|

Circassian beauty

The concept of Circassian beauty is an ethnic stereotype of the Circassian people. A fairly extensive literary history suggests that Circassian women were thought to be unusually attractive, spirited, smart, and elegant. Therefore, they were seen as mentally and physically desirable for men.[1][2][3] There are folk songs in various languages all around the Middle East and the Balkans describing the unusual beauty of Circassian women. This trend popularised greatly after the Circassian genocide, although the reputation of Circassian women dates back to the Late Middle Ages, when the Circassian coast was frequented by Italian traders from Genoa. This reputation was further reinforced by the Italian banker and politician Cosimo de' Medici (the founder of the Medici dynasty in the Republic of Florence), who conceived an illegitimate son with his Venice-based Circassian slave Maddalena. Additionally, the Circassian women who lived as slaves in the Ottoman harem, the Safavid harem, and the Qajar harem also developed a reputation as extremely beautiful, which then became a common trope of Orientalism throughout the Western world.[4] As a result of this reputation, Circassians in Europe and Northern America were often characterised as ideals of feminine beauty in poetry and art. Consequently, from the 18th century onward, cosmetic products were often advertised by using the word "Circassian" in the title or by claiming that the product was based on substances used by women in Circassia. Many consorts and mothers of the Ottoman Sultans were ethnic Circassians, including, but not limited to: Mahidevran Hatun, Şevkefza Sultan, Rahime Perestu Sultan, Tirimujgan Kadin, Nükhetsezâ Hanim, Hümaşah Sultan, Bedrifelek Kadin, Bidar Kadin, Kamures Kadin, Servetseza Kadin, Bezmiara Kadin, Düzdidil Hanim, Hayranidil Kadin, Meyliservet Kadin, Mihrengiz Kadin, Neşerek Kadin, Nurefsun Kadin, Reftarıdil Kadin, Şayan Kadin, Gevherriz Hanim, Ceylanyar Hanim, Dilfirib Kadin, Nalanıdil Hanim, Nergizev Hanim, and Şehsuvar Kadın. It is likely that many other concubines, whose origin is not recorded, were also of Circassian ethnicity. The "golden age" of Circassian beauty may be considered to be between the 1770s, when the Russian Empire seized the Crimean Khanate and cut off the Black Sea slave trade, which increased the demand for Circassian women in Muslim harems; and the 1860s, when the Russian Empire perpetrated the Circassian genocide and destroyed the Circassians' ancestral homeland during the Russo-Circassian War, creating the modern-day Circassian diaspora. After 1854, almost all concubines in the Ottoman harem were of Circassian origin; the Circassians had been expelled from Russian-controlled lands in the 1860s, and the impoverished refugee parents sold their daughters in a trade that was tolerated despite being formally banned.[5] In the 1860s, the American showman P. T. Barnum exhibited women who he claimed were Circassian beauties. They had a distinctively curly style of big hair, which had no precedent in earlier portrayals of Circassians, but which was soon copied by other female performers, who became known as "moss-haired girls" in the United States. This hairstyle was a sort of exhibit's trademark and was achieved by washing the hair of women in beer, drying it, and then teasing it.[6] It is not clear why Barnum chose this hairstyle; it may have been a reference to the standard Circassian fur hat, rather than the hair. There were also several classical Turkish music pieces and poems praising the beauty of the Circassian ethnic group, such as "Lepiska Saçlı Çerkes" (transl. "Straight, flaxen-haired Circassian"); the word "Lepiska" refers to long and blonde hair that is straight, as if it was flat-ironed. Circassian slave trade From the Middle Ages until the 20th-century, Circassian women were a major target for sexual slavery in the harems of the Islamic Middle East. In the middle ages, the Black Sea slave traders bought slaves from a number of different ethnic groups in the Caucasus, such as Abkhazians, Mingrelians and Circassians.[7] During the early modern Crimean slave trade, the trade of Circassians from the Caucasus expanded and developed in to what was termed a luxury slave trade route, providing elite slaves to the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East.[8][9] The Crimean slave trade was one of the biggest suppliers of concubines (female sex slaves) to the Ottoman Imperial Harem, and virgin slave girls (normally arriving as children) were given to the Sultan from local statesmen, family members, grand dignitaries and provincial governors, and particularly from the Crimean Khan; the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed III received one hundred Circassian virgin girl slaves as presents upon his accession to the throne.[10] When the Crimean slave trade was ended with the Annexation of the Crimean Khanate by the Russian Empire in the 18th-century, the trade of Circassians was redirected from Crimea and went directly from the Caucasus to the Ottoman Empire, developing in to a separate slave trade which continued until the 20th-century.[11] The Circassian slave trade was heavily (though not entirely) focused on slave-girls. In the Islamic empires of the Middle East, enslaved African black women – trafficked via the Trans-Saharan slave trade, the Red Sea slave trade and the Indian Ocean slave trade – were primarily used as domestic house slaves and not exclusively for sexual slavery. Conversely, white women, trafficked via the Black Sea slave trade and the Barbary slave trade, were highly sought after by Middle Eastern Muslim slave traders to be used as concubines (sex slaves) or wives.[12] It was commonly known that Circassian girls were mainly bought to become wives or concubines to rich men, which made the Circassian slave trade to be viewed as a form of marriage market, and it was commonly claimed in these regions that the Circassian girls were in fact eager to be enslaved by the Muslims and asked their parents to sell them to the traders because it was the only way for them to enhance their class status.[13] There was a tendency of apologetism by the Ottomans to claim that slavery was beneficial to the Circassians, since it delivered them from "primitivism to civilisation, from poverty and need to prosperity and happiness", and that they became slaves willingly: "Circassians came to Istanbul willingly 'to become wives of the Sultan and the Pachas, and the young men to become Beys and Pachas'".[14] The Middle East's preference for European white girls over African black girls as sex slaves were noted by the international press, when the slave market was flooded by white girls in the 1850s due to the Circassian genocide, which resulted in the price for white slave girls to become cheaper, and Muslim men, who were not able to buy white girls before, then exchanged their black slave women for white ones. The New York Daily Times reported on August 6, 1856:

There was a greater reluctance from Ottoman authorities to prohibit the Circassian slave trade than the African slave trade, because the Circassian slave trade was regarded as in effect a marriage market, and it continued until the end of the Ottoman Empire after World War I.[11] Girls from Caucasus and the Circassian colonies in Anatolia were still trafficked to other parts of the Middle East, especially the Arab world, in the 1920s; in 1928, at least 60 white slave girls were discovered for sexual purposes in Kuwait.[16] In the 1940s, it was reported that Baluchi girls were shipped via Oman to the rest of the Arabian Peninsula, where they were popular as concubines since Caucasian girls were no longer available, and were sold for $350–450 in Mecca.[17] : 304–307 The legal sex slave trade to the Middle East was ended with the abolition of slavery in Saudi Arabia, slavery in Dubai and slavery in Oman in the 1960s. Literary allusions The legend of Circassian women in the western world was enhanced in 1734, when, in his Letters on the English, Voltaire alludes to the beauty of Circassian women:

Their beauty is mentioned in Henry Fielding's Tom Jones (1749), in which Fielding remarked, "How contemptible would the brightest Circassian beauty, drest in all the jewels of the Indies, appear to my eyes!"[19] Similar claims about Circassian women appear in Lord Byron's Don Juan (1818–1824), in which the tale of a slave auction is told:

The legend of Circassian women was also repeated by legal theorist Gustav Hugo, who wrote that "Even beauty is more likely to be found in a Circassian slave girl than in a beggar girl", referring to the fact that even a slave has some security and safety, but a "free" beggar has none. Hugo's comment was later condemned by Karl Marx in The Philosophical Manifesto of the Historical School of Law (1842) on the grounds that it excused slavery.[20] Mark Twain reported in The Innocents Abroad (1869) that "Circassian and Georgian girls are still sold in Constantinople, but not publicly."[21] American travel author and diplomat Bayard Taylor in 1862 claimed that, "So far as female beauty is concerned, the Circassian women have no superiors. They have preserved in their mountain home the purity of the Grecian models, and still display the perfect physical loveliness, whose type has descended to us in the Venus de' Medici."[22] Circassian featuresCircassian women  An anthropological literary suggests that Circassians were best characterized by what was called "rosy pale" or "translucent white skin". While most Circassian tribes were famous for abundance of fair or dark blond and red hair combined with greyish-blue or green eyes,[23] many also had the pairing of very dark hair with very light complexions, a typical feature of peoples of the Caucasus.[24] Many of the Circassian women in the Ottoman harem were described as having "green eyes and long, dark blond hair, pale skin of translucent white colour, thin waist, slender body structure, and very good-looking hands and feet".[23] The fact that Circassian women were traditionally encouraged to wear corsets in order to keep their posture straight might have shaped their wasp waist as a result. In the late 18th century, it was claimed by Western European couturiers that "the Circassian Corset is the only one which displays, without indelicacy, the shape of the bosom to the greatest possible advantage; gives a width to the chest which is equally conducive to health and elegance of appearance".[25] It has also been suggested that a lithe and erect physique were favored for Circassians, and many villages had large numbers of healthy elderly people, many over a hundred years of age.[26] Maturin Murray Ballou described Circassians as being of the "fair and rosy-cheeked race", and "with a form of ravishing loveliness, large and lustrous eyes, and every belonging that might go to make up a Venus".[27] In Henry Lindlahr's words in the early 20th century, "Blue-eyed Caucasian regiments today form the cream of the Sultan's army. Circassian beauties are admired for their abundant and luxuriant yellow hair and blue eyes."[28] In his book A Year Among the Circassians, John Augustus Longworth describes a Circassian girl of typical Circassian features as the following:

It is also understood from the memoirs of Princess Emily Ruete, a half-Circassian and half-Omani herself, that Circassian women, who were bought in Constantinople and brought via the Circassian slave trade to slavery in Zanzibar for the harem of Zanzibari Said bin Sultan, Sultan of Muscat and Oman, were envied by their rivals who considered Circassians to be of the "hateful race of blue-eyed cats".

Regarding one of her half-sisters who was also from a Circassian mother, Princess Ruete of Zanzibar mentions that "The daughter of a Circassian was a dazzling beauty with the complexion of a German blonde. Besides, she possessed a sharp intellect, which made her into a faithful advisor of my father's."[30] The characteristics of Circassian and Georgian women were further articulated in 1839 by the author Emma Reeve who, as stated by Joan DelPlato, differentiated "between 'the blond Circassians' who are 'indolent and graceful, their voices low and sweet' and what she calls the slightly darker-skinned Georgians who are 'more animated' and have more 'intelligence and vivacity than their delicate rivals'".[31][32] Similar descriptions of the Circassian women appear in Florence Nightingale's travel journal where Nightingale called Circassians "the most graceful and the most sensual-looking creatures I ever saw".[31] According to the feminist Harriet Martineau, Circassians trafficked to slavery in Egypt were the only saving virtue of the Egyptian harem where these Circassian mothers produced the finest children and if they were to be excluded from the harem, the upper class in Egypt would be doomed.[31] The sex slave trade of "white women" (normally Circassians) to the Egyptian harems was explicitly banned after pressure by the British in the Anglo-Egyptian Slave Trade Convention of 1884. In parts of Europe and North America where blond hair was more common, the pairing of extremely white skin with very dark hair also present among some Circassians was exalted, even in Russia which was at war with the Circassians; Semyon Bronevskii exalted Circassian women for having light skin, dark brown hair, dark eyes and "the lineaments of the face of the Ancient Greek".[33] In the United States, the girls disguised as "Circassians" exhibited by Phineas T. Barnum were in fact Catholic Irish girls from Lower Manhattan.[34] Circassian menCircassian men were also exalted for their beauty, manliness, and bravery in Western Europe, in a way Caucasus historian Charles King calls "homoerotic".[35] In Scotland, in 1862, Circassian chiefs arrived to advocate their cause against Russia and to persuade Britain to stop the actions of the Russian army at that time,[36] and upon the arrival of two Circassian leaders, Hadji Hayder Hassan and Kustan Ogli Ismael, the Dundee Advertiser reported that

Pseudoscientific explanations for fair skinDuring the 19th century, various Western intellectuals offered pseudoscientific explanations for the light complexion present among Circassians. The doctor of medicine Hugh Williamson, a signatory to the United States Constitution, argued that the reason for the extreme whiteness of the Circassian and coastal Celto-Germanic peoples can be explained by the geographical location of these folks' ancestral homelands which lie in high latitudes ranging from 45° to 55° N near a sea or ocean where westerlies prevail from the west towards the east.[37]

According to Voltaire, the practice of inoculation (see also variolation, an early form of vaccination) resulted in the Circassians having skin clean of smallpox scars:

Pseudoscientific racialist theoriesBy the early 19th century, Circassians were associated with theories of racial hierarchy, which elevated the Caucasus region as the source of the purest examples of the "white race", which was named the Caucasian race after the area by German physiologist and anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. Blumenbach theorised that the Circassians were the closest to God's original model of humanity, and thus "the purest and most beautiful whites were the Circassians".[39] This fuelled the idea of female Circassian beauty.[40] In 1873, the decade after the expulsion of Circassians from the Caucasus where only a minority of them live today, it was argued that "the Caucasian Race receives its name from the Caucasus, the abode of the Circassians who are said to be the handsomest and best-formed nation, not only of this race, but of the whole human family."[41] Another anthropologist, William Guthrie, distinguished the Caucasian race and the "Circassians who are admired for their beauty" in particular by their oval form of their head, straight nose, thin lips, vertically-placed teeth, facial angle from 80 to 90 degrees that he calls the most developed one, and their regular features overall, which "causes them to be considered as the most handsome and agreeable".[42] American travel writer Bayard Taylor observed Circassian women during his trip to the Ottoman Empire and argued that "the Circassian face is a pure oval; the forehead is low and fair, an excellent thing in woman, and the skin of an ivory whiteness, except the faint pink of the cheeks and the ripe, roseate stain of the lips."[22] Circassians are depicted in images of harems at this time through these ideologies of racial hierarchy. English painter John Frederick Lewis's The Harem portrays Circassians as the dominant mistresses of the harem, who look down on other women, as implied in the review of the painting in The Art Journal, which described it as follows:

Orientalizing paintings of nudes were also sometimes exhibited as "Circassians". The Circassians became major news during the Caucasian War, in which Russia conquered the North Caucasus, displacing large numbers of Circassians southwards. In 1856 The New York Times published a report entitled "Horrible Traffic in Circassian Women – Infanticide in Turkey", asserting that a consequence of the Russian conquest of the Caucasus was an excess of beautiful Circassian women on the Constantinople slave market, and that this was causing prices of slaves in general to plummet.[44] The story drew on ideas of racial hierarchy, stating that:

The article also claimed that children born to the "inferior" black concubines were being killed. This story drew widespread attention to the area, as did later conflicts. At the same time writers and illustrators were also creating images depicting the authentic costumes and people of the Caucasus. Francis Davis Millet depicted Circassian women during his 1877 coverage of the Russo-Turkish war, specifying local costume and hairstyle. Advertising of beauty products An advertisement from 1782 titled "Bloom of Circassia" makes clear that it was by then well established "that the Circassians are the most beautiful Women in the World", but goes on to reveal that they "derive not all their Charms from Nature". They used a concoction supposedly extracted from a vegetable native to Circassia. Knowledge of this "Liquid Bloom" had been brought back by a "well-regarded gentleman" who had traveled and lived in the region. It "instantly gives a Rosy Hue to the Cheeks", a "lively and animated Bloom of Rural Beauty" that would not disappear in perspiration or handkerchiefs.[45] In 1802 "the Balm of Mecca" was also marketed as being used by Circassians: "This delicate as well as fragrant composition has been long celebrated as the summit of cosmetics by all the Circassian and Georgian women in the seraglio of the Grand Sultan". It claims that the product was endorsed by Lady Mary Wortley Montague who stated that it was very helpful "for removing those sebacious impurities so noxious to beauty". The article continues:

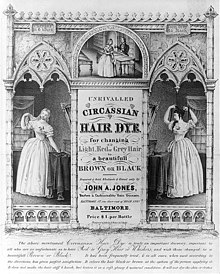

"Circassian Lotion" was sold in 1806 for the skin, at fifty cents the bottle.

"Circassian Eye-Water" was marketed as "a sovereign remedy for all diseases of the eyes",[46] and in the 1840s "Circassian hair dye" was marketed to create a rich dark lustrous effect.[47] Nineteenth-century sideshow attraction The combination of the popular issues of slavery, the Orient, racial ideology, and sexual titillation gave the reports of Circassian women sufficient notoriety at the time that the circus leader P. T. Barnum decided to capitalize on this interest. He displayed a "Circassian Beauty" at his American Museum in 1865. Barnum's Circassian beauties were young women with tall, teased hairstyles, rather like the Afro style of the 1970s.[48] Actual Circassian hairstyles bore no resemblance to Barnum's fantasy.[49] Barnum's first "Circassian" was marketed under the name "Zalumma Agra"[50] and was exhibited at his American Museum in New York from 1864. Barnum had written to John Greenwood, his agent in Europe, asking him to purchase a beautiful Circassian girl to exhibit, or at least to hire a girl who could "pass for" one. However, it seems that "Zalumma Agra" was probably a local girl hired by the show, as were later "Circassians".[51] Barnum also produced a booklet about another of his Circassians, Zoe Meleke, who was portrayed as an ideally beautiful and refined woman who had escaped a life of sexual slavery. The portrayal of a white woman as a rescued slave at the time of the American Civil War played on the racial connotations of slavery at the time. It has been argued that the distinctive hairstyle affiliates the side-show Circassian with African identity, and thus,

The trend spread, with supposedly Circassian women featured in dime museums and travelling medicine shows, sometimes known as "Moss-haired girls". They were typically identified by the distinctive hairstyle, which was held in place by the use of beer. They also often performed in pseudo-oriental costume. Many postcards of Circassians also circulated. Though Barnum's original women were portrayed as proud and genteel, later images of Circassians often emphasised erotic poses and revealing costumes.[48] As the original fad faded, the "Circassians" started to add to their appeal by performing traditional circus tricks such as sword swallowing.[52] In popular culture

See also

References

Further reading

External linksWikisource has original text related to this article:

|