|

Bal des Ardents

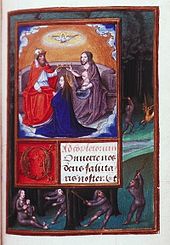

The Bal des Ardents (Ball of the Burning Men[1]), or the Bal des Sauvages[2] (Ball of the Wild Men), was a masquerade ball[note 1] held on 28 January 1393 in Paris, France, at which King Charles VI had a dance performance with five members of the French nobility. Four of the dancers were killed in a fire caused by a torch brought in by Louis I, Duke of Orléans, the king's brother. The ball was one of a series of events organised to entertain Charles, who suffered an attack of insanity in the previous summer of that year. The circumstances of the fire undermined confidence in the king's capacity to rule; Parisians considered it proof of courtly decadence and threatened to rebel against the more powerful members of the nobility. The public's outrage forced Charles and his brother Orléans, whom a contemporary chronicler accused of attempted regicide and sorcery, to offer penance for the event. Charles' wife, Isabeau of Bavaria, held the ball to honor the remarriage of a lady-in-waiting. Scholars believe the dance performed at the ball had elements of traditional charivari,[3] with the dancers disguised as wild men, mythical beings often associated with demonology, that were commonly represented in medieval Europe and documented in revels of Tudor England. The event was chronicled by contemporary writers such as the Monk of St Denis and Jean Froissart, and illustrated in 15th-century illuminated manuscripts by painters such as the Master of Anthony of Burgundy. The incident later provided inspiration for Edgar Allan Poe's short story "Hop-Frog." BackgroundIn 1380, after the death of his father Charles V of France, the 12-year-old Charles VI was crowned king, beginning his minority with his four uncles acting as regents.[note 2][4] Within two years, one of his uncles, Philip of Burgundy, described by historian Robert Knecht as "one of the most powerful princes in Europe",[5] became sole regent to the young king after Louis of Anjou pillaged the royal treasury and departed to campaign in Italy. On the other hand, Charles' other two uncles; John of Berry and Louis of Bourbon, showed little interest in governing.[4] In 1387, the 20-year-old Charles assumed sole control of the monarchy and immediately dismissed his uncles and reinstated the Marmousets, his father's traditional counselors. Unlike his uncles, the Marmousets wanted peace with England, less taxation and a strong, responsible central government—policies that resulted in a negotiated three-year truce with England, and the Duke of Berry being stripped of his post as governor of Languedoc because of his excessive taxation.[6]  In 1392, Charles suffered the first in a lifelong series of attacks of insanity, manifested by an "insatiable fury" at the attempted assassination of the Constable of France and leader of the Marmousets, Olivier de Clisson—carried out by Pierre de Craon but orchestrated by John IV, Duke of Brittany. Convinced that the attempt on Clisson's life was also an act of violence against himself and the monarchy, Charles quickly planned a retaliatory invasion of Brittany with the approval of the Marmousets, and within months departed Paris with a force of knights.[6][7] On a hot August day outside Le Mans, accompanying his forces on the way to Brittany, Charles drew his weapons without warning and charged his own household knights including his brother Louis I, Duke of Orléans—with whom he had a close relationship—crying, "Forward against the traitors! They wish to deliver me to the enemy!"[8] The king killed four men[9] before his chamberlain grabbed him by the waist and subdued him, after which he fell into a coma that lasted for four days. Few believed he would recover; his uncles, the dukes of Burgundy and Berry, took advantage of the king's illness and quickly seized power, re-established themselves as regents and dissolved the Marmouset council.[7] The comatose king was returned to Le Mans, where Guillaume de Harsigny—a venerated and well-educated 92-year-old physician—was summoned to treat him. After Charles regained consciousness and his fever subsided, he was returned to Paris by Harsigny, moving slowly from castle to castle with periods of rest in between. Late in September, Charles was well enough to make a pilgrimage of thanks to Notre-Dame de Liesse near Laon, after which he returned again to Paris.[7]  Charles' sudden onset of insanity was seen by some as a sign of divine anger and punishment, and by others as the result of sorcery;[7] modern historians such as Knecht speculate that Charles was experiencing the onset of paranoid schizophrenia.[6] The king continued to be mentally fragile, believing he was made of glass, and according to historian Desmond Seward, running "howling like a wolf down the corridors of the royal palaces."[10] Contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart wrote that Charles' illness was so severe that he was "far out of the way; no medicine could help him."[11] During the worst of his illness the king was unable to recognize his wife, Isabeau of Bavaria, demanding her removal when she entered his chamber, but after his recovery he made arrangements for her to hold guardianship of their children. Isabeau eventually became guardian to her son, the future Charles VII (b. 1403), granting her great political power and ensuring a place on the council of regents in the event of a relapse.[12] In A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century, the historian Barbara Tuchman writes that the physician Harsigny, refusing "all pleas and offers of riches to remain,"[13] left Paris and ordered the courtiers to shield Charles VI from the duties of government and leadership. He told the king's advisors to "be careful not to worry or irritate him .... Burden him with work as little as you can; pleasure and forgetfulness will be better for him than anything else."[1] To surround Charles with a festive atmosphere and to protect him from the rigor of governing, the court turned to elaborate amusements and extravagant fashions. Isabeau and her sister-in-law Valentina Visconti, Duchess of Orléans, wore jewel-laden dresses and elaborate braided hairstyles coiled into tall shells and covered with wide double hennins that reportedly required doorways to be widened to accommodate them.[1] The common people thought the extravagances excessive yet loved their young king, whom they called Charles le bien-aimé (the well-beloved). Blame for unnecessary excess and expense was directed at the foreign queen, who was brought from Bavaria at the request of the king's uncles.[1] Neither Isabeau nor her sister-in-law Valentina—daughter of the ruthless Duke of Milan—were well liked by either the court or the people.[9] Froissart wrote in his Chronicles that Charles' uncles were content to allow the frivolities because "so long as the Queen and the Duc d'Orléans danced, they were not dangerous or even annoying."[14] Bal des Ardents and aftermath On 28 January 1393, Isabeau held a masquerade at the Hôtel Saint-Pol to celebrate the third marriage of her lady-in-waiting, Catherine de Fastaverin.[2][note 3] Tuchman explains that a widow's remarriage was traditionally an occasion for mockery and tomfoolery, often celebrated with a charivari characterized by "all sorts of licence, disguises, disorders, and loud blaring of discordant music and clanging of cymbals".[3] On the suggestion of Huguet de Guisay, whom Tuchman describes as well known for his "outrageous schemes" and cruelty, six young men, including Charles, performed a dance in costume as wood savages.[15] The costumes, which were sewn onto the men, were made of linen soaked with resin to which flax was attached "so that they appeared shaggy and hairy from head to foot".[1] Masks made of the same materials covered the dancers' faces and hid their identities from the audience. Some chronicles report that the dancers were bound together by chains. Most of the audience were unaware that the king was among the dancers. Strict orders forbade the lighting of hall torches and prohibited anyone from entering the hall with a torch during the performance, to minimize the risk of the highly flammable costumes catching fire.[1] According to historian Jan Veenstra, the dancers capered and howled "like wolves", spat obscenities and invited the audience to guess their identities while dancing in a "diabolical" frenzy.[16] Charles's brother Orléans arrived with Philippe de Bar, late and drunk, and they entered the hall carrying lit torches. Accounts vary, but Orléans may have held his torch above a dancer's mask to determine his identity when a spark fell, setting fire to the dancer's leg.[1] In the 17th century, William Prynne wrote of the incident that "the Duke of Orleance ... put one of the Torches his servants held so neere the flax, that he set one of the Coates on fire, and so each of them set fire on to the other, and so they were all in a bright flame",[17] whereas a contemporary chronicle stated that he "threw" the torch at one of the dancers.[2] Isabeau, knowing that her husband was one of the dancers, fainted when the men caught fire. Charles, however, was standing at a distance from the other dancers, near his 15-year-old aunt Joan, Duchess of Berry, who swiftly threw her voluminous skirt over the king to protect him from the sparks.[1] Sources disagree as to whether the duchess moved into the dance and drew the king aside to speak to him, or whether the king moved away toward the audience. Froissart wrote that "The King, who proceeded ahead of [the dancers], departed from his companions ... and went to the ladies to show himself to them ... and so passed by the Queen and came near the Duchess of Berry".[18][19]  The scene soon descended into chaos; the dancers shrieked in pain as they burned in their costumes, and the audience, many of them also sustaining burns, screamed as they tried to rescue the burning men.[1] The event was chronicled in uncharacteristic vividness by the Monk of St Denis, who wrote that "four men were burned alive, their flaming genitals dropping to the floor ... releasing a stream of blood".[16] Only two dancers survived: the king, thanks to the quick reactions of the Duchess of Berry, and the Sieur de Nantouillet, who jumped into an open vat of wine and remained there until the flames were extinguished. The Count of Joigny died at the scene; Yvain de Foix, son of Gaston Fébus, Count of Foix, and Aimery of Poitiers, son of the Count of Valentinois, lingered with painful burns for two days. The instigator of the affair, Huguet de Guisay, survived a day longer, described by Tuchman as bitterly "cursing and insulting his fellow dancers, the dead and the living, until his last hour."[1] The citizens of Paris, angered by the event and at the danger posed to their monarch, blamed Charles' advisors. A "great commotion" swept through the city as the populace threatened to depose the king's uncles and kill dissolute and depraved courtiers. Greatly concerned at the popular outcry and worried about a repeat of the Maillotin revolt of the previous decade—when Parisians armed with mallets turned against tax collectors—Charles' uncles persuaded the court to do penance at Notre Dame Cathedral, preceded by an apologetic royal progress through the city in which the king rode on horseback with his uncles walking in humility. Orléans, who was blamed for the tragedy, donated funds in atonement for a chapel to be built at the Celestine monastery.[1][20] Froissart's chronicle of the event places blame directly on Orléans. He wrote: "And thus the feast and marriage celebrations ended with such great sorrow ... [Charles] and [Isabeau] could do nothing to remedy it. We must accept that it was no fault of theirs but of the duke of Orléans."[21] Orléans' reputation was severely damaged by the event, compounded by an episode a few years earlier in which he was accused of sorcery after hiring an apostate monk to imbue a ring, dagger and sword with demonic magic. The theologian Jean Petit later testified that Orléans practiced sorcery, and that the fire at the dance represented a failed attempt at regicide made in retaliation for Charles' attack the previous summer.[22] The Bal des Ardents added to the impression of a court steeped in extravagance, with a king in delicate health and unable to rule. Charles' attacks of illness increased in frequency such that by the end of the 1390s his role was merely ceremonial. By the early 15th century he was neglected and often forgotten, a lack of leadership that contributed to the decline and fragmentation of the Valois dynasty.[23] In 1407, Philip of Burgundy's son, John the Fearless, had his cousin Orléans assassinated because of "vice, corruption, sorcery, and a long list of public and private villainies"; at the same time Isabeau was accused of having been the mistress of her husband's brother.[24] Orléans' assassination pushed the country into a civil war between the Burgundians and the Orléanists (known as the Armagnacs) which lasted for several decades. The vacuum created by the lack of central power and the general irresponsibility of the French court resulted in it gaining a reputation for lax morals and decadence that endured for more than 200 years.[25] Folkloric and Christian representations of wild men Veenstra writes in Magic and Divination at the Courts of Burgundy and France that the Bal des Ardents reveals the tension between Christian beliefs and the latent paganism that existed in 14th-century society. According to him, the event "laid bare a great cultural struggle with the past but also became an ominous foreshadowing of the future."[16] Wild men or savages—usually depicted carrying staves or clubs, living beyond the bounds of civilization without shelter or fire, lacking feelings and souls—were then a metaphor for man without God.[26] Common superstition held that long-haired wild men, known as lutins, who danced to firelight either to conjure demons or as part of fertility rituals, lived in mountainous areas such as the Pyrenees. In some village charivaris at harvest or planting time dancers dressed as wild men, to represent demons, were ceremonially captured and then an effigy of them was symbolically burnt to appease evil spirits. The church, however, considered these rituals pagan and demonic.[27][note 4]  Veenstra explains that it was believed that by dressing as wild men, villagers ritualistically "conjured demons by imitating them"—although at that period penitentials forbade a belief in wild men or an imitation of them, such as the costumed dance at Isabeau's event. In folkloric rituals the "burning did not happen literally but in effigie", he writes, "contrary to the Bal des Ardents where the seasonal fertility rite had watered down to courtly entertainment, but where burning had been promoted to a dreadful reality." A 15th-century chronicle describes the Bal des Ardents as una corea procurance demone ("a dance to ward off the devil").[28] Because remarriage was often thought to be a sacrilege—common belief was that the sacrament of marriage extended beyond death—it was censured by the community. Thus the purpose of the Bal des Ardents was twofold: to entertain the court and to humiliate and rebuke Isabeau's lady-in-waiting—in an inherently pagan manner, which the Monk of St Denis seemed to dislike.[27] A ritual burning on the wedding night of a woman who was remarrying had Christian origins as well, according to Veenstra. The Book of Tobit partly concerns a woman who had seven husbands murdered by the demon Asmodeus; she is eventually freed of the demon by the burning of the heart and liver of a fish.[27][29] The event also may have served as a symbolic exorcism of Charles's mental illness at a time when magicians and sorcerers were commonly consulted by members of the court. In the early 15th century, ritual burning of evil, demonic or Satanic forces was not uncommon as shown by Orléans' later persecution of the king's physician Jehan de Bar, who was burned to death after confessing, under torture, to practicing sorcery.[27] ChroniclesThe death of four members of the nobility was sufficiently important to ensure that the event was recorded in contemporary chronicles, most notably by Froissart and the Monk of St Denis, and subsequently illustrated in copies of illuminated manuscripts. While the two main chroniclers agree on essential points of the evening—the dancers were dressed as wild men, the king survived, one man fell into a vat and four of the dancers died—there are discrepancies in the details. Froissart wrote that the dancers were chained together, which is not mentioned in the monk's account. The two chroniclers are also at odds about the purpose of the dance. According to the historian Susan Crane, the monk describes the event as a wild charivari with the audience participating in the dance, whereas Froissart's description suggests a theatrical performance without audience participation.[30]  Froissart wrote about the event in Book IV of his Chronicles (covering the years 1389 to 1400), an account described by scholar Katerina Nara as full of "a sense of pessimism", as Froissart "did not approve of all he recorded."[31] Froissart blamed Orléans for the tragedy,[32] while the monk blamed the instigator, de Guisay, whose reputation for treating low-born servants like animals earned him such universal hatred that "the Nobles rejoiced at his agonizing death".[33] The monk wrote of the event in the Histoire de Charles VI (History of Charles VI), covering about 25 years of Charles' reign.[34] He seemed to disapprove[note 5] on the grounds that the event broke social mores and the king's conduct was unbecoming, whereas Froissart described it as a celebratory event.[30]  Scholars are unsure whether either chronicler was present that evening. According to Crane, Froissart wrote of the event about five years later, and the monk about ten. Veenstra speculates that the monk was an eyewitness (as he was for much of Charles' reign) and that his account is the more accurate of the two.[30][36] The monk's chronicle is generally accepted as essential for understanding the king's court, however his neutrality may have been affected by his pro-Burgundian and anti-Orléanist stance, causing him to depict the royal couple in a negative manner.[37] A third account was written in the mid-15th century by Jean Juvenal des Ursins in his biography of Charles, L'Histoire de Charles VI: roy de France, not published until 1614.[38] The Froissart manuscript dating from between 1470 and 1472 from the Harleian Collection held at the British Library includes a miniature depicting the event, titled "Dance of the Wodewoses", attributed to an unknown painter referred to as the Master of the Harley Froissart.[35] A slightly later edition of Froissart's Chronicles, dated to around 1480, contains a miniature of the event, "Fire at a Masked Dance", also attributed to an unidentified early Netherlandish painter known as the Master of the Getty Froissart.[39] The 15th-century Gruuthuse manuscript of Froissart's Chronicles, held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, has a miniature of the event.[40] Another edition of Froissart's Chronicles published in Paris around 1508 may have been made expressly for Maria of Cleves. The edition has 25 miniatures in the margins; the single full-page illustration is of the Bal des Ardents.[41] Notes and references

References

Works cited

External linksWikiquote has quotations related to Bal des Ardents. Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bal des ardents. |