|

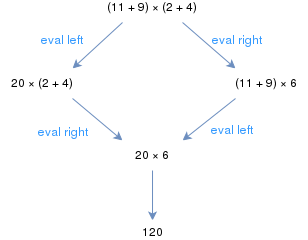

Confluence (abstract rewriting) In computer science and mathematics, confluence is a property of rewriting systems, describing which terms in such a system can be rewritten in more than one way, to yield the same result. This article describes the properties in the most abstract setting of an abstract rewriting system. Motivating examples The usual rules of elementary arithmetic form an abstract rewriting system. For example, the expression (11 + 9) × (2 + 4) can be evaluated starting either at the left or at the right parentheses; however, in both cases the same result is eventually obtained. If every arithmetic expression evaluates to the same result regardless of reduction strategy, the arithmetic rewriting system is said to be ground-confluent. Arithmetic rewriting systems may be confluent or only ground-confluent depending on details of the rewriting system.[1] A second, more abstract example is obtained from the following proof of each group element equalling the inverse of its inverse:[2]

This proof starts from the given group axioms A1–A3, and establishes five propositions R4, R6, R10, R11, and R12, each of them using some earlier ones, and R12 being the main theorem. Some of the proofs require non-obvious, or even creative, steps, like applying axiom A2 in reverse, thereby rewriting "1" to "a−1 ⋅ a" in the first step of R6's proof. One of the historical motivations to develop the theory of term rewriting was to avoid the need for such steps, which are difficult to find by an inexperienced human, let alone by a computer program [citation needed]. If a term rewriting system is confluent and terminating, a straightforward method exists to prove equality between two expressions (also known as terms) s and t: Starting with s, apply equalities[note 1] from left to right as long as possible, eventually obtaining a term s′. Obtain from t a term t′ in a similar way. If both terms s′ and t′ literally agree, then s and t are proven equal. More importantly, if they disagree, then s and t cannot be equal. That is, any two terms s and t that can be proven equal at all can be done so by that method. The success of that method does not depend on a certain sophisticated order in which to apply rewrite rules, as confluence ensures that any sequence of rule applications will eventually lead to the same result (while the termination property ensures that any sequence will eventually reach an end at all). Therefore, if a confluent and terminating term rewriting system can be provided for some equational theory,[note 2] not a tinge of creativity is required to perform proofs of term equality; that task hence becomes amenable to computer programs. Modern approaches handle more general abstract rewriting systems rather than term rewriting systems; the latter are a special case of the former. General case and theory A rewriting system can be expressed as a directed graph in which nodes represent expressions and edges represent rewrites. So, for example, if the expression a can be rewritten into b, then we say that b is a reduct of a (alternatively, a reduces to b, or a is an expansion of b). This is represented using arrow notation; a → b indicates that a reduces to b. Intuitively, this means that the corresponding graph has a directed edge from a to b. If there is a path between two graph nodes c and d, then it forms a reduction sequence. So, for instance, if c → c′ → c′′ → ... → d′ → d, then we can write c d, indicating the existence of a reduction sequence from c to d. Formally, is the reflexive-transitive closure of →. Using the example from the previous paragraph, we have (11+9)×(2+4) → 20×(2+4) and 20×(2+4) → 20×6, so (11+9)×(2+4) 20×6. With this established, confluence can be defined as follows. a ∈ S is deemed confluent if for all pairs b, c ∈ S such that a b and a c, there exists a d ∈ S with b d and c d (denoted ). If every a ∈ S is confluent, we say that → is confluent. This property is also sometimes called the diamond property, after the shape of the diagram shown on the right. Some authors reserve the term diamond property for a variant of the diagram with single reductions everywhere; that is, whenever a → b and a → c, there must exist a d such that b → d and c → d. The single-reduction variant is strictly stronger than the multi-reduction one. Ground confluenceA term rewriting system is ground confluent if every ground term is confluent, that is, every term without variables.[3] Local confluence  An element a ∈ S is said to be locally confluent (or weakly confluent[5]) if for all b, c ∈ S with a → b and a → c there exists d ∈ S with b d and c d. If every a ∈ S is locally confluent, then → is called locally confluent, or having the weak Church–Rosser property. This is different from confluence in that b and c must be reduced from a in one step. In analogy with this, confluence is sometimes referred to as global confluence. The relation , introduced as a notation for reduction sequences, may be viewed as a rewriting system in its own right, whose relation is the reflexive-transitive closure of →. Since a sequence of reduction sequences is again a reduction sequence (or, equivalently, since forming the reflexive-transitive closure is idempotent), = . It follows that → is confluent if and only if is locally confluent. A rewriting system may be locally confluent without being (globally) confluent. Examples are shown in figures 1 and 2. However, Newman's lemma states that if a locally confluent rewriting system has no infinite reduction sequences (in which case it is said to be terminating or strongly normalizing), then it is globally confluent. Church–Rosser propertyA rewriting system is said to possess the Church–Rosser property if and only if implies for all objects x, y. Alonzo Church and J. Barkley Rosser proved in 1936 that lambda calculus has this property;[6] hence the name of the property.[7] (The fact that lambda calculus has this property is also known as the Church–Rosser theorem.) In a rewriting system with the Church–Rosser property the word problem may be reduced to the search for a common successor. In a Church–Rosser system, an object has at most one normal form; that is the normal form of an object is unique if it exists, but it may well not exist. In lambda calculus for instance, the expression (λx.xx)(λx.xx) does not have a normal form because there exists an infinite sequence of β-reductions (λx.xx)(λx.xx) → (λx.xx)(λx.xx) → ...[8] A rewriting system possesses the Church–Rosser property if and only if it is confluent.[9] Because of this equivalence, a fair bit of variation in definitions is encountered in the literature. For instance, in "Terese" the Church–Rosser property and confluence are defined to be synonymous and identical to the definition of confluence presented here; Church–Rosser as defined here remains unnamed, but is given as an equivalent property; this departure from other texts is deliberate.[10] Semi-confluenceThe definition of local confluence differs from that of global confluence in that only elements reached from a given element in a single rewriting step are considered. By considering one element reached in a single step and another element reached by an arbitrary sequence, we arrive at the intermediate concept of semi-confluence: a ∈ S is said to be semi-confluent if for all b, c ∈ S with a → b and a c there exists d ∈ S with b d and c d; if every a ∈ S is semi-confluent, we say that → is semi-confluent. A semi-confluent element need not be confluent, but a semi-confluent rewriting system is necessarily confluent, and a confluent system is trivially semi-confluent. Strong confluenceStrong confluence is another variation on local confluence that allows us to conclude that a rewriting system is globally confluent. An element a ∈ S is said to be strongly confluent if for all b, c ∈ S with a → b and a → c there exists d ∈ S with b d and either c → d or c = d; if every a ∈ S is strongly confluent, we say that → is strongly confluent. A confluent element need not be strongly confluent, but a strongly confluent rewriting system is necessarily confluent. Examples of confluent systems

See alsoNotes

References

External links |