|

Ascosphaera aggregata

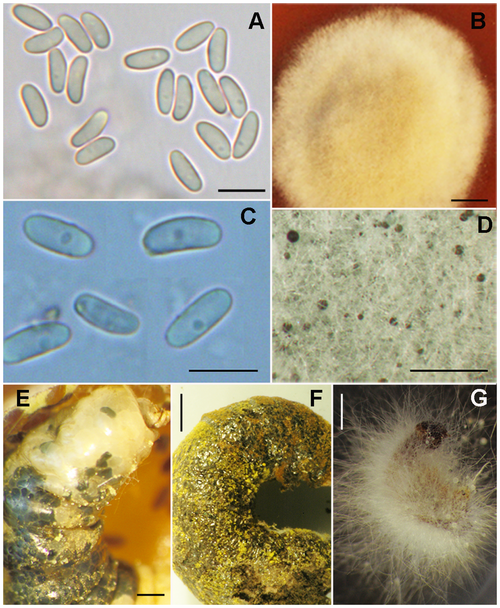

Ascosphaera aggregata is a species of fungus. History and taxonomyAscosphaera aggregata, discovered in 1975 by Jens-Peder Skou[1] is a fungus that is related to Ascosphaera apis.[2] Habitat and ecologyAscosphaera aggregata is an obligate parasite[3] that causes chalkbrood in bees,[4] symptom manifestations differ depending on age of the larva.[5] It primarily infects alfalfa leafcutting bees, Megachile rotundata.[2][6][7][3][8] Megachile rotundata infected with A. aggregata have been detected in the United States, Canada,[9] and South America.[5] Other bee species that A. aggregata has been seen to infect include the red mason bee (Osmia rufa[8]), the patchwork leafcutter bee (Megachile centuncularis[8]), Megachile pugnata and Megachile relativa.[2][10][8] Growth, morphology and pathobiologyAscosphaera aggregata is an obligate parasite that can cause chalkbrood by the fifth instar.[5] The majority of the life cycle and growth of A. aggregata occurs in M. rotundata larvae. Infection of bee larvae occurs only via ingestion of resting spores,[3] and is not possible via spore inhalation nor contact with the fungal vegetative form.[6][5] Spores develop in the larva and cause it to swell, bursting the larval integument (giving the dead larvae a ragged appearance)[1] and furthering the spread of the fungus. Buildup of larval cadavers traps the unaffected emerging bees, forcing them to chew through the cadavers and be covered in spores.[7] Bees covered in spores then contaminate food provisions for other broods[7] and spread the infection. Early vegetative growth utilizes gut lumen nutrients.[6] A. aggregata grows through the midgut wall to the hemocoele (event trigger is unknown, not because of lack of space nor food)[6] eventually replacing larval tissue.[3] Resulting larvae are filled with a mycelial mat comprising two layers: a dense inner layer and a less dense outer layer.[6] Sexual developmentAscospore morphology consists of two layers: an inner chitinous and smooth layer, and an outer layer that is rough, spotted,[1] and not composed of chitin nor cellulose.;[6]) Ascospore development in A. aggregata is very unique and the resulting structure is referred to as a "spore cyst", or "ascocyst" or "synascus".[8] Sexual development occurs on the outer mycelial mat in the subcuticular region,[3][6] and is documented to proceed as follows:

PhysiologyAscosphaera aggregata has been found to be unable to break down chitin.[6][3] Diagnostic considerationsAlthough ascospore development is very unique, it is very hard to identify A. aggregata because the spore balls and conidia tend to resemble other species.[12] Recent investigations by James and Skinner (2005)[12] have discovered that PCR of the ITS domain of ribosomal DNA with species specific primer sets allows the detection of fungal DNA (working, even, in asymptomatic individuals).[12] The PCR technique can also be used on hair and honey samples to avoid the difficulty of culturing spores,[12] as spore were shown before to only germinate well in lipids.[13] Storage of the fungus has also proven to be difficult as it collapses after 1–2 months during normal culture passaging.[14] However, Jensen et al. (2009) found that spores could be preserved via cryopreservation or freeze-drying whereas hyphae unfortunately could not be preserved.[14] Economic importanceMegachile rotundata is the primary pollinator of the commercially grown alfalfa seed,[11][7] accounting for 46,000 metric tonnes of North American alfafa seed (two-thirds the global production) in 2004.[7] M. rotundata is also the second most valuable field crop pollinator, behind the honey bee, because of the value of alfalfa in animal feed and hay.[7] A. aggregata has been killing this economic pollinator in the US since 1972[10] and has been reported to be able to kill greater than 50% of a population.[8] Effective management of the fungus has yet to be discovered, as the current registered treatment in Canada (paraformaldehyde fumigation of spores[7]) involves a carcinogen and other treatment options (heat and chloride treatments) are expensive and labour-intensive.[7] References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||