|

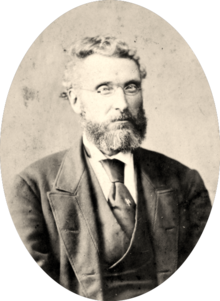

Charles Kickham

Charles Joseph Kickham (9 May 1828 – 22 August 1882) was an Irish revolutionary, novelist, poet, journalist and one of the most prominent members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Early lifeCharles Kickham was born at Mullinahone, County Tipperary, on 9 May 1828.[1] His father John Kickham was the proprietor of the principal drapery in the locality and was held in high esteem for his patriotic spirit.[2] His mother, Anne O'Mahony, was related to the Fenian leader John O'Mahony.[3] Charles Kickham grew up largely deaf and almost blind, the result of an explosion with a powder flask when he was 13. He was educated locally, where it was intended he study for the medical profession.[4] During his boyhood the Repeal agitation was at its height, and he soon became versed in its arguments and was inspired by its principles. He often heard the issues discussed in his father's shop and at home amongst all his friends and acquaintances.[2] The NationFrom a young age he was imbued with these patriotic ideals.[5][6] He became acquainted with the teaching of the Young Irelanders through their newspaper The Nation from its foundation in October 1842. Kickham's father used to read the paper aloud every week for the family. This reading would include the speeches in Reconciliation Hall (home of the Repeal Association) and reports on Repeal meetings in the provinces. Also of interest were the lead articles and literary pages, including, the "Poet’s Corner."[4] Like all the young people of the time, and a great many of the old ones, according to Seán Ua Ceallaigh, his sympathies went with the Young Irelanders on their secession from the Repeal Association. Kickham contributed when he was 22 years old, The Harvest Moon sung to the air of "The Young May Moon", to The Nation on 17 August 1850. Other verses were to follow, but the finest of Kickham's poems according to A. M. O'Sullivan, appeared in other journals. Rory of the Hill, The Irish Peasant Girl, and Home Longings better known as Slievenamon were published in the Celt. The First Felon (John Mitchel) appeared in the Irishman. Patrick Sheehan, the story of an old soldier, was published in the Kilkenny Journal, and became very popular as an anti-recruiting song, according to O'Sullivan.[4] Kickham began to write for a number of papers, including The Nation, but also the Celt, the Irishman, the Shamrock, and would become one of the leader writers of the Irish People, the Fenian organ, in which many of his poems appeared. His writings were signed using his initials, his full name, or the pseudonyms, "Slievenamon" and "Momonia."[4] 1848 RebellionKickham was the leading member of the Confederation Club in Mullinahone, which he was instrumental in founding,[2] and when the revolutionary spirit began to grip the people in 1848 turned out with a freshly made pike to join William Smith O'Brien and John Blake Dillon when they arrived in Mullinahone in July 1848.[4] On hearing of the progress of O’Brien through the country, Kickham had set to work manufacturing pikes, and was in the forge when news reached him that the leaders were looking for him. It was here that Kickham would meet James Stephens for the first time.[7] At O’Brien's request, he rang the chapel bell to summon the people and before midnight a Brigade had answered the summons.[4] Kickham would later write a detailed account about this period which brought his connection with the attempted Rising of 1848 to a close.[8] Irish Republican BrotherhoodAfter the failed 1848 uprising at Ballingarry he had to hide for some time, as a result of the part he had played in rousing the people of his native village to action.[2][5] When the excitement had subsided, he returned to his father's house and resumed his interests in the sports of fishing and fowling, and spent much of his time in literary pursuits, for which he had great natural capacity and all the more inclined as a result of the accident.[2] Some of the authors in which he was well versed were Tennyson and Dickens and he greatly admired George Eliot, and after Shakespeare, was Burns.[9] In the autumn of 1857, a messenger, Owen Considine arrived from New York with a message for James Stephens from members[10] of the Emmet Monument Association, calling on him to get up an organization in Ireland.[11] On 23 December, Stephens dispatched Joseph Denieffe to America with his reply and outlined his conditions and his requirements from the organisation in America.[12] Denieffe returned on 17 March (St. Patrick's Day) 1858 with the acceptance of Stephens' terms and £80. That evening the Irish Republican Brotherhood commenced.[13][14] Those present in Langan's, lathe-maker and timber merchant, 16 Lombard Street, for that first meeting were Stephens, Kickham, Thomas Clarke Luby, Peter Langan, Denieffe[15] and Garrett O'Shaughnessy.[16][17] Later it would include members of the Phoenix National and Literary Society, which was formed in 1856 by Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa in Skibbereen.[18] Irish People In mid-1863, Stephens informed his colleagues he wished to start a newspaper, with financial aid from O’Mahony and the Fenian Brotherhood in America. The offices were established at 12 Parliament Street, almost at the gates of Dublin Castle.[19] The first number of The Irish People appeared on 28 November 1863.[20] The staff of the paper along with Kickham were Luby and Denis Dowling Mulcahy as the editorial staff. O’Donovan Rossa and James O’Connor had charge of the business office, with John Haltigan being the printer. John O'Leary was brought from London to take charge in the role of Editor.[21] Shortly after the establishment of the paper, Stephens departed on an America tour, and to attend to organizational matters.[22] Before leaving, he entrusted to Luby a document containing secret resolutions on the Committee of Organization or Executive of the IRB. Though Luby intimated its existence to O’Leary, he did not inform Kickham as there seemed no necessity. This document would later form the basis of the prosecution against the staff of the Irish People. The document read:[23]

Kickham's first contribution to The Irish People appeared in the third number titled, “Leaves from a Journal,” based on a journal kept by Kickham on his way to America in 1863. This article left no doubt as to his literary capacity according to O’Leary. The third edition also saw the last article by Stephens titled "Felon-setting", a much-used phrase now to the Irish political vocabulary.[24] It would fall to Kickham, as a good Catholic, to tackle the priests,[25] though not exclusively with articles such as "Two Sets of Principles", a rebuff to the doctrines laid down by Lord Carlisle, and "A Retrospect", dealing with the tenant-right movement chiefly but also the events of the recent past and their bearing on the present.[26] Kickham articulated the attitude held by the IRB in relation to priests, or more particularly in politics:[27]

On 15 July 1865, American-made plans for a rising in Ireland were discovered when the emissary lost them at Kingstown railway station. They found their way to Dublin Castle and to Superintendent Daniel Ryan head of G Division. Ryan had an informer within the offices of The Irish People named Pierce Nagle. He supplied Ryan with an "action this year" message on its way to the IRB unit in Tipperary. With this information, Ryan raided the offices of The Irish People on Thursday 15 September, followed by the arrests of O’Leary, Luby, and O’Donovan Rossa. Kickham was caught after a month on the run.[28] Stephens would also be caught but with the support of Fenian prison warders, John J. Breslin[29] and Daniel Byrne was less than a fortnight in Richmond Bridewell when he vanished and escaped to France.[30] The last number of the paper is dated 16 September 1865.[31] Trial and SentenceOn 11 November 1865, Kickham was convicted of treason and sentenced to fourteen years' penal servitude.[4][32] The prisoners' refusal to disown their opposition to British rule in any way, even when facing charges of life-imprisonment, earned them the nickname of 'the bold Fenian men'.[33] In the course of his speech from the Dock Kickham was to say:[34][35]

Quoting then from Thomas Davis Kickham continued:

The judge William Keogh, before passing sentence, asked him if he had any further remarks to make in reference to his case. Mr. Kickham briefly replied: "I believe, my lords, I have said enough already. I will only add that I am convicted for doing nothing but my duty. I have endeavoured to serve Ireland, and now I am prepared to suffer for Ireland." Then the judge with many expressions of sympathy for the prisoner, and many compliments in reference to his intellectual attainments, sentenced him to be kept in penal servitude for fourteen years.[34] Kickham spent time from 1866 until his release in the Invalid Prison at Woking.[36] Kickham was given a free pardon from Queen Victoria on 24th February 1869[37] because of ill-health, and upon his release he was made Chairman of the Supreme Council of the I.R.B. and, according to Devoy, 'the unchallenged leader' of the reorganized movement.[38] According to Desmond Ryan, Kickham was an effective orator and chairman of meetings despite his physical handicaps. He wore an ear trumpet, and could only read when he held books or papers within a few inches of his eyes. Kickham, for many years, carried on conversations by means of the deaf and dumb alphabet.[38] KnocknagowKnocknagow, published in 1873, is a novel about the life of the Irish peasantry and is concerned with the workings of the Irish land system. The novel portrays landlords as apathetic to the needs of their tenants and their land agents as greedy and unscrupulous, leading to rural depopulation, emigration and poverty. The lives of the characters illustrate the iniquities of the land system but Kickham also provides a positive portrait of the virtues of Irish life.[39] The novel centres around the land owner Sir Garrett Butler's agent, Isaac Pender, who refuses new leases to tenants. This and other injustices are received by the peasantry with restraint appropriate to contemporary respectable standards but they also illustrate a divided society.[40] The novel also provides a contrasting vision of a harmonious community, symbolically expressed in music.[41] James H. Murphy argues that this was the key to Knocknagow's popularity: "It presents Ireland both as a society riven with conflict and oppression...and as a society of harmony and celebration".[40] Vincent Comerford accounts for the novel's success with the lower middle class by claiming that they saw "an explanation of [their] own origins in a struggle against vicissitudes of insecurity of tenure".[42] For fifty years after its publication, Knocknagow was one of the most popular books in Ireland.[43] The young Michael Collins was once found weeping over the sufferings of the peasantry in the novel.[44] Aodh de Blácam called Knocknagow "the national Irish novel"[45] and claimed "Knocknagow will never die, unless the Irish nation dies".[46] Conclusion Liberty Square, Thurles, County Tipperary Charles Kickham was the author of three well-known stories, dealing sympathetically with Irish life and manners and the simple faith, the joys and sorrows, the quaint customs and the insuppressible humour of the peasantry. “Knocknagow,” or “The Homes of Tipperary,” one of the finest tales of peasant life ever written, suggests O’Sullivan. “Sally Cavanagh,” or “The Untenanted Graves,” a touching story illustrating the evils of landlordism and emigration; and “For the Old Land,” dealing with the fortunes of a small farmer's family, with its lights and shades.[4] John O’Leary was to say of Kickham in his Recollections of Fenians and Fenianism:[47]

John Devoy called him "the finest intellect in the Fenian movement, either in Ireland or in America."[38] Charles Kickham died on 22 August 1882, in his 54th year. He died at the house of James O'Connor (a former member of the IRB and afterwards M.P. for Wicklow) 2 Montpelier Place, Blackrock, Dublin, where he had been living for many years, and had been cared for by the poet Rose Kavanagh. He was buried in Mullinahone, County Tipperary.[4] Notes

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||