|

David S. Shellabarger

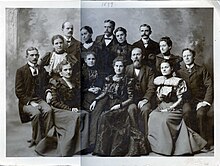

David Sterritt Shellabarger Jr. (July 11, 1837- January 2, 1913), known also as D.S. Shellabarger, was an American capitalist, banker, and Republican politician from Illinois.[1] He was known for owning early banking, coal, streetcar, elevator and milling enterprises in the 19th century.[2] The Shellabarger family was one of the oldest milling families in the history of the United States, beginning their enterprise in 1776.[3]: 132 [4] In 1900, his business Shellabarger Milling Co. became the largest corn mill in the world and among the largest wheat flour mills in the United States.[5] Life David Sterritt Shellabarger Jr. was born on July 11, 1837, to David Sr. and Catharine (née Burly) Shellabarger in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. David Sterritt Shellabarger Sr.'s great-grandfather lived near Lucerne in Switzerland while his maternal great-grandfather was from Germany but later settled in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. David Sr.'s father Isaac emigrated from Switzerland during the British colonization of the Americas in 1763, and began the Shellabarger family milling enterprise.[6][7]: 6 David Sr. continued the milling work, along with his brothers Isaac and John.[8][6] In 1855, 18 year old David Jr. was eager to travel and find more business opportunities, following the openness of The West due to new railroads. He persuaded his father for a loan and blessing to travel by train to Decatur, Illinois, as David Sr.'s brothers had already made the pioneering trip to the new city. Upon arrival in Decatur, David began working for his uncle Isaac in the lumber business.[6] Personal life and deathDavid married Anna E. Krone, a daughter of pioneer David Krone, in Decatur. They married on January 7, 1862, and had eight children until Anne's death in Salina, Kansas. David died in Red Bluff, California in 1913.[9][10] CareerMilling and Elevator careerShellabarger arrived in Decatur, Illinois, in 1856 with a loan from his father.[11]: 4 He subsequently bought a one-third milling interest of Henkle, Shellabarger and Co. In 1859, Shellabarger sold his interest, and used the proceeds to buy The Great Western Mill, changing the name to Shellabarger Mill. He incorporated the business as the Shellabarger Mill & Elevator Co. in 1888 for $250,000, giving each of his three sons a one-sixth interest in the capital stock.[12] Shellabarger was progressive and quick to adopt new inventions with his mills for both increased productivity and safety for his employees.[13][14]: 34 He bought grains from the Midwest farmers,[15] and was the first in Illinois to adopt the roller system and the GEO T Smith purifiers.[16] As more farmland opened in the west, Shellabarger bought elevators and mills across Illinois and Kansas and decreased the milling of wheat to corn.[17] By 1901, his practices produced both large milling capacities and elevator capacity for 250,000 bushels of grain and warehouses capable of storing 10,000 barrels of flour and corn products; an annual business of $2,000,000.[18] In 1902, he sold the Decatur mill property to American Hominy Co., which he formed along Cerealine and eight other western millers. Shellabarger and his sons retained a majority of shares in the company and used the proceeds of the Decatur mill sale to continue building their extensive line of elevators; creating Shellabarger Elevator Co. and establishing Shellabarger Grain Products Co. In 1903, Shellabarger and his sons sold their majority capital stock in American Hominy Co. to solely focus on Shellabarger Elevator Co. and Shellabarger Grain Products Co. By 1910, Shellabarger Elevator Co. owned thirty-five elevators in the country, bringing their total storage capacity to 1,250,000 bushels; more than half of which was fireproof. Their product was known as Shellabarger's Big "S".[19] Due to a mixture of pests (chinch bugs) and continued Prohibition, Shellabarger Grain Products Co., switched entirely from grain and corn milling to soya flour. In 1930 they held the first patent on soybean flour known by the trade name "Diataste". This contributed to the foundation for Decatur's moniker "soybean capital of the world".[20][4][21] In 1938, his son W. L Shellabarger sold Shellabarger Grain Product Co. and all its patents to Spencer Kellogg.[22] Streetcar and coal businessesShellabarger was a pioneer in the streetcar industry, co-founding the first electric streetcar line in Illinois and third in the United States.[23][24] In 1883, Shellabarger as president incorporated the Citizens' Street Railway Company and in 1889, electrified its first line. In 1895, Shellabarger consolidated Citizens, forming City Electric Railway Company and built the current Transfer House to serve as Decatur's main transfer point for City Electric Railway streetcars and Illinois Traction System interurban trains. In 1899 Shellabarger organized the company under the name The Decatur Traction and Electric Company which would sell to the W.B McKinley syndicate, Illinois Terminal Railroad in 1903. Shellabarger was also President of the Manufacturers and Consumers Coal Company of Decatur. Since 1902, he acted as president and Director of the Board of the National Bank of Decatur.[8] Politics and civicsAside from his business endeavours, Shellabarger took an interest in political and civic matters. He was dedicated to the Republican Party and when of voting age, his first vote for president was for Abraham Lincoln in 1860. He acted as alderman in 1869, 1870, and 1871. In 1872 he served as mayor of Decatur, creating the first water works for the city. For two terms in 1880 and 1881 he was elected to represent the Decatur township on the board of supervisors and for fifteen years was member and President of the board of education.[25] He was a candidate for Congress in 1904[26] but was defeated for the office by William B. McKinley. Shellabarger was the first to respond when citizens of Decatur were asked to raise $100,000 to meet the offer of James Millikin in establishing the James Millikin University.[27][28] In 1910 his home in Decatur was used as an annex for the city high school.[29] References

Sources

Further reading

|

||||||||||||||