|

Battle of Vilnius (1812)

French invasion of Russia: Battle of Vilnius Current battle Other battles

Description

The Battle of Vilnius (Vilna in Russian, Wilno in Polish), in 1812 was part of Napoléon Bonaparte's invasion of Russia, a campaign famously marked by its logistical and environmental challenges, ultimately leading to a disastrous retreat for the French Grande Armée. The battle took place from June 28–29, 1812 in Vilnius (then part of the Russian Empire, now the capital of Lithuania), soon after Napoleon launched his invasion by crossing the Nieman River. BackgroundNapoleon goal was to enforce his Continental System, which aimed to block trade between Britain and the rest of Europe. Russia’s defiance of this embargo led to Napoleon’s decision to invade, with a massive force of over 600,000 soldiers drawn from various parts of his empire.[3] The campaign began in June 1812 (also known as French invasion of Russia or Sixth Coalition), with Napoleon’s Grande Armée marching into Russia. Despite initial successes, including the capture of Moscow, the French forces faced severe logistical problems, including lack of supplies and the Russian tactic of scorched earth, which deprived Napoleon of the resources needed to sustain his army. The harsh Russian winter and persistent Russian military pressure compounded the difficulties, leading to heavy casualties and a disastrous retreat.[3] The failure of the invasion marked a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars. It significantly weakened Napoleon's army, and the remnants of the Grande Armée were effectively destroyed during the retreat. This defeat ultimately contributed to Napoleon's downfall and reshaped European geopolitics.[3] HistoryThe Battle in June 1812 was a key early encounter during Napoleon's invasion of Russia. As the French army advanced, Vilnius became a strategic target for Napoleon, who hoped to secure the city quickly and force a decisive battle with Russian forces. However, the Russian army, under commanders such as General Mikhail Barclay de Tolly, effectively evaded direct engagement by strategically retreating, leaving Vilnius vulnerable. The French forces, led by Marshal Joachim Murat, Marshal Michel Ney, and Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout entered Vilnius on June 28, only to find that much of the city’s supplies and infrastructure had been destroyed by the retreating Russians to slow the French advance and deprive them of resources.[4][3] French occupation and Russian withdrawal Minard's latest (modern) version of the French casualties map. See also Attrition warfare against Napoleon.

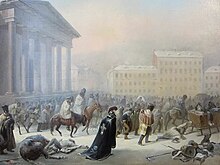

Russian forces under Barclay de Tolly, Prince Pyotr Bagration, and Commander Alexander Ivanovich heavily outnumbered and unprepared to confront Napoleon's massive force,[3] chose to abandon Vilnius without offering significant/major resistance. The retreat was a part of the Russian strategy called Fabian strategy by drawing Napoleon further into Russian territory while stretching his supply lines, rather than engaging in a full-scale confrontation. Napoleon's troops entered Vilnius on June 28, with little opposition.[5] Weather and Logistical StrugglesAlthough the battle itself was brief and resulted in minimal fighting, the entry into Vilnius highlighted some of the critical issues that would later impact Napoleon’s campaign. The intense summer heat caused thousands of soldiers to fall ill due to dehydration, heat exhaustion, and dysentery. Heavy rains followed soon after, turning roads into mud and slowing down Napoleon’s forces, further straining their supplies.[6][7] Supply IssuesThe French troops suffered severe logistical problems. Supplies, stretched thin due to the rapid advance and the scorched-earth tactics used by the retreating Russians, became a primary concern. Vilnius offered limited resources, and its capture failed to resolve Napoleon's growing supply crisis, which would worsen as his army moved further east.[6] AftermathThe consequences for the French forces were catastrophic. Troop movements were severely hindered or completely halted, while the extensive troop and supply trains along the Vilnius-Kaunas Road descended into chaos. The roads, reduced to near impassable quagmires, placed overwhelming strain on the horses, many of which succumbed to exhaustion. The disruption and frequent loss of supply trains left both soldiers and horses struggling to survive. Although Napoleon's transportation corps had historically ensured reliable supply lines, they were overwhelmed and insufficient during the invasion.[8][9]  Napoleon and his army retreating from Russia several weeks/months later after the Battle of Borodino, and the burning of Moscow.

After occupying Vilnius, Napoleon regroup with the French army that continued to push deeper into Russia but suffered immense logistical challenges. Following the Battle of Borodino, and the occupation of Moscow, Napoleon's forces were decimated by harsh weather and Russian resistance during the retreat, culminating in the crossing of the Berezina River in November.[5]  Napoleon and his army crossing the Berezina River (Napoleon retreat, Plassenburg Zinnfiguren Museum)

Napoléon departed for France after ordering his generals to hold Vilna. Fresh troops had been stationed there to serve as a buffer for the retreating army. However, these reinforcements, unaccustomed to the brutal cold and often too young to have endured such hardship, suffered catastrophic losses—one division lost half its men on the first day and the rest before the main army arrived. The French hoped Vilna would offer some reprieve, but the city proved indefensible, and Cossacks soon flooded in. To the west of Vilna, on an icy hill too treacherous to traverse, the French were forced to abandon the Imperial treasury, leaving looters free to make off with sacks of gold coins. The last French officer to cross the Niemen River back into Poland was Marshal Michel Ney, who had been conducting a rear-guard action and crossed nearly alone.[1] Following the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, many of the Polish-Lithuanian officers, soldiers, 1st Light Cavalry Lancers Regiment of the Imperial Guard (Polish), and several Polish-Lithuanian cavalry regiments (17th Lithuanian Lancer Regiment, 3rd Light Cavalry Lancers Regiment of the Imperial Guard (Lithuanian)) ended up exiled in France after the defense of Paris. A volunteers squardon in Elba called Elba Squadron of Polish/Elba Honor Squadron tasked to guard Napoleon while exiled.[5] After Napoleon's exile to Saint Helena by the Coalition following the Hundred Days' Campaign, they were released from exile.[5] ArtifactsIn 2001, a mass grave containing at least 3,269 skeletons was uncovered in Vilnius, Lithuania. These remains were identified as soldiers from Napoleon's Grande Armée, based on artifacts such as:[10]

See Also

Reference

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||