|

Carbene In organic chemistry, a carbene is a molecule containing a neutral carbon atom with a valence of two and two unshared valence electrons. The general formula is R−:C−R' or R=C: where the R represents substituents or hydrogen atoms. The term "carbene" may also refer to the specific compound :CH2, also called methylene, the parent hydride from which all other carbene compounds are formally derived.[1][2] There are two types of carbenes: singlets or triplets, depending upon their electronic structure.[3] The different classes undergo different reactions. Most carbenes are extremely reactive and short-lived. A small number (the dihalocarbenes, carbon monoxide,[4] and carbon monosulfide) can be isolated, and can stabilize as metal ligands, but otherwise cannot be stored in bulk. A rare exception are the persistent carbenes,[5] which have extensive application in modern organometallic chemistry. GenerationThere are two common methods for carbene generation. In α elimination, two substituents eliminate from the same carbon atom. This occurs with reagents with no good leaving groups vicinal to an acidic proton are exposed to strong base; for example, phenyllithium will abstract HX from a haloform (CHX3).[6] Such reactions typically require phase-transfer conditions.[citation needed] Molecules with no acidic proton can also form carbenes. A geminal dihalide exposed to organolithiums can undergo metal-halogen exchange and then eliminate a lithium salt to give a carbene, and zinc metal abstracts halogens similarly in the Simmons–Smith reaction.[7]

It remains uncertain if these conditions form truly free carbenes or a metal-carbene complex. Nevertheless, metallocarbenes so formed give the expected organic products.[7] In a specialized but instructive case, α-halomercury compounds can be isolated and separately thermolyzed. The "Seyferth reagent" releases CCl2 upon heating:

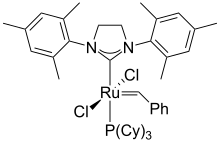

Separately, carbenes can be produced from an extrusion reaction with a large free energy change. Diazirines and epoxides photolyze with a tremendous release in ring strain to carbenes. The former extrude inert nitrogen gas, but epoxides typically give reactive carbonyl wastes, and asymmetric epoxides can potentially form two different carbenes. Typically, the C-O bond with lesser fractional bond order (fewer double-bond resonance structures) breaks. For example, when one substituent is alkyl and another aryl, the aryl-substituted carbon is usually released as a carbene fragment. Ring strain is not necessary for a strong thermodynamic driving force. Photolysis, heat, or transition metal catalysts (typically rhodium and copper) decompose diazoalkanes to a carbene and gaseous nitrogen; this occurs in the Bamford–Stevens reaction and Wolff rearrangement. As with the case of metallocarbenes, some reactions of diazoalkanes that formally proceed via carbenes may instead form a [3+2] cycloadduct intermediate that extrudes nitrogen.  To generate an alkylidene carbene a ketone can be exposed to trimethylsilyl diazomethane and then a strong base. Structures and bonding The two classes of carbenes are singlet and triplet carbenes. Triplet carbenes are diradicals with two unpaired electrons, typically form from reactions that break two σ bonds (α elimination and some extrusion reactions), and do not rehybridize the carbene atom. Singlet carbenes have a single lone pair, typically form from diazo decompositions, and adopt an sp2 orbital structure.[8] Bond angles (as determined by EPR) are 125–140° for triplet methylene and 102° for singlet methylene. Most carbenes have a nonlinear triplet ground state. For simple hydrocarbons, triplet carbenes are usually only 8 kcal/mol (33 kJ/mol) more stable than singlet carbenes, comparable to nitrogen inversion. The stabilization is in part attributed to Hund's rule of maximum multiplicity. However, strategies to stabilize triplet carbenes at room temperature are elusive. 9-Fluorenylidene has been shown to be a rapidly equilibrating mixture of singlet and triplet states with an approximately 1.1 kcal/mol (4.6 kJ/mol) energy difference, although extensive electron delocalization into the rings complicates any conclusions drawn from diaryl carbenes.[9] Simulations suggest that electropositive heteroatoms can thermodynamically stabilize triplet carbenes, such as in silyl and silyloxy carbenes, especially trifluorosilyl carbenes.[10] Lewis-basic nitrogen, oxygen, sulphur, or halide substituents bonded to the divalent carbon can delocalize an electron pair into an empty p orbital to stabilize the singlet state. This phenomenon underlies persistent carbenes' remarkable stability. ReactivityCarbenes behave like very aggressive Lewis acids. They can attack lone pairs, but their primary synthetic utility arises from attacks on π bonds, which give cyclopropanes; and on σ bonds, which cause carbene insertion. Other reactions include rearrangements and dimerizations. A particular carbene's reactivity depends on the substituents, including any metals present. Singlet-triplet effects Singlet and triplet carbenes exhibit divergent reactivity.[11][page needed][12] Triplet carbenes are diradicals, and participate in stepwise radical additions. Triplet carbene addition necessarily involves (at least one) intermediate with two unpaired electrons. Singlet carbenes can (and do) react as electrophiles, nucleophiles, or ambiphiles.[4] Their reactions are typically concerted and often cheletropic.[citation needed] Singlet carbenes are typically electrophilic,[4] unless they have a filled p orbital, in which case they can react as Lewis bases. The Bamford–Stevens reaction gives carbenes in aprotic solvents and carbenium ions in protic ones. The different mechanisms imply that singlet carbene additions are stereospecific but triplet carbene additions stereoselective. Methylene from diazomethane photolysis reacts with either cis- or trans-2-butene to give a single diastereomer of 1,2-dimethylcyclopropane: cis from cis and trans from trans. Thus methylene is a singlet carbene; if it were triplet, the product would not depend on the starting alkene geometry.[13] CyclopropanationCarbenes add to double bonds to form cyclopropanes,[14] and, in the presence of a copper catalyst, to alkynes to give cyclopropenes. Addition reactions are commonly very fast and exothermic, and carbene generation limits reaction rate. In Simmons-Smith cyclopropanation, the iodomethylzinc iodide typically complexes to any allylic hydroxy groups such that addition is syn to the hydroxy group. C—H insertionInsertions are another common type of carbene reaction,[15] a form of oxidative addition. Insertions may or may not occur in single step (see above). The end result is that the carbene interposes itself into an existing bond, preferably X–H (X not carbon), else C–H or (failing that) a C–C bond. Alkyl carbenes insert much more selectively than methylene, which does not differentiate between primary, secondary, and tertiary C-H bonds.   The 1,2-rearrangement produced from intramolecular insertion into a bond adjacent to the carbene center is a nuisance in some reaction schemes, as it consumes the carbene to yield the same effect as a traditional elimination reaction.[16] Generally, rigid structures favor intramolecular insertions. In flexible structures, five-membered ring formation is preferred to six-membered ring formation. When such insertions are possible, no intermolecular insertions are seen. Both inter- and intra-molecular insertions admit asymmetric induction from a chiral metal catalyst. Electrophilic attackCarbenes can form adducts with nucleophiles, and are a common precursor to various 1,3-dipoles.[16] Carbene dimerization Carbenes and carbenoid precursors can dimerize to alkenes. This is often, but not always, an unwanted side reaction; metal carbene dimerization has been used in the synthesis of polyalkynylethenes and is the major industrial route to Teflon (see Carbene § Industrial applications). Persistent carbenes equilibrate with their respective dimers, the Wanzlick equilibrium. Ligands in organometallic chemistryIn organometallic species, metal complexes with the formulae LnMCRR' are often described as carbene complexes.[17] Such species do not however react like free carbenes and are rarely generated from carbene precursors, except for the persistent carbenes.[citation needed][18] The transition metal carbene complexes can be classified according to their reactivity, with the first two classes being the most clearly defined:

Industrial applicationsA large-scale application of carbenes is the industrial production of tetrafluoroethylene, the precursor to Teflon. Tetrafluoroethylene is generated via the intermediacy of difluorocarbene:[22]

The insertion of carbenes into C–H bonds has been exploited widely, e.g. the functionalization of polymeric materials[23] and electro-curing of adhesives.[24] Many applications rely on synthetic 3-aryl-3-trifluoromethyldiazirines[25][26] (a carbene precursor that can be activated by heat,[27] light,[26][27] or voltage)[28][24] but there is a whole family of carbene dyes. HistoryCarbenes had first been postulated by Eduard Buchner in 1903 in cyclopropanation studies of ethyl diazoacetate with toluene.[29] In 1912 Hermann Staudinger[30] also converted alkenes to cyclopropanes with diazomethane and CH2 as an intermediate. Doering in 1954 demonstrated their synthetic utility with dichlorocarbene.[31] See also

References

External links

|