|

Borneo peat swamp forests

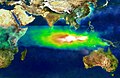

The Borneo peat swamp forests ecoregion, within the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome, are on the island of Borneo, which is divided between Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia. Location and descriptionPeat swamp forests occur where waterlogged soils prevent dead leaves and wood from fully decomposing, which over time creates thick layer of acidic peat. The peat swamp forests on Borneo occur in the Indonesian state of Kalimantan, the Malaysian state of Sarawak and in the Belait District of Brunei on coastal lowlands, built up behind the brackish mangrove forests and bounded by the Borneo lowland rain forests on better-drained soils. There are also areas of inland river-fed peat forest at higher elevations in central Kalimantan around the Mahakam Lakes and Lake Sentarum on the Kapuas River.[2] Borneo has a tropical monsoon climate. Recent historyOver the past decade, the government of Indonesia has drained over 1 million hectares of the Borneo peat swamp forests for conversion to agricultural land under the Mega Rice Project (MRP). Between 1996 and 1998, more than 4,000 km of drainage and irrigation channels were dug, and deforestation accelerated in part through legal and illegal logging and in part through burning. The water channels, and the roads and railways built for legal forestry, opened up the region to illegal forestry. In the MRP area, forest cover dropped from 64.8% in 1991 to 45.7% in 2000, and clearance has continued since then. It appears that almost all the marketable trees have now been removed from the areas covered by the MRP. What happened was not what had been expected: the channels drained the peat forests rather than irrigating them. Where the forests had often flooded up to 2m deep in the rainy season, now their surface is dry at all times of the year. The Indonesian government has now abandoned the MRP. FiresFires were used in an attempt to create agricultural lands, including large palm tree plantations to supply palm oil. The dried-out peat ignites easily and also burns underground, travelling unseen beneath the surface to break out in unexpected locations. Therefore, after drainage, fires ravaged the area, destroying remaining forest and large numbers of birds, animals, reptiles and other wildlife along with new agriculture, even damaging nature reserves such as Muara Kaman[3] and filling the air above Borneo and beyond with dense smoke and haze and releasing enormous quantities of CO2 into the atmosphere. The destruction had a major negative impact on the livelihoods of people in the area. It caused major smog-related health problems amongst half a million people, who suffered from respiratory problems.[4] The dry years of 1997-8 and 2002-3 (see El Niño) in particular saw huge fires in the drained and drying-out peat swamp forests. A study for the European Space Agency found that the peat swamp forests are a significant carbon sink for the planet, and that the fires of 1997-8 may have released up to 2.5 billion tonnes, and the 2002-3 fires between 200 million to 1 billion tonnes, of carbon into the atmosphere.[5] Using satellite images from before and after the 1997 fires, scientists calculated (Page et al, 2002) that of the 790,000 hectares (2,000,000 acres) that had burned 91.5% was peatland 730,000 hectares (1,800,000 acres). Using ground measurements of the burn depth of peat, they estimated that 0.19–0.23 gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon were released into the atmosphere through peat combustion, with a further 0.05 Gt released from burning of the overlying vegetation. Extrapolating these estimates to Indonesia as a whole, they estimated that between 0.81 and 2.57 Gt of carbon were released to the atmosphere in 1997 as a result of burning peat and vegetation in Indonesia. This is equivalent to 13–40% of the mean annual global carbon emissions from fossil fuels, and contributed greatly to the largest annual increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration detected since records began in 1957. Indonesia is currently the world's third largest carbon emitter, to a large extent due to the destruction of its ancient peat swamp forests (Pearce 2007).

Ecology About 62% of the world's tropical peat lands occur in the Indo-Malayan region (80% in Indonesia, 11% in Malaysia, 6% in Papua New Guinea, with small pockets and remnants in Brunei, Vietnam, the Philippines and Thailand).[6][7] They are unusual ecosystems, with trees up to 70 m high - vastly different from the peat lands of the north temperate and boreal zones (which are dominated by Sphagnum mosses, grasses, sedges and shrubs). The spongy, unstable, waterlogged, anaerobic beds of peat can be up to 20 m deep with low pH (pH 2.9 – 4) and low nutrients, and the forest floor is seasonally flooded.[8] The water is stained dark brown by the tannins that leach from the fallen leaves and peat – hence the name 'blackwater swamps'. During the dry season, the peat remains waterlogged and pools remain among the trees. Despite the extreme conditions the Borneo peat swamp forests have as many as 927 species of flowering plants and ferns recorded[9] (In comparison, a biodiversity study in the Pekan peat swamp forest in Peninsular Malaysia reported 260 plant species).[10] Patterns of forest type can be seen in circles from the centre of the swamps to their outer fringes which are made up of most of the tree families recorded in lowland dipterocarp forests although many species are only found here [citation needed]. Many trees have buttresses and stilt roots for support in the unstable substrate, and pneumatophores and hoop roots and knee roots to facilitate gas exchange. The trees have thick, root mats in the upper 50 cm of the peat to enable oxygen and nutrient uptake.  The lowland peat swamps of Borneo are mostly geologically recent (<5,000 years old), low-lying coastal formations above marine muds and sands [11][7] but some of the lakeside peat forests of Kalimantan are up to 11,000 years old. One reason for the low nutrient conditions is that streams and rivers do not flow into these forests (if they did, nutrient rich freshwater swamps would result), water only flows out of them, so the only input of nutrients is from rainfall, marine aerosols and dust. In order to cope with the lack of nutrients, the plants invest heavily in defences against herbivores such as chemical (toxic secondary compounds) and physical defences (tough leathery leaves, spines and thorns). It is these defences that prevent the leaves from decaying and so they build up as peat. Although the cellular contents quickly leach out of the leaves when they fall, the physical structure is resistant to both bacterial and fungal decomposition and so remains intact, slowly breaking down to form peat (Yule and Gomez 2008). This is in stark contrast to the lowland dipterocarp forests where leaf decomposition is extremely rapid, resulting in very fast nutrient cycling on the forest floor. If non-endemic leaf species are placed in the peat swamp forests, they break down quite quickly, but even after one year submerged in the swamp, endemic species remain virtually unchanged (Yule and Gomez 2008). The only nutrients available for the trees are thus the ones that leach from the leaves when they fall, and these nutrients are rapidly absorbed by the thick root mat. It was previously assumed that the low pH and anaerobic conditions of the tropical peat swamps meant that bacteria and fungi could not survive, but recent studies have shown diverse and abundant communities (albeit not nearly as diverse as dry land tropical rainforests, or freshwater swamps) (Voglmayr and Yule 2006; Jackson, Liew and Yule 2008). FaunaThese forests are home to wildlife including gibbons, orangutans, and crocodiles. In particular the riverbanks of the swamps are important habitats for the crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis) and the silvery lutung (Presbytis cristata) and are the main habitat of Borneo's unique and endangered proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) which can swim well in the rivers, and the Borneo roundleaf bat (Hipposideros doriae). There are two birds endemic to the peat forests, the Javan white-eye (Zosterops flavus) and the hook-billed bulbul (Setornis criniger) while more than 200 species of birds have been recorded in Tanjung Puting National Park in Kalimantan. Rivers of the peat swamps are home to the rare arowana fish (Scleropages formosus), otters, waterbirds, false gharials and crocodiles. Another small species of fish are the Parosphromenus which are also extremely endangered. The parosphromenus species are small fish of extreme beauty. ConservationAttempts at conservation have been minimal in comparison to recent devastation while commercial logging of peat swamp forest in Sarawak is ongoing and planned to intensify in Brunei. One plan by the environmental NGO Borneo Orangutan Survival is to preserve the peat swamp forest of Mawas using a combination of carbon finance and debt-for-nature-swap. Peatland conservation and rehabilitation are more efficient undertakings than reducing deforestation (in terms of claiming carbon credits through REDD initiatives) due to the much larger reduced emissions achievable per unit area and the much lower opportunity costs involved.[12] 9.317% of the ecoregion is within protected areas, the largest of which are Tanjung Puting and Sabangau National Parks. They also include Belait Peat Swamp (Ulu Mendaram Conservation Forest Reserve) and portions of Rajang Mangrove, Lambir Hills, Loagan Bunut, Bruit, Maludam, Gunung Palung, Danau Sentarum, Ulu Sebuyau, Sedilu, Kuching Wetland, and Gunung Lesong national parks.[13] See also

References

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||