|

Blackrock (film)

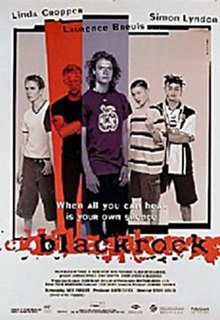

Blackrock is a 1997 Australian teen drama thriller film produced by David Elfick and Catherine Knapman, directed by Steven Vidler with the screenplay by Nick Enright. Marking Vidler's directorial debut, the film was adapted from the play of the same name, also written by Enright, which was inspired by the murder of Leigh Leigh. The film stars Laurence Breuls, Simon Lyndon and Linda Cropper, and also features the first credited film performance of Heath Ledger. The film follows Jared (Breuls), a young surfer who witnesses his friends raping a girl. When she is found murdered the next day, Jared is torn between revealing what he saw and protecting his friends. Leigh's family opposed the fictionalisation of her murder, though protests against the film were abandoned after it received financial backing from the New South Wales Film and Television Office. Blackrock was filmed over a period of two weeks at locations including Stockton, where Leigh was murdered, a decision that was opposed by local residents who said that memories of the murder were still fresh. While the film was never marketed as being based on a true story, numerous comparisons between the murder and the film were made, and many viewers believed it to be a factual account of the murder. The film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, and was also shown at the Boston Film Festival, though it failed to find an American theatrical distributor. It was nominated for five AACTA Awards, including Best Film, and won the Feature Film – Adaptation award as well as the Major Award at the 1997 AWGIE Awards. It received generally positive reviews in Australia, where it grossed $1.1 million at the box office. Outside Australia, where audiences were less familiar with Leigh's murder, critical reception of the film was mixed. PlotBlackrock is an Australian beachside working-class suburb[a] in which surfing is popular among youths like Jared. His first serious girlfriend is Rachel, who comes from a much wealthier part of the city. One day, Ricko, a surfer popular among the local youths, returns from an eleven-month trip. Jared's mother, attempts to tell Jared that she has been diagnosed with breast cancer, but Jared insists on talking to her later as he is busy arranging a "welcome home" party for Ricko at the local surf club. Rachel's father, a photographer who takes provocative images of women, forbids her from attending the party but allows her older brother, Toby, to attend. While driving to the party, Toby sees Tracy, Cherie and two other girls and gives them a ride. Jared flirts with Tracy at the party and then gets into a fight with Toby. Ricko comes to Jared's defence, but Jared breaks up the fight after Ricko hits Toby several times. Tracy comes to comfort Toby, and Jared leaves the party to head to the beach alone. Jared sees Toby having consensual sex with Tracy on the beach. He then witnesses three of his male friends interrupting the couple and raping Tracy. Tracy calls out for help, but Jared, who is visibly disturbed by what he is witnessing, does not intervene. Toby and the other three boys, who never noticed Jared was watching, flee the area. Jared also runs away and leaves Tracy alone and distressed. Later that night Rachel, who has sneaked out of home to attend the party, finds Tracy's beaten corpse on the beach. Jared initially tells the police nothing of what he saw. He is torn between the need to tell the truth and the desire to protect his friends. His anger leads to the breakdown of his relationships with both Rachel and Diane. Despite Jared's silence, police arrest Toby and the three other boys within a few days. Jared decides to tell the police what he saw, as he believes Toby and the other boys will be charged with Tracy's murder. However, on his way into the police station he is confronted by Ricko, who confesses to Jared that he killed Tracy, but claims it was an accident. She hit her head on a rock when he attempted to have sex with her. He has already told police that he was with Jared all night and asks Jared to confirm his alibi in the name of mateship. Diane, who still has not been able to tell Jared that she has cancer because of his behaviour, goes in to have surgery. Jared tells the police that he was with Ricko. When he tries to suggest Tracy's death may have been an accident, the police show him the photos of Tracy's battered body. Jared aggressively confronts Ricko at the beach, and Ricko confesses that Tracy's death was not an accident. He had found her walking on the beach after the rape, and she asked him to take her home. He agreed but wanted to have sex with her first. She tried to fight him off and bit him in the process, which enraged him enough to beat her to death. As Ricko finishes his confession, the police arrive, and he realises that Jared has turned him in. He attempts to escape, but the police give chase and corner him on a cliff. Rather than go to jail and ignoring Jared's screams of protest, he jumps to his death. In the weeks that follow, Jared's life collapses. Despite learning of Diane's illness, he moves out of her house and chooses instead to be homeless. Jared returns home one day to collect his belongings; after arguing with Diane, he confesses that he witnessed Tracy's rape and could have saved her life if he had intervened or helped her afterwards. Later that day, Jared joins Diane and Cherie in cleaning graffiti from Tracy's grave. Cast

ThemesWriting in the journal Antipodes, academics Felicity Holland and Jane O'Sullivan credit the film with exploring the themes of Australian masculinity, mateship, violence and sexuality. The film's portrayal of a rape and murder at a teenage party suggests that serious crime can arise from drinking and fun simply getting out of hand. The violence, they say, erupts from extreme larikkinism rather than the archetypal psychopathy seen in other films featuring violence towards women. The film's critique of criminal masculinity undermines the status of previously celebrated masculine lawbreakers in Australian history and cinema, such as Ned Kelly and Mick Dundee. The authors believe that the focus on masculinity leaves the female victim largely out of the film; they consider the "near erasure" of Tracy to be a troubling aspect; the film instead focuses on portraying the males as victims of their class, masculinity and mateship.[5] Director Steven Vidler said the film was not about a rape, rather it was "about the culture that allowed it to happen." Vidler defended the choice to give the rape victim a minor role, stating, "It was important to show that this could have happened to anyone. We didn't want to give away too much about the victim so we could maintain that suspense."[6] Producer David Elfick said that the film was about contemporary Australia; about "kids who have all their life to enjoy, then a deadly mixture of drugs, alcohol, sexual tension, and desire add up to a tragedy."[2] ProductionTheatrical originsBrian Joyce, the director of Newcastle's Freewheels Theatre in Education, approached playwright Nick Enright, encouraging him to create a play that explored themes around the 1989 rape and murder of Leigh Leigh in Stockton, a beach area of Newcastle.[7][8] Leigh's family objected to the fictionalisation of her murder.[9] Titled A Property of the Clan, the 45-minute play premiered at the Freewheels Theatre in 1992 and was performed at the National Institute of Dramatic Art in 1993.[10] The play was shown at various high-schools in the Newcastle area and, following its positive reception, was shown nationally at high schools across the country over a period of eighteen months.[11] In 1994, the Sydney Theatre Company commissioned Enright to develop the play into a feature-length production.[9] The resulting play was titled Blackrock. Blackrock retained the original four characters from A Property of the Clan,[11] and added nine others; it was considered a more fictionalised version of Leigh's murder.[9] The narrative and emphasis were reshaped for an adult audience rather than for a specifically educational environment.[12] Film adaptationWhile the revisions to the play Blackrock were still being finalised, Enright started working with first-time director Steven Vidler to direct a film version,[13] which would also be titled Blackrock.[9] By December 1995, Vidler was working with Enright as an unofficial script editor, although they were having trouble finding financing for the film. Vidler said he considered directing the film Blackrock after having watched and been moved by the theatrical version, saying the play was "absolutely what it was like [for him] growing up in the Western Suburbs ... It's about keeping bonded with your mates. Nothing else matters ... It's about the unbelievable lengths boys will go to keep those bonds solid."[14] Leigh's mother Robyn campaigned to have production of the film halted, but her attempts failed after the film received government financial backing[15] from the New South Wales Film and Television Office.[16] Blackrock was filmed over a period of two weeks with a cast and crew of about 70. A call for extras received an enthusiastic response by many teenagers in the Newcastle area. Filming locations included Stockton, Maroubra Beach, Caves Beach, and NESCA House.[2] Notable Stockton landmarks seen in the film include the Stockton Ferry[15] and Stockton Bridge.[2]  The community of Stockton opposed filming in the area, as memories of Leigh's murder were still fresh and the details of the script were "too close for comfort".[9] When filmmakers arrived in Stockton in late August 1996,[17] locations that had previously been reserved were suddenly no longer available. The local media treated them with hostility.[9] Former Newcastle deputy mayor and Stockton resident Frank Rigby criticised the film during production, saying "I would just love it to go away and so would everybody else."[2] Brian Joyce was also critical of the decision to film in the area, saying the filmmakers had to acknowledge the choice they had made in doing so.[17][2] The situation was exacerbated by the filmmakers' denial that the film was specifically about Leigh, despite their choice of Stockton for filming.[18] During production in September 1996, Elfick told The Newcastle Herald that he was "getting a bit bored" of people mentioning Leigh's murder. While acknowledging that the comments were understandable, Elfick concluded, "Unfortunately, that event happens all over Australia. We wanted to take the events of that murder and many other murders". He was also quoted in The Sydney Morning Herald as saying, "The movie is bigger than the Leigh Leigh thing".[3] Elfick hoped that people viewing the film would see it as a positive way of looking at the circumstances that led to Leigh's death,[2] and that it would make people think and maybe stop something like that happening to someone in the future.[19] Leigh's family were vehemently opposed to the film, saying that the filmmakers were "feasting on an unfortunate situation",[9] insensitively trivialising and exploiting her death, and portraying her negatively while doing so.[17] One of Leigh's aunts wrote to The Newcastle Herald later that month, saying "David Elfick doesn't seem to mind free publicity even if it comes from the tragic and brutal assault, rape, and murder of a fourteen-year-old virgin, not as he called it: 'the Leigh Leigh thing which happens all over Australia.'"[20] Enright said that while Leigh's murder served as the inspiration, the completed film is about the way a small town reacts when one of its own members murders another.[2] CastingSandy George from Australian Screen Online said that Vidler's long career as an actor helped him "draw the terrific performances" from the film's young actors.[21] 17-year-old Laurence Breuls was literally the first person to audition for the role of Jared. Hundred of others auditioned though Breuls remained the favourite choice.[22] Vidler chose Simon Lyndon, who played the role of Jared in the original stage production of Blackrock, for the role of Ricko, stating that Lyndon had the looks, charisma, and complexity to play the role.[6] Rebecca Smart, who also portrayed Cherie in the original stage production,[23] was the only person to reprise their role from the play. Blackrock is often considered to be Heath Ledger's debut film,[24] but he had an uncredited minor role in the 1991 TV film Clowning Around.[25] While Ledger's role in Blackrock is small, it is credited with garnering him attention in Australia, leading to more prominent acting roles.[26] 15-year-old Bojana Novakovic was given the role of Tracy partly because she was a competitive gymnast and was considered mentally and physically strong enough to film the rape scene. Vidler discussed the role with her parents before filming commenced, who despite initial reservations, eventually gave permission for her to film the scene. Novakovic said the experience was traumatic and she began to tremble uncontrollably once the shoot ended, though recovered shortly afterwards, concluding, "In a way, I feel lucky to have had such a role at the beginning of my career. I don't think I'll ever be scared by an emotional scene again." The boys involved in the scene showed up at her door the following day and gave her a bunch of flowers and a T-shirt that said "shit happens".[6] Vidler said he found the performance so powerful that when he first watched the rushes of the scene alone, he burst into tears.[6] Soundtrack

The soundtrack to the film was released on 28 April 1997 on Mercury Records Australia. Vidler said a lot of time was spent sifting through hundred of CDs "trying to find stuff that was not only appropriate for the film but would also be appealing to the audiences and hopefully, you know, would be released around the same time as the film, which isn't as easy as it sounds!"[22] Jonathan Lewis from AllMusic gave the album four and a half out of five stars, concluding that it was "A fine collection of songs that, given the diversity of artists featured, is surprisingly cohesive as an album."[27] Track listing

ReleaseThe film debuted at the Sundance Film Festival on 24 January 1997. It was also shown at the Boston Film Festival on 7 September 1997.[28] The version of the film shown outside Australia was around 100 minutes long; upon reviewing this version the Australian Classification Board gave it an 'R' rating, stating the rape scene was "too harrowing and confronting" for an MA15+ rating. Vidler subsequently cut about 10 minutes of footage out of the film so it could receive an MA15+ rating and reach its target audience of 15- to 18-year-olds.[6] Blackrock opened in 77 cinemas in Australia on 1 May 1997 grossing $401,599 for the week, placing seventh at the Australian box office.[6][29] It went on to gross $1,136,983 at the Australian box office.[4] ReceptionIn anticipation of the film's debut at Sundance, John Brodie from Variety said the film could be the "thunder from Down Under the way Shine was last year."[30] Having watched the film at Sundance, David Rooney from Variety praised several of the actors' performances and said the film "should score with kids the protagonists' age, but its soap-opera-style plotting and overwritten dialogue will limit wider acceptance".[31] Premiere also gave a negative review of the film's debut,[9] commenting that audiences had been expecting to see another Shine, though left the screening disappointed.[3] Elfick acknowledged that the initial screening of Blackrock at Sundance was less well received, which he blamed on sound problems. He stated that the issue was rectified for the second and third screenings, which were much more successful.[3] Diane Carmen of The Denver Post gave the film a positive review of the film, which she said left audiences at Sundance "reeling with its intensity", concluding it was "almost guaranteed to find a distributor in the U.S",[32] though in the event the film never received American distribution.[9] Having viewed the film at the Boston Film Festival, Chris Wright from The Phoenix concluded, "Even with its slightly over-the-top dénouement, Blackrock is a believable, touching teen drama. It's also a gripping thriller".[33] R.S. Murthi from the Malaysian newspaper New Straits Times gave the film two out of five stars, concluding it is "an unflattering but somewhat forced look at the wild side of teen life that at times seems dangerously tolerant of unrestrained teen behaviour."[34] Associate professor Donna Lee Brien of Central Queensland University said that when shown outside Australia, the film lacks the "poignant and powerful narrative support of Leigh's tragedy" and was deemed by critics to be "shallow and clichéd".[9] Australian novelist and critic Robert Drewe gave a positive review, praising the performance of Breuls, the cinematography by Martin McGrath, and director Steven Vidler's choice of such a controversial subject for a first film. Upon noting that the filmmakers deliberately insisted that their characters be portrayed as different from the actual people involved in the Leigh Leigh murder as possible, Drewe said the film is "asking a lot of Australian audiences to expunge reality from their memories", though he concluded that the film should be "compulsory viewing for all Australian teenagers."[13] Rob Lowing from The Sun-Herald noted that the film belonged to a slew of Australasian films that focused on middle class life and ultimately gave the film 3½ stars out of 4, stating, "if you went to see Romper Stomper, Metal Skin, Idiot Box or Once Were Warriors, this gritty, punchy social drama ably fits into that class."[35] In her book Who Killed Leigh Leigh?, Kerry Carrington, a criminologist and prominent researcher of Leigh's murder, had both criticism and praise for the film. She praised it for dispelling "the myth" that sexual violence is confined to one social class, for illustrating how boys model their sexual conduct on their fathers' treatment of women, and how the culture of sex segregation in workplaces can carry over into the public life of a town, exacerbating sexist beliefs and behaviours. She criticised the film, however, for the "strong impression" it makes that ineffectual mothers are part of the underlying problem and for several differences between Leigh's murder and the film that she considered to be disrespectful to Leigh's memory, in particular the film's "Hollywood ending".[36] Donna Lee Brien stated that just as the filmmakers attempted to distance themselves from Leigh's murder, the city of Newcastle attempted to distance itself from Blackrock. A 1999 feature in The Sydney Morning Herald discussing cinematic production in Newcastle mentioned everything from Mel Gibson's 1977 debut film Summer City to a short film festival that year, but made no mention of Blackrock.[37] Brien theorised that some of the condemnation the film received may have been due to public frustration with the legal system, as the film achieves justice for the victim, whereas no one was ever convicted of raping Leigh. Brien cited the film as an example of why sensitivity and care must be taken when fictionalising an actual crime.[37] Home mediaA region 1 DVD was released on 29 October 2002 containing the original version of the film.[38] A region 4 DVD was released on 19 November 2003 containing the edited version. Special features included a four-minute featurette, cast and crew interviews, a 'goof reel' which included footage of a bonding trip made by Simon Lyndon, Laurence Bruels and Cameron Nugent to Lennox Head, and the film's original trailer and television advertisement. According to Andrew L. Urban from Urban Cinefile the featurette was "overburdened" with clips from the film, but was otherwise of interest. Urban also praised the seven-minute interview with Nick Enright.[39] Historical accuracyNone of the promotional material for the film mentioned Leigh and the film was not marketed as being "based on a true story".[9] The film's credits state that it is a work of fiction and that resemblance to "actual events or persons living or dead is entirely coincidental".[40] Nevertheless, numerous comparisons between the film and Leigh's murder were made.[9] Just like the play it was based on, Blackrock was often incorrectly considered by viewers to be a factual account of Leigh's murder.[9] Conflation between the two subjects was high; the film was described by Miriam Davis on radio station FM 91.5 as being the true story of "the murder of Leigh Warner at Blackrock Beach near Newcastle."[37] Donna Lee Brien stated that every review of both the film and the play it was based on at least mentioned Leigh, with some going into great detail on the subject.[9] Kerry Carrington stated that the film was very accurate in some aspects of the murder, yet very distant in others, as if the film was "having a bet each way".[20] Jared is an entirely fictional character, though he has been interpreted as a metaphor for everyone who witnessed Leigh being publicly assaulted yet did nothing.[9] In the film, Tracy does not ask her parents for permission to attend the party as she knows this would be denied, whereas Leigh obtained permission from her parents, who were told the party would be supervised. Tracy wears a short skirt, tight-fitting top, and wedged-heels to the party, while Leigh wore ordinary shorts, a jumper, and sand-shoes.[9][41] Tracy's body is found that night by a girl; Leigh's body was found the next day by a boy.[9] Tracy's mother packs up her daughter's bedroom the following day, whereas Leigh's mother left her room untouched for months. In the film, police labour until every boy involved in the rape and murder is punished,[36] whereas no one was convicted for raping Leigh and police received criticism for alleged incompetence. Tracy's murderer was 22 years old, well-toned, and committed suicide, while Leigh's was 18 years old, 120 kg (265 lb), and was jailed.[9] Both murderers, however, were high-school dropouts who were interested in mechanics, were considered to have no emotional depth, and were prone to violence. The party in the film was considered to be "an almost perfect re-creation" of the party in Stockton; a surf club is hired for the night with teenage attendees being entertained by a high-school band. The party spills out into the surrounding area where there are fights, and teenagers are seen stumbling, vomiting and unconscious. Tracy's funeral was also considered to be "a direct re-staging" of Leigh's service; both Leigh and Tracy's friends placed red roses on her coffin and then plant a tree in her memory. Both Leigh and Tracy's mothers worked at a nursing home and both their fathers called for the death penalty for her murderer. Parents are blamed for neglecting their children in both cases.[9] Details that were considered to be undoubtedly taken from Leigh's murder included the filming location of Stockton, the presence of the song "If I Could Turn Back Time" featured at Leigh's funeral appearing in the original script (though it did not appear in the finished film), and posters reading "Shame Blackrock Shame" seen on telegraph poles following Tracy's murder;[41] posters appeared around Stockton following Leigh's murder stating "Shame Stockton Shame: Dob the gutless bastards in".[9] AccoladesBlackrock received five nominations at the 1997 AACTA Awards, though did not win any awards.[42][43] It won both the 'Feature Film – Adaptation' award and the Major Award at the 1997 AWGIE Awards.[44]

Notes

ReferencesCitations

Sources

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||