|

Death of Kevin Gately

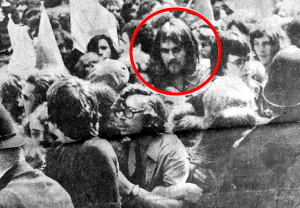

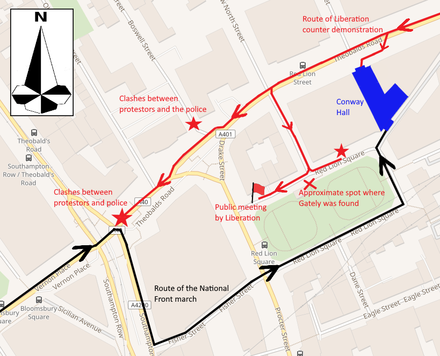

Kevin Gately (18 September 1953 – 15 June 1974) was a student who died as the result of a head injury received in the Red Lion Square disorders in London while protesting against the National Front, a far-right, fascist political party. It is not known if the injury was caused deliberately or was accidental. He was not a member of any political organisation, and the march at Red Lion Square was his first. He was the first person to die in a public demonstration in Great Britain for at least 55 years. On 15 June 1974 the National Front held a march through central London in support of the compulsory repatriation of immigrants. The march was to end at Conway Hall in Red Lion Square. A counter-demonstration was planned by Liberation, an anti-colonial pressure group. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the London council of Liberation had been increasingly infiltrated by hard-left political activists, and they invited several hard-left organisations to join them in the march. When the Liberation march reached Red Lion Square, the International Marxist Group (IMG) twice charged the police cordon blocking access to Conway Hall. Police reinforcements, including mounted police and units of the Special Patrol Group, forced the rioting demonstrators out of the square. As the ranks of people moved away from the square, Gately was found unconscious on the ground. He was taken to hospital and died later that day. Two further disturbances took place in the vicinity, both involving clashes between the police and the IMG contingent. A public inquiry into the events was conducted by Lord Scarman. He found no evidence that Gately had been killed by the police, as had been alleged by some elements of the hard-left press, and concluded that "those who started the riot carry a measure of moral responsibility for his death; and the responsibility is a heavy one".[1] He found fault with some actions of the police on the day. The events in the square made the National Front a household name in the UK, although it is debatable if this had any impact on their share of the vote in subsequent general elections. Although the IMG was heavily criticised by the press and public, there was a rise in localised support and the willingness to demonstrate against the National Front and its policies. There was further violence associated with National Front marches and the counter-demonstrations they faced, including in Birmingham, Manchester, the East End of London (all 1977) and in 1979 in Southall, which led to the death of Blair Peach. After Peach's death, the Labour Party Member of Parliament Syd Bidwell, who had been about to give a speech in Red Lion Square when the violence started, described Peach and Gately as martyrs against fascism and racism. BackgroundLiberation and the National FrontLiberation was formed in 1954 as the Movement for Colonial Freedom, an advocacy group focused on influencing British policy in support of anti-colonial movements in the British Empire.[2] The president of the organisation was Lord Brockway, and two Labour Party members of parliament (MPs) acted as officers.[3] From the early-to-mid-1960s the organisation spent much of its energy in ensuring it was not taken over by members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), a party also dedicated to promoting anti-colonialism.[2] According to the historian Josiah Brownell, despite the organisation's efforts, by 1967 the London Area Council was dominated by CPGB members, including Kay Beauchamp, Tony Gilbert, Dorothy Kuya and Sam Kahn.[4][5] The National Front was founded in 1967 as a far-right, fascist political party.[6] From its inception the organisation had four main issues on which they campaigned: opposition to Britain's membership of the European Economic Community; Ulster; the trade unions and what the journalist Martin Walker calls "the post-immigration attack on black people born in Britain".[7][a] The National Front had grown rapidly in the early 1970s and by 1974 the membership was about 10,000–12,000.[8][9][b] Planning In mid-April 1974 the National Front booked the large theatre room at Conway Hall,[10] a meeting house owned by the Conway Hall Ethical Society in Red Lion Square in central London.[11] The meeting was on the subject "Stop immigration—start repatriation",[12] and was in response to plans by the Labour government to repeal parts of the Immigration Act 1971. The repeal would have given illegal immigrants leave to remain in the UK.[7] The National Front had booked the room for meetings in the previous four years; the meeting in October 1973 had been picketed by demonstrators, leading to scuffles, injuries and arrests. In early May the National Front sent their plans for their march and meeting to the Metropolitan Police. They allowed for 1,500 members on 15 June from Westminster Hall to 10 Downing Street to deliver a petition to Harold Wilson, the prime minister, and then continue to Conway Hall for the meeting.[10] A journalist contacted the London Area Council of Liberation on 4 June and informed them about the National Front's plans.[10] Two days later Liberation called a meeting to arrange a counter-demonstration; among those invited were several hard-left organisations, including the CPGB, International Socialists (IS; later known as the Socialist Workers Party), the Workers Revolutionary Party, Militant Tendency and the International Marxist Group (IMG). As with the National Front, these groups were prepared to use violence against their political opponents;[13] Sir Robert Mark, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in 1974, described the coalition of groups as "not a whit less odious than the National Front".[14] Liberation also booked the smaller assembly room at Conway Hall for 15 June, to coincide with the National Front meeting. The booking caused consternation among some members of Liberation, and with the National Union of Students (NUS), who asked Liberation to cancel the meeting.[10][15] Liberation also planned a demonstration for 15 June, leaving the Victoria Embankment and marching to Red Lion Square to enter Conway Hall.[16] The police discussed the situation with Liberation and asked them to enter the hall for their meeting by the back door in Theobalds Road. The police also agreed the organisation could hold a small open-air meeting in Red Lion Square, which they needed to access from Old North Road, which linked the square and Theobalds Road. Syd Bidwell, a Labour Party MP, was scheduled to address the meeting.[15][17] Liberation had not been involved in political violence, and police did not fear any violence.[16] What Liberation did not know was that the IMG were determined to picket the front entrance of Conway Hall to deny the National Front access.[18] Kevin GatelyKevin Gately was born on 18 September 1953 and was 20 at the time of the disorders at Red Lion Square.[19][20] Originally from Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, he was a mathematics student at the University of Warwick[21] and had never been part of a political demonstration before joining a group of students from Warwick who travelled to London for the day.[22] Gately was 6 feet 7 inches (2.01 m) or 6 feet 9 inches (2.06 m) tall with red hair;[23][24] he is identifiable in several photographs from the day, his head and shoulders clearly above those of his fellow demonstrators.[25] 15 June 1974On 15 June 1974 the police on duty at Red Lion Square were under the control of deputy assistant commissioner John Gerrard. He had allocated four foot-police serials—100 officers—to the National Front march and four to the Liberation march. There were seven foot-police serials in Red Lion Square, plus ten in reserve—two in Dane Street and eight in Bloomsbury Square. Also in reserve were four Special Patrol Group (SPG) units, comprising 112 officers, held near Holborn police station. Two mounted units were also on duty, both in Red Lion Square.[26] In total during the day were 711 foot-police and 25 mounted police;[27] with additional support from traffic and Criminal Investigation Department (CID) officers, there were 923 police deployed to marshal the two marches.[28][29] The SPG was a specialist squad within the Metropolitan Police. It provided a mobile, centrally controlled reserve of uniformed officers which supported local areas, particularly when policing serious crime and civil disturbances.[30] The SPG comprised police officers capable of working as disciplined teams preventing public disorder, targeting areas of serious crime, carrying out stop and searches, or providing a response to terrorist threats.[16][31] Each SPG unit consisted of an inspector, three sergeants and twenty-four officers.[26] Marches to Red Lion Square; first disturbance The National Front marchers—about 900 strong—moved off from their assembly point in Tothill Street at 14:59,[17][32] making their way through Parliament Square and on through the West End of London, arriving at the junction of Vernon Place and Southampton Row at 15:53. They were held there until about 16:00, when they turned right, moved down Southampton Row, turned left into Fisher Street, and then along the south and east sides of Red Lion Square, arriving at the front entrance to Conway Hall at about 16:20.[32] Through the course of their march, they used two groups as "defence parties" ready to defend the column from attack from demonstrators coming from side streets; the march was unmolested throughout the route.[17] The Liberation march comprised between 1,000 and 1,500 people. Most were in their late teens and early twenties; many were students. They left their assembly point on the Embankment at 14:48, making their way via the Strand and High Holborn to arrive at the rear entrance of Conway Hall at 15:33.[16][33] Thirty people left the march at this point and entered the building to take part in the Liberation meeting.[17] The remainder of the marchers continued to the junction with Old North Street, where they turned left and made their way to Red Lion Square, arriving there at 15:36.[32] When the Liberation march arrived in the square, they found a police cordon blocking the way to the left—stopping them accessing the front entrance to Conway Hall. A section of mounted police was lined up behind the cordon. The leading 500 marchers turned to the right, heading towards where the open-air meeting was supposed to take place; as they did so, the IMG, who headed the remainder of the march, slowed their pace, allowing a gap to open with the lead marchers. The marchers at front of the IMG section linked arms and charged round the corner into the police cordon in what the subsequent inquiry called "a deliberate, determined and sustained attack".[34][35] Several missiles and two smoke bombs were thrown at the police, and some of the demonstrators used the staves of their placards or poles of the banners as weapons against the police.[18][36][37] The cordon was bent out of shape, but remained intact. Gerrard called in the two squads of SPG who were on stand-by.[38] Before they arrived, a second surge from the IMG briefly broke through the cordon, bringing marchers into contact with the mounted police. When the SPG arrived, they formed a V-shaped wedge and drove the crowd backwards so the cordon could be re-imposed. The wedge split the demonstrators in two, pushing some back up Old North Street, and some along the north side of the square. The square was cleared of rioters by 15:50—approximately 15 minutes after the first IMG charge on the police cordon—and the SPG continued to press demonstrators from Old North Street back to Theobalds Road.[38][39] During the surge by the SPG, they came into contact with the peaceful demonstrators in the march, driving them apart, as had happened with the IMG contingent. During this action several demonstrators were left on the ground; one of those was Kevin Gately.[16] Because of his height, he was caught on press photographs with fellow students from Warwick; they had been marching behind the IMG group. The last photograph of him alive shows him unscathed, facing up Old North Street and retreating with other students; the photograph was taken before the IMG's second surge towards the police cordon. He was next seen separately by Gerrard and the journalist Peter Chippindale, lying unconscious on the ground as the retreating ranks of people stepped over him. There were no witnesses or other evidence to suggest what happened to Gately between the final photograph and him being on the ground.[40] Gately was picked up by the police and taken to a nearby St John Ambulance post, where he was treated before being taken to University College Hospital; he died four hours later.[16][19] Gately was the first death during a demonstration in Britain for 55 years.[16][41][c] Second disturbance; Southampton RowHaving been moved out of Old North Street, the IMG contingent made their way along Theobalds Road to the junction with Southampton Road. They were held at the crossroads as the National Front march had also arrived at the junction. A cordon of 120–140 police officers stood between the two groups. Twelve mounted police arrived at the spot just before 16:00; fearing a clash between the two sides, they were ordered to drive the Liberation march back down Theobalds Road; the demonstrators were given no prior warning or opportunity to remove themselves before the police moved against them. The retreating demonstrators could not freely make their way back down the road as the police who had driven demonstrators out from Old North Street were blocking the path; blocked in, more violence ensued, with missiles thrown at the police, who used their truncheons freely. According to Richard Clutterbuck, in his examination of political violence in Britain, "newspaper reporters were more critical of the way the police behaved here than in the earlier incident in Red Lion Square itself".[43] Third disturbance; Boswell StreetA small group of IMG members, around 70 in total, formed in Boswell Street, just off Theobalds Road. They were seen by Chief Superintendent Adams who considered them militant and hostile because their arms were linked and appeared to be carrying stakes or batons. He instructed an SPG unit to clear them from the street. His opinion was challenged by several other observers, including two nearby journalists and one of the police sergeants in the SPG unit. The unit advanced into Boswell Street and there was a clash with the IMG members about halfway down the road. Eyewitnesses differ in their accounts as to who was the first of the two groups to offer violence. There were some arrests, which, according to Lord Scarman in his review of the events, "involve[ed] a considerable degree of force".[43][44] At around the time of the Boswell Street clash—16:20—the National Front had been led around the south and east sides of Red Lion Square and into Conway Hall. There was no trouble or contact between the main Liberation march—still having their open-air meeting in the square—and the National Front.[45] Police arrested 51 people during the disturbances, all from the hard-left contingents.[28] Fifty four people reported injuries, 46 of whom were police officers.[46] While the number of reported injuries was low, Scarman noted "many more must have suffered unpleasant injuries of greater or lesser severity which were never reported".[47] AftermathThat evening and in the following weeks, the media reported and commented on the events in the square. Nearly all the mainstream media agreed that the initial clash between marchers and the police was a deliberate attack by the IMG, while many blamed the police for the clash at the junction of Theobalds Road and Southampton Road. One of those newspapers that followed that line was The Guardian, whose headline reported "Left wing deliberately started violence". The report, by Chippindale and Walker, said of the first surge by IMG marchers into the police cordon, "We are in no doubt at all that at this point the marchers around the banner deliberately charged the police cordon".[17][35] The only journalistic sources that blamed the police for the violence were those from the hard-left newspapers; the Socialist Worker carried the headline "Murdered... By Police".[17][48] The post-mortem took place on 16 June 1974 and was conducted by Iain West.[49] He noted some bruising on Gately's face, and one behind the ear: "There was a small roughly oval bruise on the left side of the scalp about 1+1⁄4 inches behind and slightly below the middle of the back of the left ear, 3⁄4 inch in diameter. The bruising extended through all the layers of the scalp."[49] He concluded "Death has resulted from compression of the brain by a large subdural haemorrhage resulting from a head injury ... The bruise ... could have been caused by a blow by or against a hard object, resulting in the formation of a subdural haemorrhage."[50] When later asked what could have caused the bruise, he said "It didn't look particularly like a truncheon injury—it looked more like an object with a rougher surface. That appeared to be the only significant injury on his body ... it seemed most likely to me that he'd been knocked over and struck his head on the curb or been hit by a piece of sawn timber".[51] On 17 June, Bidwell—who was also chairman of the London Council of Liberation—and John Randall, the president of the NUS, separately called for a public inquiry into the conduct of the police.[52] The police welcomed any inquest into the events that took place.[12][53] Gately was buried on 21 June at St Raphael's Church, Surbiton, the church in which he had been baptised. The same day, 500 students, all wearing black armbands, marched through Coventry, the home town of the University of Warwick.[54] To support the call for an inquest, the NUS held a silent march in London on 22 June 1974. The family asked that the marchers did not carry banners, so only one was shown, at the front of the march, that read "Kevin Gately was killed opposing racism and fascism".[22][55] About 8,000 people took part in the march, which was described by the journalist Jeremy Bugler as "a dramatic contrast to last week's battle. Almost completely silent, it was perfectly disciplined".[56] The inquest into Gately's death was opened on 19 June 1974 and adjourned until July. The full hearing took place on 11 and 12 July; because of the public interest in the matter, a jury was appointed. None of the witnesses saw Gately receive any blow to the head.[57][58] One student told the inquest he saw Gately sink to the floor without being hit. "His eyes were closed. I assumed that he had fainted. He was totally unconscious before he hit the ground. He fell sideways as his knees buckled".[58] He tried to reach Gately to help, but was pushed away with the movement of the crowd. The jury reached a verdict of death by misadventure.[58][59] Eighty-two charges were brought against the fifty-one people arrested on the day.[d] Twenty-nine of the charges were dismissed, with fifty-three convictions. No-one was imprisoned, and the penalties were either conditional discharges, being bound over, a fine or a suspended sentence.[46] On 28 June 1974 Roy Jenkins, the Home Secretary, appointed Scarman to conduct a public inquiry into the events in Red Lion Square "to consider whether any lessons may be learned for the better maintenance of public order when demonstrations take place".[60] Jenkins determined that the inquiry would take place after the inquest had concluded.[61] Scarman Inquiry The Scarman inquiry into the events sat for 23 days between 2 September and 2 October; 57 witnesses gave evidence, comprising 19 police officers, 17 demonstrators, 12 journalists, 5 residents or by-standers and 4 others. The report was published in February 1975.[60] Scarman interpreted the breaching of the police cordon in Red Lion Square as a riot, from the legal definition of the term, which allowed the police a wider scope of possible responses to take, including the use of reasonable force.[18][62] In regards to Gately's death, he wrote:

As the blame could not be applied to a specific action by the police or a demonstrator, he concluded "That is why, in my judgement, those who started the riot carry a measure of moral responsibility for his death; and the responsibility is a heavy one".[1] Scarman criticised the police on some of the tactics used in the day's operation. The clearing of peaceful demonstrators at the junction of Theobalds Road and Southampton Road by mounted police was done without warning.[64] He wrote "Public order is an exercise in public relations. ... It may have caused less ... alarm if a warning had been given to the effect that the police required to disperse."[65] The situation was worsened by the presence of police behind those at the junction, which obstructed the avenue of retreat for those trying to avoid the police horses.[66] Scarman also criticised the police for allowing the two marches get too close to each other. Clutterbuck observes that the police were probably reliant on an out-dated view of Liberation, which had not taken into account their takeover by hard-left elements.[66] In October 1975, after Scarman had finished taking evidence but before his findings were published, the NUS published the booklet "The Myth of Red Lion Square". In it, they wrote Gately "died as a direct result of a police attack using batons and horses".[67] Scarman thought the publication prior to his findings was "an affront to the inquiry"; he was troubled by the fact that William Wilson, the MP for Coventry South East, had provided an introduction for the book.[61] LegacyFor the remainder of the 1970s, Liberation found their ability to lead demonstrations against the National Front was diminished, partly because of Red Lion Square, and partly because their agenda was focused on abolishing imperialism and neo-colonialism.[68][69] The IMG was heavily criticised in the public domain for the violence in Red Lion Square. The organisation also received condemnation from the CPGB, as, they said, the violence made it difficult for the anti-fascist movement to broaden its appeal.[70] The IMG no longer relied on mass demonstrations to get their message across, and subsequent opposition to National Front marches was led by the Socialist Workers Party.[42] The events helped make the National Front a household name in the UK.[36][71] News reports showed the National Front standing waiting for police directions, while violence was taking place between the hard-left elements and the police. Walker, in his study of the organisation, states that "it was the NF which emerged as the innocent victims of political violence, the Left who emerged as the instigators, and it was a 21-year-old [sic] student who died."[71] According to Clutterbuck, "the result was precisely what the NF would have wished—publicity for the purpose of their demonstration, discrediting of their detractors, increasing applications for their membership and a substantially increased vote both at the next General Election and at subsequent by-elections".[25] The academic Stan Taylor disputes Clutterbuck's conclusion that the events helped the National Front at the October 1974 general election as, although they raised their vote in some seats, their share of the national vote remained consistent.[72] Despite the blame for Gately's death and the violence of the day being levelled at the hard-left protesters—both in Scarman's report and the media—the number of demonstrators against the National Front and racist policies rose at local levels in the UK through the 1970s.[68] Local demonstrations disrupted election addresses by National Front candidates in the October 1974 election, there was an increase in the amount of literature against them and their policies, and National Front demonstrations through the rest of the 1970s attracted large counter-demonstrations.[73] The increasingly provocative actions by the National Front continued through the 1970s and led to what Peter Waddington, an academic in policing and social policy, describes as "a predictably violent response" from the militant left—violence from both sides was evident in Birmingham, Manchester, the East End of London (all 1977) and in 1979 in Southall, which led to the death of Blair Peach.[74] Following the death of Peach, Bidwell said in Parliament "Blair Peach, together with young Kevin Gately, who died in 1974 in the Red Lion Square events, will be regarded by history as a martyr and a young courageous campaigner against fascism and racism".[75] The University of Warwick have a collection of documents relating to the aftermath of Gately's death.[76] In 2019 the university's student union named one of its meeting rooms after Gately. The union have a mural commemorating him in their main building.[77] See alsoNotes and referencesNotes

References

SourcesBooks

Journals and magazines

News

Websites

Other

|