|

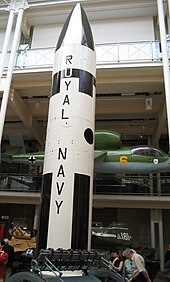

Chevaline Chevaline (/ˈʃɛvəliːn/) was a system to improve the penetrability of the warheads used by the British Polaris nuclear weapons system. Devised as an answer to the improved Soviet anti-ballistic missile defences around Moscow, the system increased the probability that at least one warhead would penetrate Moscow's anti-ballistic missile (ABM) defences, something which the Royal Navy's earlier UGM-27 Polaris re-entry vehicles (RVs) were thought to be unlikely to do.  Chevaline used a variety of penetration aids and decoys to offer so many indistinguishable targets that an opposing ABM system would be overwhelmed attempting to deal with them all, ensuring that enough warheads would get through an ABM defence to be a reasonable deterrent to a first strike. The project was highly secret, and survived in secrecy through four different governments before being revealed in 1980. The system was in service from 1982 to 1996, when the Polaris A3T missiles it was fitted to were replaced with the Trident D5. Military and political requirementsThe origins of the Chevaline requirement grew from the conclusion of several British governments that in the event of a Soviet nuclear attack on the UK alone, as had been threatened in late 1950s by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and Prime Minister Nikolai Bulganin[3] it was unrealistic to expect that the US would retaliate against the Soviet Union and risk an attack on major American cities. That conclusion by successive British governments was the basis of their justification given to the British people for an independent nuclear retaliatory capability. For some time this deterrent force had been based on the Royal Air Force's V bomber force. This looked increasingly vulnerable in the face of ever-increasing Soviet Air Defence Forces, and various reports by the RAF suggested their bombers would be incapable of successfully delivering free-fall ("gravity") bombs by 1960. This had been considered from the early 1950s and the planned solution was a move to the Blue Streak medium range ballistic missile, but this suffered extensive delays for a variety of reasons. As it became clear Blue Streak would not be available by 1960, interim solutions were considered. Among many possibilities, the RAF eventually selected the Blue Steel standoff missile to allow its bombers to fire their weapons while still (hopefully) outside the range of the defensive fighters. This system provided marginal capability and a number of projected developments were considered as Blue Steel II, which increased both its range to improve the survivability of the bomber and speed to improve the survivability of the missile. A better solution came along in the form of the US's AGM-48 Skybolt missile. The US bomber force was facing the same sorts of problems as the British V bombers, and were attempting to solve it in a similar fashion, with a long-range standoff missile. In this case the missile had a projected range of just under 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi). The distance from London to Moscow is about 2,500 kilometres (1,600 mi), so Skybolt would allow the V-bomber force to attack Russia from sites not far off the British coast, with complete impunity. Skybolt seemed like such a good solution that work on both Blue Steel II and Blue Streak were cancelled. Skybolt development was cancelled in early 1962 and led to a major political row. Finally a compromise was reached later that year; the Nassau Agreement had the Royal Navy taking over the deterrent role with newly acquired Polaris missiles. This arrangement was formally outlined in the Polaris Sales Agreement. One key part of the agreement was that the UK would develop their own warheads for the missiles, as the UK military and political establishments were rather worried about losing their own nuclear production and design capability. Having already put some effort into the Skybolt warhead, it was decided to adapt this design, based on the thermonuclear secondary of the US W59, matched to a primary trigger based on a wholly UK design developed from the Cleo device tested at the Pampas instead of the W58 used on US Navy missiles. The ABM problem Throughout this period both the US and USSR were working on anti-ballistic missile systems. Developing an ABM system was largely an engineering issue, requiring radars with high resolution and targeting computers that could adjust trajectories fast enough given an approach speed in thousands of miles an hour. Given that these items would be expensive, the ABM interceptor itself was likely to cost about the same as an ICBM (or less), so any increase in the enemy's stockpile could be countered for an additional expenditure of about the same amount. This was a game the US was clearly willing to play, although it would seem the USSR was considerably less capable of doing so given the size of the two countries' respective economies. The Soviets were confirmed as working on an ABM system in 1961 when they made their first successful exo-atmospheric interception of an ICBM. An American response was to develop "Antelope", a system designed to overwhelm an ABM defence with decoys, or penaids (penetration aids). In the end the US abandoned Antelope because they could achieve the same ends simply by throwing additional warheads, which was becoming increasingly inexpensive with the introduction of MIRVs. With MIRV, a single missile could launch multiple warheads that separated in space, forcing the defender to use multiple ABMs to attack them. A single new ballistic missile would demand multiple ABMs to counter it, this cost-exchange ratio ultimately convincing the US that ABMs were infeasible. This development left the British in a particularly bad position. Although the Polaris was fairly immune to direct attack in the submerged ballistic missile submarines, this meant little if the warheads could not make it through the Soviet defences – especially if the Soviets were convinced of this. Although Polaris did have multiple warheads, they were not MIRV - all three were released on the same trajectory and remained fairly close together during atmospheric entry. This meant that all three could be attacked by a single ABM with a large warhead. A single Resolution-class submarine with 16 missiles would throw a total of 48 warheads, making it conceivable that many of them might be destroyed by even a small number of ABMs. This meant the fleet could no longer guarantee the success of the deterrent's objective – to threaten Soviet state power. Something had to be done in order to maintain the relevance of the UK's nuclear deterrent. Although developments in the ABM field had been watched throughout the 1960s, exactly what to do about the problem apparently remained a fairly low priority. In 1967 the US offered a newer version of the Polaris, the A3T design, which featured a "hardened" missile airframe intended to better protect it against ABMs. As the UK had not yet received their missiles, they agreed to use the A3T version as it required relatively few other changes.[citation needed] KH.793In 1970 serious efforts to explore the ABM problem started. By this point the US and USSR had agreed in the ABM Treaty to deploy up to 100 ABMs at only two sites. MIRVs had so seriously upset the balance between ABM and ICBM that both parties agreed to limit ABM deployment largely as a way of avoiding a massive buildup of new ICBMs. The only good news for the UK in this development was that it clearly defined the problem they were facing; their attacks had to be able to credibly defeat a 100-interceptor ABM defence around Moscow. Thus started project KH.793, a one-year project to identify potential solutions. One option would be to build additional Polaris platforms and keep more of them at sea. Two Resolutions would throw 96 warheads and almost guarantee penetration, while three would make it a certainty. This would require a fleet of at least five submarines to keep two on station at all times, as well as larger crew complements, training and logistics support, and appeared to be the most expensive option. Several "low cost" options were also explored. Among these were "Topsy", the A3T missile the UK had already agreed to use. Another option was Antelope, which used hardened warheads along with penaids, although it reduced the payload to two warheads in order to save weight for the penaids. They also explored a "superhardened" version known as Super Antelope, a further improvement on the warhead that also used a manoeuvrable warhead "bus" to deploy the penaids further apart in space. The Royal Navy preferred to upgrade to the Poseidon missile, increasing the number of warheads from three per missile to between ten and thirteen of a newer and lighter design. In this case a single Resolution could launch up to 208 warheads, guaranteeing that some would get through. This option also had the advantage of maintaining commonality with the US Navy, as well as offering greater range, and thus increasing the safety of the launch submarines. The US also favoured the Poseidon, although for more technical reasons. They felt that while the decoy approach was useful against near-term ABMs deployed by the USSR, that it was considerably less useful against "point defence" type interceptors. This is because the decoys are so much lighter than warheads; when they started to hit the upper atmosphere the decoys would slow more than the warheads and thus "declutter", allowing the warheads to be attacked. This would require a much faster-reacting radar and computer system than an ABM using a long-range interceptor, one that could safely wait until only a few moments before detonation, but this was by no means impossible and was part of the US's own ABM systems. As the UK had decided to produce its own warheads and bus, this option would require considerable development effort in order to produce a new MIRV bus of their own. Although in theory the UK might be able to use the US-designed bus, these options were being explored in the midst of the ABM Treaty, and it was not clear whether the treaty might forbid this technology being transferred. Some related options were explored, including "Option M" which used a simple "de-MIRVed" bus, "Hybrid" (or "Stag") which put the newer Poseidon warheads on the existing Polaris A3T missiles, and "Mini Poseidon", a similar adaptation with a smaller six-Poseidon-warhead payload on the A3T. In the end the higher levels of the British political system decided against the urgings of their own Chiefs of Staff and went with the penaid approach on the existing A3T missile. This decision was made official late in 1973 by the Edward Heath administration, which changed the name from Super Antelope to Chevaline. The name 'Chevaline' was the result of a telephone call to London Zoo from an official at the Ministry of Defence. Prompted by a request for a name-change from his boss, the Secretary of State for Defence, Lord Carrington, the official asked the zoo to 'imagine an animal like a large antelope' and inquired whether there was such a beast. The zoo told him there was a South African creature called a Chevaline, and the official 'thought that sounded rather good'.[4] (The creature to which the zoo was probably referring was the Roan Antelope, Hippotragus equinus which is known in French as 'Antilope chevaline'.) Initially it was planned to make the project public, but a change of government in the 1974 elections ended these plans. A new review again concluded that the project should continue, even though the naval staff continued to be opposed. Full development started in January 1975.  DevelopmentThe project was carried out in extreme secrecy by a team consisting of the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) at Aldermaston, the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough, and Hunting Engineering at Ampthill, Sperry Gyroscope at Bracknell, Lockheed Aerospace in the United States, and others, both in the US and the UK. The system was tested at the US Eastern Test Range, Cape Canaveral, and the warheads were tested with two full scale underground nuclear tests (Fallon in 1974 and Banon in 1976) at the Nevada Test Site. There were also numerous weapon effects tests to prove the RV/warhead resistance to the radiation-effects of the Galosh warhead; and there were numerous missile tests at the Woomera Missile Range, Australia, to develop various aspects of the RVs, the PAC and decoys. Recent declassifications of official files show that more than half the total project costs were spent in the United States, with industry and government agencies. Range of the "Improved" Chevaline system was 22% less than the "Unimproved" Polaris A3T, reduced from 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km) to 1,950 nmi (3,610 km). This was the source of continuing pressure on the development team from the Naval Staff, who had set the minimum requirement at 2,000 nmi (3,700 km), and who were deeply concerned at intelligence reports of improving Soviet anti-submarine warfare capabilities. Reduced missile range had the effect of reducing the sea-room in which the British submarines could hide. With Chevaline, the patrol area was limited to the north of and just around the GIUK gap, whereas previously they could operate within an area to the south of the Gap as well. This was a serious problem, because much of NATOs anti-submarine strategy was based on closing the Gap, with the implicit assumption that areas north of it would be fairly easy for Soviet submarines to operate within. If the Polaris fleet was forced to operate to the north of the line, or even within a limited distance of it, they would be lacking the protection of the bulk of the NATO forces, and potentially in the midst of a high concentration of enemy hunter-killer subs. Efforts were made to reduce warhead weight by substituting a new, smaller, high-yielding thermonuclear primary tested at Fondutta and Quargel, and although these tests were deemed successful, the delays involved in preparing them for Chevaline were thought to risk further unacceptable delays to the in-service date planned, and they were not used. This thermonuclear primary was by then being referred to in official documents as a "trigger device" and some suspect that this new description was a sleight-of-hand to circumvent the pledge given by Prime Minister Wilson of "no new generation of nuclear weapons". The thermonuclear (or fusion) secondary for Chevaline and known to AWRE by the codename Reggie, is known from these declassified documents to be recycled from the "Unimproved" Polaris A3T warhead. Further political developmentsThe Chevaline project was kept secret by successive UK governments, both Labour and Conservative. This secrecy was maintained under Harold Wilson, Edward Heath, Harold Wilson's second term and James Callaghan. The project was finally revealed by Margaret Thatcher's then defence minister Francis Pym.[6] The reasons for revelation were both political and practical. The cost over-runs of the project were now so enormous (approximately £1 billion by 1979) that the secret inner-Cabinet spending approvals could not continue. The key decision to proceed had been taken in 1975, four years previously, and cancellation would be unlikely to save money at that point. Even if it were to be cancelled, a replacement would have to be ordered in any case. Shortly afterwards the Thatcher government decided that the successor system should be the Trident system and ordered the C4 variant. The Naval Staff angst that had been a feature of the Chevaline project surfaced here too. For several reasons the Navy had not wanted Chevaline and had actively lobbied against it. Their preference for Poseidon was in large part based on commonality of equipment. Polaris was being phased out of use by the US Navy and supplies of spares and repair facilities were becoming unavailable. To keep the Polaris missile in use in the UK meant that some production lines had to be re-opened at great cost to supply a very small force. A missile common to both navies was desirable, and the Naval Staff strongly argued against Chevaline. At one point, several of their counterparts in the US Navy had encouraged them to seek congressional approval for such a proposal through a formal request from the Ministry of Defence.[7] Although the papers will not be declassified for some time yet, it seems likely that the Naval Staff made the same case with Trident with some success when their influence was at its height after the Falklands War. The US later decided to move primary development from the C4 to the larger Trident D5, a much more capable missile, but one that would not fit into the latest Ohio-class submarines, let alone the older Benjamin Franklin class. Their solution to this problem was to change the design of the Ohio class to allow for the larger D5. Thatcher, who was fully committed to Trident, decided to follow the same route and authorized the design of the Vanguard-class to carry them. They agreed to a deal whereby the US and British combined missile stock is serviced at a single location at the US Navy facility at Kings Bay, Georgia, and from there missiles are issued to both US and British submarines. Only the warheads (added later to British missiles) are different. Finally, recently published recollections from senior members of the development team are explicit in stating that Chevaline was not the best, or with hindsight, the cheapest choice the British could have made from the many options available. But the choices were never simple but overlaid with what was politically possible, what was in the best interests of UK industry and its scientific base. In the end, the alternatives were "between Chevaline or nothing at all; a decision which could easily have meant withdrawal of the UK from the military political nuclear scene" and that option was unthinkable to the military staffs and government alike.[6] Description The response to the threat of interception by ABM-1 Galosh missiles was to deploy an upgraded or Improved Front End (IFE) to Polaris A3T using the Antelope/Super Antelope/Chevaline technology. The Chevaline solution was to decrease the number of warheads carried by the Polaris system from three to two, using the space and weight to carry numerous decoys, and increase the likelihood of warhead survival by substituting a new super-hardened thermonuclear primary for the warhead contained in a new super-hardened RV. The IFE was built in two primary parts. One warhead was mounted directly to the front of the second stage, as had been the case for all three warheads in the original Polaris. The second part was the "penetration aid carrier", or PAC, which carried the second warhead along with the various penetration aids. The PAC dispensed one RV but the principal purpose of its manoeuvring capability was to dispense the 27 decoys into a 'threat tube' surrounding the RVs, which also had a 'disguise' to match their radar appearance to the decoys. The system was not a MIRVing system because the target of both warheads was one location, about which the two warheads were spread, as in the earlier MRV system of Polaris A3T. In the case of an attack on the USSR, even a single Resolution could have ensured the destruction of a significant portion of the Soviet command and control structure. Given all sixteen missiles launching successfully, an ABM system would be presented with 551 credible-looking targets to deal with. Given that the ABM treaty limited the USSR to 100 ABM interceptors, a "hit" was virtually guaranteed.[citation needed] The 'unimproved' British Polaris A3T carried three 200 kt warheads[8] designated ET.317 in U.S. Mk-2 RVs, composed of a primary known as Jennie and a thermonuclear secondary known as Reggie.[9] The integrated upgraded Polaris system was known as A3TK and carried two warheads in upgraded British-designed RVs. These warheads used the new Harriet[9] primary with Reggie re-used from the ET.317 warhead,[10] and their nuclear yield increased to 225 kt.[11] This system was in service from 1982 to 1996, when it was replaced by Trident D5. Re-entry Body (ReB)ConstructionWhilst the fully assembled Chevaline ReB and a new warhead was of identical external shape, and balance to US Polaris RVs to minimise development costs and avoid the need for full-scale flight testing, the Chevaline ReB was unusual in using a new material known as 3-Dimensional Quartz Phenolic (3DQP),[12] which was developed in the UK and subsequently used on US warheads. 3DQP is a phenolic-based material composed of a quartz cloth material woven into a seamless sock shape cloth impregnated with a phenolic resin and hot-pressed. The quartz material 'hardens' the ReB protecting the nuclear warhead against high-energy neutrons emitted by exo-atmospheric Anti-ballistic missile (ABM) bursts before re-entry.[13] When cured, 3DQP can be machined in the same way as metals and is tough and fire-resistant. ManufactureA licence to manufacture 3DQP in the US was acquired and production was undertaken by AVCO, one of the two suppliers of US RVs, the other being General Electric. The first production examples of the Chevaline ReB were manufactured by AVCO, now part of Textron[14] before production began in the UK at the Royal Ordnance Factory at Burghfield, now incorporated into the Atomic Weapons Establishment, Aldermaston, using quartz thread material obtained from France.[15] Components for the Chevaline system were manufactured at the Royal Ordnance Factory (Cardiff), which in turn was renamed (along with ROF Burghfield) AWE Cardiff in 1987. The Beryllium facility (Project B) at Cardiff, as well as the other workshops at the site, manufactured high precision components relating to the PAC and the decoys for Chevaline, as well as in later years pre-production components and gauges for Trident, before being decommissioned and closed in the mid ‘90s when full production moved to Burghfield. Later, the supply of test samples of 3DQP to France without UK permission caused friction between the British Government and AVCO, and action in the US courts by the British government.[16] See alsoFootnotes

ReferencesWikimedia Commons has media related to Chevaline.

|