunts were originally from Turvey, Bedfordshire.[8] Upon Elizabeth Mordaunt (née Vere) inheriting in 1515, John Mordaunt (d. 1506) had already died, and his son John (d. 1562) already had an heir, himself also called John. It has been suggested that Henry VIII was involved in ending the dispute favourably for John (d. 1562), given their amicable early relationship.[28] Indeed, John (d.1562) rose to the Privy Council, was created Lord Mordaunt in 1532,[6] and had managed to cheaply purchase the marriage of Ella Fitzlewis, who had a large fortune, from the King for his son. However, this good relationship was not to last, as he grew increasingly unhappy with the dissolution of the monasteries, and so withdrew from court life to the house. His enemies reportedly encouraged King Henry to force him into an agreement much akin to, and as unfavourable as, the deal into which Thomas Cranmer had been forced over Knole. Henry died before they could realise their goal, and John lived through the turbulent times of Mary I and Edward VI,[28] dying in 1561, in the reign of Elizabeth I.[10] His son, John (d. 1571), therefore inherited the house and the title, becoming 2nd Baron Mordaunt. However, he only enjoyed the house for 9 years, before passing it to his son, Lewis (1538–1601). Lewis, whilst not a member of the court, lived in opulence and greatly altered and enlarged Drayton.[6][30]

The disparity between his lifestyle and situation required Lewis to sell both the FitzLewis estates of his mother and the Latimer estates of his great-grandmother.[31] Lewis was also one of the judges present at the trial of Mary, Queen of Scots at Fotheringhay, although sympathetic to Catholicism.[31] Lewis married Elizabeth, granddaughter of Thomas Darcy, 1st Baron Darcy de Darcy[32] and had a son, Henry (1568–1610),[6] who inherited the house on his death in 1601. From 3 August 1605, Henry entertained James VI and I and Anne of Denmark at Drayton for three days with musicians and singers.[31][33] According to the queen's secretary, William Fowler, the guests included the Earls of Worcester, Devonshire, Northampton, Sussex, and Salisbury, and the Duke of Lennox.[34] However, later there were rumours that there had been a plot to kill King James at Drayton during this visit during a masque entertainment. Two Gunpowder Plot conspirators Ambrose Rookwood and Thomas Winter had been at Drayton on the day before King James arrived.[35][36] Henry Mordaunt (1568–1610) is known to have concealed priests at Drayton, with the house retaining one priest hole,[37] and was heavily suspected of involvement in the Gunpowder Plot of November 1605.[6] Robert Keyes – sometimes quoted as the keeper of his Turvey house,[31] and other times as the husband of the governess of Henry's children[38] – was a key conspirator and hid at Drayton after the plot's demise.[39] For his involvement, Henry Mordaunt was fined £666 13s 4d[6] and imprisoned in the Tower, with some sources even reporting that he died there in 1608.[31][37] Either way, he died before his successor and son, John (1599–1643), was of maturity. John was taken from Catholic relations and raised by George Abbot, Archbishop of Canterbury, from 1611. Well regarded, he was called "the Star of the University" whilst at Oxford, and thus he caught James I's eye, so meaning he was relieved from the remaining £10,000 fine placed on his father.[31] However, soon the King met George Villiers, and all chance at being royal favourite was lost. He remained on good terms with Charles, then Prince of Wales, playing a key role in his investiture as Prince of Wales. Therefore, he secured a good marriage to Elizabeth, daughter of Lord Howard of Effingham, and was created Earl of Peterborough in 1628. Initially, along with his two sons, he was a Royalist in the Civil War. In a turn of events, however, his wife, a "great Republican", persuaded him to be a Roundhead[40][41] and he became a General of Ordnance in the Parliamentary army.[6] Henry Mordaunt, 2nd Earl of Peterborough John Mordaunt, 1st Viscount Mordaunt, 1739, by John Alexander John's son and successor, Henry (1623–1697), was only 17 when he inherited. This situation was exploited by his mother, who ensured that much of John's estate was left to her as jointure, in a settlement drawn up on his deathbed. This left Henry with "but a very small Estate to live upon when he became Earle [sic]," believing he had inherited only the Turvey estate. John executed a deed beforehand which meant that Henry inherited all his estate, but this deed was concealed from Henry by his mother. It was not until 1669, when the original deed was found, that Henry was able to discover this and so take his mother to court, regaining ownership of his estates.[42] Henry quickly returned to being a Royalist in the Civil War,[40] and did not quickly give up this cause. Initially exhausting his wife's, a daughter of the Earl of Thomond, dowry in fines, he was later forced to compound for his estates[6] in 1646.[41][43] Regardless, he was involved in the Second English Civil War with the Earl of Holland, of whom a full-length portrait by Mytens still hangs in the Dining Room.[41][44][45] However, after being compounded a second time in 1649,[41] he retreated to Drayton, his mother—despite her sympathetic allegiances—retiring to Reigate after harassment in 1650 by Parliamentarians, allowing him to negotiate to take on the lease.[46] This was not the case for his brother, John (1627–1675), who continued in his convictions and was saved by a single vote from execution for his role in the 1658 conspiracy.[47] This resulted in John's (1627–1675) elevation to the peerage as Viscount Mordaunt of Avalon and Baron Mordaunt of Reigate in 1659. Despite Henry's (1623–1697) position as elder son, on his mother's death in 1671, he did not gain her Reigate estates as he had expected to, the estate passing instead to his brother (whose peerage was "of Reigate").[48] In addition, John seems to have been involved in their mother's concealing of their father's deeds from Henry.[40] This resulted in litigation between the two brothers, which Henry (1623–1697) lost, and so he was left a thousand pounds per year less well off.[48] Therefore, to increase funds, Henry (1623–1697) accepted the position of Governor of Tangier from 1661 to 1663, although he resigned it swiftly for a pension which was worth that thousand pounds per year.[49] He was later Ambassador to France, First Gentleman of the Bedchamber, and Groom of the Stole to the Duke of York.[6] He was also chosen to arrange the marriage of Mary of Modena with the Duke of York. During this time, he also worked with his chaplain, “Mr Rans”,[50] to produce a family history, Succinct Genealogies, published in 1685,[6] under the pseudonym "Halstead".[51] Some sources hold that a "Robert Halstead" was indeed his chaplain at this time.[6][52]  By this time, his nephew Charles had succeeded John (1627–1675) as Viscount Mordaunt. A Whig, Charles was suspected in the Rye House Plot, moving to Holland, reportedly being the first person to encourage William of Orange "to undertake the business of England."[53] Through the success of the Glorious Revolution, he returned to England and was created Earl of Monmouth. Meanwhile, Henry (1623–1697) had become a suspect in the Popish Plot, and openly admitted to his religious conversion to Catholicism (persuaded by James II) in 1687. This led to his impeachment for high treason[53] in 1688.[6] Some sources state he was imprisoned for this, but released on bail in 1690.[6] Others state that he was just confined to his home until his death in 1697.[53] After Henry's death, the Peterborough Earldom and older Mordaunt Barony split due to different remainders. Henry had ensured that the Drayton would pass with the barony to Mary Howard (née Mordaunt), Duchess of Norfolk, instead of with the earldom to his nephew, Charles.[6] It would seem this was more out of spite for the Reigate side of the family, the split between the two never having been resolved, than for his daughter's merits. Charles would dispute this descent for the next twenty years.[54]  Mary had been married to Henry, Earl of Arundel in 1677. Within seven years, he had succeeded as Duke of Norfolk.[55] However, the marriage was not to last, and the Duke spent over half of his time in the marriage attempting to divorce Mary. It would seem that Mary quickly took a fancy to Sir John Germain, 1st Baronet (1650–1718), described as "always a distinguished Favourite of the other Sex."[56] From soon after, in 1685,[57] she no longer apparently lived with the Duke, and her relationship with Sir John was well-known.[56] In April 1700, after the Duke, who openly had a mistress himself,[58] had already tried twice (and been twice denied by William III), a divorce was allowed[59] by Parliament.[58] Mary married her lover after the Duke's death in 1701.[60] Nevertheless, she continued to use both the arms and style of "Duchess of Norfolk".[11] On her death in 1705, the house passed to her new husband,[6] not without dispute by her cousin Charles,[61] who unsuccessfully tried to gain the house in the courts in both 1705 and 1710. Thus, there was hostility between Sir John and the Earl, which may have made its way into later descriptions of Sir John.[54] The Germains Sir John was a soldier and prominent member of the court of William III. His mother was herself "very handsome" and was supposedly the wife of a private soldier in William II, Prince of Orange's Life Guards.[56] However, she was rumoured to be a mistress of William II, so making Sir John the illegitimate half-brother of William III.[6][11] Some saw William III's positive attitude[57] towards Sir John as further evidence of this, especially when considering his personality; Horace Walpole, a frequent visitor throughout the 1760s,[5] described Sir John as having "defective morals,"[59] and yet the King twice influenced the House of Lords to not allow a divorce between the Duke and Duchess of Norfolk, and then gave John a baronetcy in 1698.[59] Others stressed that he was a skilled soldier anyway, accompanying William III during the 1688 Glorious Revolution and later conflicts. Despite such skill, no records remain of the feats he may have performed.[59]  On his death in 1718, he passed the house on to his much younger second wife,[62] who he married in 1706,[54] Lady Elizabeth (Betty) Germain (née Berkeley) (1680–1769). Betty and Sir John had had three children, but all died in infancy. Thus, on his death bed, Sir John reportedly encouraged her to remarry—this time not to an old man—and secure an heir for the estate, and if this was not possible, to pass it on to a younger son of his "Friend, the Duchess of Dorset."[54] Betty maintained the house as Sir John had left it[63] and did not remarry. She was often at Knole, the Kent country house of the Dukes of Dorset, and the Dorsets similarly visited her frequently, too,[54] with her spending every summer after her husband's death at Drayton.[61] Indeed, Lord George Sackville (1716–1785) went straight to Drayton after his wedding to visit Betty, a close friend.[54] Therefore, true to Sir John's wishes, she gave the house to George, her cousin[6] and a son of the Duchess of Dorset, on her death.[54] The Sackvilles Thus the house passed to the Sackville family, although George changed his name to Germain upon inheriting. With George already established at Stoneland Lodge, Drayton was now only occasionally in residential use.[64] However, this did not stop him from undertaking refurbishments to catch up with the 50-year backlog, although these were curtailed by his becoming Secretary of State for the Colonies and so no longer being able to reside at Drayton for long periods, being needed in London.[65] He was made Viscount Sackville in 1782.[64] Upon his death in 1785, his son, Charles, was still a minor. Charles would go on to inherit the Dorset Dukedom in 1815, when his cousin was killed in Ireland. However, he had a keen interest in horse racing and was not often at Drayton, at times even letting it to his brother, George.[64] It was through his brother's line that Drayton would descend on his death (which resulted in the extinction of the Dukedom and Viscountcy) in 1843, passing to George's daughter, Caroline Harriet Sackville,[66][67] and her husband, William Bruce Stopford,[45][68] from 1870[67] Stopford-Sackville.[66] It has continued to pass through her descendants since,[64] passing to their son, Sackville Stopford-Sackville, member of parliament for North Northamptonshire 1867–80, and then again 1900–1906. When he died without issue[67] in 1926, his brother had been dead for twenty years already,[69] and his two eldest nephews had both died in the war.[70] Therefore, the house passed to his youngest[71] nephew, Nigel Victor Stopford-Sackville,[10][69] who would go on to be an officer in the army[72] and write a "short historical account of ownership, architecture, and contents" of the house.[73][74] In 1958, there was some discussion about leaving the house to the National Trust, however this did not occur.[75] Nigel's son[citation needed], Lionel Geoffrey[76] Stopford Sackville, inherited the house on his father's death in 1972[72] and moved to live at Drayton in 1973, commencing a series of restorations over the next two decades.[77] It is now owned by his son, Charles Lionel[78] Stopford Sackville.[79] HouseHistoric developmentAlthough most commonly held to have been begun by Sir Simon de Drayton upon gaining a licence to crenellate in 1328,[6] some have also claimed that the undercroft to the original solar of the house predates this and is from the reign of Edward I.[22][80] If this were true, then the earliest parts of the current house would have been built by Sir Simon's father, Sir John. Regardless, by the end of the time of Sir Simon (the mid-14th century) there was almost certainly a house, similar in original layout to Penshurst, with a defensive wall and moat, still partly extant, around it. This moat may have used sluices, given the slope from north to south, and it is possible that the moat predated the house built at the time, on account of the angle of the western part of the South wall. The layout would have been centred around a hall which, given the current hall's 6 feet (1.8 m) thick walls and the western position of the hall's current entrance doorway (in the former position of a screens passage), lives on in the masonry of the current hall.[24] This hall was to the west of the undercroft, and likely had windows in both its north and south walls; doorways in the screens passage to the pantry & buttery and kitchen; and an entrance to a stair turret to the solar, which extended slightly north of the hall, in its north-east corner. The kitchen was probably detached from the rest of the house, in the position of (if not remaining partially in the masonry of) the present kitchen. The house covered the current main courtyard, likely including rooms along the South wall,[22] which retains bays from the early 14th century.[1] Writing in a 1540 visit, John Leland believed most of the house he saw to have been built by Henry Green (d. 1399).[citation needed] However, more modern authors have attributed the house's enlargement to this Henry's great-nephew, another Henry Green. Whilst little 15th century masonry remains prominent, John Alfred Gotch's survey of the house identified significant areas from that period. Important examples include the house's two characteristic towers, the hall's north porch, and two further projections to the north, currently housing the Stone and Oak Stairs. The space between the porch and these projections was later filled in.[81] Many of the later medieval alterations are believed to have been at the behest of the 2nd Earl of Wiltshire.[6] Through the evidence from witnesses involved in the inheritance dispute following the Earl's death, the presence of a "Chapell [sic] chamber", "Great Chamber", and "high Chamber" where the "Erle [sic] lay sick" can be inferred. Furthermore, there is mention of a "Moote" -- proof of an extant moat in 1497.[22][27]  There were major late 16th-century alterations and additions under the 3rd Lord Mordaunt, who was described as a "Builder" by Halstead. A significant addition was the North wing, dated 1584, which includes an antiquarian cellar in its basement, similar plan but not stylistically to the older undercroft to its South. He also updated older areas, including the Chapel Room—through which the gallery of the present chapel is reached—which retains panelling and an overmantel from the period,[28] and the Oak Staircase.[30] Otherwise, most of the interiors from this time have been lost, with wainscot from the period being reused haphazardly throughout the house's lesser rooms. Smaller external modifications were carried out to the West wing of the main courtyard, where windows from this period remain. It is conjectured that much of the East elevation had similar windows, before later alterations, when the mullioned windows were replaced with sash windows. Some of these replacement sashes were later returned to their original state.[28] Despite having to compound for his estates, the 2nd Earl of Peterborough appears to have engaged Inigo Jones's associate John Webb. There are two drawings of mantelpieces in a collection of their drawings formerly owned by the Dukes of Devonshire and later by the Royal Institute of British Architects, signed by Webb and dated 1653, one "For ye Bed chamber in ye ground Story of Drayton," recognisable as that of the State bedroom (although the lower half has been modified), and another for "the withdrawing roome to the Bedchamber in the lower Story at Drayton." This room is now known as the Blue Drawing Room, but the present mantelpiece is characteristic of the late 17th century, suggesting his plans for the room were not enacted. Given similarity to work he carried out at Thorpe, it is likely that he worked on most rooms in the north of the North wing, which contain doorcases in his style. A room of particular interest is the closet to the east of the State bedroom, which contains cut lacquer panels with scenes of people in the gardens outside houses. Despite the dating of the drawings to 1653, it is unlikely that Webb carried out much work until after the Restoration, and it is unlikely he did any work at Drayton after the Glorious Revolution.[41] The house underwent transformation during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, much in the rare English Baroque. There is a unique spiral cantilever oak staircase dating from around 1680 and an embroidered State Bed from 1700. It is built of squared coursed limestone and limestone ashlar with lead and Collyweston stone slate roofs. In a 1770 inventory, the house contained two paintings of animals attributed to Francis Barlow.[82] After passing to the Sackville family, two rooms were redecorated in the Adam style.[16][64] Pevsner considered these to be the best examples of the style in Northamptonshire.[83] Perambulation and contents

Park and gardensHistoric developmentA park has existed at Drayton since at least when Sir Simon de Drayton received a licence to empark 30 acres in 1327.[10] The similarity between the balusters of the 16th-century Oak Staircase and those of both Drayton's eastern garden terrace and those of the 16th-century[84] walls at Montacute has been cited as evidence that the 3rd Lord Mordaunt laid out the foundations for the current gardens. A remaining sundial with the arms of Darcy (the family of the 3rd Lord's family) and Mordaunt has been used as further evidence of this.[31] During the late 19th century the Park was the host location for an early Victorian era tennis tournament called North Northamptonshire LTC Tournament[85] organised by North Northamptonshire Lawn Tennis Club that was held between 1880 and 1883.[citation needed] DescriptionThe park, known as Drayton Park, now stretches to about 200 acres,[10] and has been described as "vast".[86] In popular cultureThe house and gardens were used as the titular estate in Emerald Fennell's 2023 film Saltburn.[87] Since the release of the film, due largely to a popular video on the social media app TikTok, the home has been "plagued by trespassers and influencers" according to the owner.[88] It was also used as a location in Steven Knight's 2024 miniseries The Veil. See also

Notes

References

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Drayton House. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||