|

Charlemont, County Armagh

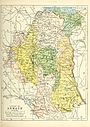

Charlemont (Irish: Achadh an Dá Chora, "field of the two weirs")[1] is a small village in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. It sits on the right bank of the River Blackwater, five miles northwest of Armagh, and is linked to the neighbouring village of Moy by Charlemont Bridge. It had a population of 109 people (52 households) at the 2011 Census.[2] HistoryCharlemont takes its name from Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy, who built a bridge and fort here in 1602 in order to secure the Blackwater valley against the rebel Earl of Tyrone.[3] Sir Toby Caulfeild became the fort's governor the following year.[4] By 1611, a "towne" had grown up around the fort, "replenished with many inhabitants of English and Irish, who have built them good houses of coples." It was incorporated as a borough in 1613.[5] Charlemont Fort retained its military significance after Tyrone's Rebellion came to an end. Caulfeild rebuilt the defences in 1622, adding a three-storied governor's house. At the outbreak of the 1641 Rebellion, the fort was taken by Sir Phelim O'Neill in a surprise attack. A number of attempts were made to recapture it, but despite the efforts of both Royalists and Covenanters it remained in O'Neill's hands until 1650, when a Cromwellian force ousted him after a bloody siege.[4] In 1664, William Caulfeild sold Charlemont Fort to the Crown for the sum of £3,500.[6] James II installed Teig O'Regan as the fort's governor in 1689, and spent a night here on his way to the Siege of Derry. It again came under siege in 1690 when Marshal Schomberg arrived, eventually forcing O'Regan to surrender.[4] Charlemont Fort continued to be garrisoned throughout the 18th century, but its usefulness waned thereafter and the government withdrew the last garrison in 1856. In 1859 it was sold to the Earl of Charlemont for £12,884 5s.[4] It was burned down by the IRA in 1920,[7] leaving only the gatehouse there today.[4] The TroublesOn 15 May 1976, the Ulster Volunteer Force launched two attacks on pubs in Charlemont. A bomb attack on Clancy's Bar left three Catholic civilians dead: 54-year-old Felix Clancy, 22-year-old Sean O'Hagan, and 41-year-old Robert McCullough.[8] Shortly after, a gun attack on the nearby Eagle Bar led to the death of another Catholic civilian: 49-year-old Frederick McLoughlin two weeks later.[9] A UDR soldier was later convicted for taking part in the attacks, which have been linked to the "Glenanne gang".[10] EducationSee also

References

|

||||||||||||