|

Crochet

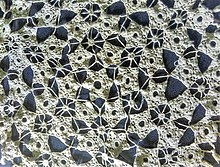

Crochet (English: /kroʊˈʃeɪ/;[1] French: [kʁɔʃɛ][2]) is a process of creating textiles by using a crochet hook to interlock loops of yarn, thread, or strands of other materials.[3] The name is derived from the French term crochet, which means 'hook'.[4] Hooks can be made from different materials (aluminum, steel, metal, wood, bamboo, bone, etc.), sizes, and types (in-line, tapered, ergonomic, etc.). The key difference between crochet and knitting, beyond the implements used for their production, is that each stitch in crochet is completed before you begin the next one, while knitting keeps many stitches open at a time. Some variant forms of crochet, such as Tunisian crochet and Broomstick lace, do keep multiple crochet stitches open at a time. EtymologyThe word crochet is derived from the French word crochet, a diminutive of croche, in turn from the Germanic croc, both meaning "hook".[3] It was used in 17th-century French lace-making, where the term Crochetage designated a stitch used to join separate pieces of lace. The word crochet subsequently came to describe both the specific type of textile, and the hooked needle used to produce it.[5] In 1567, the tailor of Mary, Queen of Scots, Jehan de Compiegne, supplied her with silk thread for sewing and crochet, "soye à coudre et crochetz".[6] Origins Knitted textiles survive from as early as the 11th century CE, but the first substantive evidence of crocheted fabric emerges in Europe during the 19th century.[7] Earlier work identified as crochet was commonly made by nålebinding, a different looped yarn technique.  The first known published instructions for crochet explicitly using that term to describe the craft in its present sense appeared in the Dutch magazine Penélopé in 1823. This includes a colour plate showing five styles of purse, of which three were intended to be crocheted with silk thread.[8] The first is "simple open crochet" (crochet simple ajour), a mesh of chain-stitch arches. The second (illustrated here) starts in a semi-open form (demi jour), where chain-stitch arches alternate with equally long segments of slip-stitch crochet, and closes with a star made with "double-crochet stitches" (dubbelde hekelsteek: double-crochet in British terminology; single-crochet in US).[9] The third purse is made entirely in double-crochet. The instructions prescribe the use of a tambour needle (as illustrated below) and introduce a number of decorative techniques. The earliest dated reference in English to garments made of cloth produced by looping yarn with a hook—shepherd's knitting—is in The Memoirs of a Highland Lady by Elizabeth Grant (1797–1830). The journal entry, itself, is dated 1812 but was not recorded in its subsequently published form until some time between 1845 and 1867, and the actual date of publication was first in 1898.[10] Nonetheless, the 1833 volume of Penélopé describes and illustrates a shepherd's hook, and recommends its use for crochet with coarser yarn.[11] In 1844, one of the numerous books discussing crochet that began to appear in the 1840s states:

Two years later, the same author writes:

An instruction book from 1846 describes Shepherd or single crochet as what in current international terminology is either called single crochet or slip-stitch crochet, with U.S. terminology always using the latter (reserving single crochet for use as noted above).[14] It similarly equates "Double" and "French crochet".[15]  Notwithstanding the categorical assertion of a purely British origin, there is solid evidence of a connection between French tambour embroidery, french passementerie and crochet. A form of hook known as crochet was used to create 'chains in the air' as part of passementerie back in the 17th century. This is confirmed by a patent issued to the passementiers by Louis XIV in 1653, and there are earlier decorative examples of this technique. The patent lists various items, including "thread for embroidery, enhanced and embellished as done with a needle, on thimbles, on the fingers, on a crochet, and on a bobbin." Similarly, chain stitch appears in Queen Elizabeth I's wardrobe accounts, starting in 1558, with further references to garments bordered with 'cheyne lace' in other inventories. One example from 1588 describes "a long cloak of murry velvet, with a border of small cheyne lace of Venice silver." While the exact design of the 1653 crochet is unclear, a 1723 French dictionary by Jacques Savary des Brûlons describes a crochet as a small iron instrument, three or four inches long, with a pointed, curved end and a wooden handle, used by passementiers for tasks like creating hat seams and attaching flowers to mesh. It's most likely that the hook used in crochet came from the ones used by the french pessamenterie industry.[16] French tambour embroidery and the crochet needle used for it was illustrated in detail in 1763 in Diderot's Encyclopedia. The tip of the needle shown there is indistinguishable from that of a present-day inline crochet hook and the chain stitch separated from a cloth support is a fundamental element of the latter technique. The 1823 Penélopé instructions unequivocally state that the tambour tool was used for crochet and the first of the 1840s instruction books uses the terms tambour and crochet as synonyms.[17] This equivalence is retained in the 4th edition of that work, 1847.[18] The strong taper of the shepherd's hook eases the production of slip-stitch crochet but is less amenable to stitches that require multiple loops on the hook at the same time. Early yarn hooks were also continuously tapered but gradually enough to accommodate multiple loops. The design with a cylindrical shaft that is commonplace today was largely reserved for tambour-style steel needles. Both types gradually merged into the modern form that appeared toward the end of the 19th century, including both tapered and cylindrical segments, and the continuously tapered bone hook remained in industrial production until World War II.[citation needed] The early instruction books make frequent reference to the alternative use of 'ivory, bone, or wooden hooks' and 'steel needles in a handle', as appropriate to the stitch being made. [citation needed] Taken with the synonymous labeling of shepherd's- and single crochet, and the similar equivalence of French- and double crochet, there is a strong suggestion that crochet is rooted both in tambour embroidery and shepherd's knitting, leading to thread and yarn crochet respectively; a distinction that is still made. The locus of the fusion of all these elements—the "invention" noted above—has yet to be determined, as does the origin of shepherd's knitting. Shepherd's hooks are still being made for local slip-stitch crochet traditions.[citation needed] The form in the accompanying photograph is typical for contemporary production. A longer continuously tapering design intermediate between it and the 19th-century tapered hook was also in earlier production, commonly being made from the handles of forks and spoons.[citation needed] Irish crochet In the 19th century, as Ireland was facing the Great Irish Famine (1845–1849), crochet lace work was introduced as a form of famine relief[19] (the production of crocheted lace being an alternative way of making money for impoverished Irish workers).[20] Men, women, children joined a co-operative in order to crochet and produce products to help with famine relief during the Great Irish Famine. Schools to teach crocheting were started. Teachers were trained and sent across Ireland to teach this craft. When the Irish immigrated to the Americas, they were able to take with them crocheting.[21] Mademoiselle Riego de la Branchardiere is generally credited with the invention of Irish Crochet, publishing the first book of patterns in 1846. Irish lace became popular in Europe and America, and was made in quantity until the first World War.[22] Modern practice and cultureFashions in crochet changed with the end of the Victorian era in the 1890s. Crocheted laces in the new Edwardian era, peaking between 1910 and 1920, became even more elaborate in texture and complicated stitching.[citation needed]  The strong Victorian colors disappeared, though, and new publications called for white or pale threads, except for fancy purses, which were often crocheted of brightly colored silk and elaborately beaded. After World War I, far fewer crochet patterns were published, and most of them were simplified versions of the early 20th-century patterns.[citation needed] After World War II, from the late 1940s until the early 1960s, there was a resurgence in interest in home crafts, particularly in the United States, with many new and imaginative crochet designs published for colorful doilies, potholders, and other home items, along with updates of earlier publications. These patterns called for thicker threads and yarns than in earlier patterns and included variegated colors. The craft remained primarily a homemaker's art until the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the new generation picked up on crochet and popularized granny squares, a motif worked in the round and incorporating bright colors.   Although crochet underwent a subsequent decline in popularity, the early 21st century has seen a revival of interest in handcrafts and DIY, as well as improvement of the quality and varieties of yarn. As well as books and classes, there are YouTube tutorials and TikTok videos to help people who may need a clearer explanation to learn how to crochet.[23] Filet crochet, Tunisian crochet, tapestry crochet, broomstick lace, hairpin lace, cro-hooking, and Irish crochet are all variants of the basic crochet method.   Crochet has experienced a revival on the catwalk as well. Christopher Kane's Fall 2011 Ready-to-Wear collection[24] makes intensive use of the granny square, one of the most basic of crochet motifs. Websites such as Etsy and Ravelry have made it easier for individual hobbyists to sell and distribute their patterns or projects across the internet. Creating crocheted items has become a way to make sustainable fashion.[25] Fast fashion brands like Shein[26] have created products that resemble crocheted items. MaterialsBasic materials required for crochet are hook, scissors (to cut yarn) and some type of material that will be crocheted, most commonly used are yarn or thread. Alternatively, some choose to crochet with their hands, especially for large yarns. Yarn, one of the most commonly used materials for crocheting, has varying weights which need to be taken into consideration when following patterns. The weight of the yarn can affect not only the look of the product but also the feeling. Acrylic can also be used when crocheting, as it is synthetic and an alternative for wool. Additional tools are convenient for making related accessories. Examples of such tools include cardboard cutouts, which can be used to make tassels, fringe, and many other items; a pom-pom circle, used to make pom-poms; a tape measure and a gauge measure, both used for measuring crocheted work and counting stitches; a row counter; and occasionally plastic rings, which are used for special projects. In recent years, yarn selections have moved beyond synthetic and plant and animal-based fibers to include bamboo, qiviut, hemp, and banana stalks, to name a few. Many advanced crocheters have also incorporated recycled materials into their work in an effort to "go green" and experiment with new textures by using items such as plastic bags, old t-shirts or sheets, VCR or Cassette tape, and ribbon.[27] Crochet hook The crochet hook comes in many sizes and materials. Because sizing is categorized by the diameter of the hook's shaft, a crafter aims to create stitches of a certain size in order to reach a particular gauge specified in a given pattern. If gauge is not reached with one hook, another is used until the stitches made are the needed size. Crafters may have a preference for one type of hook material over another due to aesthetic appeal, yarn glide, or hand disorders such as arthritis, where bamboo or wood hooks are favored over metal for the perceived warmth and flexibility during use. Hook grips and ergonomic hook handles are also available to assist crafters. Aluminum, bamboo, and plastic crochet hooks are available from 2.25 to 30 millimeters in size, or from B-1 to T/X in American sizing.[28] Artisan-made hooks are often made of hand-turned woods, sometimes decorated with semi-precious stones or beads. Steel crochet hooks are sized in a reverse manner – the higher the number, the smaller the hook. They range in size from 0.9 to 2.7 millimeters, or from 14 to 00 in American sizing.[28] These hooks are used for fine crochet work such as doilies and lace. Crochet hooks used for Tunisian crochet are elongated and have a stopper at the end of the handle, while double-ended crochet hooks have a hook on both ends of the handle. Tunisian crochet hooks are shaped without a fat thumb grip and thus can hold many loops on the hook at a time without stretching some to different heights than others (Solovan). There is also a double hooked tool called a Cro-hook. While this is not in itself a hook, it is a device used in conjunction with a crochet hook to produce stitches. Yarn Yarn for crochet is usually sold as balls, or skeins (hanks), although it may also be wound on spools or cones. Skeins and balls are generally sold with a yarn band, a label that describes the yarn's weight, length, dye lot, fiber content, washing instructions, suggested needle size, likely gauge, etc. It is a common practice to save the yarn band for future reference, especially if additional skeins must be purchased. Crocheters generally ensure that the yarn for a project comes from a single dye lot. The dye lot specifies a group of skeins that were dyed together and thus have precisely the same color; skeins from different dye lots, even if very similar in color, are usually slightly different and may produce a visible stripe when added onto existing work. If insufficient yarn of a single dye lot is bought to complete a project, additional skeins of the same dye lot can sometimes be obtained from other yarn stores or online. The thickness or weight of the yarn is a significant factor in determining how many stitches and rows are required to cover a given area for a given stitch pattern. This is also termed the gauge. Thicker yarns generally require large-diameter crochet hooks, whereas thinner yarns may be crocheted with thick or thin hooks. Hence, thicker yarns generally require fewer stitches, and therefore less time, to work up a given project. The recommended gauge for a given ball of yarn can be found on the label that surrounds the skein when buying in stores. Patterns and motifs are coarser with thicker yarns and produce bold visual effects, whereas thinner yarns are best for refined or delicate pattern-work. Yarns are standardly grouped by thickness into six categories: superfine, fine, light, medium, bulky and superbulky. Quantitatively, thickness is measured by the number of wraps per inch (WPI). The related weight per unit length is usually measured in tex or denier.  Before use, hanks are wound into balls in which the yarn emerges from the center, making crocheting easier by preventing the yarn from becoming easily tangled. The winding process may be performed by hand or done with a ball winder and swift.[29] A yarn's usefulness is judged by several factors, such as its loft (its ability to trap air), its resilience (elasticity under tension), its washability and colorfastness, its hand (its feel, particularly softness vs. scratchiness), its durability against abrasion, its resistance to pilling, its hairiness (fuzziness), its tendency to twist or untwist, its overall weight and drape, its blocking and felting qualities, its comfort (breathability, moisture absorption, wicking properties) and its appearance, which includes its color, sheen, smoothness and ornamental features. Other factors include allergenicity, speed of drying, resistance to chemicals, moths, and mildew, melting point and flammability, retention of static electricity, and the propensity to accept dyes. Desirable properties may vary for different projects, so there is no one "best" yarn.  Although crochet may be done with ribbons, metal wire or more exotic filaments, most yarns are made by spinning fibers. In spinning, the fibers are twisted so that the yarn resists breaking under tension; the twisting may be done in either direction, resulting in a Z-twist or S-twist yarn. If the fibers are first aligned by combing them and the spinner uses a worsted type drafting method such as the short forward draw, the yarn is smoother and called a worsted; by contrast, if the fibers are carded but not combed and the spinner uses a woolen drafting method such as the long backward draw, the yarn is fuzzier and called woolen-spun. The fibers making up a yarn may be continuous filament fibers such as silk and many synthetics, or they may be staples (fibers of an average length, typically a few inches); naturally filament fibers are sometimes cut up into staples before spinning. The strength of the spun yarn against breaking is determined by the amount of twist, the length of the fibers and the thickness of the yarn. In general, yarns become stronger with more twist (also called worst), longer fibers and thicker yarns (more fibers); for example, thinner yarns require more twist than do thicker yarns to resist breaking under tension. The thickness of the yarn may vary along its length; a slub is a much thicker section in which a mass of fibers is incorporated into the yarn.[citation needed] The spun fibers are generally divided into animal fibers, plant and synthetic fibers. These fiber types are chemically different, corresponding to proteins, carbohydrates and synthetic polymers, respectively. Animal fibers include silk, but generally are long hairs of animals such as sheep (wool), goat (angora, or cashmere goat), rabbit (angora), llama, alpaca, dog, cat, camel, yak, and muskox (qiviut). Plants used for fibers include cotton, flax (for linen), bamboo, ramie, hemp, jute, nettle, raffia, yucca, coconut husk, banana trees, soy and corn. Rayon and acetate fibers are also produced from cellulose mainly derived from trees. Common synthetic fibers include acrylics,[30] polyesters such as dacron and ingeo, nylon and other polyamides, and olefins such as polypropylene. Of these types, wool is generally favored for crochet, chiefly owing to its superior elasticity, warmth and (sometimes) felting; however, wool is generally less convenient to clean and some people are allergic to it. It is also common to blend different fibers in the yarn, e.g., 85% alpaca and 15% silk. Even within a type of fiber, there can be great variety in the length and thickness of the fibers; for example, Merino wool and Egyptian cotton are favored because they produce exceptionally long, thin (fine) fibers for their type.[citation needed] A single spun yarn may be crochet as is, or braided or plied with another. In plying, two or more yarns are spun together, almost always in the opposite sense from which they were spun individually; for example, two Z-twist yarns are usually plied with an S-twist. The opposing twist relieves some of the yarns' tendency to curl up and produces a thicker, balanced yarn. Plied yarns may themselves be plied together, producing cabled yarns or multi-stranded yarns. Sometimes, the yarns being plied are fed at different rates, so that one yarn loops around the other, as in bouclé. The single yarns may be dyed separately before plying, or afterwards to give the yarn a uniform look.[citation needed] The dyeing of yarns is a complex art. Yarns need not be dyed; or they may be dyed one color, or a great variety of colors. Dyeing may be done industrially, by hand or even hand-painted onto the yarn. A great variety of synthetic dyes have been developed since the synthesis of indigo dye in the mid-19th century; however, natural dyes are also possible, although they are generally less brilliant. The color-scheme of a yarn is sometimes called its colorway. Variegated yarns can produce interesting visual effects, such as diagonal stripes.[citation needed] Process  Crocheted fabric is begun by placing a slip-knot loop on the hook (though other methods, such as a magic ring or simple folding over of the yarn may be used), pulling another loop through the first loop, and repeating this process to create a chain of a suitable length. The chain is either turned and worked in rows, or joined to the beginning of the row with a slip stitch and worked in rounds. Rounds can also be created by working many stitches into a single loop. Stitches are made by pulling one or more loops through each loop of the chain. At any one time at the end of a stitch, there is only one loop left on the hook. Tunisian crochet, however, draws all of the loops for an entire row onto a long hook before working them off one at a time. Like knitting, crochet can be worked either flat (back and forth in rows) or in the round (in spirals, such as when making tubular pieces). [citation needed] Types of stitches There are six main types of basic stitches (the following description uses international crochet terminology with US variants noted in backets).

While the horizontal distance covered by these basic stitches is the same, they differ in height and can be replaced with a length of ch when required, e.g. 1 tr = 3 ch.[31] The more advanced stitches are often combinations of these basic stitches, or are made by inserting the hook into the work in unusual locations. More advanced stitches include the shell stitch, V stitch, spike stitch, Afghan stitch, butterfly stitch, popcorn stitch, cluster stitch, and crocodile stitch. International crochet terms and notations There are two main notations of basic stitches, one used across Europe, Australia, India and other crocheting nations, the other in the US and Canada. (In America, international terminology is often erroneously called British or UK terminology.) Crochet is traditionally worked from a written pattern using standard abbreviations or from a diagram, thus enabling non-English speakers to use English-based patterns.[32] To help counter confusion when reading patterns, a diagramming system using a standard international notation has come into use (illustration, left). In the United States, crochet terminology and sizing guidelines, as well as standards for yarn and hook labeling, are primarily regulated by the Craft Yarn Council.[33]

Another terminological difference is known as tension (international) and gauge (US). Individual crocheters work yarn with a loose or a tight hold and, if unmeasured, these differences can lead to significant size changes in finished garments that have the same number of stitches. In order to control for this inconsistency, printed crochet instructions include a standard for the number of stitches across a standard swatch of fabric. An individual crocheter begins work by producing a test swatch and compensating for any discrepancy by changing to a smaller or larger hook.[35][36] Differences from and similarities to knittingOne of the more obvious differences is that crochet uses one hook while much knitting uses two needles. In most crochet, the artisan usually has only one live stitch on the hook (with the exception being Tunisian crochet), while a knitter keeps an entire row of stitches active simultaneously. Dropped stitches, which can unravel a knitted fabric, rarely interfere with crochet work, due to a second structural difference between knitting and crochet. In knitting, each stitch is supported by the corresponding stitch in the row above and it supports the corresponding stitch in the row below, whereas crochet stitches are only supported by and support the stitches on either side of it. If a stitch in a finished crocheted item breaks, the stitches above and below remain intact, and because of the complex looping of each stitch, the stitches on either side are unlikely to come loose unless heavily stressed.[citation needed] Round or cylindrical patterns are simple to produce with a regular crochet hook, but cylindrical knitting requires either a set of circular needles or three to five special double-ended needles. Many crocheted items are composed of individual motifs which are then joined, either by sewing or crocheting, whereas knitting is usually composed of one fabric, such as entrelac.[citation needed] Freeform crochet is a technique that can create interesting shapes in three dimensions because new stitches can be made independently of previous stitches almost anywhere in the crocheted piece. It is generally accomplished by building shapes or structural elements onto existing crocheted fabric at any place the crafter desires. Knitting can be accomplished by machine, while many crochet stitches can only be crafted by hand. The height of knitted and crocheted stitches is also different: a single crochet stitch is twice the height of a knit stitch in the same yarn size and comparable diameter tools, and a double crochet stitch is about four times the height of a knit stitch.[37] While most crochet is made with a hook, there is also a method of crocheting with a knitting loom. This is called loomchet.[38] Slip stitch crochet is very similar to knitting. Each stitch in slip stitch crochet is formed the same way as a knit or purl stitch which is then bound off. A person working in slip stitch crochet can follow a knitted pattern with knits, purls, and cables, and get a similar result.[39] It is a common perception that crochet produces a thicker fabric than knitting, tends to have less "give" than knitted fabric, and uses approximately a third more yarn for a comparable project than knitted items. Although this is true when comparing a single crochet swatch with a stockinette swatch, both made with the same size yarn and needle/hook, it is not necessarily true for crochet in general. Most crochet uses far less than 1/3 more yarn than knitting for comparable pieces, and a crocheter can get similar feel and drape to knitting by using a larger hook or thinner yarn. Tunisian crochet and slip stitch crochet can in some cases use less yarn than knitting for comparable pieces. According to sources[40] claiming to have tested the 1/3 more yarn assertion, a single crochet stitch (sc) uses approximately the same amount of yarn as knit garter stitch, but more yarn than stockinette stitch. Any stitch using yarnovers uses less yarn than single crochet to produce the same amount of fabric. Cluster stitches, which are in fact multiple stitches worked together, will use the most length.[citation needed] Standard crochet stitches like sc and dc also produce a thicker fabric, more like knit garter stitch. This is part of why they use more yarn. Slip stitch can produce a fabric much like stockinette that is thinner and therefore uses less yarn. Any yarn can be either knitted or crocheted, provided needles or hooks of the correct size are used, but the cord's properties should be taken into account. For example, lofty, thick woolen yarns tend to function better when knitted, which does not crush their airy structure, while thin and tightly spun yarn helps to achieve the firm texture required for Amigurumi crochet.[41]

Charity and activismIt has been very common for people and groups to crochet clothing and other garments and then donate them to soldiers during war. People have also crocheted clothing and then donated it to hospitals, for sick patients and also for newborn babies. Sometimes groups will crochet for a specific charity purpose, such as crocheting for homeless shelters, nursing homes, etc. It is becoming increasingly popular to crochet hats (commonly referred to as "chemo caps") and donate them to cancer treatment centers, for those undergoing chemotherapy and therefore losing hair. During October pink hats and scarves are made and proceeds are donated to breast cancer funds. Organizations dedicated to using crochet as a way to help others include Knots of Love, Crochet for Cancer,[42] and Soldiers' Angels.[43] These organizations offer warm useful items for people in need. In 2020, people around the world banded together to help save the wildlife affected by the Australian bushfires by crocheting kangaroo pouches, koala mittens and wildlife nests.[44] This was an international effort to help during the particularly bad bushfire season which devastated local ecological systems. A group started in 2005 to create crochet versions of coral reefs grew by 2022 to over 20,000 contributors in what became the Crochet Coral Reef Project.[45] To promote awareness of the effects of global warming, their creations have been displayed in galleries and museums by an estimated 2 million people.[45] Many creations apply hyperbolic (curved) geometric shapes—distinguished from Euclidean (flat) geometry—to emulate natural structures.[45] Extending hyperbolic crochet for activism and education with color, a group of South African crafters created The Abundance Crochet Coral Reef, an eco-art installation in Cape Town's Two Oceans Aquarium, to juxtapose hyperbolic shapes crocheted in variations of white on one side of a display with fiber coral shapes crocheted in various colors to illustrate coral bleaching due to oceanic warming and climate change.[46] Feminist scholar-activists have argued for crochet as an embodied method of inquiry aimed at uncovering entangled, relational, and situated ways being and knowing inclusive of the more-than-human co-creation of worlds.[47] In Staying with the Trouble, Donna Haraway argues for the methodological use of crochet to model ecological and mathematical phenomena as "a kind of lure to an affective cognitive ecology stitched in fiber arts" that works "not by mimicry, but by open-ended, exploratory process."[27] Yarn bombingIn recent years, a practice called yarn bombing, or the use of knitted or crocheted cloth to modify and beautify one's (usually outdoor) surroundings, emerged in the US and spread worldwide.[48] Yarn bombers sometimes target existing pieces of graffiti for beautification. In 2010, an entity dubbed "the Midnight Knitter" hit West Cape May. Residents awoke to find knit cozies hugging tree branches and sign poles.[49] In September 2015, Grace Brett was named "The World's Oldest Yarn Bomber". She is part of a group of yarn graffiti-artists called the Souter Stormers, who beautify their local town in Scotland.[50] Mathematics and hyperbolic crochetCrochet has been used to illustrate shapes in hyperbolic space that are difficult to reproduce using other media or are difficult to understand when viewed two-dimensionally.[51] Mathematician Daina Taimiņa first used crochet in 1997 to create strong, durable models of hyperbolic space after finding paper models were delicate and hard to create. These models enable one to turn, fold, and otherwise manipulate space to more fully grasp ideas such as how a line can appear curved in hyperbolic space yet actually be straight. Her work received an exhibition by the Institute For Figuring.[51]  Examples in nature of organisms that show hyperbolic structures include lettuces, sea slugs, flatworms and coral. Margaret Wertheim and Christine Wertheim of the Institute For Figuring created a traveling art installation of a coral reef using Taimina's method. Local artists are encouraged to create their own "satellite reefs" to be included alongside the original display.[52] As hyperbolic and mathematics-based crochet has become more popular, there have been several events highlighting work from various fiber artists. Two shows were Sant Ocean Hall at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., and Sticks, Hooks, and the Mobius: Knit and Crochet Go Cerebral at Lafayette College in Pennsylvania.[53] ArchitectureIn Style in the technical arts, Gottfried Semper looks at the textile with great promise and historical precedent.[clarification needed] In Section 53, he writes of the "loop stitch, or Noeud Coulant: a knot that, if untied, causes the whole system to unravel." In the same section, Semper confesses his ignorance of the subject of crochet but believes strongly that it is a technique of great value as a textile technique and possibly something more. There are a small number of architects currently interested in the subject of crochet as it relates to architecture. The following publications, explorations and thesis projects can be used as a resource to see how crochet is being used within the capacity of architecture.

Styles in crochet

See alsoReferences

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Crochet. |