|

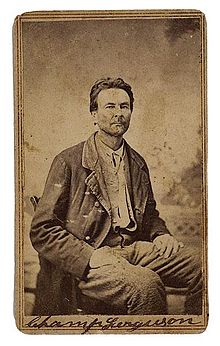

Champ Ferguson

Samuel "Champ" Ferguson (November 29, 1821 – October 20, 1865)[1] was a notorious Confederate guerrilla during the American Civil War. He claimed to have killed over 100 Union soldiers and pro-Union civilians.[2] He was arrested, tried, and executed for war crimes by the U.S. military after the war ended. Early lifeFerguson was born in Clinton County, Kentucky, on the Tennessee border, the oldest of ten children. This area was known as the Kentucky Highlands and had more families who were yeomen farmers and generally owned few slaves. Like his father, Ferguson became a farmer but also earned a reputation for violence even before the American Civil War. He became a slave owner in the 1850s.[3][4] On August 12, 1858, an altercation that culminated in a feud between Ferguson and the Evans brothers, Floyd and Alexander, resulted in the death of James Reed, the Evans' cousin and acting constable of Fentress County, Tennessee and the near death of Floyd Evans.[5] Both men were stabbed repeatedly by Ferguson as he attempted to flee mob justice, which the Tennesseans had meant to inflict on Ferguson after cornering him on their side of the border.[3] In the 1850s, Ferguson moved with his wife and family to the Calfkiller River Valley in White County, Tennessee. Guerrilla activities During the Civil War, East Tennessee, a mostly mountainous region, opposed secession from the Union.[6] The establishment in the region, for instance, of the "Free and Independent State of Scott" was an example of this.[7] The remainder of the state, which had more slaveholders, particularly in the plantation areas of West Tennessee, supported the Confederacy. The historical division made East Tennessee a target of informal engagements by both sides. Confederate troops fought engagements with local partisans, which took place far from the front.[8] From 1862, Tennessee was occupied by Union troops, which contributed to the tensions and divisions. The mountainous terrain and the lack of law enforcement during the war gave guerrillas and other irregular military groups significant freedom of action. Numerous incidents were recorded of guerrilla and revenge attacks, especially on the Cumberland Plateau. Families were often divided; one of Champ Ferguson's brothers fought as a member of the Union's 1st Kentucky Cavalry and was killed in action.[9]  Early in the war, Ferguson organized a guerrilla company and began attacking any civilians that he believed supported the Union. Many local vendettas were prosecuted in occupied Tennessee under the guise of war. His men cooperated with Confederate military units led by Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan and Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler when they were in the area and some evidence indicates that Morgan commissioned Ferguson as a captain of partisan rangers. Ferguson's men were seldom subject to military discipline and often violated the normal rules of war. Stories circulated about Ferguson's alleged sadism, including tales that he occasionally decapitated his prisoners and rolled their heads down hillsides. He was said to be willing to kill elderly and bedridden men. He was once arrested by the Confederate authorities and charged with murdering a government official and was imprisoned for two months in Wytheville, Virginia. The charges could not be proved, so he was eventually released.[7] Trial and hanging   At the war's end, Ferguson disbanded his men and returned home to his farm. As soon as the Union troops learned of his return, they arrested him and took him to Nashville, where he was tried by a military court for 53 murders. Ferguson's trial attracted national attention and soon became a major media event. One of Ferguson's main adversaries on the Union side, David "Tinker Dave" Beatty, testified against him.[10] Just as Ferguson had led a guerrilla band against any real or presumed Unionists, Beatty led a guerrilla band against any real or presumed confederates. Both did their best to ambush and kill the other. Ferguson acknowledged that his band had killed many of the victims named and said he had killed over 100 men himself. He insisted this conduct was simply part of his duty as a soldier.[2] A notorious incident was Ferguson and his guerrilla band's involvement in killing wounded Union men and prisoners after the Battle of Saltville. The victims were members of the all-black 5th United States Colored Cavalry and their white officers. Ferguson and his men were charged with murdering the wounded in their hospital beds. Only the arrival of Thomas' Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders had prevented the complete slaughter of the prisoners. As soon as Ferguson learned that regular Confederates had arrived, he left with his men.[11] On October 10, 1865, Ferguson was found guilty and sentenced to hang. He made a statement in response to the verdict:

He was hanged on October 20, 1865, one of only three men to be tried, convicted, and executed for war crimes during the Civil War. The others were Captain Henry Wirz, commandant of the infamous Andersonville prison in Georgia, and Henry C. Magruder, a Confederate guerrilla fighter who was convicted of eight murders.[12][13] Ferguson was buried in a comb grave in the France Cemetery north of Sparta, White County, Tennessee. This site is now bordered by Highway 84 (Monterey Highway). After his execution, Ferguson's statements to the Nashville Dispatch were published; The New York Times classified his letter as a confession. He admitted to killing at least ten people. Ferguson claimed nine of the men were killed in self-defense. He believed that one was committing murders and robbing private houses. Ferguson also stated that he had been convicted of the murders of several men who were killed by other members of his group. He denied some of the charges, including the killing of 12 soldiers at Saltville, and said that many of the men he was accused of killing had died in battle or been killed by bands other than his own. Ferguson felt that his trial had been neither just nor fair. Knowing that he would be sentenced to death, he questioned the reliability of all but two of the witnesses.[14] See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||