|

Bottom of the pyramid

The bottom of the pyramid, bottom of the wealth pyramid, bottom of the income pyramid or the base of the pyramid is the largest, but poorest socio-economic group. In global terms, this is the 2.7 billion people who live on less than $2.50 a day.[1][2] Management scholar CK Prahalad popularised the idea of this demographic as a profitable consumer base in his 2004 book The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, written alongside Stuart Hart.[3] HistoryU.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt used the term in his April 7, 1932 radio address, The Forgotten Man, in which he said,

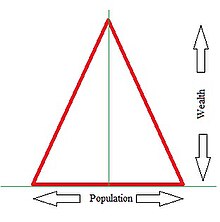

The more current usage refers to the billions of people living on less than $2.50 per day, the definition proposed in 1998 by C.K. Prahalad and Stuart L. Hart. It was subsequently expanded upon by both in their books: The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid by Prahalad in 2004[4] and Capitalism at the Crossroads by Hart in 2005.[5] Prahalad proposes that businesses, governments, and donor agencies stop thinking of the poor as victims and instead start seeing them as resilient and creative entrepreneurs as well as value-demanding consumers.[6] He proposes that there are tremendous benefits to multi-national companies who choose to serve these markets in ways responsive to their needs. After all the poor of today are the middle class of tomorrow. There are also poverty reducing benefits if multi-nationals work with civil society organizations and local governments to create new local business models. However, there is some debate over Prahalad's proposition. Aneel Karnani, also of the Ross School at the University of Michigan, argued in a 2007 paper that there is no fortune at the bottom of the pyramid and that for most multinational companies the market is really very small.[7] Karnani also suggests that the only way to alleviate poverty is to focus on the poor as producers, rather than as a market of consumers. Prahalad later provided a multi-page response to Karnani's article. Additional critiques of Prahalad's proposition have been gathered in "Advancing the 'Base of the Pyramid' Debate". Meanwhile, Hart and his colleague Erik Simanis at Cornell University's Center for Sustainable Global Enterprise advance another approach, one that focuses on the poor as business partners and innovators, rather than just as potential producers or consumers. Hart and Simanis have led the development of the Base of the Pyramid Protocol, an entrepreneurial process that guides companies in developing business partnerships with income-poor communities in order to "co-create businesses and markets that mutually benefit the companies and the communities". This process has been adopted by the SC Johnson Company[8] and the Solae Company (a subsidiary of DuPont).[9] Furthermore, Ted London at the William Davidson Institute at the University of Michigan focuses on the poverty alleviation implications of Base of the Pyramid ventures. He has created a BoP teaching module designed for integration into a wide variety of courses common at business schools that explain the current BoP thinking. He has identified the BoP Perspective as a unique market-based approach to poverty alleviation. London has also developed the BoP Impact Assessment Framework, a tool that provides a holistic and robust guide for BoP ventures to assess and enhance their poverty alleviation impacts. This framework, along with other tools and approaches, is outlined in London's Base of the Pyramid Promise and has been implemented by companies, non-profits, and development agencies in Latin America, Asia, and Africa.[10] Another recent focus of interest lies on the impact of successful BoP-approaches on sustainable development. Some of the most significant obstacles encountered when integrating sustainable development at the BoP are the limits to growth that restrict the extended development of the poor, especially when applying a resource-intensive Western way of living. Nevertheless, from a normative ethical perspective poverty alleviation is an integral part of sustainable development according to the notion of intragenerational justice (i.e. within the living generation) in the Brundtland Commission's definition. Ongoing research addresses these aspects and widens the BoP approach also by integrating it into corporate social responsibility thinking.[citation needed] What is the actual shape of the wealth pyramid? The pyramid is a graphical depiction of inverse relationship between two variables as one increases the other decreases. We find that the percent of world wealth and the percent of world population controlling it are related with each other in an inverse relation. If we plot the world wealth in percent terms along the vertical axis of a graph and the corresponding percent population having control on it on the horizontal axis of a graph and add the mirror image of this graph on the left side of the vertical axis we get a wealth pyramid and can see that as we move to higher and higher wealth brackets we find that fewer and fewer people have access to it, thus the figure has a wide bottom and a lean top similar to the pyramids of Egypt. It has been reported that the gap between the ToP and BoP is widening over time in such a way that only 1% of the world population controls 50% of the wealth today, and the other 99% is having access to the remaining 50% only.[12][13] On the basis of this report the wealth pyramid would look like the one shown in the illustration. How low is the bottom?The standards and benchmarks developed – for example less than $2.5 a day – always tell us about the upper limit of what we call the BoP, and not actually about its base or bottom. The fact is that the bottom or the base is much much lower. Even going by the official definition, for example in India the Rangarajan Committee after re-examining the issue of poverty defined the poverty line in 2011-12 at INR 47.00 ($0.69) per capita per day for urban areas and INR 32.00 ($0.47) per capita per day in rural areas (June 2016 conversion rate),[14] obviously much less than the $2.5 per day benchmark. This again is the upper layer of the poor as defined by the Rangarajan Committee. Where is the actual bottom? and how low? This can perhaps only be visualised by observing the slums right in the hearts of the cities in the developing countries. Good business sense and the BoP marketsKash Rangan, John Quelch, and other faculty members at the Global Poverty Project at Harvard Business School "believe that in pursuing its own self-interest in opening and expanding the BoP market, business can make a profit while serving the poorest of consumers and contributing to development."[15] According to Rangan, "For business, the bulk of emerging markets worldwide is at the bottom of the pyramid so it makes good business sense – not a sense of do-gooding – to go after it."[15] But in the view of Friedman "the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits only, thus, it needs to be examined whether business in BoP markets is capable of achieving the dual objective of making a profit while serving the poorest of consumers and contributing to development?"[16] Erik Simanis has reported that the model has a fatal flaw. According to Simanis, "Despite achieving healthy penetration rates of 5% to 10% in four test markets, for instance, Procter & Gamble couldn’t generate a competitive return on its Pur water-purification powder after launching the product on a large scale in 2001...DuPont ran into similar problems with a venture piloted from 2006 to 2008 in Andhra Pradesh, India, by its subsidiary Solae, a global manufacturer of soy protein ... Because the high costs of doing business among the very poor demand a high contribution per transaction, companies must embrace the reality that high margins and price points aren't just a top-of-the-pyramid phenomenon; they’re also a necessity for ensuring sustainable businesses at the bottom of the pyramid."[17] Marc Gunther states that, "The bottom-of-the-pyramid (BOP) market leader, arguably, is Unilever ... Its signature BOP product is Pureit, a countertop water-purification system sold in India, Africa and Latin America. It's saving lives, but it's not making money for shareholders."[18] Several consulting companies have modeled the profitability of accessing the bottom of pyramid by utilizing economies of scale.[19] Examples of BoP businessMicrocreditOne example of "bottom of the pyramid" is the growing microcredit market in South Asia, particularly in Bangladesh. With technology being steadily cheaper and more ubiquitous, it is becoming economically efficient to "lend tiny amounts of money to people with even tinier assets". An Indian banking report argues that the microfinance network (called "Sa-Dhan" in India) "helps the poor" and "allows banks to 'increase their business'".[20] However, formal lenders must avoid the phenomenon of informal intermediation: Some entrepreneurial borrowers become informal intermediaries between microfinance initiatives and poorer micro-entrepreneurs. Those who more easily qualify for microfinance split loans into smaller credit to even poorer borrowers. Informal intermediation ranges from casual intermediaries at the good or benign end of the spectrum to 'loan sharks' at the professional and sometimes criminal end of the spectrum.[21] Market-specific productsOne of many examples of products that are designed with needs of the very poor in mind is that of a shampoo that works best with cold water and is sold in small packets to reduce barriers of upfront costs for the poor. Such a product is marketed by Hindustan Unilever. InnovationThere is a traditional view that BOP consumers do not want to adopt innovation easily. However, C. K. Prahalad (2005) claimed against this traditional view, positing that the BOP market is very eager to adopt innovations. For instance, BOP consumers are using PC kiosks, Mobile phone, Mobile banking etc. Relative advantage and Complexity attributes of an innovation suggested by Everett Rogers (2004) significantly influence the adoption of an innovation in the Bottom of pyramid market (Rahman, Hasan, and Floyd, 2013). Therefore, innovation developed for this market should focus on these two attributes (Relative advantage and Complexity). Venture capitalWhereas Prahalad originally focused on corporations for developing BoP products and entering BoP markets, it is believed by many that Small to Medium Enterprises (SME) might even play a bigger role. For Limited Partners (LPs), this offers an opportunity to enter new venture capital markets. Although several social venture funds are already active, true Venture Capital (VC) funds are now emerging. BrandThere is a traditional view that BOP consumers are not brand conscious (Prahalad, 2005). However, C. K. Prahalad (2005) claimed against this traditional view, positing that the BOP market is brand conscious. For instance, brand influences the new product adoption in the bottom of pyramid market (Rahman, Hasan, and Floyd, 2013). Rahman et al. (2013) mentioned that brand may positively influence the relative advantage of an innovation and it leads to adoption of innovation in the BOP. In point of traditional view BOP market, people were not aware about brand concept. Sopan Kumbhar (2013) Business and community partnershipsAs Fortune reported on November 15, 2006, since 2005 the SC Johnson Company has been partnering with youth groups in the Kibera slum of Nairobi, Kenya. Together SC Johnson and the groups have created a community-based waste management and cleaning company, providing home-cleaning, insect treatment, and waste disposal services for residents of the slum. SC Johnson's project was the first implementation of the "Base of the Pyramid Protocol". ConferencesThere have been a number of academic and professional conferences focused on the BoP. A sample of these conferences are listed below:

Footnotes

Sources

Further reading

External links |