|

David Hall (printer)

David Hall (1714 – December 24, 1772)[a] was a British printer who immigrated from Scotland to America and became an early American printer, publisher and business partner with Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia. He eventually took over Franklin's printing business of producing official documents for the colonial province of Pennsylvania and that of publishing The Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper that Franklin had acquired in 1729. Hall formed his own printing firm in 1766 and formed partnership firms with others. He published material for the colonial government. Family and personal lifeDavid Hall was born in 1714 in Westfield near Edinburgh, Scotland and his father was James Hall.[1][2][3] He married Mary Leacock (Laycock) on January 7, 1748, at Christ Church in Philadelphia. They had four children.[2][3] Two of his sons were William and David Jr., and were taught the printing trade by their father,[4] eventually became partners with William Sellers in 1766,[5] and afterwards the business became William & David Hall. In time it was transferred to William Hall Jr. William Sr, son of Hall, was a member of the Pennsylvania legislature for several years.[1][6] Hall was a member of the St. Andrews Society and printed its documents. He was associated with the Union Library Company that later became part of the Library Company of Philadelphia. In 1762 he was Master of a Mason lodge in Philadelphia. The American Philosophical Society made Hall a member on March 8, 1768. He did not participate except in 1771 when he was a member of a committee to set a selling price for its publication of its transactions, which he published.[7] He was a donator to the Pennsylvania Hospital, the College of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Contributorship fire insurance company,[8] and the Philadelphia Silk Society.[7] Early lifeHall was apprenticed in 1729 for five years at the age of 15 to a printing firm in Scotland run by John Mosman and William Brown.[3][7] After the training he went to London and obtained a position at Watt's printing business alongside journeyman William Strahan, an acquaintance of Benjamin Franklin.[1] Strahan later became law-printer to the King of England.[9] Hall became a friend of Strahan, who sent a letter on behalf of him to lawyer James Read of Philadelphia, a relative of Deborah Read Franklin,[10] in January 1743 inquiring about opportunities for printers in the American colonies.[3][11] In the letter, Strahan described Hall as a non-drinker, and an honest, hard working, skillful printer that was presently living in his house.[11][12] Read presented the letter to his brother-in-law Franklin,[3][11] who needed an experienced printer[13] to run the Pennsylvania Gazette which he had purchased on October 2, 1729, from Samuel Keimer who had failed to make a success out of the newspaper.[14][15] Franklin sent back a letter to Strahan on July 10 inviting Hall to come to Philadelphia for a job interview. In the letter Franklin said that if Hall did not ultimately like the position offered, he would pay his expenses back to England. Franklin offered Hall a year's employment for the trouble of coming from England and trying the journeyman printer position.[16][b] Hall was 30 years old and accepted Franklin's offer and came to Philadelphia on June 19, 1744, and was employed as a journeyman."[12]

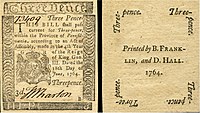

Mid lifeHall adapted well to his new career and learned the Franklin skill techniques of the printing trade. He became a professional in the eighteenth-century printing business which Franklin developed throughout Colonial America.[13][17] According to historian Dumas Malone the finest piece of printing from Franklin's press was published in 1744, Ciero's Cato Maior de Senectute, soon after Hall was employed.[9] Franklin's Poor Richard's Almanack was enlarged soon after that.[9] He became the foreman of Franklin's shop in 1746 at the age of 32 and edited and published Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper.[7] Franklin considered semi-retirement in 1747, since Hall was an active partner.[11] The two drew up on an eighteen-year contract in 1748 where Hall would buy out Franklin's interest in the business.[18][19][20] The printing business became known as the Franklin and Hall firm and among other things were printed almanacs.[2][11][21] Franklin sold the business to Hall for £18,000 (1748) (equivalent to £3.27 million or US$4.07 million in 2023)[22] of which £1,000 (1748) (equivalent to £181,900 or US$226,100 in 2023)[22] was to be paid by Hall annually for 18 years to buy out Franklin's share of the business.[23] At this time the Gazette had an extensive circulation throughout Pennsylvania and neighboring colonies and was a very profitable enterprise; Hall assumed sole management of the newspaper.[24]  Franklin & Hall firm The business sale relieved Franklin of all further trouble about a livelihood and allowed him to devote himself almost exclusively to scientific experiments and other projects.[25] Franklin completed the sale of his part of the printing business to Hall on February 1, 1766.[3][7][26] William Sellers became a journeyman printer for Hall and was a skillful printer. In May 1766, Hall made Sellers a partner in his business.[27] The new firm of Hall and Sellers printed all of the Continental paper money issued by Congress during the American Revolutionary War.[1][6] Hall also printed all the official documents for the government of the province of Pennsylvania and at the same time had a book store that sold books and stationery.[7][6] Business records show that between 1748 and 1772 Hall bought from Straham in London £30,000 (1760) (equivalent to £5.22 million or US$6.48 million in 2023)[22] worth of books and stationery items.[28] Some of these were used by Franklin and because of this three-way friendship (Hall-Straham-Franklin) it was the basis of the first sustained book-importing enterprise in the middle American colonies.[10] His book merchandise business caused a dramatic and permanent increase in the value of imports into Pennsylvania.[10] Franklin's original printing office, that was the print shop of 'Hall & Sellers', was located at the address then known as No. 53 Market street in downtown Philadelphia. Hall had purchased the property itself from the land owner John Cox in 1759.[29] Benjamin Franklin and David Hall's 1759–1766 ledger Work-Book No. 2 of their print house was discovered in an attic in a New Jersey home in 1928 after missing for nearly a century. Wilberforce Eames of the Department of Manuscripts at the New York Public Library claims that the record book is in the hand-writing of David Hall. It reveals that Franklin was in England on business for the Province of Pennsylvania from the middle of 1757 to the middle of 1762. He returned to Philadelphia in November 1762 and remained in the American colonies until November 1764. He then went back to England and was there until the Spring of 1775, when he came back to the colonies. For most of time period from 1759 to 1762 the printing business was conducted by Hall since Franklin was gone. Most of the entries in the journal are charges for advertisements published in the Pennsylvania Gazette. There are scattered throughout the journal's pages recording of charges for various printing jobs related to political papers between November, 1762, and November, 1764; a time when Franklin was in the colonies between his second and third visits to England. It also shows Franklin was sent by the Pennsylvania Assembly as Minister to England protesting against the 1765 Stamp Act. The ledger shows a charge to the province of Pennsylvania for printing 200 copies of a proclamation for public thanksgiving.[30][31] American RevolutionIn the several years leading up to the American Revolution Hall and other printers used the strong influence of newspapers and pamphlets to publicly challenge Parliamentary colonial policy, especially as it concerned taxation without colonial representation.[32] One of the first Early American historians, David Ramsay, said that, “in establishing American independence, the pen and press had merit equal to that of the sword.”[33] Hall was not one to become involved in controversy too rashly,[34] and did not want the Pennsylvania Gazette to assume partisan proportions.[35] Unlike many other newspapers, its pages were witty and insightful and most often lacked the vitriol of many other publications.[35][36] These sentiments faded, however, upon the enactment of the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts.[37] Hall's view of the Stamp Act was that it likely would make the continuation of the Pennsylvania Gazette an unprofitable enterprise.[37] Before the Stamp Act became official Hall received word of its development in Parliament from William Strahan in London,[38] while news of its impending enactment quickly spread through the colonies.[39] Hall warned Franklin that subscribers to their Gazette were cancelling their subscriptions in anticipation of the tax — not over an increase in the cost it would place on the newspaper, but on principle.[37] Hall was also strongly opposed to the passage of the Townshend Acts, and though its provisions did not compromise his printing operations and sales as much as the Stamp Act had, his reaction to it as a patriot printer were just as apprehensive.[40] Hall also employed the Gazette to publish John Dickinson's Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, during the course of several issues.[41] Dickinson's Letters voiced strong sentiment against both the Stamp and Townshend Acts and British colonial policy overall, and its publication in the Gazette and other newspapers played an important role in uniting the colonies.[42][43] Later life and deathHall died at the age of 58 on December 24, 1772,[1][44] and is buried at Christ Church cemetery located at Arch Street and Fifth Street in Philadelphia.[45] Hall's grave is next to where Benjamin Franklin and his wife are buried.[46] WorksExample works printed by Hall. See alsoOther colonial printers:

Notes

References

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||||