Mathematical function

The digamma function

ψ

(

z

)

{\displaystyle \psi (z)}

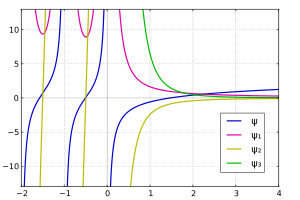

domain coloring Plots of the digamma and the next three polygamma functions along the real line (they are real-valued on the real line) In mathematics , the digamma function is defined as the logarithmic derivative of the gamma function :[ 1] [ 2] [ 3]

ψ

(

z

)

=

d

d

z

ln

Γ

(

z

)

=

Γ

′

(

z

)

Γ

(

z

)

.

{\displaystyle \psi (z)={\frac {\mathrm {d} }{\mathrm {d} z}}\ln \Gamma (z)={\frac {\Gamma '(z)}{\Gamma (z)}}.}

It is the first of the polygamma functions . This function is strictly increasing and strictly concave on

(

0

,

∞

)

{\displaystyle (0,\infty )}

[ 4] asymptotically behaves as[ 5]

ψ

(

z

)

∼

ln

z

−

1

2

z

,

{\displaystyle \psi (z)\sim \ln {z}-{\frac {1}{2z}},}

for complex numbers with large modulus (

|

z

|

→

∞

{\displaystyle |z|\rightarrow \infty }

sector

|

arg

z

|

<

π

−

ε

{\displaystyle |\arg z|<\pi -\varepsilon }

infinitesimally small positive constant

ε

{\displaystyle \varepsilon }

The digamma function is often denoted as

ψ

0

(

x

)

,

ψ

(

0

)

(

x

)

{\displaystyle \psi _{0}(x),\psi ^{(0)}(x)}

Ϝ [ 6] consonant digamma meaning double-gamma ).

Relation to harmonic numbers

The gamma function obeys the equation

Γ

(

z

+

1

)

=

z

Γ

(

z

)

.

{\displaystyle \Gamma (z+1)=z\Gamma (z).\,}

Taking the logarithm on both sides and using the functional equation property of the log-gamma function gives:

log

Γ

(

z

+

1

)

=

log

(

z

)

+

log

Γ

(

z

)

,

{\displaystyle \log \Gamma (z+1)=\log(z)+\log \Gamma (z),}

Differentiating both sides with respect to z gives:

ψ

(

z

+

1

)

=

ψ

(

z

)

+

1

z

{\displaystyle \psi (z+1)=\psi (z)+{\frac {1}{z}}}

Since the harmonic numbers are defined for positive integers n as

H

n

=

∑

k

=

1

n

1

k

,

{\displaystyle H_{n}=\sum _{k=1}^{n}{\frac {1}{k}},}

the digamma function is related to them by

ψ

(

n

)

=

H

n

−

1

−

γ

,

{\displaystyle \psi (n)=H_{n-1}-\gamma ,}

where H 0 = 0,γ is the Euler–Mascheroni constant . For half-integer arguments the digamma function takes the values

ψ

(

n

+

1

2

)

=

−

γ

−

2

ln

2

+

∑

k

=

1

n

2

2

k

−

1

=

−

γ

−

2

ln

2

+

2

H

2

n

−

H

n

.

{\displaystyle \psi \left(n+{\tfrac {1}{2}}\right)=-\gamma -2\ln 2+\sum _{k=1}^{n}{\frac {2}{2k-1}}=-\gamma -2\ln 2+2H_{2n}-H_{n}.}

Integral representations

If the real part of z is positive then the digamma function has the following integral representation due to Gauss:[ 7]

ψ

(

z

)

=

∫

0

∞

(

e

−

t

t

−

e

−

z

t

1

−

e

−

t

)

d

t

.

{\displaystyle \psi (z)=\int _{0}^{\infty }\left({\frac {e^{-t}}{t}}-{\frac {e^{-zt}}{1-e^{-t}}}\right)\,dt.}

Combining this expression with an integral identity for the Euler–Mascheroni constant

γ

{\displaystyle \gamma }

ψ

(

z

+

1

)

=

−

γ

+

∫

0

1

(

1

−

t

z

1

−

t

)

d

t

.

{\displaystyle \psi (z+1)=-\gamma +\int _{0}^{1}\left({\frac {1-t^{z}}{1-t}}\right)\,dt.}

The integral is Euler's harmonic number

H

z

{\displaystyle H_{z}}

ψ

(

z

+

1

)

=

ψ

(

1

)

+

H

z

.

{\displaystyle \psi (z+1)=\psi (1)+H_{z}.}

A consequence is the following generalization of the recurrence relation:

ψ

(

w

+

1

)

−

ψ

(

z

+

1

)

=

H

w

−

H

z

.

{\displaystyle \psi (w+1)-\psi (z+1)=H_{w}-H_{z}.}

An integral representation due to Dirichlet is:[ 7]

ψ

(

z

)

=

∫

0

∞

(

e

−

t

−

1

(

1

+

t

)

z

)

d

t

t

.

{\displaystyle \psi (z)=\int _{0}^{\infty }\left(e^{-t}-{\frac {1}{(1+t)^{z}}}\right)\,{\frac {dt}{t}}.}

Gauss's integral representation can be manipulated to give the start of the asymptotic expansion of

ψ

{\displaystyle \psi }

[ 8]

ψ

(

z

)

=

log

z

−

1

2

z

−

∫

0

∞

(

1

2

−

1

t

+

1

e

t

−

1

)

e

−

t

z

d

t

.

{\displaystyle \psi (z)=\log z-{\frac {1}{2z}}-\int _{0}^{\infty }\left({\frac {1}{2}}-{\frac {1}{t}}+{\frac {1}{e^{t}-1}}\right)e^{-tz}\,dt.}

This formula is also a consequence of Binet's first integral for the gamma function. The integral may be recognized as a Laplace transform .

Binet's second integral for the gamma function gives a different formula for

ψ

{\displaystyle \psi }

[ 9]

ψ

(

z

)

=

log

z

−

1

2

z

−

2

∫

0

∞

t

d

t

(

t

2

+

z

2

)

(

e

2

π

t

−

1

)

.

{\displaystyle \psi (z)=\log z-{\frac {1}{2z}}-2\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {t\,dt}{(t^{2}+z^{2})(e^{2\pi t}-1)}}.}

From the definition of

ψ

{\displaystyle \psi }

ψ

(

z

)

=

1

Γ

(

z

)

∫

0

∞

t

z

−

1

ln

(

t

)

e

−

t

d

t

,

{\displaystyle \psi (z)={\frac {1}{\Gamma (z)}}\int _{0}^{\infty }t^{z-1}\ln(t)e^{-t}\,dt,}

with

ℜ

z

>

0

{\displaystyle \Re z>0}

[ 10]

Infinite product representation

The function

ψ

(

z

)

/

Γ

(

z

)

{\displaystyle \psi (z)/\Gamma (z)}

[ 11]

ψ

(

z

)

Γ

(

z

)

=

−

e

2

γ

z

∏

k

=

0

∞

(

1

−

z

x

k

)

e

z

x

k

.

{\displaystyle {\frac {\psi (z)}{\Gamma (z)}}=-e^{2\gamma z}\prod _{k=0}^{\infty }\left(1-{\frac {z}{x_{k}}}\right)e^{\frac {z}{x_{k}}}.}

Here

x

k

{\displaystyle x_{k}}

k th zero of

ψ

{\displaystyle \psi }

γ

{\displaystyle \gamma }

Euler–Mascheroni constant .

Note: This is also equal to

−

d

d

z

1

Γ

(

z

)

{\displaystyle -{\frac {d}{dz}}{\frac {1}{\Gamma (z)}}}

Γ

′

(

z

)

Γ

(

z

)

=

ψ

(

z

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {\Gamma '(z)}{\Gamma (z)}}=\psi (z)}

Series representation

Euler's product formula for the gamma function, combined with the functional equation and an identity for the Euler–Mascheroni constant, yields the following expression for the digamma function, valid in the complex plane outside the negative integers (Abramowitz and Stegun 6.3.16):[ 1]

ψ

(

z

+

1

)

=

−

γ

+

∑

n

=

1

∞

(

1

n

−

1

n

+

z

)

,

z

≠

−

1

,

−

2

,

−

3

,

…

,

=

−

γ

+

∑

n

=

1

∞

(

z

n

(

n

+

z

)

)

,

z

≠

−

1

,

−

2

,

−

3

,

…

.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\psi (z+1)&=-\gamma +\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }\left({\frac {1}{n}}-{\frac {1}{n+z}}\right),\qquad z\neq -1,-2,-3,\ldots ,\\&=-\gamma +\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }\left({\frac {z}{n(n+z)}}\right),\qquad z\neq -1,-2,-3,\ldots .\end{aligned}}}

Equivalently,

ψ

(

z

)

=

−

γ

+

∑

n

=

0

∞

(

1

n

+

1

−

1

n

+

z

)

,

z

≠

0

,

−

1

,

−

2

,

…

,

=

−

γ

+

∑

n

=

0

∞

z

−

1

(

n

+

1

)

(

n

+

z

)

,

z

≠

0

,

−

1

,

−

2

,

…

.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\psi (z)&=-\gamma +\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }\left({\frac {1}{n+1}}-{\frac {1}{n+z}}\right),\qquad z\neq 0,-1,-2,\ldots ,\\&=-\gamma +\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {z-1}{(n+1)(n+z)}},\qquad z\neq 0,-1,-2,\ldots .\end{aligned}}}

Evaluation of sums of rational functions

The above identity can be used to evaluate sums of the form

∑

n

=

0

∞

u

n

=

∑

n

=

0

∞

p

(

n

)

q

(

n

)

,

{\displaystyle \sum _{n=0}^{\infty }u_{n}=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {p(n)}{q(n)}},}

where p (n )q (n )n .

Performing partial fraction on un in the complex field, in the case when all roots of q (n )

u

n

=

p

(

n

)

q

(

n

)

=

∑

k

=

1

m

a

k

n

+

b

k

.

{\displaystyle u_{n}={\frac {p(n)}{q(n)}}=\sum _{k=1}^{m}{\frac {a_{k}}{n+b_{k}}}.}

For the series to converge,

lim

n

→

∞

n

u

n

=

0

,

{\displaystyle \lim _{n\to \infty }nu_{n}=0,}

otherwise the series will be greater than the harmonic series and thus diverge. Hence

∑

k

=

1

m

a

k

=

0

,

{\displaystyle \sum _{k=1}^{m}a_{k}=0,}

and

∑

n

=

0

∞

u

n

=

∑

n

=

0

∞

∑

k

=

1

m

a

k

n

+

b

k

=

∑

n

=

0

∞

∑

k

=

1

m

a

k

(

1

n

+

b

k

−

1

n

+

1

)

=

∑

k

=

1

m

(

a

k

∑

n

=

0

∞

(

1

n

+

b

k

−

1

n

+

1

)

)

=

−

∑

k

=

1

m

a

k

(

ψ

(

b

k

)

+

γ

)

=

−

∑

k

=

1

m

a

k

ψ

(

b

k

)

.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }u_{n}&=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }\sum _{k=1}^{m}{\frac {a_{k}}{n+b_{k}}}\\&=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }\sum _{k=1}^{m}a_{k}\left({\frac {1}{n+b_{k}}}-{\frac {1}{n+1}}\right)\\&=\sum _{k=1}^{m}\left(a_{k}\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }\left({\frac {1}{n+b_{k}}}-{\frac {1}{n+1}}\right)\right)\\&=-\sum _{k=1}^{m}a_{k}{\big (}\psi (b_{k})+\gamma {\big )}\\&=-\sum _{k=1}^{m}a_{k}\psi (b_{k}).\end{aligned}}}

With the series expansion of higher rank polygamma function a generalized formula can be given as

∑

n

=

0

∞

u

n

=

∑

n

=

0

∞

∑

k

=

1

m

a

k

(

n

+

b

k

)

r

k

=

∑

k

=

1

m

(

−

1

)

r

k

(

r

k

−

1

)

!

a

k

ψ

(

r

k

−

1

)

(

b

k

)

,

{\displaystyle \sum _{n=0}^{\infty }u_{n}=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }\sum _{k=1}^{m}{\frac {a_{k}}{(n+b_{k})^{r_{k}}}}=\sum _{k=1}^{m}{\frac {(-1)^{r_{k}}}{(r_{k}-1)!}}a_{k}\psi ^{(r_{k}-1)}(b_{k}),}

provided the series on the left converges.

Taylor series

The digamma has a rational zeta series , given by the Taylor series at z = 1

ψ

(

z

+

1

)

=

−

γ

−

∑

k

=

1

∞

(

−

1

)

k

ζ

(

k

+

1

)

z

k

,

{\displaystyle \psi (z+1)=-\gamma -\sum _{k=1}^{\infty }(-1)^{k}\,\zeta (k+1)\,z^{k},}

which converges for |z . Here, ζ (n )Riemann zeta function . This series is easily derived from the corresponding Taylor's series for the Hurwitz zeta function .

Newton series

The Newton series for the digamma, sometimes referred to as Stern series , derived by Moritz Abraham Stern in 1847,[ 12] [ 13] [ 14]

ψ

(

s

)

=

−

γ

+

(

s

−

1

)

−

(

s

−

1

)

(

s

−

2

)

2

⋅

2

!

+

(

s

−

1

)

(

s

−

2

)

(

s

−

3

)

3

⋅

3

!

⋯

,

ℜ

(

s

)

>

0

,

=

−

γ

−

∑

k

=

1

∞

(

−

1

)

k

k

(

s

−

1

k

)

⋯

,

ℜ

(

s

)

>

0.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\psi (s)&=-\gamma +(s-1)-{\frac {(s-1)(s-2)}{2\cdot 2!}}+{\frac {(s-1)(s-2)(s-3)}{3\cdot 3!}}\cdots ,\quad \Re (s)>0,\\&=-\gamma -\sum _{k=1}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{k}}{k}}{\binom {s-1}{k}}\cdots ,\quad \Re (s)>0.\end{aligned}}}

where ( s k ) binomial coefficient . It may also be generalized to

ψ

(

s

+

1

)

=

−

γ

−

1

m

∑

k

=

1

m

−

1

m

−

k

s

+

k

−

1

m

∑

k

=

1

∞

(

−

1

)

k

k

{

(

s

+

m

k

+

1

)

−

(

s

k

+

1

)

}

,

ℜ

(

s

)

>

−

1

,

{\displaystyle \psi (s+1)=-\gamma -{\frac {1}{m}}\sum _{k=1}^{m-1}{\frac {m-k}{s+k}}-{\frac {1}{m}}\sum _{k=1}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{k}}{k}}\left\{{\binom {s+m}{k+1}}-{\binom {s}{k+1}}\right\},\qquad \Re (s)>-1,}

where m = 2, 3, 4, ...[ 13]

There exist various series for the digamma containing rational coefficients only for the rational arguments. In particular, the series with Gregory's coefficients G n

ψ

(

v

)

=

ln

v

−

∑

n

=

1

∞

|

G

n

|

(

n

−

1

)

!

(

v

)

n

,

ℜ

(

v

)

>

0

,

{\displaystyle \psi (v)=\ln v-\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {{\big |}G_{n}{\big |}(n-1)!}{(v)_{n}}},\qquad \Re (v)>0,}

ψ

(

v

)

=

2

ln

Γ

(

v

)

−

2

v

ln

v

+

2

v

+

2

ln

v

−

ln

2

π

−

2

∑

n

=

1

∞

|

G

n

(

2

)

|

(

v

)

n

(

n

−

1

)

!

,

ℜ

(

v

)

>

0

,

{\displaystyle \psi (v)=2\ln \Gamma (v)-2v\ln v+2v+2\ln v-\ln 2\pi -2\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {{\big |}G_{n}(2){\big |}}{(v)_{n}}}\,(n-1)!,\qquad \Re (v)>0,}

ψ

(

v

)

=

3

ln

Γ

(

v

)

−

6

ζ

′

(

−

1

,

v

)

+

3

v

2

ln

v

−

3

2

v

2

−

6

v

ln

(

v

)

+

3

v

+

3

ln

v

−

3

2

ln

2

π

+

1

2

−

3

∑

n

=

1

∞

|

G

n

(

3

)

|

(

v

)

n

(

n

−

1

)

!

,

ℜ

(

v

)

>

0

,

{\displaystyle \psi (v)=3\ln \Gamma (v)-6\zeta '(-1,v)+3v^{2}\ln {v}-{\frac {3}{2}}v^{2}-6v\ln(v)+3v+3\ln {v}-{\frac {3}{2}}\ln 2\pi +{\frac {1}{2}}-3\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {{\big |}G_{n}(3){\big |}}{(v)_{n}}}\,(n-1)!,\qquad \Re (v)>0,}

where (v )n is the rising factorial (v )n v (v +1)(v +2) ... (v +n -1) , G n k )Gregory coefficients of higher order with G n G n Γ is the gamma function and ζ is the Hurwitz zeta function .[ 15] [ 13] C n [ 15] [ 13]

ψ

(

v

)

=

ln

(

v

−

1

)

+

∑

n

=

1

∞

C

n

(

n

−

1

)

!

(

v

)

n

,

ℜ

(

v

)

>

1

,

{\displaystyle \psi (v)=\ln(v-1)+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {C_{n}(n-1)!}{(v)_{n}}},\qquad \Re (v)>1,}

A series with the Bernoulli polynomials of the second kind has the following form[ 13]

ψ

(

v

)

=

ln

(

v

+

a

)

+

∑

n

=

1

∞

(

−

1

)

n

ψ

n

(

a

)

(

n

−

1

)

!

(

v

)

n

,

ℜ

(

v

)

>

−

a

,

{\displaystyle \psi (v)=\ln(v+a)+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{n}\psi _{n}(a)\,(n-1)!}{(v)_{n}}},\qquad \Re (v)>-a,}

where ψn (a )Bernoulli polynomials of the second kind defined by the generating

equation

z

(

1

+

z

)

a

ln

(

1

+

z

)

=

∑

n

=

0

∞

z

n

ψ

n

(

a

)

,

|

z

|

<

1

,

{\displaystyle {\frac {z(1+z)^{a}}{\ln(1+z)}}=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }z^{n}\psi _{n}(a)\,,\qquad |z|<1\,,}

It may be generalized to

ψ

(

v

)

=

1

r

∑

l

=

0

r

−

1

ln

(

v

+

a

+

l

)

+

1

r

∑

n

=

1

∞

(

−

1

)

n

N

n

,

r

(

a

)

(

n

−

1

)

!

(

v

)

n

,

ℜ

(

v

)

>

−

a

,

r

=

1

,

2

,

3

,

…

{\displaystyle \psi (v)={\frac {1}{r}}\sum _{l=0}^{r-1}\ln(v+a+l)+{\frac {1}{r}}\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{n}N_{n,r}(a)(n-1)!}{(v)_{n}}},\qquad \Re (v)>-a,\quad r=1,2,3,\ldots }

where the polynomials Nn,r (a )

(

1

+

z

)

a

+

m

−

(

1

+

z

)

a

ln

(

1

+

z

)

=

∑

n

=

0

∞

N

n

,

m

(

a

)

z

n

,

|

z

|

<

1

,

{\displaystyle {\frac {(1+z)^{a+m}-(1+z)^{a}}{\ln(1+z)}}=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }N_{n,m}(a)z^{n},\qquad |z|<1,}

so that Nn,1 (a ) = ψn (a )[ 13] [ 13]

ψ

(

v

)

=

1

v

+

a

−

1

2

{

ln

Γ

(

v

+

a

)

+

v

−

1

2

ln

2

π

−

1

2

+

∑

n

=

1

∞

(

−

1

)

n

ψ

n

+

1

(

a

)

(

v

)

n

(

n

−

1

)

!

}

,

ℜ

(

v

)

>

−

a

,

{\displaystyle \psi (v)={\frac {1}{v+a-{\tfrac {1}{2}}}}\left\{\ln \Gamma (v+a)+v-{\frac {1}{2}}\ln 2\pi -{\frac {1}{2}}+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{n}\psi _{n+1}(a)}{(v)_{n}}}(n-1)!\right\},\qquad \Re (v)>-a,}

and

ψ

(

v

)

=

1

1

2

r

+

v

+

a

−

1

{

ln

Γ

(

v

+

a

)

+

v

−

1

2

ln

2

π

−

1

2

+

1

r

∑

n

=

0

r

−

2

(

r

−

n

−

1

)

ln

(

v

+

a

+

n

)

+

1

r

∑

n

=

1

∞

(

−

1

)

n

N

n

+

1

,

r

(

a

)

(

v

)

n

(

n

−

1

)

!

}

,

{\displaystyle \psi (v)={\frac {1}{{\tfrac {1}{2}}r+v+a-1}}\left\{\ln \Gamma (v+a)+v-{\frac {1}{2}}\ln 2\pi -{\frac {1}{2}}+{\frac {1}{r}}\sum _{n=0}^{r-2}(r-n-1)\ln(v+a+n)+{\frac {1}{r}}\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {(-1)^{n}N_{n+1,r}(a)}{(v)_{n}}}(n-1)!\right\},}

where

ℜ

(

v

)

>

−

a

{\displaystyle \Re (v)>-a}

r

=

2

,

3

,

4

,

…

{\displaystyle r=2,3,4,\ldots }

The digamma and polygamma functions satisfy reflection formulas similar to that of the gamma function :

ψ

(

1

−

x

)

−

ψ

(

x

)

=

π

cot

π

x

{\displaystyle \psi (1-x)-\psi (x)=\pi \cot \pi x}

ψ

′

(

−

x

)

+

ψ

′

(

x

)

=

π

2

sin

2

(

π

x

)

+

1

x

2

{\displaystyle \psi '(-x)+\psi '(x)={\frac {\pi ^{2}}{\sin ^{2}(\pi x)}}+{\frac {1}{x^{2}}}}

The digamma function satisfies the recurrence relation

ψ

(

x

+

1

)

=

ψ

(

x

)

+

1

x

.

{\displaystyle \psi (x+1)=\psi (x)+{\frac {1}{x}}.}

Thus, it can be said to "telescope" 1 / x

Δ

[

ψ

]

(

x

)

=

1

x

{\displaystyle \Delta [\psi ](x)={\frac {1}{x}}}

where Δ is the forward difference operator . This satisfies the recurrence relation of a partial sum of the harmonic series , thus implying the formula

ψ

(

n

)

=

H

n

−

1

−

γ

{\displaystyle \psi (n)=H_{n-1}-\gamma }

where γ is the Euler–Mascheroni constant .

Actually, ψ is the only solution of the functional equation

F

(

x

+

1

)

=

F

(

x

)

+

1

x

{\displaystyle F(x+1)=F(x)+{\frac {1}{x}}}

that is monotonic on R + F (1) = −γ Γ function given its recurrence equation and convexity restriction. This implies the useful difference equation:

ψ

(

x

+

N

)

−

ψ

(

x

)

=

∑

k

=

0

N

−

1

1

x

+

k

{\displaystyle \psi (x+N)-\psi (x)=\sum _{k=0}^{N-1}{\frac {1}{x+k}}}

Some finite sums involving the digamma function

There are numerous finite summation formulas for the digamma function. Basic summation formulas, such as

∑

r

=

1

m

ψ

(

r

m

)

=

−

m

(

γ

+

ln

m

)

,

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=1}^{m}\psi \left({\frac {r}{m}}\right)=-m(\gamma +\ln m),}

∑

r

=

1

m

ψ

(

r

m

)

⋅

exp

2

π

r

k

i

m

=

m

ln

(

1

−

exp

2

π

k

i

m

)

,

k

∈

Z

,

m

∈

N

,

k

≠

m

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=1}^{m}\psi \left({\frac {r}{m}}\right)\cdot \exp {\dfrac {2\pi rki}{m}}=m\ln \left(1-\exp {\frac {2\pi ki}{m}}\right),\qquad k\in \mathbb {Z} ,\quad m\in \mathbb {N} ,\ k\neq m}

∑

r

=

1

m

−

1

ψ

(

r

m

)

⋅

cos

2

π

r

k

m

=

m

ln

(

2

sin

k

π

m

)

+

γ

,

k

=

1

,

2

,

…

,

m

−

1

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=1}^{m-1}\psi \left({\frac {r}{m}}\right)\cdot \cos {\dfrac {2\pi rk}{m}}=m\ln \left(2\sin {\frac {k\pi }{m}}\right)+\gamma ,\qquad k=1,2,\ldots ,m-1}

∑

r

=

1

m

−

1

ψ

(

r

m

)

⋅

sin

2

π

r

k

m

=

π

2

(

2

k

−

m

)

,

k

=

1

,

2

,

…

,

m

−

1

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=1}^{m-1}\psi \left({\frac {r}{m}}\right)\cdot \sin {\frac {2\pi rk}{m}}={\frac {\pi }{2}}(2k-m),\qquad k=1,2,\ldots ,m-1}

are due to Gauss.[ 16] [ 17]

∑

r

=

0

m

−

1

ψ

(

2

r

+

1

2

m

)

⋅

cos

(

2

r

+

1

)

k

π

m

=

m

ln

(

tan

π

k

2

m

)

,

k

=

1

,

2

,

…

,

m

−

1

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=0}^{m-1}\psi \left({\frac {2r+1}{2m}}\right)\cdot \cos {\frac {(2r+1)k\pi }{m}}=m\ln \left(\tan {\frac {\pi k}{2m}}\right),\qquad k=1,2,\ldots ,m-1}

∑

r

=

0

m

−

1

ψ

(

2

r

+

1

2

m

)

⋅

sin

(

2

r

+

1

)

k

π

m

=

−

π

m

2

,

k

=

1

,

2

,

…

,

m

−

1

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=0}^{m-1}\psi \left({\frac {2r+1}{2m}}\right)\cdot \sin {\dfrac {(2r+1)k\pi }{m}}=-{\frac {\pi m}{2}},\qquad k=1,2,\ldots ,m-1}

∑

r

=

1

m

−

1

ψ

(

r

m

)

⋅

cot

π

r

m

=

−

π

(

m

−

1

)

(

m

−

2

)

6

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=1}^{m-1}\psi \left({\frac {r}{m}}\right)\cdot \cot {\frac {\pi r}{m}}=-{\frac {\pi (m-1)(m-2)}{6}}}

∑

r

=

1

m

−

1

ψ

(

r

m

)

⋅

r

m

=

−

γ

2

(

m

−

1

)

−

m

2

ln

m

−

π

2

∑

r

=

1

m

−

1

r

m

⋅

cot

π

r

m

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=1}^{m-1}\psi \left({\frac {r}{m}}\right)\cdot {\frac {r}{m}}=-{\frac {\gamma }{2}}(m-1)-{\frac {m}{2}}\ln m-{\frac {\pi }{2}}\sum _{r=1}^{m-1}{\frac {r}{m}}\cdot \cot {\frac {\pi r}{m}}}

∑

r

=

1

m

−

1

ψ

(

r

m

)

⋅

cos

(

2

ℓ

+

1

)

π

r

m

=

−

π

m

∑

r

=

1

m

−

1

r

⋅

sin

2

π

r

m

cos

2

π

r

m

−

cos

(

2

ℓ

+

1

)

π

m

,

ℓ

∈

Z

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=1}^{m-1}\psi \left({\frac {r}{m}}\right)\cdot \cos {\dfrac {(2\ell +1)\pi r}{m}}=-{\frac {\pi }{m}}\sum _{r=1}^{m-1}{\frac {r\cdot \sin {\dfrac {2\pi r}{m}}}{\cos {\dfrac {2\pi r}{m}}-\cos {\dfrac {(2\ell +1)\pi }{m}}}},\qquad \ell \in \mathbb {Z} }

∑

r

=

1

m

−

1

ψ

(

r

m

)

⋅

sin

(

2

ℓ

+

1

)

π

r

m

=

−

(

γ

+

ln

2

m

)

cot

(

2

ℓ

+

1

)

π

2

m

+

sin

(

2

ℓ

+

1

)

π

m

∑

r

=

1

m

−

1

ln

sin

π

r

m

cos

2

π

r

m

−

cos

(

2

ℓ

+

1

)

π

m

,

ℓ

∈

Z

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=1}^{m-1}\psi \left({\frac {r}{m}}\right)\cdot \sin {\dfrac {(2\ell +1)\pi r}{m}}=-(\gamma +\ln 2m)\cot {\frac {(2\ell +1)\pi }{2m}}+\sin {\dfrac {(2\ell +1)\pi }{m}}\sum _{r=1}^{m-1}{\frac {\ln \sin {\dfrac {\pi r}{m}}}{\cos {\dfrac {2\pi r}{m}}-\cos {\dfrac {(2\ell +1)\pi }{m}}}},\qquad \ell \in \mathbb {Z} }

∑

r

=

1

m

−

1

ψ

2

(

r

m

)

=

(

m

−

1

)

γ

2

+

m

(

2

γ

+

ln

4

m

)

ln

m

−

m

(

m

−

1

)

ln

2

2

+

π

2

(

m

2

−

3

m

+

2

)

12

+

m

∑

ℓ

=

1

m

−

1

ln

2

sin

π

ℓ

m

{\displaystyle \sum _{r=1}^{m-1}\psi ^{2}\left({\frac {r}{m}}\right)=(m-1)\gamma ^{2}+m(2\gamma +\ln 4m)\ln {m}-m(m-1)\ln ^{2}2+{\frac {\pi ^{2}(m^{2}-3m+2)}{12}}+m\sum _{\ell =1}^{m-1}\ln ^{2}\sin {\frac {\pi \ell }{m}}}

are due to works of certain modern authors (see e.g. Appendix B in Blagouchine (2014)[ 18]

We also have [ 19]

1

+

1

2

+

1

3

+

.

.

.

+

1

k

−

1

−

γ

=

1

k

∑

n

=

0

k

−

1

ψ

(

1

+

n

k

)

,

k

=

2

,

3

,

.

.

.

{\displaystyle 1+{\frac {1}{2}}+{\frac {1}{3}}+...+{\frac {1}{k-1}}-\gamma ={\frac {1}{k}}\sum _{n=0}^{k-1}\psi \left(1+{\frac {n}{k}}\right),k=2,3,...}

For positive integers r and m (r < m Euler's constant and a finite number of elementary functions [ 20]

ψ

(

r

m

)

=

−

γ

−

ln

(

2

m

)

−

π

2

cot

(

r

π

m

)

+

2

∑

n

=

1

⌊

m

−

1

2

⌋

cos

(

2

π

n

r

m

)

ln

sin

(

π

n

m

)

{\displaystyle \psi \left({\frac {r}{m}}\right)=-\gamma -\ln(2m)-{\frac {\pi }{2}}\cot \left({\frac {r\pi }{m}}\right)+2\sum _{n=1}^{\left\lfloor {\frac {m-1}{2}}\right\rfloor }\cos \left({\frac {2\pi nr}{m}}\right)\ln \sin \left({\frac {\pi n}{m}}\right)}

which holds, because of its recurrence equation, for all rational arguments.

Multiplication theorem

The multiplication theorem of the

Γ

{\displaystyle \Gamma }

[ 21]

ψ

(

n

z

)

=

1

n

∑

k

=

0

n

−

1

ψ

(

z

+

k

n

)

+

ln

n

.

{\displaystyle \psi (nz)={\frac {1}{n}}\sum _{k=0}^{n-1}\psi \left(z+{\frac {k}{n}}\right)+\ln n.}

Asymptotic expansion

The digamma function has the asymptotic expansion

ψ

(

z

)

∼

ln

z

+

∑

n

=

1

∞

ζ

(

1

−

n

)

z

n

=

ln

z

−

∑

n

=

1

∞

B

n

n

z

n

,

{\displaystyle \psi (z)\sim \ln z+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {\zeta (1-n)}{z^{n}}}=\ln z-\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }{\frac {B_{n}}{nz^{n}}},}

where B k k Bernoulli number and ζ is the Riemann zeta function . The first few terms of this expansion are:

ψ

(

z

)

∼

ln

z

−

1

2

z

−

1

12

z

2

+

1

120

z

4

−

1

252

z

6

+

1

240

z

8

−

1

132

z

10

+

691

32760

z

12

−

1

12

z

14

+

⋯

.

{\displaystyle \psi (z)\sim \ln z-{\frac {1}{2z}}-{\frac {1}{12z^{2}}}+{\frac {1}{120z^{4}}}-{\frac {1}{252z^{6}}}+{\frac {1}{240z^{8}}}-{\frac {1}{132z^{10}}}+{\frac {691}{32760z^{12}}}-{\frac {1}{12z^{14}}}+\cdots .}

Although the infinite sum does not converge for any z z

The expansion can be found by applying the Euler–Maclaurin formula to the sum[ 22]

∑

n

=

1

∞

(

1

n

−

1

z

+

n

)

{\displaystyle \sum _{n=1}^{\infty }\left({\frac {1}{n}}-{\frac {1}{z+n}}\right)}

The expansion can also be derived from the integral representation coming from Binet's second integral formula for the gamma function. Expanding

t

/

(

t

2

+

z

2

)

{\displaystyle t/(t^{2}+z^{2})}

geometric series and substituting an integral representation of the Bernoulli numbers leads to the same asymptotic series as above. Furthermore, expanding only finitely many terms of the series gives a formula with an explicit error term:

ψ

(

z

)

=

ln

z

−

1

2

z

−

∑

n

=

1

N

B

2

n

2

n

z

2

n

+

(

−

1

)

N

+

1

2

z

2

N

∫

0

∞

t

2

N

+

1

d

t

(

t

2

+

z

2

)

(

e

2

π

t

−

1

)

.

{\displaystyle \psi (z)=\ln z-{\frac {1}{2z}}-\sum _{n=1}^{N}{\frac {B_{2n}}{2nz^{2n}}}+(-1)^{N+1}{\frac {2}{z^{2N}}}\int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {t^{2N+1}\,dt}{(t^{2}+z^{2})(e^{2\pi t}-1)}}.}

Inequalities

When x > 0

ln

x

−

1

2

x

−

ψ

(

x

)

{\displaystyle \ln x-{\frac {1}{2x}}-\psi (x)}

is completely monotonic and in particular positive. This is a consequence of Bernstein's theorem on monotone functions applied to the integral representation coming from Binet's first integral for the gamma function. Additionally, by the convexity inequality

1

+

t

≤

e

t

{\displaystyle 1+t\leq e^{t}}

e

−

t

z

/

2

{\displaystyle e^{-tz}/2}

1

x

−

ln

x

+

ψ

(

x

)

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{x}}-\ln x+\psi (x)}

is also completely monotonic. It follows that, for all x > 0

ln

x

−

1

x

≤

ψ

(

x

)

≤

ln

x

−

1

2

x

.

{\displaystyle \ln x-{\frac {1}{x}}\leq \psi (x)\leq \ln x-{\frac {1}{2x}}.}

This recovers a theorem of Horst Alzer.[ 23] s ∈ (0, 1)

1

−

s

x

+

s

<

ψ

(

x

+

1

)

−

ψ

(

x

+

s

)

,

{\displaystyle {\frac {1-s}{x+s}}<\psi (x+1)-\psi (x+s),}

Related bounds were obtained by Elezovic, Giordano, and Pecaric, who proved that, for x > 0

ln

(

x

+

1

2

)

−

1

x

<

ψ

(

x

)

<

ln

(

x

+

e

−

γ

)

−

1

x

,

{\displaystyle \ln(x+{\tfrac {1}{2}})-{\frac {1}{x}}<\psi (x)<\ln(x+e^{-\gamma })-{\frac {1}{x}},}

where

γ

=

−

ψ

(

1

)

{\displaystyle \gamma =-\psi (1)}

Euler–Mascheroni constant .[ 24]

0.5

{\displaystyle 0.5}

e

−

γ

≈

0.56

{\displaystyle e^{-\gamma }\approx 0.56}

[ 25]

The mean value theorem implies the following analog of Gautschi's inequality : If x > c c ≈ 1.461s > 0

exp

(

(

1

−

s

)

ψ

′

(

x

+

1

)

ψ

(

x

+

1

)

)

≤

ψ

(

x

+

1

)

ψ

(

x

+

s

)

≤

exp

(

(

1

−

s

)

ψ

′

(

x

+

s

)

ψ

(

x

+

s

)

)

.

{\displaystyle \exp \left((1-s){\frac {\psi '(x+1)}{\psi (x+1)}}\right)\leq {\frac {\psi (x+1)}{\psi (x+s)}}\leq \exp \left((1-s){\frac {\psi '(x+s)}{\psi (x+s)}}\right).}

Moreover, equality holds if and only if s = 1[ 26]

Inspired by the harmonic mean value inequality for the classical gamma function, Horzt Alzer and Graham Jameson proved, among other things, a harmonic mean-value inequality for the digamma function:

−

γ

≤

2

ψ

(

x

)

ψ

(

1

x

)

ψ

(

x

)

+

ψ

(

1

x

)

{\displaystyle -\gamma \leq {\frac {2\psi (x)\psi ({\frac {1}{x}})}{\psi (x)+\psi ({\frac {1}{x}})}}}

x

>

0

{\displaystyle x>0}

Equality holds if and only if

x

=

1

{\displaystyle x=1}

[ 27]

Computation and approximation

The asymptotic expansion gives an easy way to compute ψ (x )x ψ (x )x , the recurrence relation

ψ

(

x

+

1

)

=

1

x

+

ψ

(

x

)

{\displaystyle \psi (x+1)={\frac {1}{x}}+\psi (x)}

can be used to shift the value of x to a higher value. Beal[ 28] x to a value greater than 6 and then applying the above expansion with terms above x 14

As x goes to infinity, ψ (x )ln(x − 1 / 2 ) and ln x . Going down from x + 1x , ψ decreases by 1 / x ln(x − 1 / 2 ) decreases by ln(x + 1 / 2 ) / (x − 1 / 2 ) , which is more than 1 / x ln x decreases by ln(1 + 1 / x ) , which is less than 1 / x x greater than 1 / 2

ψ

(

x

)

∈

(

ln

(

x

−

1

2

)

,

ln

x

)

{\displaystyle \psi (x)\in \left(\ln \left(x-{\tfrac {1}{2}}\right),\ln x\right)}

or, for any positive x ,

exp

ψ

(

x

)

∈

(

x

−

1

2

,

x

)

.

{\displaystyle \exp \psi (x)\in \left(x-{\tfrac {1}{2}},x\right).}

The exponential exp ψ (x ) is approximately x − 1 / 2 x , but gets closer to x at small x , approaching 0 at x = 0

For x < 1ψ (x ) ∈ [−γ , 1 − γ ]

ψ

(

x

)

∈

(

−

1

x

−

γ

,

1

−

1

x

−

γ

)

,

x

∈

(

0

,

1

)

{\displaystyle \psi (x)\in \left(-{\frac {1}{x}}-\gamma ,1-{\frac {1}{x}}-\gamma \right),\quad x\in (0,1)}

or

exp

ψ

(

x

)

∈

(

exp

(

−

1

x

−

γ

)

,

e

exp

(

−

1

x

−

γ

)

)

.

{\displaystyle \exp \psi (x)\in \left(\exp \left(-{\frac {1}{x}}-\gamma \right),e\exp \left(-{\frac {1}{x}}-\gamma \right)\right).}

From the above asymptotic series for ψ , one can derive an asymptotic series for exp(−ψ (x )) . The series matches the overall behaviour well, that is, it behaves asymptotically as it should for large arguments, and has a zero of unbounded multiplicity at the origin too.

1

exp

ψ

(

x

)

∼

1

x

+

1

2

⋅

x

2

+

5

4

⋅

3

!

⋅

x

3

+

3

2

⋅

4

!

⋅

x

4

+

47

48

⋅

5

!

⋅

x

5

−

5

16

⋅

6

!

⋅

x

6

+

⋯

{\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\exp \psi (x)}}\sim {\frac {1}{x}}+{\frac {1}{2\cdot x^{2}}}+{\frac {5}{4\cdot 3!\cdot x^{3}}}+{\frac {3}{2\cdot 4!\cdot x^{4}}}+{\frac {47}{48\cdot 5!\cdot x^{5}}}-{\frac {5}{16\cdot 6!\cdot x^{6}}}+\cdots }

This is similar to a Taylor expansion of exp(−ψ (1 / y )) at y = 0[ 29] analytic at infinity.) A similar series exists for exp(ψ (x )) which starts with

exp

ψ

(

x

)

∼

x

−

1

2

.

{\displaystyle \exp \psi (x)\sim x-{\frac {1}{2}}.}

If one calculates the asymptotic series for ψ (x +1/2)x (there is no x −1 term). This leads to the following asymptotic expansion, which saves computing terms of even order.

exp

ψ

(

x

+

1

2

)

∼

x

+

1

4

!

⋅

x

−

37

8

⋅

6

!

⋅

x

3

+

10313

72

⋅

8

!

⋅

x

5

−

5509121

384

⋅

10

!

⋅

x

7

+

⋯

{\displaystyle \exp \psi \left(x+{\tfrac {1}{2}}\right)\sim x+{\frac {1}{4!\cdot x}}-{\frac {37}{8\cdot 6!\cdot x^{3}}}+{\frac {10313}{72\cdot 8!\cdot x^{5}}}-{\frac {5509121}{384\cdot 10!\cdot x^{7}}}+\cdots }

Similar in spirit to the Lanczos approximation of the

Γ

{\displaystyle \Gamma }

Spouge's approximation .

Another alternative is to use the recurrence relation or the multiplication formula to shift the argument of

ψ

(

x

)

{\displaystyle \psi (x)}

1

≤

x

≤

3

{\displaystyle 1\leq x\leq 3}

[ 30] [ 31]

Special values

The digamma function has values in closed form for rational numbers, as a result of Gauss's digamma theorem . Some are listed below:

ψ

(

1

)

=

−

γ

ψ

(

1

2

)

=

−

2

ln

2

−

γ

ψ

(

1

3

)

=

−

π

2

3

−

3

ln

3

2

−

γ

ψ

(

1

4

)

=

−

π

2

−

3

ln

2

−

γ

ψ

(

1

6

)

=

−

π

3

2

−

2

ln

2

−

3

ln

3

2

−

γ

ψ

(

1

8

)

=

−

π

2

−

4

ln

2

−

π

+

ln

(

2

+

1

)

−

ln

(

2

−

1

)

2

−

γ

.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\psi (1)&=-\gamma \\\psi \left({\tfrac {1}{2}}\right)&=-2\ln {2}-\gamma \\\psi \left({\tfrac {1}{3}}\right)&=-{\frac {\pi }{2{\sqrt {3}}}}-{\frac {3\ln {3}}{2}}-\gamma \\\psi \left({\tfrac {1}{4}}\right)&=-{\frac {\pi }{2}}-3\ln {2}-\gamma \\\psi \left({\tfrac {1}{6}}\right)&=-{\frac {\pi {\sqrt {3}}}{2}}-2\ln {2}-{\frac {3\ln {3}}{2}}-\gamma \\\psi \left({\tfrac {1}{8}}\right)&=-{\frac {\pi }{2}}-4\ln {2}-{\frac {\pi +\ln \left({\sqrt {2}}+1\right)-\ln \left({\sqrt {2}}-1\right)}{\sqrt {2}}}-\gamma .\end{aligned}}}

Moreover, by taking the logarithmic derivative of

|

Γ

(

b

i

)

|

2

{\displaystyle |\Gamma (bi)|^{2}}

|

Γ

(

1

2

+

b

i

)

|

2

{\displaystyle |\Gamma ({\tfrac {1}{2}}+bi)|^{2}}

b

{\displaystyle b}

Im

ψ

(

b

i

)

=

1

2

b

+

π

2

coth

(

π

b

)

,

{\displaystyle \operatorname {Im} \psi (bi)={\frac {1}{2b}}+{\frac {\pi }{2}}\coth(\pi b),}

Im

ψ

(

1

2

+

b

i

)

=

π

2

tanh

(

π

b

)

.

{\displaystyle \operatorname {Im} \psi ({\tfrac {1}{2}}+bi)={\frac {\pi }{2}}\tanh(\pi b).}

Apart from Gauss's digamma theorem, no such closed formula is known for the real part in general. We have, for example, at the imaginary unit the numerical approximation

Re

ψ

(

i

)

=

−

γ

−

∑

n

=

0

∞

n

−

1

n

3

+

n

2

+

n

+

1

≈

0.09465.

{\displaystyle \operatorname {Re} \psi (i)=-\gamma -\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {n-1}{n^{3}+n^{2}+n+1}}\approx 0.09465.}

Roots of the digamma function

The roots of the digamma function are the saddle points of the complex-valued gamma function. Thus they lie all on the real axis . The only one on the positive real axis is the unique minimum of the real-valued gamma function on R + x 0 = 632 144 968 362 341 26

x 1 = 083 008 264 455 409 25 x 2 = 498 473 162 390 458 77 x 3 = 720 868 444 144 650 00 x 4 = 293 366 436 901 097 83

⋮

{\displaystyle \vdots }

Already in 1881, Charles Hermite observed[ 32]

x

n

=

−

n

+

1

ln

n

+

O

(

1

(

ln

n

)

2

)

{\displaystyle x_{n}=-n+{\frac {1}{\ln n}}+O\left({\frac {1}{(\ln n)^{2}}}\right)}

holds asymptotically. A better approximation of the location of the roots is given by

x

n

≈

−

n

+

1

π

arctan

(

π

ln

n

)

n

≥

2

{\displaystyle x_{n}\approx -n+{\frac {1}{\pi }}\arctan \left({\frac {\pi }{\ln n}}\right)\qquad n\geq 2}

and using a further term it becomes still better

x

n

≈

−

n

+

1

π

arctan

(

π

ln

n

+

1

8

n

)

n

≥

1

{\displaystyle x_{n}\approx -n+{\frac {1}{\pi }}\arctan \left({\frac {\pi }{\ln n+{\frac {1}{8n}}}}\right)\qquad n\geq 1}

which both spring off the reflection formula via

0

=

ψ

(

1

−

x

n

)

=

ψ

(

x

n

)

+

π

tan

π

x

n

{\displaystyle 0=\psi (1-x_{n})=\psi (x_{n})+{\frac {\pi }{\tan \pi x_{n}}}}

and substituting ψ (xn )1 / 2n n .

Another improvement of Hermite's formula can be given:[ 11]

x

n

=

−

n

+

1

log

n

−

1

2

n

(

log

n

)

2

+

O

(

1

n

2

(

log

n

)

2

)

.

{\displaystyle x_{n}=-n+{\frac {1}{\log n}}-{\frac {1}{2n(\log n)^{2}}}+O\left({\frac {1}{n^{2}(\log n)^{2}}}\right).}

Regarding the zeros, the following infinite sum identities were recently proved by István Mező and Michael Hoffman[ 11] [ 33]

∑

n

=

0

∞

1

x

n

2

=

γ

2

+

π

2

2

,

∑

n

=

0

∞

1

x

n

3

=

−

4

ζ

(

3

)

−

γ

3

−

γ

π

2

2

,

∑

n

=

0

∞

1

x

n

4

=

γ

4

+

π

4

9

+

2

3

γ

2

π

2

+

4

γ

ζ

(

3

)

.

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{x_{n}^{2}}}&=\gamma ^{2}+{\frac {\pi ^{2}}{2}},\\\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{x_{n}^{3}}}&=-4\zeta (3)-\gamma ^{3}-{\frac {\gamma \pi ^{2}}{2}},\\\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{x_{n}^{4}}}&=\gamma ^{4}+{\frac {\pi ^{4}}{9}}+{\frac {2}{3}}\gamma ^{2}\pi ^{2}+4\gamma \zeta (3).\end{aligned}}}

In general, the function

Z

(

k

)

=

∑

n

=

0

∞

1

x

n

k

{\displaystyle Z(k)=\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{x_{n}^{k}}}}

can be determined and it is studied in detail by the cited authors.

The following results[ 11]

∑

n

=

0

∞

1

x

n

2

+

x

n

=

−

2

,

∑

n

=

0

∞

1

x

n

2

−

x

n

=

γ

+

π

2

6

γ

{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{x_{n}^{2}+x_{n}}}&=-2,\\\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{x_{n}^{2}-x_{n}}}&=\gamma +{\frac {\pi ^{2}}{6\gamma }}\end{aligned}}}

also hold true.

Regularization

The digamma function appears in the regularization of divergent integrals

∫

0

∞

d

x

x

+

a

,

{\displaystyle \int _{0}^{\infty }{\frac {dx}{x+a}},}

this integral can be approximated by a divergent general Harmonic series, but the following value can be attached to the series

∑

n

=

0

∞

1

n

+

a

=

−

ψ

(

a

)

.

{\displaystyle \sum _{n=0}^{\infty }{\frac {1}{n+a}}=-\psi (a).}

See also

References

^ a b

Abramowitz, M.; Stegun, I. A., eds. (1972). "6.3 psi (Digamma) Function." . Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables (10th ed.). New York: Dover. pp. 258– 259.

^ "NIST. Digital Library of Mathematical Functions (DLMF), Chapter 5" .^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Digamma function" . MathWorld ^ Alzer, Horst; Jameson, Graham (2017). "A harmonic mean inequality for the digamma function and related results" (PDF) . Rendiconti del Seminario Matematico della Università di Padova . 137 : 203– 209. doi :10.4171/RSMUP/137-10 . ^ "NIST. Digital Library of Mathematical Functions (DLMF), 5.11" .^ Pairman, Eleanor (1919). Tables of the Digamma and Trigamma Functions ^ a b Whittaker and Watson, 12.3.

^ Whittaker and Watson, 12.31.

^ Whittaker and Watson, 12.32, example.

^ "NIST. Digital Library of Mathematical Functions (DLMF), 5.9" .^ a b c d Mező, István; Hoffman, Michael E. (2017). "Zeros of the digamma function and its Barnes G -function analogue". Integral Transforms and Special Functions . 28 (11): 846– 858. doi :10.1080/10652469.2017.1376193 . S2CID 126115156 . ^ Nörlund, N. E. (1924). Vorlesungen über Differenzenrechnung . Berlin: Springer.^ a b c d e f g Blagouchine, Ia. V. (2018). "Three Notes on Ser's and Hasse's Representations for the Zeta-functions" (PDF) . INTEGERS: The Electronic Journal of Combinatorial Number Theory . 18A : 1– 45. arXiv :1606.02044 Bibcode :2016arXiv160602044B . ^ "Leonhard Euler's Integral: An Historical Profile of the Gamma Function" (PDF) . Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-09-12. Retrieved 11 April 2022 .^ a b Blagouchine, Ia. V. (2016). "Two series expansions for the logarithm of the gamma function involving Stirling numbers and containing only rational coefficients for certain arguments related to π−1 ". Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications . 442 : 404– 434. arXiv :1408.3902 Bibcode :2014arXiv1408.3902B . doi :10.1016/J.JMAA.2016.04.032 . S2CID 119661147 . ^ R. Campbell. Les intégrales eulériennes et leurs applications , Dunod, Paris, 1966.

^ H.M. Srivastava and J. Choi. Series Associated with the Zeta and Related Functions , Kluwer Academic Publishers, the Netherlands, 2001.

^ Blagouchine, Iaroslav V. (2014). "A theorem for the closed-form evaluation of the first generalized Stieltjes constant at rational arguments and some related summations". Journal of Number Theory . 148 : 537– 592. arXiv :1401.3724 doi :10.1016/j.jnt.2014.08.009 . ^ Classical topi s in complex function theorey . p. 46.^ Choi, Junesang; Cvijovic, Djurdje (2007). "Values of the polygamma functions at rational arguments". Journal of Physics A . 40 (50): 15019. Bibcode :2007JPhA...4015019C . doi :10.1088/1751-8113/40/50/007 . S2CID 118527596 . ^ Gradshteyn, I. S.; Ryzhik, I. M. (2015). "8.365.5". Table of integrals, series and products . Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-12-384933-5 LCCN 2014010276 . ^ Bernardo, José M. (1976). "Algorithm AS 103 psi(digamma function) computation" (PDF) . Applied Statistics . 25 : 315– 317. doi :10.2307/2347257 . JSTOR 2347257 . ^ Alzer, Horst (1997). "On Some Inequalities for the Gamma and Psi Functions" (PDF) . Mathematics of Computation . 66 (217): 373– 389. doi :10.1090/S0025-5718-97-00807-7 . JSTOR 2153660 . ^ Elezović, Neven; Giordano, Carla; Pečarić, Josip (2000). "The best bounds in Gautschi's inequality" . Mathematical Inequalities & Applications (2): 239– 252. doi :10.7153/MIA-03-26 ^ Guo, Bai-Ni; Qi, Feng (2014). "Sharp inequalities for the psi function and harmonic numbers". Analysis . 34 (2). arXiv :0902.2524 doi :10.1515/anly-2014-0001 . S2CID 16909853 . ^ Laforgia, Andrea; Natalini, Pierpaolo (2013). "Exponential, gamma and polygamma functions: Simple proofs of classical and new inequalities" . Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications . 407 (2): 495– 504. doi :10.1016/j.jmaa.2013.05.045 ^ Alzer, Horst; Jameson, Graham (2017). "A harmonic mean inequality for the digamma function and related results" (PDF) . Rendiconti del Seminario Matematico della Università di Padova 70 (201): 203– 209. doi :10.4171/RSMUP/137-10 . ISSN 0041-8994 . LCCN 50046633 . OCLC 01761704 . S2CID 41966777 . ^ Beal, Matthew J. (2003). Variational Algorithms for Approximate Bayesian Inference (PDF) (PhD thesis). The Gatsby Computational Neuroscience Unit, University College London. pp. 265– 266. ^ If it converged to a function f (y )ln(f (y ) / y ) would have the same Maclaurin series as ln(1 / y ) − φ (1 / y ) . But this does not converge because the series given earlier for φ (x )

^ Wimp, Jet (1961). "Polynomial approximations to integral transforms". Math. Comp . 15 (74): 174– 178. doi :10.1090/S0025-5718-61-99221-3 . JSTOR 2004225 . ^ Mathar, R. J. (2004). "Chebyshev series expansion of inverse polynomials". Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics . 196 (2): 596– 607. arXiv :math/0403344 doi :10.1016/j.cam.2005.10.013 . ^ Hermite, Charles (1881). "Sur l'intégrale Eulérienne de seconde espéce". Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (90): 332– 338. doi :10.1515/crll.1881.90.332 . S2CID 118866486 . ^

Mező, István (2014). "A note on the zeros and local extrema of Digamma related functions". arXiv :1409.2971 math.CV ].

External links

OEIS : A047787 OEIS : A200064 OEIS : A020777 OEIS : A200134 OEIS : A200135 OEIS : A200138

={\frac {1}{x}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2f937d04ca5581f9bf986c18bf170bdc9b376cc8)