|

Canadian Coast Guard

The Canadian Coast Guard (CCG; French: Garde côtière canadienne, GCC) is the coast guard of Canada. Formed in 1962, the coast guard is tasked with marine search and rescue (SAR), communication, navigation, and transportation issues in Canadian waters, such as navigation aids and icebreaking, marine pollution response, and support for other Canadian government initiatives. The Coast Guard operates 119 vessels of varying sizes and 23 helicopters, along with a variety of smaller craft. The CCG is headquartered in Ottawa, Ontario, and is a special operating agency within Fisheries and Oceans Canada (Department of Fisheries and Oceans). Role and responsibility Unlike armed coast guards of some other nations, the CCG is a government marine organization without naval or law enforcement responsibilities. Naval operations in Canada's maritime environment are exclusively the responsibility of the Royal Canadian Navy. Enforcement of Canada's maritime-related federal statutes may be carried out by peace officers serving with various federal, provincial or even municipal law enforcement agencies.[citation needed] Although CCG personnel are neither a naval nor law enforcement force, they may operate CCG vessels in support of naval operations, or they may serve an operational role in the delivery of maritime law enforcement and security services in Canadian federal waters by providing a platform for personnel serving with one or more law enforcement agencies. The CCG's responsibility encompasses Canada's 202,080-kilometre-long (109,110 nmi; 125,570 mi) coastline. Its vessels and aircraft operate over an area of ocean and inland waters covering approximately 2.3 million square nautical miles (7.9 million square kilometres).[citation needed] Mission and mandate"Canadian Coast Guard services support government priorities and economic prosperity and contribute to the safety, accessibility and security of Canadian waters."[4] The CCG's mandate is stated in the Oceans Act and the Canada Shipping Act.[4] The Oceans Act gives the minister of Fisheries and Oceans responsibility for providing:

The Canada Shipping Act gives the minister powers, responsibilities and obligations concerning:

History

Predecessor agencies and formation (1867–1962)Originally a variety of federal departments and even the navy performed the work which the CCG does today. Following Confederation in 1867, the federal government placed many of the responsibilities for maintaining aids to navigation (primarily lighthouses at the time), marine safety, and search and rescue under the Marine Service of the Department of Marine and Fisheries, with some responsibility for waterways resting with the Canal Branch of the Department of Railways and Canals.  Lifeboat stations had been established on the east and west coasts as part of the Canadian Lifesaving Service; the station at Sable Island being one of the first in the nation. On the Pacific coast, the service operated the Dominion Lifesaving Trail (now called the West Coast Trail) which provided a rural communications route for survivors of shipwrecks on the treacherous Pacific Ocean coast off Vancouver Island. These stations maintained, sometimes sporadically in the earliest days, pulling (rowed) lifeboats crewed by volunteers and eventually motorized lifeboats. After the Department of Marine and Fisheries was split into separate departments, the Department of Marine continued to take responsibility for the federal government's coastal protection services. During the inter-war period, the Royal Canadian Navy also performed similar duties at a time when the navy was wavering on the point of becoming a civilian organization. Laws related to customs and revenue were enforced by the marine division of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. A government reorganization in 1936 saw the Department of Marine and its Marine Service, along with several other government departments and agencies, folded into the new Department of Transport. Following the Second World War, Canada experienced a major expansion in ocean commerce, culminating with the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1958. The shipping industry was changing throughout eastern Canada and required an expanded federal government role in the Great Lakes and the Atlantic coast, as well as an increased presence in the Arctic and Pacific coasts for sovereignty purposes. The government of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker decided to consolidate the duties of the Marine Service of the Department of Transport and on January 26, 1962, the Canadian Coast Guard was formed as a subsidiary of DOT. One of the more notable inheritances at the time of formation was the icebreaker Labrador, transferred from the Royal Canadian Navy. Expansion years (1962–1990) A period of expansion followed the creation of the CCG between the 1960s and the 1980s. The outdated ships the CCG inherited from the Marine Service were scheduled for replacement, along with dozens of new ships for the expanding role of the organization. Built under a complementary national shipbuilding policy which saw the CCG contracts go to Canadian shipyards, the new ships were delivered throughout this golden age of the organization. In addition to expanded geographic responsibilities in the Great Lakes, the rise in coastal and ocean shipping ranged from new mining shipments such as Labrador iron ore, to increased cargo handling at the nation's major ports, and Arctic development and sovereignty patrols—all requiring additional ships and aircraft. The federal government also began to develop a series of CCG bases near major ports and shipping routes throughout southern Canada, for example Victoria, British Columbia, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, and Parry Sound, Ontario. The expansion of the CCG fleet required new navigation and engineering officers, as well as crewmembers. To meet the former requirement, in 1965 the Canadian Coast Guard College (CCGC) opened on the former navy base HMCS Protector at Point Edward, Nova Scotia. By the late 1970s, the college had outgrown the temporary navy facilities and a new campus was opened in the adjacent community of Westmount in 1981.  During the mid-1980s, the long-standing disagreement between the U.S. and Canada over the legal status of the Northwest Passage came to a head after USCGC Polar Sea transited the passage in what were asserted by Canada to be Canadian waters and by the U.S. to be international waters. During the period of increased nationalism that followed this event, the Conservative administration of Brian Mulroney announced plans to build several enormous icebreakers, the Polar 8 class which would be used primarily for sovereignty patrols. However, the proposed Polar 8 class was abandoned during the late 1980s as part of general government budget cuts; in their place, a program of vessel modernizations was instituted. Additional budget cuts to CCG in the mid-1990s following a change in government saw many of CCG's older vessels built during the 1960s and 1970s retired. From its formation in 1962 until 1995, CCG was the responsibility of the Department of Transport. Both the department and CCG shared complementary responsibilities related to marine safety, whereby DOT had responsibility for implementing transportation policy, regulations and safety inspections, and CCG was operationally responsible for navigation safety and SAR, among others. Budget cuts and bureaucratic oversight (1994–2005)Following the 1995 Canadian federal budget, the federal government announced that it was transferring responsibility for the CCG from the Department of Transport to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). The reason for placing CCG under DFO was ostensibly to achieve cost savings by amalgamating the two largest civilian vessel fleets within the federal government under a single department. Arising out of this arrangement, the CCG became ultimately responsible for crewing, operating, and maintaining a larger fleet—both the original CCG fleet before 1995 of dedicated SAR vessels, Navaid tenders, and multi-purpose icebreakers along with DFO's smaller fleet of scientific research and fisheries enforcement vessels, all without any increase in budget—in fact the overall budget for CCG was decreased after absorbing the DFO patrol and scientific vessels. There were serious stumbling blocks arising out of this reorganization, namely in the different management practices and differences in organizational culture at DFO, versus DOT. DFO is dedicated to conservation and protection of fish through enforcement whereas the CCG's primary focus is marine safety and SAR. There were valid concerns raised within CCG about reluctance on the part of the marine community to ask for assistance from CCG vessels since the CCG was being viewed as aligned with an enforcement department. In the early 2000s, the federal government began to investigate the possibility of remaking CCG as a separate agency, thereby not falling under a specific functional department and allowing more operational independence. Special operating agency (2005–present)In one of several reorganizations of the federal ministries following the swearing-in of Prime Minister Paul Martin's cabinet on December 12, 2003, several policy/regulatory responsibilities (including boating safety and navigable waters protection) were transferred from CCG back to Transport Canada to provide a single point of contact for issues related to marine safety regulation and security, although CCG maintained an operational role for some of these tasks. The services offered by CCG under this arrangement include:

On April 4, 2005, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans designated the CCG as a "special operating agency"—the largest one in the federal government. Although the CCG still falls under the ministerial responsibility of the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, it has more autonomy where it is not as tightly integrated within the department. An example is that all CCG bases, aids to navigation, vessels, aircraft, and personnel are wholly the responsibility of the commissioner of the Canadian Coast Guard, who is also of assistant deputy ministerial rank. The commissioner is, in turn, supported by the CCG headquarters, which develops a budget for the organization. The arrangement is not unlike the relationship of the RCMP, also headed by a commissioner, toward that organization's parent department, the Department of Public Safety. On December 6, 2019, Mario Pelletier was appointed Commissioner of the Canadian Coast Guard. The special operating agency reorganization is different from the past under both DOT and DFO, where regional directors general for these departments were responsible for CCG operations within their respective regions; this reportedly caused problems under DFO that did not occur under DOT. Now all operations of CCG are directed by the commissioner, who reports directly to the deputy minister of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Assistant commissioners are responsible for CCG operations within each region and they report directly to the commissioner. This management and financial flexibility is being enhanced by an increased budget for CCG to acquire new vessels and other assets to assist in its growing role in marine security.  CCG continues to provide vessels and crew for supporting DFO's fisheries science, enforcement, conservation, and protection requirements. The changes resulting in CCG becoming a special operating agency under DFO did not address some of the key concerns raised by an all-party Parliamentary committee investigating low morale among CCG employees following the transfer from DOT to DFO and budget cuts since 1995. This committee had recommended that CCG become a separate agency under DOT and that its role be changed to that of an armed, paramilitary organization involved in maritime security by arming its vessels with deck guns, similar to the United States Coast Guard, and that employees be given peace officer status for enforcing federal laws on the oceans and Great Lakes. As a compromise, the CCG now partners with the RCMP and CBSA to create IBETs, which patrol Canadian waters along the Canada–United States border. Fleet modernization (1990–present)In the 1990s–2000s, CCG modernized part of its SAR fleet after ordering British Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI)-designed Arun-class high-endurance lifeboat cutters for open coastal areas, and the USCG-designed 47-foot Motor Lifeboat (designated by CCG as the Cape class) as medium-endurance lifeboat cutters for the Great Lakes and more sheltered coastal areas. The CCG ordered five 47-foot (14.3 m) motor lifeboats in September 2009, to add to the 31 existing boats.[7] New vessels delivered to the CCG from 2009 onward included the hovercraft CCGS Mamilossa[8] and the near-shore fisheries research vessels CCGS Kelso[9] and CCGS Viola M. Davidson.[10] Several major vessels have undergone extensive refits in recent decades, most notably CCGS Louis S. St-Laurent in place of procuring the Polar 8 class of icebreakers.  In the first decade of the 21st century, CCG announced plans for the Mid Shore Patrol Vessel Project (a class of nine vessels)[11][12][13][14] as well as a "Polar"-class icebreaker – since named CCGS Arpatuuq – in addition to inshore and offshore fisheries science vessels and a new oceanographic research vessel as part of efforts to modernize the fleet. In 2012, the Government of Canada announced procurement of 24 helicopters to replace the current fleet.[15] Modernizing the Coast Guard's icebreakersThe Coast Guard has acknowledged that it is not just Louis S. St. Laurent that is old, and needs replacing, all its icebreakers are old. Some critics have argued that with global warming, and the scramble for Arctic nations to document claims to a share of the Arctic Ocean seafloor, Canada lacked sufficient icebreakers. In 2018 the Coast Guard started to publicly search for existing large, capable icebreakers it could purchase. On August 13, 2018, the Coast Guard confirmed it would be buying and retrofitting three large, icebreaking, anchor-handling tugs, Tor Viking, Balder Viking and Vidar Viking from Viking Supply Ships.[16][17] On 22 May 2019, it was announced two more Harry DeWolf-class offshore patrol vessels will be built for the Canadian Coast Guard, in addition to the six being constructed for the Royal Canadian Navy.[18] Additionally, $15.7B was announced for the production of 16 additional multi-purpose vessels.[19] Organizational structureCCG's management and organizational structure reflects its quasi-military nature. The CCG agency supports several functional departments as outlined here:

Quasi-military structureThe Canadian Coast Guard is a civilian organization that is managed and funded by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). The enforcement of laws in Canada's territorial sea is the responsibility of Canada's federal police force, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) as all ocean waters in Canada are under federal (not provincial) jurisdiction. Saltwater fisheries enforcement is a specific responsibility of DFO's Fisheries Officers. CCG does not have a conventional paramilitary rank structure; instead, its rank structure roughly approximates that of the civilian merchant marine. In late October 2010 the Stephen Harper government tabled a report that recommended that arming Canadian Coast Guard icebreakers should be considered.[20] Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Gail Shea presented the government's response to a December 2009 report from the Senate's Fisheries Committee, entitled "Controlling Canada's Arctic Waters: Role of the Canadian Coast Guard."[21] The Senate Committee's report had also recommended arming Canadian Coast Guard vessels in the Arctic. Randy Boswell, of the Canwest News Service quoted Michael Byers, an expert on the law of the sea, who used the phrase "quiet authority of a deck-mounted gun".[20] Operational regions CCG as a whole is divided into four operational regions: Atlantic, Central, Western, and Arctic.[22] The newest region, the Arctic, was established in October 2018. Previously responsibility for the Arctic areas of Canada was split between the three existing regions. The new unit includes a mandate which ensures increased support for Inuit communities, including search and rescue, icebreaking and for community resupply. The new region is headquartered in Yellowknife.[23] AuxiliaryThe CCG does not have a "reserve" element. There is a Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary (CCGA) which is a separate non-profit organization composed of some 5,000 civilian volunteers across Canada who support search and rescue activities. The CCGA, formerly the Canadian Marine Rescue Auxiliary (CMRA), is made up of volunteer recreational boaters and commercial fishermen who assist CCG with search and rescue as well as boating safety education. CCGA members who assist in SAR operations have their vessel insurance covered by CCG, as well as any fuel and operating costs associated with a particular tasking. The CCGA enables the CCG to provide marine SAR coverage in many isolated areas of Canada's coastlines without having to maintain an active base and/or vessels in those areas. CommissionerThe head of CCG is called the "Commissioner of the Canadian Coast Guard". The rank of "Commissioner" is used in other Canadian federal agencies, such as the RCMP. However, rank and associated insignia are viewed differently in the CCG than in the Royal Canadian Navy.

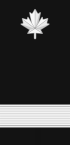

FacilitiesBases and stations Lighthouses CCG operates one of the largest networks of navigational buoys, lighthouses and foghorns in the world. These facilities assist marine navigation on the Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic coasts as well as selected inland waterways. CCG represents Canada at the International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities (IALA). CCG completed a large-scale program of lighthouse automation and de-staffing which began in 1968 and was largely completed in the 1990s.[27] The result of this program saw the automation of all lighthouses and the removal of light keepers except for a handful of stations in British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador and New Brunswick. Budget cuts and technological changes in the marine shipping industry, such as the increased use of GPS, electronic navigation charts and the Global Maritime Distress Safety System, has led CCG to undertake several service reviews for aids to navigation in recent decades. Such reviews have resulted in the further decommissioning of buoys and shore-based light stations as well as a dramatic reduction in the number of foghorns.[28] Canadian lightkeepers were notified September 1, 2009 that upper management was once again commencing the de-staffing process. The first round, to be completed before the end of the fiscal year, was to include Trial Island, Entrance Island, Cape Mudge and Dryad Point. The second round included Green Island, Addenbroke, Carmanah Point, Pachena Pt and Chrome Island. The decision was taken without input or consultation from the public or user-groups in spite of the fact that during the last round of de-staffing the public and user-groups spoke vocally against cuts to this service. Once again a large outcry forced Minister of Fisheries Gail Shea to respond and on September 30, 2009, she suspended the de-staffing process pending a review of services lightkeepers provide.[29] Historic facilitiesThe Department of Fisheries and Oceans, on behalf of the Canadian Coast Guard, is the custodian of many significant heritage buildings, including the oldest lighthouse in North America, the Sambro Island Lighthouse. The department has selectively maintained some heritage lighthouses and permitted some alternative use of its historic structures. However, many historic buildings have been neglected and the department has been accused of ignoring and abandoning even federally recognized buildings. Critics have pointed out that the department has lagged far behind other nations such as the United States in preserving its historic lighthouses.[30] These concerns have led community groups and heritage building advocates to promote the Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act in the Canadian Parliament.[28] Equipment Navigational aid and servicesThe Canadian Coast Guard produces the Notice to Mariners (NOTMAR) publication which informs mariners of important navigational safety matters affecting Canadian waters. This electronic publication is published on a monthly basis and can be downloaded from the Notices to Mariners website. The information in the Notice to Mariners is formatted to simplify the correction of paper charts and navigational publications published by the Canadian Hydrographic Service. Rank insignia and badgesEpaulettesMilitary epaulettes are used to represent ranks. In the CCG they represent levels of responsibility and commensurate salary levels. The Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary epaulettes are similar except they use silver braid to distinguish them from the Canadian Coast Guard.

Branch is denoted by coloured cloth between the gold braid. Deck officers, helicopter pilots, hovercraft pilots and JRCC/MRSC marine SAR controllers do not wear any distinctive cloth.

Auxiliary epaulettes

Cap badges

Qualification insigniaMedals, awards, and long service pins

Insignias and other representationsAs a special operating agency within the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, the CCG uses generic identifiers imposed by the Federal Identity Program. However, the CCG is one of several federal departments and agencies (primarily those involved with law enforcement, security, or having a regulatory function) that have been granted heraldic symbols.[citation needed] The CCG badge was originally approved in 1962.[1] Blue symbolizes water, white represents ice, and dolphins are considered a friend of mariners. The Latin motto Saluti Primum, Auxilio Semper translates as "Safety First, Service Always".[41] In addition to the Coast Guard jack,[40] distinctive flags have been approved for use by senior CCG officials, including the Honorary Chief Commissioner (the Governor General) and the Minister of Transport.[42] The Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary was granted a flag and badge by the Canadian Heraldic Authority in 2012.[43] See also

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Canadian Coast Guard. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||