|

Deinacrida parva

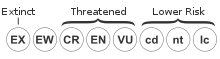

Deinacrida parva is a species of insect in the family Anostostomatidae, the king crickets and weta. It is known commonly as the Kaikoura wētā[1] or Kaikoura giant wētā.[2] It was first described in 1894 from a male individual[3] then rediscovered in 1966 by Dr J.C. Watt at Lake Sedgemore in Upper Wairau.[4] It is endemic to New Zealand, where it can be found in the northern half of the South Island.[2] This is a small to medium-sized robust wētā.[5] It is easily confused with Deinacrida rugosa.[2][6][7] Due to the rarity of this weta, there is still much to be learnt.[8] Description Deinacrida parva have a rounded brown body.[9] The females are larger than the males in this species of wētā, but the males have long legs suggesting scramble competition for mates.[10][11] The females have a large spike on the end of their body, this spike is called an ovipositor and is used for laying eggs.[12] The Kaikoura giant wētā can grow up to around 100mm in size[12] and weigh up to 14.5 grams.[13] They have a life span of roughly two years.[4] This wētā, although very similar in appearance, is smaller in size than D. rugosa and is a brown colour[10] with darker colouring under the abdomen.[9] Red or pink coloration can also be present on the border of the thoracic shield.[2] A major identification of the Kaikoura Wētā is by counting the six spines present on the lower hind leg.[2] The taxonomic status of D.parva and D. rugosa were investigated.[2] These two are species are morphologically similar and phylogenetically sister species.[14] Habitat and distributionDeinacrida parva are found in many different terrestrial environments[15] but most commonly under large logs on river flats and scrub areas close to the edges of the forests.[2] Large proportions of individuals are found under Mataī logs.[8] Their preference for living close to water ways has resulted in the drowning of some individuals, although this might be linked to infection by internal parasites.[13] D. parva are found between 150 and 1500m above sea level from South Marlborough to Hanmer Springs.[2] These weta are considered subalpine specialists.[16] They are most common surrounding Hapuku and Kowhai river close to Kaikōura (hence the name of these wētā).[2] It is suspected they now occupy less than 10% of their former range.[17] DietDeinacrida parva are herbivorous and feed mainly on the leaves of trees and shrubs.[18] Females of this species have been known to eat carcasses of dead or dying insects for extra protein during breeding season for egg development.[8] BehaviourThis weta, like many of the other weta in New Zealand, is nocturnal.[19] D. parva are able to produce sounds by rubbing tergite spines and hair sensilla together (located on their abdominal plates).[5] The sounds are normally produced during contraction of the abdomen and often in time with a defensive leg kick as a warning.[5] This is called the tergo-tergal mechanism.[5] The sounds produced are a soft hiss and often fall within ultrasonic frequencies.[5] Using hair sensilla for sound production is a rare occurrence in arthropods and a potential explanation for why it has occurred in this species is that it has evolved under predation pressure by the endemic short-tailed bat in New Zealand.[5] There are no current evidence that the sounds produced are for intraspecific communication but it has not been researched extensively.[5] BreedingD. parva have been breed in captivity.[2] But due to wētā being captured at different ages and conditions, breeding pairs were hard to establish.[4] Young wētā come to sexual maturity successfully in captivity but some fail to lay eggs.[8] Females lay eggs in the soil with an ovipositor.[12] ConservationPopulations in some parts have declined to a few individuals.[2] Many of the die-offs have been in the large populations close to Kaikoura.[2] Even though there has been a die off the population is considered to be stable.[17] A major reason for decline is likely due to habitat clearance and predation by pests.[2] The changes in the natural habitat of D. parva has affected the chances of future survival in many of the smaller recorded populations.[2] Many of their original habitats have been cleared for pasture.[4] The die-offs could be associated with the Gordian worm parasite.[2] But the full impact of the parasite is unknown and still requires further research.[8] D. parva that become hosts for the Gordian worm parasite have been shown to have lowered reproductive capabilities.[8] Further population surveys and full distribution research needs to be conducted for further information.[8] Although that has been difficult due to low population numbers, thick vegetation and uneven grounds.[8] Searching for these weta in the fallen logs (where they are most likely to be found) also damages and degrades the logs quicker and leaves less available habitats for them.[4] It has been proposed that they should be bred and then released on predator-free islands.[8] Mainland habitat management has also been suggested as a conservation plan.[4] References

Wikispecies has information related to Deinacrida parva. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||