|

Downtown Hudson Tubes

KML is from Wikidata

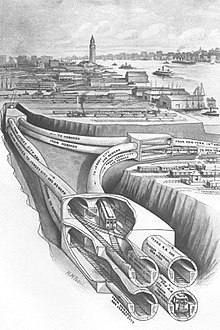

The Downtown Hudson Tubes (formerly the Cortlandt Street Tunnel[2]) are a pair of tunnels that carry PATH trains under the Hudson River in the United States, between New York City to the east and Jersey City, New Jersey, to the west. The tunnels run between the World Trade Center station on the New York side and the Exchange Place station on the New Jersey side. PATH operates two services through the Downtown Tubes, Newark–World Trade Center and Hoboken–World Trade Center. The former normally operates 24/7, while the latter only operates on weekdays.[3] DescriptionThe Downtown Hudson Tubes use a roughly east-southeast to west-northwest path under the Hudson River, connecting Manhattan in the east with Jersey City in the west. Each track is located in its own tube,[1] which enables better ventilation by the so-called piston effect. When a train passes through the tunnel it pushes out the air in front of it toward the closest ventilation shaft, and also pulls air into the rail tunnel from the closest ventilation shaft behind it.[4][5] The diameter of both downtown tubes is 15 feet 3 inches (4.65 m).[6][5] The underwater section of the tubes is about 5,700 feet (1,737 m) in total.[1][5] The tubes were formed by segmental circular linings of cast-steel, bolted together at the rear of the excavating shields as the shields were driven forward. The tubes are lined with concrete below the top of the cable ducts, and are unlined above these ducts.[5] On the Manhattan end, the tubes were connected by a balloon loop. The loop fanned out to include five tracks served by six platforms. This layout was built during the construction of the original Hudson Terminal, and a similar layout existed in two of the successive World Trade Center PATH stations that replaced it.[7]: 59–60 The current World Trade Center PATH station includes four platforms, but the general track layout, with the five-track balloon loop, is otherwise similar to that of the previous World Trade Center stations.[8]: S.10 [9] HistoryThe tunnels were the second non-waterborne connection between Manhattan and New Jersey, after the Uptown Hudson Tubes.[7]: 15 The idea for the downtown tunnels was devised by another company in 1903, the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Corporation (H&M). However, William Gibbs McAdoo's New York and Jersey Railroad Company, which was constructing the Uptown Tubes, was interested in the H&M tunnel.[10] Early in the planning process, there were elaborate reports that the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) was interested in operating its trains through the Downtown Hudson Tubes, so that the PRR's New York Penn Station could be used solely for non-terminating trains. However, McAdoo denied these rumors, saying, "the Pennsylvania has not one dollar's interest" in such a venture.[11] In January 1905, the Hudson Companies was incorporated for the purpose of completing the Uptown Hudson Tubes. The Hudson Companies would also build a pair of downtown tunnels between the Exchange Place station, in Jersey City, and Hudson Terminal, at the corner of Church and Cortlandt Streets in Lower Manhattan. The company already had a capital of $21 million at the time of its incorporation.[12][13] Work on the underwater section of the Downtown Tubes started in April 1905.[14] That June, the New York State Board of Commissioners approved of the layout for the Downtown Tubes' Manhattan end.[15] The Hudson and Manhattan Railroad Company was incorporated in December 1906 to operate a passenger railroad system between New York and New Jersey via the Uptown and Downtown Tubes.[16][17] The Downtown Tubes, located about 1.25 miles (2.01 km) south of the uptown pair, were well under construction by that time,[7]: 19 as 3,000 feet (910 m) of these tubes had been constructed.[17] Construction of the Downtown Tubes proceeded smoothly, and digging on the first of the Downtown Tubes was completed in January 1909, without anyone being killed during the process.[18] The tubes began service on July 19, 1909, with the opening of the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad's Hudson Terminal in lower Manhattan.[7]: 18 [19][20][21] At first, service only ran to Exchange Place, for the connection to the PRR's Exchange Place station.[22][21] Service was extended from Exchange Place to Hoboken Terminal on August 2, 1909; from Exchange Place to Grove Street in 1910; and finally from Grove Street to Park Place station in 1911.[21] When the original World Trade Center was constructed in the 1960s, the Downtown Tubes remained in service as elevated tunnels until 1970, when a new PATH station was built.[23] The new PATH station opened on July 6, 1971, and the Hudson Terminal was closed at that time.[24] The downtown and uptown tubes were declared National Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks in 1978 by the American Society of Civil Engineers.[25] The last remnant of Hudson Terminal was a cast-iron tube embedded in the original World Trade Center's foundation, located near Church Street. It was located above the level of the new PATH station, as well as that of the station's replacement after the September 11 attacks. The cast-iron tube was removed in 2008 during the construction of the new World Trade Center,[26] a small section being donated to the Shore Line Trolley Museum along with one of the PATH train cars that were trapped underground when the towers collapsed.[27] On July 7, 2006, an alleged plot to detonate explosives in the PATH's Downtown Hudson Tubes (initially said to be a plot to bomb the Holland Tunnel) was uncovered by the FBI. The plot included the detonation of a bomb that could significantly destroy and flood the tunnels, endangering all the occupants and vehicles in the tunnel at the time of the explosion. The terror planners believed that Lower Manhattan could, as a result of the explosion, be flooded due to river water surging up the remaining tunnel after the blast. Officials say that this plan was unsound due to the strength of the tunnels. Since semi-trailer trucks are currently not allowed to pass through the Holland Tunnel, and it was infeasible to carry such a bomb on board a PATH train, it was very difficult to get sufficient explosives into the tunnel to accomplish the plan. If the tunnel were to explode and allow water from the Hudson River to flood it, Lower Manhattan would be spared since the area is 2–10 feet (0.61–3.05 m) above sea level. Of the eight planners based in six different countries, three were arrested.[28] The Downtown Hudson Tubes were severely damaged by Hurricane Sandy. To accommodate repairs, service on the Newark–World Trade Center line between Exchange Place and World Trade Center was suspended during almost all weekends in 2019 and 2020, except for holidays.[29] See also

References

Further reading

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||