|

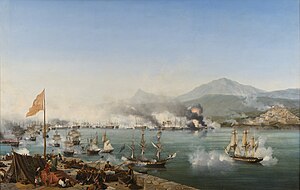

British foreign policy in the Middle EastBritish foreign policy in the Middle East has involved multiple considerations, particularly over the last two and a half centuries. These included maintaining access to British India, blocking Russian or French threats to that access, protecting the Suez Canal, supporting the declining Ottoman Empire against Russian threats, guaranteeing an oil supply after 1900 from Middle East fields, protecting Egypt and other possessions in the Middle East, and enforcing Britain's naval role in the Mediterranean. The timeframe of major concern stretches from the 1770s when the Russian Empire began to dominate the Black Sea, down to the Suez Crisis of the mid-20th century and involvement in the Iraq War in the early 21st. These policies are an integral part of the history of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom.  Napoleon's threatNapoleon, the leader of the French wars against Britain from the late 1790s until 1815, used the French fleet to convey a large invasion army to Egypt, a major remote province of the Ottoman Empire. British commercial interests represented by the Levant Company had a successful base in Egypt, and indeed the company handled all Egypt's diplomacy. The British responded and sank the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, thereby trapping Napoleon's army.[1] Napoleon escaped. The Army he left behind was defeated by the British and the survivors returned to France in 1801. In 1807 when Britain was at war with the Ottomans, the British sent a force to Alexandria, but it was defeated by the Egyptians under Mohammed Ali and withdrew. Britain absorbed the Levant company into the Foreign Office by 1825.[2][3] Greek independence: 1821–1833 Europe was generally peaceful; the Greek's long war of independence was the major military conflict in the 1820s.[4] Serbia had gained its autonomy from Ottoman Empire in 1815. The Greek rebellion came next starting in 1821, with a rebellion indirectly sponsored by Russia. The Greeks had strong intellectual and business communities which employed propaganda echoing the French Revolution that appealed to the romanticism of Western Europe. Despite harsh Ottoman reprisals they kept their rebellion alive. Sympathizers like British poet Lord Byron played a major role in shaping British opinion to strongly favor the Greeks, especially among Philosophical Radicals, the Whigs, and the Evangelicals.[5] However, the top British foreign policy makers George Canning (1770–1827) and Viscount Castlereagh (1769–1822) were much more cautious. They agreed that the Ottoman Empire was "barbarous" but they decided it was a necessary evil. British policy down to 1914 was to preserve the Ottoman Empire, especially against hostile pressures from Russia. However, when Ottoman behavior was outrageously oppressive against Christians, London demanded reforms and concessions.[6][7][8] The context of the three Great Powers' intervention was Russia's long-running expansion at the expense of the decaying Ottoman Empire. However, Russia's ambitions in the region were seen as a major geostrategic threat by the other European powers. Austria feared the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire would destabilize its southern borders. Russia gave strong emotional support for the fellow Orthodox Christian Greeks. The British were motivated by strong public support for the Greeks. The government in London paid special attention to the powerful role of the Royal Navy throughout the entire Mediterranean region. Fearing unilateral Russian action in support of the Greeks, Britain and France bound Russia by treaty to a joint intervention which aimed to secure Greek autonomy whilst preserving Ottoman territorial integrity as a check on Russia.[9] The Powers agreed, by the Treaty of London (1827), to force the Ottoman government to grant the Greeks autonomy within the empire and despatched naval squadrons to Greece to enforce their policy.[10] The decisive Allied naval victory at the Battle of Navarino broke the military power of the Ottomans and their Egyptian allies. Victory saved the fledgling Greek Republic from collapse. But it required two more military interventions, by Russia in the form of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29 and by a French expeditionary force to the Peloponnese to force the withdrawal of Ottoman forces from central and southern Greece and to finally secure Greek independence.[11] Greek nationalists proclaimed a new "Great Idea" whereby the little nation of 800,000 would expand to include all the millions of Greek Orthodox believers in the region now under Ottoman control, with Constantinople to be reclaimed as its capital. This idea was the antithesis of the British goal of maintaining the Ottoman Empire, and London systematically opposed the Greeks until the "Great Idea" finally collapsed in 1922 when Turkey drove the Greeks out of Anatolia.[12] Crimean WarThe Crimean War (from 1853 to 1856) was a major conflict fought in the Crimean Peninsula.[13] The Russian Empire lost to an alliance made up of Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire.[14] The immediate causes of the war were minor. The longer-term causes involved the decline of the Ottoman Empire and Russia's misunderstanding of the British position. Tsar Nicholas I visited London in person and consulted with Foreign Secretary Lord Aberdeen regarding what would happen if the Ottoman Empire collapsed and had to be split up. The tsar misread Britain’s position as supporting Russian aggression, while London actually sided with Paris against any breakup of the Ottoman Empire and Russian expansion. When Aberdeen became Prime Minister in 1852, the tsar mistakenly believed he had British approval for action against Turkey and was shocked when Britain declared war. Despite Aberdeen's opposition to the war, public opinion demanded it, leading to his resignation.[15] The new prime minister was Lord Palmerston who strongly opposed Russia. He defined the popular imagination which saw the war against Russia is a commitment to British principles, notably the defense of liberty, civilization, free trade; and championing the underdog. The fighting was largely limited to actions in the Crimean Peninsula and the Black Sea. Both sides badly mishandled operations; the world was aghast at the extremely high death rates due to disease. In the end, the British-French coalition prevailed and Russia lost control of the Black Sea. Russia in 1871 regained control of the Black Sea.[16][17][18] Pompous aristocracy was a loser in the war, the winners were the ideals of middle-class efficiency, progress, and peaceful reconciliation. The war's great hero was Florence Nightingale, the nurse who brought scientific management and expertise to heal the horrible sufferings of the tens of thousands of sick and dying British soldiers.[19] according to historian R. B. McCallum the Crimean War:

Seizure of Egypt, 1882As owners of the Suez Canal, both British and French governments had strong interests in the stability of Egypt. Most of the traffic was by British merchant ships. However, in 1881 the ʻUrabi revolt broke out-- it was a nationalist movement led by Ahmed ʻUrabi (1841–1911) against the administration of Khedive Tewfik, who collaborated closely with the British and French. Combined with the complete turmoil in Egyptian finances, the threat to the Suez Canal, and embarrassment to British prestige if it could not handle a revolt, London found the situation intolerable and decided to end it by force.[21] The French, however, did not join in. On 11 July 1882, Prime Minister William E. Gladstone ordered the bombardment of Alexandria which launched the short decisive Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882.[22][23] Egypt nominally remained under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire, and France and other nations had representation, but British officials made the decisions. The Khedive (Viceroy) was the Ottoman official in Cairo, appointed by the Sultan in Constantinople. He appointed the Council of ministers and high-ranking military officer; he controlled the treasury and sign treaties. In practice he operated under the close supervision of the British consul general. The dominant personality was Consul-general Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer (1841–1917). He was thoroughly familiar with the British Raj in India, and applied similar policies to take full control of the Egyptian economy. London repeatedly promised to depart in a few years. It did so 66 times until 1914, when it gave up the pretense and assumed permanent control.[24][25] Historian A.J.P. Taylor says that the seizure of Egypt "was a great event; indeed, the only real event in international relations between the Battle of Sedan and the defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese war."[26] Taylor emphasizes long-term impact:

Gladstone and the Liberals had a reputation for strong opposition to imperialism, so historians have long debated the explanation for this reversal of policy. The most influential was a study by John Robinson and Ronald Gallagher, Africa and the Victorians (1961). They focused on The Imperialism of Free Trade and promoted the highly influential Cambridge School of historiography. They argue that the Liberals had no long-term plan for imperialism but acted out of necessity to protect the Suez Canal amid a nationalist revolt and the threat to law and order in Egypt. Gladstone's decision was influenced by strained relations with France and the actions of British officials in Egypt. Critics like Cain and Hopkins emphasize the need to protect British financial investments in Egypt, downplaying the risks to the Suez Canal. Unlike Marxists, they focus on "gentlemanly" financial interests rather than industrial capitalism.[28] A.G. Hopkins rejected Robinson and Gallagher's argument, citing original documents to claim that there was no perceived danger to the Suez Canal from the ‘Urabi movement, and that ‘Urabi and his forces were not chaotic "anarchists", but rather maintained law and order.[29] : 373–374 He argues that Gladstone's cabinet was motivated by the need to protect British bondholders' investments in Egypt and to gain domestic political popularity. Hopkins points to the significant growth of British investments in Egypt, driven by the Khedive's debt from the Suez Canal's construction, and the close ties between the British government and the economic sector.[29]: 379–380 He writes that Britain's economic interests occurred simultaneously with a desire within one element of the ruling Liberal Party for a militant foreign policy in order to gain the domestic political popularity that enabled it to compete with the Conservative Party.[29]: 382 Hopkins cites a letter from Edward Malet, the British consul general in Egypt at the time, to a member of the Gladstone Cabinet offering his congratulations on the invasion: "You have fought the battle of all Christendom and history will acknowledge it. May I also venture to say that it has given the Liberal Party a new lease of popularity and power."[29]: 385 However, Dan Halvorson argues that the protection of the Suez Canal and British financial and trade interests were secondary and derivative. Instead, the primary motivation was the vindication of British prestige in both Europe and especially in India by suppressing the threat to "civilised" order posed by the Urabist revolt.[30][31] ArmeniaThe Ottoman Empire leadership had long been hostile to its Armenian element, and in World War I accused it of favouring Russia. The result was an attempt to relocate Armenians in which hundreds of thousands died in the Armenian genocide.[32] Since the late 1870s Gladstone had moved Britain into playing a leading role in denouncing the harsh policies and atrocities and mobilizing world opinion. In 1878–1883 Germany followed the lead of Britain in adopting an Eastern policy that demanded reforms in the Ottoman policies that would ameliorate the position of the Armenian minority.[33] Persian Gulf In 1650, British diplomats signed a treaty with the Sultan at Oman declaring that the bond between the two nations should be "unshook to the end of time."[34] British policy was to expand its presence in the Persian Gulf region, with a strong base in Oman. Two London-based companies were used, first the Levant Company and later the East India Company. The shock of Napoleon's 1798 expedition to Egypt led London to significantly strengthen its ties in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, pushing out the French and Dutch rivals, and upgrading the East India Company operations to diplomatic status. The East India Company also expanded relations with other sultanates in the region, and expanded operations into southern Persia. There was something of a standoff with Russian interests, which were active in northern Persia.[35] The commercial agreements allowed for British control of mineral resources, but the first oil was discovered in the region in Persia in 1908. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company activated the concession and quickly became the Royal Navy's main source of fuel for the new diesel engines that were replacing coal-burning steam engines. The company merged into BP (British Petroleum). The main advantage of oil was that a warship could easily carry fuel for long voyages without having to make repeated stops at coaling stations.[36][37][38] AdenWhen Napoleon threatened Egypt in 1798, one of his threats was to cut off British access to India. In response the East India Company (EIC) negotiated an agreement with Aden’s sultan that provided rights to the deepwater harbor on Arabia's southern coast including a strategically important coaling station. The EIC took full control in 1839. With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, Aden took a much greater strategic an economic importance. To protect against threats from the Ottoman Empire, the EIC negotiated agreements with sheikhs in the hinterland, and by 1900 had absorbed their territory. Local demands for independence led in 1937 to designation of Aden as a Crown Colony separate from India.[39] Nearby areas were consolidated as the Western Aden protectorate and Eastern Aden protectorate. Some 1300 sheikhs and chieftains signed agreements and remained in power locally. They resisted demands from leftist labor unions based in the ports and refineries, and strongly opposed the threat of Yemen to incorporate them.[40] London considered the military base and Aiden as essential to protect its oil interest in the Persian Gulf. Expenses mounted, budgets were cut, and London misinterpreted the mounting internal conflicts.[41] In 1963 the Federation of South Arabia was set up that merged the colony and 15 of the protectorates. Independence was announced, leading to the Aden Emergency--a civil war involving Soviet-backed National Liberation Front fighting the Egyptian-backed Front for the Liberation of Occupied South Yemen. In 1967 the Labour government under Harold Wilson withdrew its forces from Aden. The National Liberation Front quickly took power and announced the creation of a communist People’s Republic of South Yemen, deposing the traditional leaders in the sheikhdoms and sultanates. It was merged with Yemen into People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, with close ties to Moscow.[42][43][44] World War I era World War IThe Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of Germany and immediately became an enemy of Britain and France. Four major Allied operations attacked the Ottoman holdings.[45] The Gallipoli Campaign to control the Straits failed in 1915-1916. The first Mesopotamian campaign invading Iraq from India also failed. The second one captured Baghdad in 1917. The Sinai and Palestine campaign from Egypt was a British success. By 1918 the Ottoman Empire was a military failure/ It signed an armistice in late October that amounted to surrender.[46] Partition of Ottoman EmpireThe partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 1918 – 1 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred after World War I and the occupation of Istanbul by British, French, and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was planned in several agreements made by the Allied Powers early in the course of World War I,[47] notably the Sykes–Picot Agreement, after the Ottoman Empire had joined Germany to form the Ottoman–German Alliance.[48] The huge conglomeration of territories and peoples that formerly comprised the Ottoman Empire was divided into several new states.[49] The Ottoman Empire had been the leading Islamic state in geopolitical, cultural and ideological terms. The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the war led to the domination of the Middle East by Western powers such as Britain and France, and saw the creation of the modern Arab world and the Republic of Turkey. Resistance to the influence of these powers came from the Turkish National Movement but did not become widespread in the other post-Ottoman states until the period of rapid decolonization after World War II. The sometimes-violent creation of protectorates in Iraq and Palestine, and the proposed division of Syria along communal lines, is thought to have been a part of the larger strategy of ensuring tension in the Middle East, thus necessitating the role of Western colonial powers (at that time Britain, France and Italy) as peace brokers and arms suppliers.[50] The League of Nations mandate granted the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, the British Mandate for Mesopotamia (later Iraq) and the British Mandate for Palestine, later divided into Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan (1921–1946). The Ottoman Empire's possessions in the Arabian Peninsula became the Kingdom of Hejaz, which the Sultanate of Nejd (today Saudi Arabia) was allowed to annex, and the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen. The Empire's possessions on the western shores of the Persian Gulf were variously annexed by Saudi Arabia (al-Ahsa and Qatif), or remained British protectorates (Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar) and became the Arab States of the Persian Gulf. Postwar planningIn the 1920s, British policymakers debated two alternative approaches to Middle Eastern issues. Many diplomats adopted the line of thought of T. E. Lawrence favoring Arab national ideals. They backed the Hashemite family for top leadership positions. The other approach led by Arnold Wilson, the civil commissioner for Iraq, reflected the views of the India office. They argue that direct British rule was essential, and the Hashemite family was too supportive of policies that would interfere with British interests. The decision was to support Arab nationalism, sidetracked Wilson, and consolidate power in the Colonial Office. [51][52][53] New British Mandates and coloniesThe British were awarded three mandated territories, with one of Sharif Hussein's sons, Faisal, installed as King of Iraq and Transjordan providing a throne for another of Hussein's sons, Abdullah. Mandatory Palestine was placed under direct British administration, and the Jewish population was allowed to increase, initially under British protection. Most of the Arabian peninsula fell to another British ally, Ibn Saud, who created the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932. Mandate for MesopotamiaMosul was allocated to France under the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement and was subsequently given to Britain under the 1918 Clemenceau–Lloyd George Agreement. Great Britain and Turkey disputed control of the former Ottoman province of Mosul in the 1920s. Under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne Mosul fell under the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, but the new Turkish republic claimed the province as part of its historic heartland. A three-person League of Nations committee went to the region in 1924 to study the case and in 1925 recommended the region remain connected to Iraq, and that the UK should hold the mandate for another 25 years, to assure the autonomous rights of the Kurdish population. Turkey rejected this decision. Nonetheless, Britain, Iraq and Turkey made a treaty on 5 June 1926, that mostly followed the decision of the League Council. Mosul stayed under British Mandate of Mesopotamia until Iraq was granted independence in 1932 by the urging of King Faisal, though the British retained military bases and transit rights for their forces in the country. Mandate for Palestine During the Great War, Britain produced three contrasting, but feasibly compatible, statements regarding their ambitions for Palestine. Britain had supported, through British intelligence officer T. E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia), the establishment of a united Arab state covering a large area of the Arab Middle East in exchange for Arab support of the British during the war. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 encouraged Jewish ambitions for a national home. Lastly, the British promised via the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence that the Hashemite family would have lordship over most land in the region in return for their support in the Great Arab Revolt. The Arab Revolt, which was in part orchestrated by Lawrence, resulted in British forces under General Edmund Allenby defeating the Ottoman forces in 1917 in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign and occupying Palestine and Syria. The land was administered by the British for the remainder of the war. The United Kingdom was granted control of Palestine by the Versailles Peace Conference which established the League of Nations in 1919. Herbert Samuel, a former Postmaster General in the British cabinet who was instrumental in drafting the Balfour Declaration, was appointed the first High Commissioner in Palestine. In 1920 at the San Remo conference, in Italy, the League of Nations mandate over Palestine was assigned to Britain. In 1923 Britain transferred a part of the Golan Heights to the French Mandate of Syria, in exchange for the Metula region. IraqThe British seized Baghdad in March 1917. In 1918 it was joined to Mosul and Basra in the new nation of Iraq using a League of Nations Mandate. Experts from India designed the new system, which favoured direct rule by British appointees, and demonstrated distrust of the aptitude of local Arabs for self-government. The old Ottoman laws were discarded and replaced by new codes for civil and criminal law, based on Indian practice. The Indian rupee became the currency. The army and police were staffed with Indians who had proven their loyalty to the British Raj.[54] The large-scale Iraqi revolt of 1920 was crushed in the summer of 1920 but it was a major stimulus for Arab nationalism.[55] The Turkish Petroleum Company was given a monopoly on exploration and production in 1925. Important oil reserves were First discovered in 1927; the name was changed to the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) in 1929. It was owned by a consortium of British, French, Dutch and American oil companies, and operated by the British until it was nationalized in 1972. The British ruled under the League mandate from 1918 to 1933. Formal independence was granted in 1933, but with a very powerful British presence in the background.[56] World War IIIraqThe Anglo–Iraqi War (2–31 May 1941) was a British military campaign to regain control of Iraq and its major oil fields.[57] Rashid Ali had seized power in 1941 with assistance from Germany. The campaign resulted in the downfall of Ali's government, the re-occupation of Iraq by the British, and the return to power of the Regent of Iraq, Prince 'Abd al-Ilah, a British ally.[58][59] The British launched a large pro-democracy propaganda campaign in Iraq from 1941–5. It promoted the Brotherhood of Freedom to instil civic pride in disaffected Iraqi youth. The rhetoric demanded internal political reform and warned against growing communist influence. Heavy use was made of the Churchill-Roosevelt Atlantic Charter. However, leftist groups adapted the same rhetoric to demand British withdrawal. Pro-Nazi propaganda was suppressed. The heated combination of democracy propaganda, Iraqi reform movements, and growing demands for British withdrawal and political reform became as a catalyst for postwar political change.[60][61] In 1955, the United Kingdom was part of the Baghdad Pact with Iraq. King Faisal II of Iraq paid a state visit to Britain in July 1956.[62] The British had a plan to use 'modernisation' and economic growth to solve Iraq's endemic problems of social and political unrest. The idea was that increased wealth through Oil production would ultimately trickle down to all elements and thereby thus stave off the danger of revolution. The oil was produced but the wealth never reached below the elite. Iraq's political-economic system put unscrupulous politicians and wealthy landowners at the apex of power. The remained in control using an all-permeating patronage system. As a consequence very little of the vast wealth was dispersed to the people, and unrest continue to grow.[63] In 1958, monarch and politicians were swept away in a vicious nationalist army revolt. Suez Crisis of 1956The Suez Crisis of 1956 was a major disaster for British (and French) foreign policy and left Britain a minor player in the Middle East because of very strong opposition from the United States. The key move was an invasion of Egypt in late 1956 first by Israel, then by Britain and France. The aims were to regain Western control of the Suez Canal and to remove Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had just nationalised the canal. After the fighting had started, intense political pressure and economic threats from the United States, plus criticism from the Soviet Union and the United Nations forced a withdrawal by the three invaders. The episode humiliated the United Kingdom and France and strengthened Nasser. The Egyptian forces were defeated, but they did block the canal to all shipping. The three allies had attained a number of their military objectives, but the canal was useless. U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower had strongly warned Britain not to invade; he threatened serious damage to the British financial system by selling the US government's pound sterling bonds. The Suez Canal was closed from October 1956 until March 1957, causing great expense to British shipping interests. Historians conclude the crisis "signified the end of Great Britain's role as one of the world's major powers".[64][65][66] East of SuezAfter 1956, the well-used rhetoric of the British role East of Suez was less and less meaningful. The independence of India, Malaya, Burma and other smaller possessions meant London had little role, and few military or economic assets to back it up. Hong Kong was growing in importance but it did not need military force. Labour was in power but both parties agreed on the need to cut the defence budget and redirect attention to Europe and NATO, so the forces were cut east of Suez. [67][68][69] See also

Notes

Further reading

Historiography

Primary sources

External links |