|

Christian eschatology

Christian eschatology is a minor branch of study within Christian theology which deals with the doctrine of the "last things", especially the Second Coming of Christ, or Parousia. The word eschatology derives from two Greek roots meaning "last" (ἔσχατος) and "study" (-λογία) – involves the study of "end things", whether of the end of an individual life, of the end of the age, of the end of the world, or of the nature of the Kingdom of God. Broadly speaking, Christian eschatology focuses on the ultimate destiny of individual souls and of the entire created order, based primarily upon biblical texts within the Old and New Testaments. Christian eschatology looks to study and discuss matters such as death and the afterlife, Heaven and Hell, the Second Coming of Jesus, the resurrection of the dead, the rapture, the tribulation, millennialism, the end of the world, the Last Judgment, and the New Heaven and New Earth in the world to come. Eschatological passages appear in many places in the Bible, in both the Old and New Testaments. Many extra-biblical examples of eschatological prophecies also exist, as well as extra-biblical ecclesiastical traditions relating to the subject. HistoryEschatology within early Christianity originated with the public life and preaching of Jesus.[1] Jesus is sometimes interpreted as referring to his Second Coming in Matthew 24:27; Matthew 24:37–39; Matthew 26:64; Mark 14:62. Christian eschatology is an ancient branch of study in Christian theology, informed by Biblical texts such as the Olivet Discourse (recorded in Matthew 24–25, Mark 13, and Luke 21), The Sheep and the Goats, and other discourses of end times by Jesus, with the doctrine of the Second Coming discussed by Paul the Apostle[2] in his epistles, both the authentic and the disputed ones. Other eschatological doctrines can be found in the Epistle of James,[3] the First Epistle of Peter,[4] and the First Epistle of John.[5] According to some scholars, the Second Epistle of Peter explains that God is patient and has not yet brought about the Second Coming of Christ, in order that more people will have the chance to reject evil and find salvation (3:3–9); therefore, it calls on Christians to wait patiently for the Parousia and to study scripture. Other scholars, however, believe that the New Testament epistles are an exhortation to the early church believers to patiently expect the imminent return of Jesus, predicted by himself on several occasions in the gospels. The First Epistle of Clement, written by Pope Clement I in ca. 95, criticizes those who had doubts about the faith because the Second Coming had, in his view, not yet occurred.[6] Christian eschatology is also discussed by Ignatius of Antioch (c. 35–107 AD) in his epistles,[7] then given more consideration by the Christian apologist, Justin Martyr (c. 100–165).[8] Treatment of eschatology continued in the West in the teachings of Tertullian (c. 160–225), and was given fuller reflection and speculation soon after by Origen (c. 185–254).[9] The word was used first by the Lutheran theologian Abraham Calovius (1612–1686) but only came into general usage in the 19th century.[10] The growing modern interest in eschatology is tied to developments in Anglophone Christianity. Puritans in the 18th and 19th centuries were particularly interested in a postmillennial hope which surrounded Christian conversion.[11] This would be contrasted with the growing interest in premillennialism, advocated by dispensational figures such as J. N. Darby.[12] Both of these strands would have significant influences on the growing interests in eschatology in Christian missions and in Christianity in West Africa and Asia.[13][14] However, in the 20th century, there would be a growing number of German scholars such as Jürgen Moltmann and Wolfhart Pannenberg who would likewise be interested in eschatology.[15] In the 1800s, a group of Christian theologians inclusive of Ellen G. White, William Miller and Joseph Bates began to study eschatological implications revealed in the Book of Daniel and the Book of Revelation. Their interpretation of Christian eschatology resulted in the founding of the Seventh-day Adventist church. Christian eschatological views The following approaches arose from the study of Christianity's most central eschatological document, the Book of Revelation, but the principles embodied in them can be applied to all prophecy in the Bible. They are by no means mutually exclusive and are often combined to form a more complete and coherent interpretation of prophetic passages. Most interpretations fit into one, or a combination, of these approaches. The alternate methods of prophetic interpretation, Futurism and Preterism which came from Jesuit writings, were brought about to oppose the Historicism interpretation which had been used from Biblical times[16][17][18][19] that Reformers used in teaching that the Antichrist was the Papacy or the power of the Roman Catholic Church.[20]  PreterismPreterism is a Christian eschatological view that interprets some (partial preterism) or all (full preterism) prophecies of the Bible as events which have already happened. This school of thought interprets the Book of Daniel as referring to events that happened from the 7th century BC until the first century AD, while seeing the prophecies of Revelation as events that happened in the first century AD. Preterism holds that Ancient Israel finds its continuation or fulfillment in the Christian church at the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70. Historically, preterists and non-preterists have generally agreed that the Jesuit Luis de Alcasar (1554–1613) wrote the first systematic preterist exposition of prophecy, Vestigatio arcani sensus in Apocalypsi (published in 1614), during the Counter-Reformation. HistoricismHistoricism, a type of method of interpretation of biblical prophecies, associates symbols with historical persons, nations or events. It can result in a view of progressive and continuous fulfillment of prophecy covering the period from biblical times to what they view as a possible future Second Coming of Christ. Most Protestant Reformers from the Reformation into the 19th century held historicist views.[21] FuturismIn Futurism, parallels may be drawn with historical events, but most eschatological prophecies are chiefly referring to events which have not yet been fulfilled, but will take place at the end of the age and the end of the world. Most prophecies will be fulfilled during a time of global chaos known as the Great Tribulation and afterwards.[22] Futurist beliefs usually have a close association with Premillennialism and Dispensationalism. IdealismIdealism (also called the spiritual approach, the allegorical approach, the nonliteral approach, and many other names) in Christian eschatology is an interpretation of the Book of Revelation that sees all of the imagery of the book as symbols.[23] Jacob Taubes writes that idealist eschatology came about as Renaissance thinkers began to doubt that the Kingdom of Heaven had been established on earth, or would be established, but still believed in its establishment.[24] Rather than the Kingdom of Heaven being present in society, it is established subjectively for the individual.[24] F. D. Maurice interpreted the Kingdom of Heaven idealistically as a symbol representing society's general improvement, instead of a physical and political kingdom. Karl Barth interprets eschatology as representing existential truths that bring the individual hope, rather than history or future-history.[25] Barth's ideas provided fuel for the Social Gospel philosophy in America, which saw social change not as performing "required" good works, but because the individuals involved felt that Christians could not simply ignore society's problems with future dreams.[26] Different authors have suggested that the Beast represents various social injustices, such as exploitation of workers,[27] wealth, the elite, commerce,[28] materialism, and imperialism.[29] Various Christian anarchists, such as Jacques Ellul, have identified the State and political power as the Beast.[30] Other scholars identify the Beast with the Roman empire of the first century AD, but recognize that the Beast may have significance beyond its identification with Rome. For example, Craig R. Koester says "the vision [of the beast] speaks to the imperial context in which Revelation was composed, but it does so with images that go beyond that context, depicting the powers at work in the world in ways that continue to engage readers of subsequent generations."[31] And his comments on the whore of Babylon are more to the point: "The whore [of Babylon] is Rome, yet more than Rome."[32] It "is the Roman imperial world, which in turn represents the world alienated from God."[33] As Stephen Smalley puts it, the beast represents "the powers of evil which lie behind the kingdoms of this world, and which encourage in society, at any moment in history, compromise with the truth and opposition to the justice and mercy of God."[34] It is distinct from Preterism, Futurism and Historicism in that it does not see any of the prophecies (except in some cases the Second Coming, and Final Judgment) as being fulfilled in a literal, physical, earthly sense either in the past, present or future,[35] and that to interpret the eschatological portions of the Bible in a historical or future-historical fashion is an erroneous understanding.[36] Comparison of Futurist, Preterist and Historicist beliefs

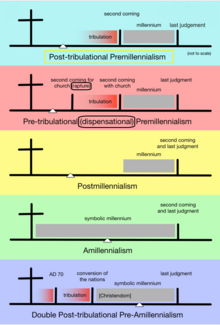

Preterism v. HistoricismExpositors of the traditional Protestant interpretation of Revelation known as Historicism have often maintained that Revelation was written in AD 96 and not AD 70. Edward Bishop Elliott, in the Horae Apocalypticae (1862), argues that John wrote the book in exile on Patmos "at the close of the reign of Domitian; that is near the end of the year 95 or beginning of 96". He notes that Domitian was assassinated in September 96.[65]: 47 Elliot begins his lengthy review of historical evidence by quoting Irenaeus, a disciple of Polycarp. Polycarp was a disciple of the Apostle John. Irenaeus mentions that the Apocalypse was seen "no very long time ago [but] almost in our own age, toward the end of the reign of Domitian".[65]: 32 Other historicists have seen no significance in the date that Revelation was written, and have even held to an early date[66] while Kenneth L. Gentry Jr., makes an exegetical and historical argument for the pre-AD 70 composition of Revelation.[67] Historicism v. FuturismThe division between these interpretations can be somewhat blurred. Most futurists are expecting a rapture of the Church, an antichrist, a Great Tribulation and a second coming of Christ in the near future. But they also accept certain past events, such as the rebirth of the State of Israel and the reunification of Jerusalem as prerequisites to them, in a manner which the earlier historicists have done with other dates. Futurists, who do not normally use the day-year principle, interpret the Prophecy of Seventy Weeks in Daniel 9:24 as years, just as historicists do. Most historicists have chosen timelines, from beginning to end, entirely in the past,[68] but some, such as Adam Clarke, have timelines which also commenced with specific past events, but require a future fulfillment. In his commentary on Daniel 8:14 published in 1831, he stated that the 2,300-year period should be calculated from 334 BC, the year Alexander the Great began his conquest of the Persian Empire.[69] His calculation resulted in the year 1966. He seems to have overlooked the fact that there is no "year zero" between BC and AD dates - that is, the year following 1 BC is 1 AD. Thus his calculations should have required an additional year, ending in 1967. He was not anticipating a literal regathering of the Jewish people prior to the second coming of Christ. But the date is of special significance to futurists since it is the year of Jerusalem's capture by Israeli forces during the Six-Day War. His commentary on Daniel 7:25 contains a 1260-year period commencing in 755 AD and ending in 2015.[69] Major theological positionsPremillennialismPremillennialism can be divided into two common categories: Historic Premillennialism and Dispensational Premillennialism. Historic Premillennialism is usually associated with post-tribulation "rapture" and does not see a strong distinction between ethnic Israel and the Church. Dispensational Premillennialism can be associated with any of the three rapture views but is often associated with a pretribulation rapture. Dispensationalism also sees a stronger distinction between ethnic Israel and the Church. Premillennialism usually posits that Christ's second coming will inaugurate a literal thousand-year earthly kingdom. Christ's return will coincide with a time of great tribulation. At this time, there will be a resurrection of the people of God who have died, and a rapture of the people of God who are still living, and they will meet Christ at his coming. A thousand years of peace will follow (the millennium), during which Christ will reign and Satan will be imprisoned in the Abyss. Those who hold to this view usually fall into one of the following three categories: Pretribulation rapturePretribulationists believe that the second coming will be in two stages separated by a seven-year period of tribulation. At the beginning of the tribulation, true Christians will rise to meet the Lord in the air (the Rapture). Then follows a seven-year period of suffering in which the Antichrist will conquer the world and persecute those who refuse to worship him. At the end of this period, Christ returns to defeat the Antichrist and establish the age of peace. This position is supported by a scripture which says, "God did not appoint us to wrath, but to obtain salvation through our Lord Jesus Christ." [1 Thess 5:9] Midtribulation raptureMidtribulationists believe that the Rapture will take place at the halfway point of the seven-year tribulation, i.e. after 3+1⁄2 years. It coincides with the "abomination of desolation"—a desecration of the temple where the Antichrist puts an end to the Jewish sacrifices, sets up his own image in the temple, and demands that he be worshiped as God. This event begins the second, most intense part of the tribulation. Some interpreters find support for the "midtrib" position by comparing a passage in Paul's epistles with the book of Revelation. Paul says, "We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed" (1 Cor 15:51–52). Revelation divides the great tribulation into four sets of increasingly catastrophic judgments: the Seven Seals, the Seven Trumpets, the Seven Thunders (Rev 10:1–4) and the Seven Bowls, in that order. If the "last trumpet" of Paul is equated with the last trumpet of Revelation and the revelation of the scroll of the Seven Thunders, the Rapture would be in the middle of the Tribulation. (Not all interpreters agree with this literal interpretation of the chronology of Revelation, however.) Posttribulation rapturePosttribulationists hold that Christ will not return until the very end of the seven-year tribulation period. Christians, rather than being raptured at the beginning of the tribulation, or halfway through, will live through it and suffer for their faith during the ascendancy of the Antichrist. Proponents of this position believe that the presence of believers during the tribulation is necessary for a final evangelistic effort during a time when external conditions will combine with the Gospel message to bring great numbers of converts into the Church in time for the beginning of the Millennium. PostmillennialismPostmillennialism is an interpretation of chapter 20 of the Book of Revelation which sees Christ's second coming as occurring after the "Millennium", a Messianic Age in which Christian ethics prosper.[70] The term subsumes several similar views of the end times, and it stands in contrast to premillennialism and, to a lesser extent, amillennialism. Postmillennialism holds that Jesus Christ establishes his kingdom on earth through his preaching and redemptive work in the first century and that he equips his church with the gospel, empowers her by the Spirit, and charges her with the Great Commission (Matt 28:19) to disciple all nations. Postmillennialism expects that eventually the vast majority of people living will be saved. Increasing gospel success will gradually produce a time in history prior to Christ's return in which faith, righteousness, peace, and prosperity will prevail in the affairs of men and of nations. After an extensive era of such conditions Jesus Christ will return visibly, bodily, and gloriously, to end history with the general resurrection and the final judgment after which the eternal order follows. Postmillennialism was a dominant theological belief among American Protestants who promoted reform movements in the 19th and 20th century such as abolitionism[71] and the Social Gospel.[72] Postmillennialism has become one of the key tenets of a movement known as Christian Reconstructionism. It has been criticized by 20th century religious conservatives as an attempt to immanentize the eschaton. AmillennialismAmillennialism, in Christian eschatology, involves the rejection of the belief that Jesus will have a literal, thousand-year-long, physical reign on the earth. This rejection contrasts with premillennial and some postmillennial interpretations of chapter 20 of the Book of Revelation. The amillennial view regards the "thousand years" mentioned in Revelation 20 as a symbolic number, not as a literal description; amillennialists hold that the millennium has already begun and is identical with the current church age. Amillennialism holds that while Christ's reign during the millennium is spiritual in nature, at the end of the church age, Christ will return in final judgment and establish a permanent reign in the new heaven and new earth. Many proponents dislike the name "amillennialism" because it emphasizes their differences with premillennialism rather than their beliefs about the millennium. "Amillennial" was actually coined in a pejorative way by those who hold premillennial views. Some proponents also prefer alternate terms such as nunc-millennialism (that is, now-millennialism) or realized millennialism, although these other names have achieved only limited acceptance and usage.[73] Death and the afterlifeJewish beliefs at the time of JesusThere were different schools of thought on the afterlife in Judea during the first century AD. The Sadducees, who recognized only the Torah (the first five books of the Old Testament) as authoritative, did not believe in an afterlife or any resurrection of the dead. The Pharisees, who accepted the Torah as well as additional scriptures, believed in the resurrection of the dead; it is known to have been a major point of contention between the two groups.[74] The Pharisees based their belief on Biblical passages such as Daniel 12:2[75] which says: "Multitudes who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake: some to everlasting life, others to shame and everlasting contempt." The intermediate stateSome traditions (notably, the Seventh-day Adventists) teach that the soul sleeps after death and will not awaken until the resurrection of the dead. Others believe the soul goes to an intermediate place where it will live consciously until the resurrection of the dead. By "soul", Seventh-day Adventist theologians mean the physical person (monism), and that no component of human nature survives death. Therefore, each human will be "recreated" at resurrection. One scripture frequently used to substantiate the assertion that souls experience mortality is found in the Book of Ezekiel: "Behold, all souls are Mine; The soul of the father as well as the soul of the son is Mine. The soul who sins shall die." (Ezekiel 18:4)[76] PurgatoryThis alludes to the Catholic belief in a spiritual state known as Purgatory during which souls not condemned to Hell but not completely pure go through a final process of purification before their full acceptance into Heaven. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) says:

Eastern Orthodoxy and Protestantism do not believe in Purgatory as such, but the Orthodox Church posits a period of continued sanctification after death. While the Eastern Orthodox Church rejects the term purgatory, it acknowledges an intermediate state after death and before final judgment, and offers prayer for the dead.[77] In general, Protestant churches reject the Catholic doctrine of purgatory (although some teach the existence of an intermediate state). The general Protestant view is that the Bible, from which Protestants exclude deuterocanonical books such as 2 Maccabees, contains no overt, explicit discussion of purgatory.[78] The Great TribulationThe end comes at an unexpected timeThere are many passages in the Bible, both Old and New Testaments, which speak of a time of terrible tribulation such as has never been known, a time of natural and human-made disasters on an awesome scale. Jesus said that at the time of his coming, "There will be great tribulation, such as has not been since the beginning of the world to this time, no, nor ever will be. And unless those days were shortened, no flesh would be saved; but for the elect's sake, those days will be shortened." [Matt 24:21–22] Furthermore, the Messiah's return and the tribulation that accompanies it will come at a time when people are not expecting it:

Paul echoes this theme, saying, "For when they say, 'Peace and safety!' then sudden destruction comes upon them."[79] The abomination of desolationThe abomination of desolation (or desolating sacrilege) is a term found in the Hebrew Bible, in the book of Daniel. The term is used by Jesus Christ in the Olivet Discourse, according to both the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Mark. In the Matthew account, Jesus is presented as quoting Daniel explicitly.

This verse in the Olivet Discourse also occurs in the Gospel of Luke.

Many biblical scholars[80] conclude that Matthew 24:15 and Mark 13:14 are prophecies after the event about the siege of Jerusalem in AD 70 by the Roman general Titus[81] (see Dating of the Gospel of Mark). Preterist Christian commentators believe that Jesus quoted this prophecy in Mark 13:14 as referring to an event in his "1st century disciples'" immediate future, specifically the pagan Roman forces during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD.[82][83] Futurist Christians consider the "Abomination of Desolation" prophecy of Daniel mentioned by Jesus in Matthew 24:15[84] and Mark 13:14[85] as referring to an event in the end time future, after the removal of the "one who now restrains", when a 7-year peace treaty will be signed between Israel and a world ruler called "the man of lawlessness", or the "Antichrist" affirmed by the writings of the Apostle Paul in 2 Thessalonians. Other scholars conclude that the Abomination of Desolation refers to the Crucifixion,[86] an attempt by the emperor Hadrian to erect a statue to Jupiter in the Jewish temple,[87] or an attempt by Caligula to have a statue depicting him as Zeus built in the temple.[88] The Prophecy of Seventy WeeksMany interpreters calculate the length of the tribulation at seven years. The key to this understanding is the "seventy weeks prophecy" in the book of Daniel. The Prophecy of Seventy Septets (or literally 'seventy times seven') appears in the angel Gabriel's reply to Daniel, beginning with verse 22 and ending with verse 27 in the ninth chapter of the Book of Daniel,[89] a work included in both the Jewish Tanakh and the Christian Bible; as well as the Septuagint.[90] The prophecy is part of both the Jewish account of history and Christian eschatology. The prophet has a vision of the angel Gabriel, who tells him, "Seventy weeks are determined for your people and for your holy city (i.e., Israel and Jerusalem)." [Dan 9:24] After making a comparison with events in the history of Israel, many scholars have concluded that each day in the seventy weeks represents a year. The first sixty-nine weeks are interpreted as covering the period until Christ's first coming, but the last week is thought to represent the years of the tribulation which will come at the end of this age, directly preceding the millennial age of peace:

This is an obscure prophecy, but in combination with other passages, it has been interpreted to mean that the "prince who is to come" will make a seven-year covenant with Israel that will allow the rebuilding of the temple and the reinstitution of sacrifices, but "in the middle of the week", he will break the agreement and set up an idol of himself in the temple and force people to worship it—the "abomination of desolation". Paul writes:

RaptureThe rapture is an eschatological term used by certain Christians, particularly within branches of North American evangelicalism, referring to an end time event when all Christian believers—living and dead—will rise into Heaven and join Christ.[91][92] Some adherents believe this event is predicted and described in Paul's First Epistle to the Thessalonians in the Bible,[93] where he uses the Greek harpazo (ἁρπάζω), meaning to snatch away or seize. Though it has been used differently in the past, the term is now often used by certain believers to distinguish this particular event from the Second Coming of Jesus Christ to Earth mentioned in Second Thessalonians, Gospel of Matthew, First Corinthians, and Revelation, usually viewing it as preceding the Second Coming and followed by a thousand-year millennial kingdom.[94] Adherents of this perspective are sometimes referred to as premillennialist dispensationalists, but amongst them there are differing viewpoints about the exact timing of the event. The term "rapture" is especially useful in discussing or disputing the exact timing or the scope of the event, particularly when asserting the "pre-tribulation" view that the rapture will occur before, not during, the Second Coming, with or without an extended Tribulation period.[95] The term is most frequently used among evangelical[96] and fundamentalist Christians in the United States.[97] Other, older uses of "rapture" were simply as a term for any mystical union with God or for eternal life in Heaven with God.[97] There are differing views among Christians regarding the timing of Christ's return, such as whether it will occur in one event or two, and the meaning of the aerial gathering described in 1 Thessalonians 4. Outside of American Evangelical Protestantism, almost all Christians do not subscribe to rapture-oriented theological views. Though the term "rapture" is derived from the text of the Latin Vulgate of 1 Thess. 4:17—"we will be caught up", (Latin: rapiemur), Catholics, as well as Eastern Orthodox, Anglicans, Lutherans and most Reformed Christians, do not generally use "rapture" as a specific theological term, nor do any of these bodies subscribe to the premillennialist dispensationalist theological views associated with its use, but do believe in the phenomenon—primarily in the sense of the elect gathering with Christ in Heaven after his Second Coming.[98][99][100] These denominations do not believe that a group of people is left behind on earth for an extended Tribulation period after the events of 1 Thessalonians 4:17.[101] Pre-tribulation rapture theology originated in the eighteenth century, with the Puritan preachers Increase Mather and Cotton Mather, and was popularized extensively in the 1830s by John Nelson Darby[102][103] and the Plymouth Brethren,[104] and further in the United States by the wide circulation of the Scofield Reference Bible in the early 20th century.[105] Some, including Grant Jeffrey, maintain that an earlier document called Ephraem or Pseudo-Ephraem already supported a pre-tribulation rapture.[106] The Second Coming Signs of Christ's returnThe Bible states:

Many, but not all, Christians believe:

Last Day CounterfeitsIn Matthew 24 Jesus states:

These false Christs will perform great signs and are no ordinary people "For they are spirits of demons, performing signs, which go out to the kings of the earth and of the whole world, to gather them to the battle of that great day of God Almighty." (Revelation 16:14) Satan's angels will also appear as godly clergymen, and Satan will appear as an angel of light.[112] "For such are false apostles, deceitful workers, transforming themselves into apostles of Christ. And no wonder! For Satan himself transforms himself into an angel of light. Therefore it is no great thing if his ministers also transform themselves into ministers of righteousness, whose end will be according to their works." (2 Corinthians 11:13–15) The Marriage of the LambAfter Jesus meets his followers "in the air", the marriage of the Lamb takes place: "Let us be glad and rejoice and give him glory, for the marriage of the Lamb has come, and his wife has made herself ready. And to her was granted that she should be arrayed in fine linen, clean and bright, for the fine linen is the righteous acts of the saints" [Rev 19:7–8]. Christ is represented throughout Revelation as "the Lamb", symbolizing the giving of his life as an atoning sacrifice for the people of the world, just as lambs were sacrificed on the altar for the sins of Israel. His "wife" appears to represent the people of God, for she is dressed in the "righteous acts of the saints". As the marriage takes place, there is a great celebration in heaven which involves a "great multitude" [Rev 19:6]. Resurrection of the dead

Doctrine of the resurrection predates ChristianityThe word resurrection comes from the Latin resurrectus, which is the past participle of resurgere, meaning to rise again. Although the doctrine of the resurrection comes to the forefront in the New Testament, it predates the Christian era. There is an apparent reference to the resurrection in the book of Job, where Job says, "I know that my redeemer lives, and that he will stand at the latter day upon the earth. And though... worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh I will see God" [Job 19:25–27]. Again, the prophet Daniel writes, "Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, some to shame and everlasting contempt" [Dan 12:2]. Isaiah says: "Your dead will live. Together with my dead body, they will arise. Awake and sing, you who dwell in dust, for your dew is like the dew of herbs, and the earth will cast out the dead" [Isa. 26:19]. This belief was still common among the Jews in New Testament times, as exemplified by the passage which relates the raising of Lazarus from the dead. When Jesus told Lazarus' sister, Martha, that Lazarus would rise again, she replied, "I know that he will rise again in the resurrection at the last day" [Jn 11:24]. Also, one of the two main branches of the Jewish religious establishment, the Pharisees, believed in and taught the future resurrection of the body [cf Acts 23:1–8]. Two resurrectionsAn interpretation of the New Testament is the understanding that there will be two resurrections. Revelation says: "Blessed and holy is he who has part in the first resurrection. Over such, the second death has no power, but they will be priests of God and of Christ, and will reign with him a thousand years" [Rev 20:6]. The rest of the dead "did not live again until the thousand years were finished" [Rev 20:5]. Despite this, there are various interpretations:

The resurrection bodyThe Gospel authors wrote that our resurrection bodies will be different from those we have now. Jesus said, "In the resurrection, they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like the angels of God in heaven" [Mt 22:30]. Paul adds, "So also is the resurrection of the dead: the body ... is sown a natural body; it is raised a spiritual body" [1 Co. 15:42–44]. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church the body after resurrection is changed into a spiritual, imperishable body:

Both the righteous and the wicked will rise with immortal bodies. However, only the righteous will rise with four endowments: impassibility (incorruptibility), subtility (spirituality), agility (power), and clarity (glory).[115] In some ancient traditions, it was held that the person would be resurrected at the same spot where they died and were buried (just as in the case of Jesus' resurrection). For example, in the early medieval biography of St Columba written by Adomnan of Iona, Columba at one point prophesies to a penitent at the monastery on Iona that his resurrection would be in Ireland and not in Iona, and this penitent later died at a monastery in Ireland and was buried there.[116] Other viewsAlthough Martin Luther personally believed and taught resurrection of the dead in combination with soul sleep, this is not a mainstream teaching of Lutheranism and most Lutherans traditionally believe in resurrection of the body in combination with the immortal soul.[117] Several churches, such as the Anabaptists and Socinians of the Reformation, then Seventh-day Adventist Church, Christadelphians, Jehovah's Witnesses, and theologians of different traditions reject the idea of the immortality of a non-physical soul as a vestige of Neoplatonism, and other pagan traditions. In this school of thought, the dead remain dead (and do not immediately progress to a Heaven, Hell, or Purgatory) until a physical resurrection of some or all of the dead occurs at the end of time. Some groups, Christadelphians in particular, consider that it is not a universal resurrection, and that at this time of resurrection that the Last Judgment will take place.[118] Armageddon Megiddo is mentioned twelve times in the Old Testament, ten times in reference to the ancient city of Megiddo in the Jezreel Valley, and twice with reference to "the plain of Megiddo", most probably simply meaning "the plain next to the city".[119] None of these Old Testament passages describes the city of Megiddo as being associated with any particular prophetic beliefs. The one New Testament reference to the city of Armageddon found in Revelation 16:16 also makes no specific mention of any armies being predicted to one day gather in this city, but instead seems to predict only that "they (will gather) the kings together to .... Armageddon".[120] The text does however seem to imply, based on the text from the earlier passage of Revelation 16:14, that the purpose of this gathering of kings in the "place called Armageddon" is "for the war of the great day of God, the Almighty". Because of the seemingly highly symbolic and even cryptic language of this one New Testament passage, some Christian scholars conclude that Mount Armageddon must be an idealized location.[121] R. J. Rushdoony says, "There are no mountains of Megiddo, only the Plains of Megiddo. This is a deliberate destruction of the vision of any literal reference to the place."[122] Other scholars, including C. C. Torrey, Kline and Jordan argue that the word is derived from the Hebrew moed (מועד), meaning "assembly". Thus, "Armageddon" would mean "Mountain of Assembly," which Jordan says is "a reference to the assembly at Mount Sinai, and to its replacement, Mount Zion."[121] The traditional viewpoint interprets this biblical prophecy to be symbolic of the progression of the world toward the "great day of God, the Almighty" in which the great looming mountain of God's just and holy wrath is poured out against unrepentant sinners, led by Satan, in a literal end-of-the-world final confrontation. Armageddon is the symbolic name given to this event based on scripture references regarding divine obliteration of God's enemies. The hermeneutical method supports this position by referencing Judges 4 and 5 where God miraculously destroys the enemy of His elect, Israel, at Megiddo, also called the Valley of Josaphat.[citation needed] Christian scholar William Hendriksen says:

The MillenniumMillennialism (from millennium, Latin for "a thousand years"), or chiliasm (from the Greek equivalent), is the belief that a Messianic Age will occur on Earth prior to the final judgment and future eternal state of the "World to Come". Christian millennialism developed out of a Christian interpretation of Jewish apocalypticism. Christian millennialist thinking is primarily based upon the Book of Revelation, specifically 20:1–4,[124] which describes the vision of an angel who descended from heaven with a large chain and a key to a bottomless pit, and captured Satan, imprisoning him for a thousand years:

The Book of Revelation then describes a series of judges who are seated on thrones, as well as his vision of the souls of those who were beheaded for their testimony in favor of Jesus and their rejection of the mark of the beast:

Thus, Revelation characterizes a millennium where Christ and the Father will rule over a theocracy of the righteous. While there are an abundance of biblical references to such a kingdom of God throughout the Old and New Testaments, this is the only reference in the Bible to such a period lasting one thousand years. The literal belief in a thousand-year reign of Christ is a later development in Christianity, as it does not seem to have been present in first century texts.[125] The End of the World and the Last JudgmentSatan releasedAccording to the Bible, the Millennial age of peace all but closes the history of planet Earth. However, the story is not yet finished: "When the thousand years have expired, Satan will be released from his prison and will go out to deceive the nations which are in the four corners of the earth, Gog and Magog, to gather them together to battle, whose number is as the sand of the sea." [Rev 20:7–8] There is continuing discussion over the identity of Gog and Magog. In the context of the passage, they seem to equate to something like "east and west". There is a passage in Ezekiel, however, where God says to the prophet, "Set your face against Gog, of the land of Magog, the prince of Rosh, Meshech, and Tubal, and prophesy against him." [Ezek 38:2] Gog, in this instance, is the name of a person of the land of Magog, who is ruler ("prince") over the regions of Rosh, Meshech, and Tubal. Ezekiel says of him: "You will ascend, coming like a storm, covering the land like a cloud, you and all your troops and many peoples with you..." [Ezek 38:2] Despite this huge show of force, the battle will be short-lived, for Ezekiel, Daniel, and Revelation all say that this last desperate attempt to destroy the people and the city of God will end in disaster: "I will bring him to judgment with pestilence and bloodshed. I will rain down on him and on his troops, and on the many peoples who are with him: flooding rain, great hailstones, fire and brimstone." [Ezek 38:22] Revelation concurs: "Fire came down from God out of heaven and devoured them." [Rev 20:9] It may be that the images of fire raining down are an ancient vision of modern weapons, others would say a supernatural intervention by God, yet others that they refer to events in history, and some would say they are symbolic of larger ideas and should not be interpreted literally. The Last JudgmentFollowing the defeat of Gog, the last judgment begins: "The devil, who deceived them, was cast into the lake of fire and brimstone where the beast and the false prophet are, and they will be tormented day and night forever and ever" [Rev 20:10]. Satan will join the Antichrist and the False Prophet, who were condemned to the lake of fire at the beginning of the Millennium. Following Satan's consignment to the lake of fire, his followers come up for judgment. This is the "second resurrection", and all those who were not a part of the first resurrection at the coming of Christ now rise up for judgment:

John had earlier written, "Blessed and holy is he who has part in the first resurrection. Over such the second death has no power" [Rev 20:6]. Those who are included in the Resurrection and the Rapture are excluded from the final judgment, and are not subject to the second death. Due to the description of the seat upon which the Lord sits, this final judgment is often referred to as the Great White Throne Judgment. A decisive factor in the Last Judgement will be the question, if the corporal works of mercy were practiced or not during lifetime. They rate as important acts of charity. Therefore, and according to the biblical sources (Matt 5:31–46), the conjunction of the Last Judgement and the works of mercy is very frequent in the pictorial tradition of Christian art.[126] New Heaven and New Earth

New JerusalemThe focus turns to one city in particular, the New Jerusalem. Once again, we see the imagery of the marriage: "I, John, saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband" [Rev 21:2]. In the New Jerusalem, God "will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God..." [Rev 21:3]. As a result, there is "no temple in it, for the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are its temple." Nor is there a need for the sun to give its light, "for the glory of God illuminated it, and the Lamb is its light" [Rev 21:22–23]. The city will also be a place of great peace and joy, for "God will wipe away every tear from their eyes. There will be no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying; and there will be no more pain, for the former things have passed away" [Rev 21:4]. DescriptionThe city itself has a large wall with twelve gates in it which are never shut, and which have the names of the twelve tribes of Israel written on them. Each of the gates is made of a single pearl, and there is an angel standing in each one. The wall also has twelve foundations which are adorned with precious stones, and upon the foundations are written the names of the twelve apostles. The gates and foundations are often interpreted[by whom?] as symbolizing the people of God before and after Christ. The city and its streets are pure gold, but not like the gold we know, for this gold is described as being like clear glass. The city is square in shape, and is twelve thousand furlongs long and wide (fifteen hundred miles). If these are comparable to earthly measurements, the city will cover an area about half the size of the contiguous United States. The height is the same as the length and breadth, and although this has led most people to conclude that it is shaped like a cube, it could also be a pyramid. The Tree of Life The city has a river which proceeds "out of the throne of God and of the Lamb".[130] Next to the river is the tree of life, which bears twelve fruits and yields its fruit every month. The last time we saw the tree of life was in the Garden of Eden [Gen 2:9]. God drove Adam and Eve out from the garden, guarding it with cherubim and a flaming sword, because it gave eternal life to those who ate of it[131] In the New Jerusalem, the tree of life reappears, and everyone in the city has access to it. Genesis says that the earth was cursed because of Adam's sin,[132] but the author of John writes that in the New Jerusalem, "there will be no more curse".[133] The Evangelical Dictionary of Theology (Baker, 1984) says:

See also

References

|