|

Ascochyta pisi

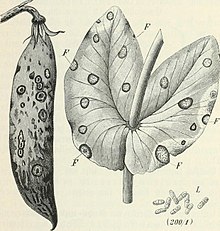

Ascochyta pisi is a fungal plant pathogen that causes ascochyta blight on pea, causing lesions of stems, leaves, and pods. These same symptoms can also be caused by Ascochyta pinodes, and the two fungi are not easily distinguishable.[1] Hosts and symptomsThe host of Ascochyta pisi is the field pea (Pisum sativum L.). Ascochyta pisi also infects 20 genera of plants and more than 50 plant species including soybean, sweet pea, lentil, alfalfa, common bean, clover, black-eyed-pea, and broad bean.[2] Field pea is an annual, cool season legume that is native to northwest and southwest Asia. Ascochyta blight of peas is one of the most important diseases of pea in terms of acreage affected. Yield losses of 5 to 15% are common during wet conditions.[2] Symptoms include:

Disease cycleAscochyta blight of peas is caused by a fungus. More than one fungal species can cause this disease.[2] Other pathogens that cause Ascochyta blight, besides Ascochyta pisi, include: Mycosphaerella pinodes, Phoma medicaginis var. pinodella, and Phoma koolunga.[4] Mycosphaerella pinodes is the only species that develops a sexual spore stage on infected residue. This stage results in the production of wind-blown ascospores.[3] Ascospores can be dispersed several kilometers. Ascospore release begins in the spring and can continue into the summer if there is enough moisture.[3] Didymella pisi is the teliomorph stage of Ascochyta pisi [2] All above ground parts of the pea plant and all growth stages are susceptible to Ascochyta pisi.[2] The fungus overwinters in seed, soil, or infected crop residues. Infected crop residue is the primary source of infection in the main pea producing areas.[3] The fungus survives on seeds and in the soil as resting spores, called chlamydospores.[5] The seed to seedling transmission rate is low.[2] Infected seeds turn purplish-brown and are often shriveled and smaller in size [6] The pathogen survives as hyphae in the seed coat and embryo.[6] New disease is established when spores of the fungus are carried to a new, healthy crop by wind or rain splash. These fungal spores then penetrate the leaf.[4] In the spring, it produces conidia in pycnidia.[3] The release of these spores begins in spring and can continue into the summer if moist conditions persist. The conidia are spread short distances by wind and rain.[5] Disease can also be established by planting infected seed.[4] Symptoms appear within 2–4 days after initial infection.[3] The Ascochyta pisi spores are viable on crop debris, although they do not survive for more than a year. Other Ascochyta blight pathogens have thick walled chlamydospores, which can survive for up to a few years in the soil.[5] Management

Before planting, some recommended management practices include destroying infected crop residues, crop rotation, and planting the current crop far from the previously infected crops' field or residues. Disease can be managed in multiple ways during and after planting. One method to manage disease is to follow the recommended seeding dates and rates to avoid fostering an ideal environment for the pathogen. If the seed density is too high and planted too early, there is increased exposure to the plant pathogen. This seeding practice also creates an ideal environment for the pathogen because the plants often produce larger canopies and experience more lodging, which creates a close, high-humidity environment ideal for the pathogen.[5] Long term crop rotation with non-host crops is recommended. Chemical control with fungicidal seed dressings is another effective method of control.[4] EnvironmentThis pathogen needs cool, moist conditions, and development occurs more quickly as plant tissues age. An increase in severity of infection is often noted when the crop canopy closes due to the dense growth that prevents dry air from penetrating the canopy. This creates a cool, humid, moist environment under the canopy, and as a result, the disease symptoms are most prevalent at the base of the canopy and spread up the plant.[5] Plant lodging also creates a dense, humid environment favorable for the pathogen. The optimal temperature for disease establishment and development is around 20 °C. Spore dispersal and the development of the disease are slowed in the absence of high levels of moisture.[3] See alsoReferences

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||