|

Dinornis

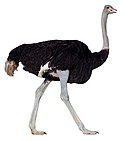

The giant moa (Dinornis) is an extinct genus of birds belonging to the moa family. As with other moa, it was a member of the order Dinornithiformes. It was endemic to New Zealand. Two species of Dinornis are considered valid, the North Island giant moa (Dinornis novaezealandiae) and the South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus). In addition, two further species (new lineage A and lineage B) have been suggested based on distinct DNA lineages.[2] Description Dinornis may have been the tallest bird that ever lived, with the females of the largest species standing 3.6 m (12 ft) tall,[3] and one of the most massive, weighing 230–240 kg (510–530 lb)[4] or 278 kg (613 lb)[5] in various estimates. Feather remains are reddish brown and hair-like, and apparently covered most of the body except the lower legs and most of the head (plus a small portion of the neck below the head). While no feathers have been found from moa chicks, it is likely that they were speckled or striped to camouflage them from Haast's Eagles.[6] The feet were large and powerful, and could probably deliver a powerful kick if threatened.[6] The birds had long, strong necks and broad sharp beaks that would have allowed them to eat vegetation from subalpine herbs through to tree branches.[6] In relation to its body, the head was small, with a pointed, short, flat and somewhat curved beak. The North Island giant moa tended to be larger than the South Island giant moa.[6] TaxonomyThe cladogram below follows a 2009 analysis by Bunce et al.:[7]

HabitatDinornis were very adaptable and were present in a wide range of habitats from coastal to alpine.[6] It is possible that individual moa would have moved from environment to environment with the changing seasons. PalaeobiologySexual dimorphism It has been long suspected that several species of moa constituted males and females, respectively. This has been confirmed by analysis for sex-specific genetic markers of DNA extracted from bone material.[8] For example, prior to 2003 there were three species of Dinornis recognised: South Island giant moa (D. robustus ), North Island giant moa (D. novaezealandiae) and slender moa (D. struthioides). However, DNA showed that all D. struthioides were in fact males, and all D. robustus were females. Therefore, the three species of Dinornis were reclassified as two species, one each formerly occurring in New Zealand's North Island (D. novaezealandiae) and South Island (D. robustus );[8][7] robustus however, comprises three distinct genetic lineages and may eventually be classified as many species. Dinornis seems to have had the most pronounced sexual dimorphism of all moa, with females being up to twice as tall and three times as heavy as males.[6] ReproductionWhile it is impossible to know exactly how Dinornis reproduced and raised young, assumptions can be made from extant ratites.[6] The larger females may have competed to mate with the most desirable males who themselves were likely to have been extremely territorial. Eggs may have been laid in communal nests in sand dunes, or by individual birds in sheltered environments such as hollow trees or by rocks. The female would have had little to do with the eggs once they had been laid while the male would have incubated the egg for up to three months before it hatched. Dinornis eggs were enormous, as large as a rugby ball, and around 80 times the volume of a chicken's egg.[6] However, despite their size, Dinornis eggs were extremely thin, with D. novaezealandiae's eggshells being around 1.06 millimeters (0.04 inches) thick and D. robustus' eggshells being 1.4 millimeters (0.06 inches) thick. As such, Dinornis eggs have been estimated to be the 'most fragile of all avian eggs measured to date'.[9] It is possible that such fragile eggs resulted in the male moa adapting to become smaller than the females to reduce the risk of crushing the eggs. However, it is possible that the male moa would curl themselves around the eggs rather than sitting on them directly.[6] Given the size of the eggs, and the incubation period, as soon as giant moa chicks hatched they would have been able to see, run and feed themselves.[6] ExtinctionPrior to the arrival of humans, the giant moa had an ecologically stable population in New Zealand for at least 40,000 years.[10] The giant moa, along with other moa genera, were wiped out by Polynesian settlers,[10] who hunted it for food. All taxa in this genus were extinct by 1500 in New Zealand. It is generally accepted that the Māori still hunted them at the beginning of the fifteenth century, although some models suggest extinction had already taken place by the middle of the 14th century.[11] Although some birds became extinct due to farming, for which the forests were cut and burned down and the ground was turned into arable land, the giant moa had been extinct for 300 years prior to the arrival of European settlers.[12] References

Amadon, D. (1947). "An estimated weight of the largest known bird". Condor. 49 (4): 159–164. doi:10.2307/1364110. JSTOR 1364110.

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Dinornis.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||