|

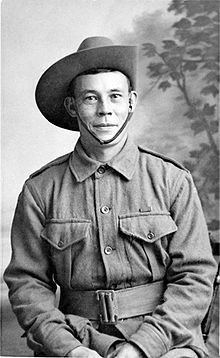

Billy Sing

William Edward Sing, DCM (3 March 1886 – 19 May 1943), known as Billy Sing, was an Australian soldier of Chinese and English descent who served in the Australian Imperial Force during World War I, best known as a sniper during the Gallipoli Campaign.[1][2][3][4][a] He took at least 150 confirmed kills during that campaign, and may have had over 200 kills in total.[3][4] However, contemporary evidence puts his tally at close to 300 kills.[5] Towards the end of the war, Sing married a Scottish woman, but the relationship did not last long.[2] Following work in sheep farming and gold mining, he died in relative poverty and obscurity in Brisbane during World War II.[2][6] Early lifeSing was born on 3 March 1886 in Clermont, Queensland, Australia, the son of a Chinese father and an English mother.[4][7][8][9] His parents were John Sing (c. 1842–1921), a drover from Shanghai, China, and Mary Ann Sing (née Pugh; c. 1857–unknown), a nurse from Kingswinford, Staffordshire, England.[10][11][b][12] Sing's mother had given birth to a daughter named Mary Ann Elizabeth Pugh on 28 May 1883, less than two months before marrying Sing's father on 4 July 1883.[13] It is unclear whether this child was John Sing's daughter as well.[14] A daughter, Beatrice Sing, was later born into the family on 12 July 1893.[15] The three children grew up together on the farm run by the Sings, and all three performed well academically.[16] There was considerable anti-Chinese sentiment in Australia at this time.[9][17] As a boy, Sing was well known for his shooting skill, but was the subject of racial prejudice due to his ancestry.[18] He began work hauling timber as a youth,[9] and later worked as a stockman and a sugarcane cutter.[1][2] Sing became well known for his marksmanship, both as a kangaroo shooter and as a competitive target shooter.[2][8] In the latter role, he was a member of the Proserpine Rifle Club (one of the many rifle clubs in Queensland that were partially sponsored by the Queensland and Australian defence forces to develop shooting skills).[2][19][20] He regularly won prizes for his shooting, and also played cricket with skill.[21] On 24 October 1914, two months after the outbreak of war, Sing enlisted as a trooper in the Australian 5th Light Horse Regiment of the Australian Imperial Force.[2][4][22][23] His Certificate of Medical Examination at the time showed that he stood at 5 ft 5 in (165 cm) and weighed 141 pounds (64 kg).[24] According to John Laws and Christopher Stewart, he was accepted into the army only after a recruitment officer chose to disregard the fact that Sing was part Chinese; at the time, only those of European ancestry were generally considered suitable for Australian military service.[25][26][27] Military serviceGallipoli Campaign Sing began his military career as part of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) forces in the Gallipoli Campaign in modern day Turkey. Biographer John Hamilton described the Turkish terrain thus: "It is a country made for snipers. The Anzac and Turkish positions often overlooked each other. Each side sent out marksmen to hunt and stalk and snipe, to wait and shoot and kill, creeping with stealth through the green and brown shrubbery ..."[28] Sing partnered with spotters Ion 'Jack' Idriess and, later, Tom Sheehan.[2] The spotter's task was to observe (spot) the surrounding terrain and alert the sniper to potential targets.[29] Idriess described Sing as "a little chap, very dark, with a jet black moustache and goatee beard. A picturesque looking mankiller. He is the crack shot of the Anzacs."[11] Chatham's Post, a position named after a Light Horse officer, was Sing's first sniping post.[2] Biographer Brian Tate wrote, "It was here that Billy Sing began in earnest his lethal occupation."[2] He set about his task with a Lee–Enfield .303 rifle.[30] An account by Private Frank Reed, a fellow Australian soldier, states that Sing was so close to the Turkish lines that enemy artillery rarely troubled him.[3] His comrades left three particular enemy positions to his attention: a trench at 350 yards (320 m) from his post, a communication sap at 500 yards (460 m), and a track in a gully at 1,000 yards (910 m).[3] According to Reed, "Every time Billy Sing felt sorry for the poor Turks, he remembered how their snipers picked off the Australian officers in the early days of the landing, and he hardened his heart. But he never fired at a stretcher-bearer or any of the soldiers who were trying to rescue wounded Turks."[3] In contrast, Hamilton said in a 2008 interview, "We have an anecdote where, after spotting an injured Turk, he said 'I'll put that poor cuss out of his agony' and just shot him. He was a very tough man."[9] Sing's reputation resulted in a champion Turkish sniper, nicknamed 'Abdul the Terrible' by the Allied side, being assigned to deal with him.[2][30] Tate alleges that the Turks were largely able to distinguish Sing's sniping from that of other ANZAC soldiers, and that only the reports of incidents believed to be Sing's work were passed on to Abdul.[2] Through analysis of the victims' actions and wounds, Abdul concluded that Sing's position was at Chatham's Post.[2] After several days, Sing's spotter alerted him to a potential target, and he took aim, only to find the target—Abdul—looking in his direction.[2] Sing prepared to fire, trying not to reveal his position, but the Turkish sniper noticed him and began his own firing sequence.[2] Sing fired first and killed Abdul.[2] Very shortly thereafter, the Turkish artillery fired on Sing's position—he and his spotter barely managed to evacuate from Chatham's Post alive.[2] Near the beginning of August 1915, Sing was hospitalised for four days with influenza.[31] That same month, an enemy sniper's bullet struck Sheehan's spotting telescope, injuring his hands and face, and then hit Sing's shoulder, but the latter was back in action after a week's recuperation.[2][29][32][33] Sheehan was more severely wounded, and was shipped back to Australia.[2] This was reportedly the only time that Sing was injured at Gallipoli.[32] He would not fare so well later on in the war.  Sniping recordSing's marksmanship at Gallipoli saw him dubbed 'The Assassin' or 'The Murderer' by his comrades.[7][30][34] He reportedly acquired the latter nickname due to his callous attitude towards the enemy.[29][35] By early September 1915, he had taken 119 kills, according to Brigadier-General Granville Ryrie, commanding officer of the 2nd Australian Light Horse Brigade.[36] Regimental records list Sing as having taken 150 confirmed kills, but on 23 October 1915, General William Birdwood, commander of ANZAC forces, issued an order complimenting him on his 201 unconfirmed kills.[2][32] Historian Bob Courtney noted that an official kill was recorded only if the spotter saw the target fall.[29] If the first shot missed the target, it was very risky to take a second shot, as this could give away the sniper team's position.[29] Major Stephen Midgely estimated Sing's tally at close to 300 kills.[5] Midgely had brought him to the attention of Birdwood, who in turn had told Lord Kitchener that "if his troops could match the capacity of the Queensland sniper the allied forces would soon be in Constantinople."[29] Birdwood had reportedly joined Sing as his spotter on one occasion, and had the opportunity to witness his marksmanship first hand.[2][29] In February 1916, Sing was Mentioned in Despatches by General Sir Ian Hamilton, Commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force.[2][8][32][37] This was the first official recognition of his service.[32] On 10 March 1916, he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal,[2][8][29][32][38] with a related entry in military records reading: "For conspicuous gallantry from May to September, 1915, at Anzac, as a sniper. His courage and skill were most marked, and he was responsible for a very large number of casualties among the enemy, no risk being too great for him to take."[39] Apart from the recognition he received from his superiors, Sing's exploits were also reported in British and American newspapers of the time.[2][9][32][40] Western FrontAt the end of November 1915, Sing suffered from myalgia and was confined to the hospital ship HMHS Gloucester Castle for almost two weeks.[41] During this time, he was conveyed to Malta, then Ismaïlia, Egypt.[42] While in Egypt, he was also hospitalised with parotitis and mumps, but rejoined his unit at the end of March 1916.[42] Australian soldiers stationed in Egypt including Billy Sing were major customers of Egyptian prostitutes in the local red light districts and brothels. High prices by the prostitutes led to the Wasser red light area becoming the scene of a major riot by New Zealand and Australian soldiers on Good Friday in 1915.[43] Sing transferred to the 31st Infantry Battalion on 27 July 1916 at Tel-el-Kibir and sailed to England the following month.[44] Following a brief period of training in England, he sailed for France and entered action on the Western Front in January 1917.[2][25][44] He was wounded in action several times,[2][9][25] and commended many times in reports by Allied commanders.[25] In March 1917, he was wounded in the left leg and hospitalised in England.[45] In May 1917, while recovering in Scotland, he met waitress Elizabeth A. Stewart (c. 1896–unknown),[2][9][33][46] who was the daughter of Royal Navy cook George Stewart.[26][46] The two were married on 29 June 1917 in Edinburgh.[2][9][25][46][c] In July 1917, Elizabeth Sing's address was noted in records as 6 Spring Gardens, Stockbridge, Edinburgh.[47] After a month with his new wife, Sing returned to the trenches in France in August 1917,[25][33][48] but was in very poor health due to his battle wounds and the effects of gas poisoning.[8][33] It is not clear whether he operated as a sniper on the Western Front, but in September 1917, he led a unit in the Battle of Polygon Wood in counter-sniper operations.[2][25] For this action, he was awarded the Oorlogskruis (Belgian Croix de Guerre) in 1918,[2][25][49] and was also recommended for the Military Medal—but never received it.[2][9][25] In November 1917, he was confined to hospital again due to problems with his previously wounded leg.[48] In mid-February 1918, he was hospitalised due to a gunshot wound in the back.[50] Sing suffered lung disease from his exposure to gas, and it soon brought his military career to an end.[33] Return to civilian lifeSing returned to Australia on submarine guard duty in late July 1918.[2][51][52] An army medical report from 23 November 1918 noted that he had gunshot wounds in the left shoulder, back, and left leg, and had suffered gas poisoning.[53] The report stated that his general health was 'good' but that he complained of coughing upon exertion.[53] It recognised that Sing's disability were the result of service, was permanent, and recommended that he be discharged as permanently unfit for service.[53] Following his departure from the army, he briefly turned his hand to sheep farming, but the land he was given was of poor quality.[33] He then worked as a gold miner.[33] According to some accounts, Sing and his wife were honoured by the local community when they arrived in Proserpine, Queensland, in late 1918.[2][54][55] Other accounts, however, state that although Sing arranged for passage from Scotland to Australia for his wife, there was no evidence that she made the journey.[9][26][33][d] If Sing's wife did come to Australia, it appears that she left her husband after a few years;[2][54] Tate suggests that the "transition from the green hills and ancient culture of Edinburgh to the dust and rough life of the mining district around Clermont must have been traumatic for Elizabeth Sing" and might have been a reason for her departure.[2] Recent research has shown that Elizabeth remained in Edinburgh. She had had a daughter (Mary) in 1919 and a son (Theo) in 1924, to different fathers (neither of whom was Billy Sing). She travelled to Australia during 1925 with her two children, and settled in Paddington, NSW. She adopted the surname of her son's father. She lived in New South Wales with her son's father until her death in Wollongong in the 1970s. It is not known whether she had any contact with Billy after her arrival in Australia.[56] Later life and death In later life, Sing reported chest, back, and heart pain.[33] His final days were spent in relative poverty and obscurity.[9] His elder sister or half-sister, Mary Ann Elizabeth, had died in childbirth in 1915.[15] In 1942, Sing moved from Miclere to Brisbane, telling his surviving sister Beatrice that it was cheaper to live there.[2][55][57] His final occupation was as a labourer.[55] Sing died alone in his room in a boarding house in West End, Brisbane, on 19 May 1943.[2][8][33][55] The cause of death was a ruptured aorta.[2][54] His only significant possessions were a hut (worth around £20) on a mining claim and a mere 5 shillings found with him in his room.[2][33] There was no sign of his medals from World War I, and his employers owed him around £6 in wages.[2] Sing was buried in the Lutwyche War Cemetery,[58] in Kedron, a northern suburb of Brisbane.[8][33][59] His grave is now part of the lawn cemetery section of the Lutwyche Cemetery,[60] and the inscription on his bronze plaque reads:

LegacyThe Queensland Military Historical Society set up a bronze plaque at 304 Montague Road, South Brisbane, where Sing had died.[33][54] In 1995, a statue of Sing was unveiled with honour in his home town of Clermont.[33] In 2004, an Australian Army sniper team in Baghdad named their post the 'Billy Sing Bar & Grill.'[33] On 19 May 2009, the 66th anniversary of Sing's death, the Chinese Consul-General, Ren Gongping, along with Returned and Services League of Australia officers and community leaders, laid wreaths at his grave.[8][33][62] Ren said, "Billy Sing is a symbol of the long history of Chinese in Australia, and the great role they have played in your nation's past ... It also reminds us that China and Australia were allies through both world wars, and that we have a long and proud shared past."[8]  Sing's life was recounted in a chapter of Laws and Stewart's book, There's always more to the story (2006),[63] and in greater depth by Hamilton in his book, Gallipoli Sniper: The life of Billy Sing (2008).[9][64][65] Hamilton's book includes a detailed account of how snipers worked at Gallipoli and their contribution to the progress of the campaign.[66] Reviewer John Wadsley wrote that "Hamilton is able to bring together a range of sources to create the story, and while at times, you get the feeling he is padding it out to make up for the lack of direct material about Billy Sing, the book works."[67] A television mini-series, The Legend of Billy Sing, was in post-production as of 2010.[68] Despite some reports that it was based on Hamilton's book, the author maintained that he was never contacted by the film makers.[69][70] Although Sing and his father were partly Chinese and fully Chinese, respectively, the mini-series portrayed them with actors of European ancestry.[71][72][73][74][75] The director, Geoff Davis, was criticised for this decision.[71][72][73][74][75][76][77][f] Politician Bill O'Chee, a member of the Billy Sing Commemorative Committee, said, "When a person dies, all that is left is their story, and you can’t take a person’s name and not tell the truth about their story."[74] Davis has said, "Whatever [Sing's] genetic background, his culture was Australian. To me, he's very representative of every Australian whose parents were not born here. ... A lot of people are sitting at the back of this bus attacking the driver. A lot of people feel they own the story of Billy Sing. But they've probably got more resources than me—if they want to tell that story, then tell it."[71] Hamilton characterised Sing as "a cold-blooded killer ... [yet] a man with a sense of humour ... the Anzac angel of death,"[78] and Laws and Stewart described him simply as "one of many Australians of Chinese descent who served with distinction in the Australian forces during World War I."[25] Around 400 people of Chinese descent served in Australia's military forces during the 20th century.[27] For the 100th anniversary commemoration of the Gallipoli landings, a monument was erected to Sing in the Lutwyche Cemetery in Brisbane, near his grave stone, by the 31st Battalion Association Brisbane Branch, in conjunction with Kedron Wavell RSL, Chermside and District Historical Society, and Chinese Association of Queensland. It was officially unveiled on the anniversary of his death.[79][57] Each year on the weekend immediately before Anzac Day (25 April), the William 'Billy' Sing Memorial Shooting Competition is held at the North Arm Rifle Range on the Sunshine Coast in Queensland using the Lee Enfield military service rifle. The competition is held over several hundred metres worth of stages with the highest scorer awarded the William 'Billy' Sing Memorial Trophy.  See alsoNotesa. ^ There appears to have been at least one other Australian soldier named William Sing who fought in World War I.[80] b. ^ Sing's father was also known as Richard Sing.[10] Sing's paternal grandfather was See Sing.[10] Sing's mother arrived in Australia in 1881.[14] Sing's maternal grandparents were John Pugh, a clerk, and Mary Ann Pugh (née Pearson).[14] c. ^ A certified extract of the Sings' marriage certificate shows that Sing's father had died by this time,[46] but Hamilton states that Sing's father died in 1921, four years after the wedding.[10] d. ^ Historian Alastair Kennedy (2009) reported that Sing's medical records from December 1917, a few months after he married, stated that he was diagnosed at first with venereal disease and then syphilis.[26] Kennedy hypothesises that Elizabeth Sing might have learned of her husband's condition and decided to end the marriage.[26] e. ^ The spelling "Croux De Guerre" is as it appears on Sing's headstone.[60] f. ^ Mini-series director Geoff Davis asserted that he could not find a 60-year-old Chinese actor to play Sing's father;[70] Chinese Australian actors Warren Lee and Tony Chu have expressed disagreement with this assertion.[81] According to Australia's SBS, Davis said that he called for actors willing to work pro bono or for deferred payment, but no Chinese actors responded.[82] Josh Davis, the director's son, was cast as Sing.[71][72] Tony Bonner was cast as Sing's father.[71] Apart from Australia, the controversy has been reported in Canada,[83][84] Kuwait,[85] Macau,[86] Malaysia,[87] New Zealand,[88] Singapore,[89] Taiwan,[90][91] Thailand,[92] and the United Kingdom.[75] ReferencesCitations

Sources

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||