|

Demand Note

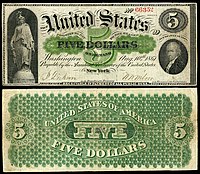

Bottom row: Prominent design elements used on the front of $5 and $20 Demand Notes (located respectively under their denomination); pictured in the middle is the front of a $10 Demand Note with prominent design elements listed A Demand Note is a type of United States paper money that was issued from August 1861 to April 1862 during the American Civil War in denominations of 5, 10, and 20 US$. Demand Notes were the first issue of paper money by the United States that achieved wide circulation. The U.S. government placed Demand Notes into circulation by using them to pay expenses incurred during the Civil War including the salaries of its workers and military personnel. Because of the distinctive green ink on their reverse, and because state-chartered bank and Confederate notes of the day typically had blank reverses, the Demand Notes were nicknamed "greenbacks", a name later inherited by United States Notes and Federal Reserve Notes. The obverse of the Demand Notes contained familiar elements such as the images of a bald eagle, Abraham Lincoln, and Alexander Hamilton, though the portraits used on Demand Notes are different from the ones seen on U.S. currency today. When Demand Notes were discontinued, their successors, the United States Notes, could not be used to pay import duties, a large part of the U.S. federal tax base at the time, and thus Demand Notes took precedence. As a result, most Demand Notes were redeemed, though the few remaining Demand Notes are the oldest valid currency in the United States today. Treasury Notes and early United States paper moneyBetween the adoption of the United States Constitution and the Civil War, the United States government did not issue paper money as it is known today. During wars and recessions it issued short term debt called Treasury Notes, but these were not legal tender. The Demand Notes were a transitional issue connecting these Treasury Notes to modern paper money. They were intended to function as money but were authorized under Congress's borrowing power because the government's authority to issue currency notes was uncertain. The Continental Congress had issued Continental dollars between 1775 and 1779 to help finance the American Revolution. The paper Continental dollars nominally entitled the bearer to an equivalent amount of Spanish milled dollars but were never redeemed in silver and lost 99% of their value by 1790 despite the American victory.[1] With the fate of the Continentals in mind, the Founding Fathers embedded in the constitution no provision for a paper currency, and the constitution explicitly prohibits states from making anything but gold or silver legal tender. As a result, the pre-Civil War circulation of banknotes in the United States consisted of private issues,[2] including issues by private federally chartered banks such as the First and the Second Bank of the United States. While the constitution did not explicitly grant the power to issue paper currency, it did grant the power to borrow money. Treasury Notes, as a form of debt, were an innovation to help bridge federal financing gaps when the government encountered difficulty selling a sufficient amount of long term bonds, or loan "stock". Treasury Notes were first employed during the War of 1812 and were issued irregularly up through the Civil War. Characteristically the issues were not extensive and the "polite fiction" was always maintained that Treasury Notes did not serve as money when, in fact, to a limited extent they did.[3] These notes usually bore interest, their value varied with market conditions, and they rapidly disappeared from the financial system after the crisis associated with their issuance had ended. Among the several issues of Treasury Notes, of special note are the "Small Treasury Notes" of 1815 which, like the Demand Notes, did not bear interest and were intended to circulate as currency – and thus are also candidates for "the first U.S. paper money". However, only $3,392,994 were issued, and these were rapidly exchanged for bonds.[4] An indication of the limited circulation achieved by these notes is that only two issued uncancelled examples of the Small Treasury Notes are known today,[5] vs. almost 1000 examples of the Demand Notes. Pre-issuanceFederal finances had not yet recovered from the Panic of 1857 when the election of President Lincoln in 1860 made it even more difficult for the federal government to raise money in the bond market due to the increased threat of Southern secession and a possible war. At the outbreak of the Civil War the Union was depending upon hand-to-mouth borrowing to meet expenses and with the beginning of hostilities at Fort Sumter in April 1861 the burden of funding the war effort and paying employees, including soldiers in the field, offered no small challenge. One response from Congress was the Act of July 17, 1861, which allowed for $250,000,000 to be borrowed on the credit of the United States. Of this sum, up to $50,000,000 was authorized as non-interest bearing Treasury Notes, payable upon demand, in denominations less than fifty dollars and not less than ten dollars.[6] These were called Demand Notes to distinguish them from the interest-bearing Treasury Notes in existence at the time. The promise to pay specie "on demand" was a new obligation for Treasury Notes (though common on private banknotes) but would spare the cash-strapped treasury the intermediate step of selling an equivalent amount of debt by allowing it to use the notes as a currency to pay creditors directly. The notes were to be redeemable through the assistant treasurers' offices at Philadelphia, Boston, and New York. They were to be hand signed by the first or second comptroller of currency or the Register of the Treasury; they were also supposed to be counter-signed by any other treasury officials designated by the secretary of the treasury. These signature provisions would later be altered several times. This act also stipulated that prior to December 31, 1862, an individual Demand Note could be re-issued into circulation after it was presented for redemption. Just before they were to be released, the Act of August 5, 1861, stipulated several changes to the issuance of Demand Notes.[7] It allowed for Demand Notes to be issued in denominations of not less than $5 and be redeemable through the assistant treasurer's office at St. Louis or the bullion depository in Cincinnati. This act also stated that the Treasurer of the United States and Register of the Treasury or any treasury official appointed by the secretary of the treasury should sign the notes. Under this act, Demand Notes did not need to carry the seal of the U.S. Treasury. This act also granted a traditional privilege of Treasury Notes to the Demand Notes in that they were to be receivable in payment of all public dues, a privilege which was to figure prominently in their eventual disposition. Because the Bureau of Engraving and Printing did not exist at the time, the American Bank Note Company and National Bank Note Company were contracted to create Demand Notes. Both companies were prominent printers of banknotes for private and state-chartered banks throughout the country. Most likely, the American Bank Note Company engraved the printing plates for $5 and $10 notes while the National Bank Note Company engraved the printing plates for the $20 notes. All of the Demand Notes were printed by the American Bank Note Company.[5] As designed, they were of the same size, and in appearance closely resembled banknotes.[8] Post-issuanceSecretary of the Treasury Chase began distributing the notes to meet Union obligations in August 1861. Initially, various merchants, banks and especially the railroad industry accepted the notes at a discounted rate or did not accept them at all. To ease public distrust in the newly issued notes Secretary Chase signed a paper agreeing to accept the notes in payment of his own salary and on September 3, 1861, Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott issued a circular to his soldiers arguing the convenience of the notes for those wishing to send home a portion of their pay.[9] In mid-September[10] Secretary Chase issued the following circular to the assistant treasurers to remove all doubt about the monetary status of the new notes:

These actions also created a willingness on the part of banks to redeem the notes for coin as well. This put Demand Notes on par with the value and purchasing power of gold coins and they circulated widely among the public for private transactions.[5] They could be redeemed for silver coinage as well.[12] The law allowed for the notes to be hand-signed by F. E. Spinner (treasurer) and L. E. Chittenden (register of the Treasury). This proved unfeasible, however, and Congress also authorized the notes to be signed by procurators. Seventy women were hired at an annual salary of $1,200 to sign the notes. A distinction of "for the" was written after a signature to indicate that it was being used in place of treasury officials. Apparently, some skilled women could even imitate the signature of F. E. Spinner.[5] In late August "for the" was added to printing plates to simplify the hand-signing operation. The American Bank Note Company stopped printing notes payable at St. Louis and Cincinnati several days after revising printing plates with "for the".[13] Suspension of specie paymentThe ability of the government to redeem the Demand Notes in specie came under pressure in December 1861. On December 10 Secretary Chase indicated that war expenditures were far exceeding projections while Federal revenues were falling short.[14] Then on the 16th, news of the British reaction to the Trent Affair reached New York and the major banks, which had been supplying gold to the government in exchange for seven-thirties Treasury Notes and bonds which they had been in turn reselling, saw the demand for their offerings of Union securities drop precipitously. By the end of the month the banks had suspended specie payment on their own banknotes. The Demand Notes then began to appear at assistant treasurers' offices in great numbers for redemption,[12] but since the government could not obtain adequate supplies of coin it was forced to follow suit and suspend redeeming the Demand Notes for gold in the first few days of 1862.[9] The transition to legal tender notesThe inability of the Union government to redeem these notes for specie "on demand" caused great concern to Congress in early 1862. Some banks had pledged to make a $150 million loan to the government; the final installment was due on 4 February 1862, and these banks continued to accept Demand Notes for eventual use towards fulfilling this obligation. This supported the value of the notes during January. After February 4, Secretary Chase authorized John Cisco, Assistant U.S. Treasurer in New York City, to accept Demand Notes for short term deposits at five percent interest – thus making the Demand Notes as good as interest bearing deposits, but with the credit of the government.[9] New York banks quickly made the certificates of such deposits their clearing standard. The Demand Notes became the unit of account for dollar denominated obligations in place of gold, which had begun to disappear from circulation, having risen to a 1 to 2% premium over paper. Debate in Congress had turned towards meeting the demand obligation by declaring the notes legal tender – thus obligating all parties to accept them as payment-in-full for contracted debt. While this debate was on-going the cash needs of the government called and the Act of February 12, 1862, authorized an additional $10,000,000 in Demand Notes.[15] This act brought the final possible amount of Demand Notes that could be issued to a sum of $60,000,000 (by April the full $60,000,000 in Demand Notes had been issued). Eventually Congress decided to authorize $150,000,000 of Legal Tender Notes, also known as United States Notes, with the act of February 25, 1862.[16] These were to be a new issue of U.S. currency, part of which were to replace the existing Demand Notes as those were redeemed. The new law, also known as the First Legal Tender Act, granted legal tender status to the new United States Notes except for the purposes of paying duties on imports and interest on U.S. debt. The government promised to continue paying the interest on its debt in coin, and it would accept only coin or Demand Notes in payment of customs duties. The obverse of 1862– and 1863-issue $5, $10, and $20 Legal Tender Notes were very similar in design to the respective Demand Notes, the major changes being the addition of the U.S. Treasury seal and removal of the words "on demand" from the promise to pay. Some confusion existed over the status of the Demand Notes until the act of March 17, 1862, clarified that these were to enjoy legal tender status as well.[17] Thus, Demand Notes were at least as good as Legal Tender Notes, and clearly superior because only the former could be used to pay duties on imports – a major source of revenue to the Union government. As a result, Assistant Treasurer Cisco announced that he reserved the right to redeem future 5% short term deposits of Demand Notes in the new Legal Tender Notes and speculators, foreseeing the higher value of Demand Notes, removed them from circulation as the new notes began to circulate during April.[9] Once in circulation the Legal Tender Notes became the unit of account for prices in dollars – both gold and the hoarded Demand Notes were quoted in terms of them. In May the war began to turn against the Union and hopes for a quick end to hostilities were abandoned. As the year progressed the price of gold rose as the hoarding of commodities began in earnest. Eventually silver and even copper coins disappeared from circulation.[12] As early as the second week of May the Demand Notes were being quoted at a premium for sale to importers who used them in place of gold to pay customs duties.[9] The premium commanded by gold and Demand Notes became a political issue, and in June, Secretary Chase drew criticism by selling $2.25 worth of 7.3% interest bearing Treasury Notes, seven-thirties, for Demand Notes at a three percent premium to par, which were immediately resold by the buyers for a six percent premium in legal tender.[18] While this action allowed Secretary Chase to achieve two important goals, distributing the seven-thirties debt and retiring Demand Notes, it amounted to an official acknowledgement that the new United States Notes had depreciated compared to the Demand Notes. By mid-summer gold dollars were trading for a fifteen percent premium to legal tender while Demand Notes were available for an eight percent premium, and newspapers were reporting the price of Demand Notes under the description "United States Notes for Custom-House Purposes" or "Custom-House Notes".[19] As customs duties averaged $6 to 9 million/month the slow drain of outstanding Demand Notes was tracked in the financial columns.[20] By December it was estimated that the supply would soon be exhausted and that importers would have no option but gold for paying import duties.[21] When the supply of Demand Notes had been nearly exhausted they commanded a price at parity with or at only a slight discount to gold dollars[9] despite the fact that the latter continued to command a steep premium to United States Notes through the 1870s. By June 30, 1863, only $3,300,000 of Demand Notes were outstanding versus almost $400,000,000 of Legal Tender Notes.[9] By June 30, 1883 just $58,985 remained on the books of the treasury.[22] Design

Common features among denominationsThe obverses of all denominations Demand Notes contained the following common features printed on them:

The reverses of all Demand Notes contained "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA", a large numeral of the denomination, and an indication of the denomination (as a small numeral or Roman numeral) repeated many times in a small geometric shape; all of the reverses were printed in green ink.[5] Common varieties among denominations

$5 notesFive dollar Demand Notes feature a small portrait of Alexander Hamilton at the lower right of the note. On the left is the "Statue of Freedom" that sits atop the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington D.C. However, at the time of issue, the "Statue of Freedom" was a work in progress and was not completed until 1862 and was not placed atop the Capitol dome until 1863. The base of the statue reads "E PLURIBUS UNUM", but only "RIBUS UNUM" is visible on the note. The border of the note features the word "FIVE" printed numerous times horizontally at the top, bottom, and right of the note and vertically on the left of the note. The issuing bank note company was printed in middle of the top border and the phrase "RECEIVABLE IN PAYMENT OF ALL PUBLIC DUES." was printed in the middle of the bottom border. There are several common features that are formatted uniquely on $5 Demand Notes. The date, left of Hamilton's portrait, is formatted specifically as "aug. 10th 1861". Also, "ON DEMAND" appears after "FIVE DOLLARS" so that the full statement reads, "THE United States PROMISE TO PAY TO THE BEARER FIVE DOLLARS ON DEMAND". Unlike $10 and $20 notes, five-dollar Demand Notes have the phrase "Payable by the Assistant Treasurer AT [location]" printed, unbound and in full, in a cursive font. Also unlike the $10 and $20 Demand Notes, $5 notes redeemable at Philadelphia have the location written out in full. The reverse of the $5 note contains a small numeral 5 inside of a small oval that is repeated numerous times; this design element surrounded the main design elements of the reverse of the note.[23] $10 notesTen dollar Demand Notes feature a portrait of Abraham Lincoln at left and an allegorical figure representing art to the right. In the top center of the note is a vignette of a bald eagle perched on olive branches with a ribbon stating E PLURIBUS UNUM. Next to the bald eagle is a heraldic stars and stripes shield. Both the portrait of Lincoln and bald eagle vignette were stock elements used on previous banknotes issued by the American Bank Note Company. The border of the note contains the Roman numeral X around almost the entire note. Like the $5 Demand Notes, the issuing bank note company was printed in middle of the top border and the phrase "RECEIVABLE IN PAYMENT OF ALL PUBLIC DUES." was printed in the middle of the bottom border. The top corners of the note contained two small numeral 10s surrounded by an ornate design. The vertical border design, along with the numeral 10s in the corners were stock elements used on other notes made by the American Bank Note Company. In fact, this stock element along with the portrait of Lincoln were also used on a later $10 bill from the Rutland County Bank of Vermont. The $10 Demand Note too, has uniquely formatted common features. The date at the top right of the note is formatted as "August 10, 1861." in a cursive font. Unlike the $5 Demand Notes, "ON DEMAND" appears before "UNITED STATES" so that the statement reads, "ON DEMAND, THE UNITED STATES Promises to Pay to the Bearer TEN DOLLARS"; the middle portion of the statement was printed in a cursive font. The phrase stating the location of payment on most notes was abbreviated to "PAYABLE BY THE ASST. TREASURER OF THE U.S. AT [location]", the exception being Cincinnati where "DEPOSITARY" replaced "ASST. TREASURER". The reverse of the $10 note contains many instances of the small Roman numeral X, each inside of a small square; the main elements of the reverse of the note were superimposed over this.[23] $20 notesTwenty dollar Demand Notes, unlike the $5 and $10 notes, do not feature a portrait of a person. Instead, they feature a feminine allegory attributed either as representing Liberty, or perhaps America,[24] in the center of the note. The figure has a sword in her right hand and holds a striped shield that features a bald eagle at the top of the shield in her left. A large green numeral 2 and 0 are located respectively to her right and left. The border of the note features the word "TWENTY" repeated numerous times horizontally on the top and bottom borders and vertically on the left and right borders. Also unlike the $5 and $10 notes, "ACT OF JULY 17, 1861" is located in the middle of the top border. The very middle of the bottom border contains the issuing bank note company, while "RECEIVABLE IN PAYMENT" is to the left and "OF ALL PUBLIC DUES" is to the right of this. The date on the note is formatted as "August 10th 1861" in a cursive font; the A in "August" has a form resembling lower case. The statement of payment is formatted the same and surrounded by the same engraved object as the $10 Demand Note and is located in the center of the note under the figure of Liberty. The demand statement is printed as "ON DEMAND THE UNITED STATES Promise To Pay Twenty Dollars To the Bearer". The reverse of the $20 Demand Note contains a small numeral 20 inside of an oval that is surrounded by an eight-sided star; all of this is located around the shield-shaped object with the numeral 20 in it. The top and bottom borders feature geometrical design elements with "UNITED STATES" printed horizontally in every other geometric shape.[5] Production figures and collectibilityDemand Notes are no longer found in circulation, but are instead in the hands of collectors. Of the surviving Demand Notes, the vast majority are $5 and $10 notes with "For the" engraved on them and from the locations of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. No notes are known with the actual signatures of F. E. Spinner and L. E. Chittenden. Because of their rarity, Demand Notes are mainly collected by acquiring a single example of the $5 and $10 denomination. Facsimile reproductions are also available. The price and value of a Demand Note depends primarily on its rarity (which location and whether "for the" is handwritten or engraved) and secondarily on its condition. The more common five-dollar notes usually range in price from $2,000 to $25,000. Ten dollar notes of the more common varieties usually have a value range of $4,000 to $30,000. Price ranges of the twenty dollar notes with "for the" engraved and from New York, Boston, and Philadelphia usually vary from $40,000 up to $100,000. Notes of any denomination with "for the" handwritten change hands at prices between $30,000 and $60,000. Notes from Cincinnati and St. Louis only very rarely change hands. Apart from the more common types, Demand Notes are usually only available for sale at auction.

Notes:

See alsoReferences

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||