|

Bradshaw's Guide

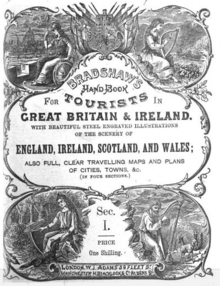

Bradshaw's was a series of railway timetables and travel guide books published by W.J. Adams and later Henry Blacklock, both of London. They are named after founder George Bradshaw, who produced his first timetable in October 1839. Although Bradshaw died in 1853, the range of titles bearing his name (and commonly referred to by that alone) continued to expand for the remainder of the 19th and early part of the 20th century, covering at various times Continental Europe, India, Australia and New Zealand, as well as parts of the Middle-East. They survived until May 1961, when the final monthly edition of the British guide was produced.[1][2][3] The British and Continental guides were referred to extensively by presenter Michael Portillo in his multiple television series.[a] Early historyBradshaw's name was already known as the publisher of Bradshaw's Maps of Inland Navigation, which detailed the canals of Lancashire and Yorkshire, when, on 19 October 1839, soon after the introduction of railways, his Manchester company published the world's first compilation of railway timetables. The cloth-bound book was entitled Bradshaw's Railway Time Tables and Assistant to Railway Travelling and cost sixpence. In 1840 the title was changed to Bradshaw's Railway Companion, and the price raised to one shilling.[4] A new volume was issued at occasional intervals and from time to time a supplement kept this up to date. The original Bradshaw publications were published before the limited introduction of standardised Railway time in November 1840, and its subsequent development into standard time. The accompanying map of all lines in operation (and some "in progress") in England and Wales, is cited as being the world's first national railway map.[5]  In December 1841, acting on a suggestion made by his London agent, William Jones Adams, Bradshaw reduced the price to the original sixpence, and began to issue the guides monthly under the title Bradshaw's Monthly Railway Guide. [4] Many railway companies were unhappy with Bradshaw's timetable, but Bradshaw was able to circumvent this by becoming a railway shareholder and by putting his case at company AGMs.[6] Soon the book, in the familiar yellow wrapper,[7] became synonymous with its publisher: for Victorians and Edwardians alike, a railway timetable was "a Bradshaw", no matter by which railway company it had been issued, or whether Bradshaw had been responsible for its production or not.  The eight-page edition of 1841 had grown to 32 pages by 1845 and to 946 pages by 1898 and now included maps, illustrations and descriptions of the main features and historic buildings of the towns served by the railways.[8] In April 1845, the issue number jumped from 40 to 141:[6] the publisher claimed this was an innocent mistake, although it has been speculated as a commercial ploy, where more advertising revenue could be generated by making it look longer-established than it really was. Whatever the reason for the change, the numbering continued from 141. When in 1865, Punch praised Bradshaw's publications, it stated that "seldom has the gigantic intellect of man been employed upon a work of greater utility." At last, some order had been imposed on the chaos that had been created by some 150 rail companies whose tracks criss-crossed the country and whose largely uncoordinated network was rapidly expanding. Bradshaw minutely recorded all changes and became the standard manual for rail travel well into the 20th century. By 1918 Bradshaw's guide had risen in price to two shillings and by 1937 to half a crown (equivalent to £10 in 2023).[9] Later history Bradshaw's timetables became less necessary from 1923, when more than 100 surviving companies were "grouped" into the Big Four.[3] This change reduced dramatically the range and number of individual timetables produced by the companies themselves. They now published a much smaller number of substantial compilations which between them covered the country. Between 1923 and 1939, three of the Big Four transferred their timetable production to Bradshaw's publisher Henry Blacklock & Co., and most of the official company timetables therefore became reprints of the relevant pages from Bradshaw. Only the Great Western Railway retained its own format. Between the two world wars, the verb 'to Bradshaw' was a derogatory term used in the Royal Air Force to refer to pilots who could not navigate well, perhaps related to a perceived lack of ability shown by those who navigated by following railway lines. When the railways were nationalised in 1948, five of the six British Railways Regions followed the companies' example by using Blacklock to produce their timetable books, but production was eventually moved to other publishers. This change must have reduced Blacklock's revenue substantially. Parts of Bradshaw's guide began to be reset in the newer British Railways style from 1955, but modernisation of the whole volume was never completed. By 1961 Bradshaw cost 12s 6d (62½p), and a complete set of BR Regional timetables could be bought for 6s (30p). The conclusion was inevitable, and the last edition, No. 1521, was dated May 1961. The Railway Magazine of that month printed a valedictory article by Charles E. Lee. Reprints of various Bradshaw's guides have been produced. References in literature19th-century and early 20th-century novelists make frequent references to a character's "Bradshaw". Dickens refers to it in his short stories "The Portrait-Painter's Story" (1861) and "Mrs Lirriper's Lodgings" (1863),[10] so does Trollope in “He knew he was right” (1869). In Jules Verne's Around the World in 80 Days, Phileas Fogg carries a Bradshaw. In W. Somerset Maugham's "The Book Bag" the narrator states "I would sooner read the catalogue of the Army and Navy Stores or Bradshaw's Guide than nothing at all, and indeed have spent many delightful hours over both these works" Crime writers were fascinated with trains and timetables, especially as a new source of alibis. Examples are Ronald Knox's The Footsteps at the Lock (1928) and novels by Freeman Wills Crofts. One mention is by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in the Sherlock Holmes story The Valley of Fear: "the vocabulary of Bradshaw is nervous and terse, but limited." Other references include another Sherlock Holmes story, "The Adventure of the Copper Beeches"; Lewis Carroll's long poem Phantasmagoria; and Bram Stoker's Dracula, which makes note of Count Dracula reading an "English Bradshaw's Guide" as part of his planning for his voyage to England. In the 1866 comic opera Cox and Box, the following exchange takes place:

There is also a reference in Death in the Clouds (1935) by Agatha Christie: "Mr Clancy, writer of detective stories ... extracted a Continental Bradshaw from his raincoat pocket ... to work out a complicated alibi." Bradshaw is also mentioned in her novel The Secret Adversary. In Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca (1938), the second Mrs de Winter observes that "Some people have a vice of reading Bradshaws. They plan innumerable journeys across country for the fun of linking up impossible connections." (chapter 2). Another reference is in an aside in The Riddle of the Sands (1903) by Erskine Childers: "... an extraordinary book, Bradshaw, turned to from habit, even when least wanted, as men fondle guns and rods in the close season." In G. K. Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday, the protagonist Gabriel Syme praises Bradshaw as a poet of order: "No, take your books of mere poetry and prose; let me read a time table, with tears of pride. Take your Byron, who commemorates the defeats of man; give me Bradshaw, who commemorates his victories. Give me Bradshaw, I say!" In Max Beerbohm's Zuleika Dobson (1911), a satirical fantasy of Oxford undergraduates, a Bradshaw is listed as one of the two books in the "library" of the irresistible Zuleika. Anthony Trollope refers to Bradshaw's in Barchester Towers and The Warden. Bradshaw is mentioned in modern novels with a period setting, and in Philip Pullman's The Shadow in the North (Sally Lockhart Quartet). In Jerome K. Jerome's 1891 novel Diary of a Pilgrimage, contains an aside called A Faithful Bradshaw. This section describes a comical incident where the author always gets misled by referring to outdated guides. In the Terry Pratchett Discworld novel “Raising Steam,” Moist Von Lipwig meets a Mrs. Georgina Bradshaw who subsequently begins writing guides to rail destinations for the Ankh-Morpork and Sto Lat Hygienic Railway. Bradshaw's Continental Railway GuideIn June 1847 the first number of Bradshaw's Continental Railway Guide was issued, giving the timetables of the Continental railways. It grew to over 1,000 pages, including timetables, guidebook and hotel directory. It was discontinued in 1914 at the outbreak of the First World War. Briefly resurrected in the interwar years, it saw its final edition in 1939. The 1913 edition was republished in September 2012.[12] A travel documentary series named Great Continental Railway Journeys has been made based on the 1913 edition. Bradshaw's and other printed timetables todayIn December 2007, Middleton Press[13] took advantage of Network Rail's willingness to grant third-party publishers the right to print paper versions of the National Rail timetable. Network Rail had discontinued official hard copies in favour of PDF editions, which could be downloaded free of charge. As a tribute to Bradshaw, Middleton Press named its timetables the Bradshaw-Mitchell's Rail Times. A competing edition reproduced from Network Rail's artwork, is published by TSO,[14] This is a same-size reproduction of the Network Rail artwork, although the size is only about 70% in the Middleton Press versions to reduce the page count. A third publisher, UK Rail Timetables,[15] The main timetable for Indian Railways is still known as the Newman Indian Bradshaw.[16] List of Bradshaw's by geographic coverageBritish IslesTimetables

Guidebooks

Australia

France

Germany, Austria and Belgium

India

Italy

New Zealand

Syria

Turkey

International

List of Bradshaw's by date of publication1830s–1840s

1850s–1860s

1870s–1880s

1890s–1900s

Notes

References

Sources

Further readingWikimedia Commons has media related to Bradshaw's Guide. Wikisource has original text related to this article:

|