|

Architecture of Lhasa

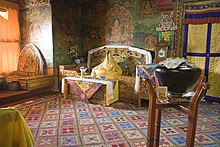

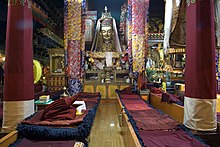

Lhasa is noted for its historic buildings and structures related to Tibetan Buddhism. Several major architectural works have been included as UNESCO's World Heritage Sites.  Potala PalaceThe Potala Palace, named after Mount Potala, the abode of Chenresig or Avalokiteśvara,[1] was the chief residence of the Dalai Lama. After the 14th Dalai Lama fled to India during the 1959 Tibetan uprising, the government converted the palace into a museum. The building measures 400 metres east-west and 350 metres north-south, with sloping stone walls averaging 3 m. thick, and 5 m. (more than 16 ft) thick at the base, and with copper poured into the foundations to help proof it against earthquakes.[2] Thirteen stories of buildings – containing over 1,000 rooms, 10,000 shrines and about 200,000 statues – soar 117 metres (384 ft) on top of Marpo Ri, the "Red Hill", rising more than 300 m (about 1,000 ft) in total above the valley floor.[3] Tradition has it that the three main hills of Lhasa represent the "Three Protectors of Tibet." Chokpori, just to the south of the Potala, is the soul-mountain (bla-ri) of Vajrapani, Pongwari that of Manjushri, and Marpori, the hill on which the Potala stands, represents Chenresig or Avalokiteshvara.[4]  The site was used as a meditation retreat by King Songtsen Gampo, who in 637 built the first palace there in order to greet his bride Princess Wencheng of the Tang dynasty of China. Lozang Gyatso, the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, started the construction of the Potala Palace in 1645[5] after one of his spiritual advisers, Konchog Chophel (d. 1646), pointed out that the site was ideal as a seat of government, situated as it is between Drepung and Sera monasteries and the old city of Lhasa.[6] Construction lasted until 1694,[7] some twelve years after his death. The palace underwent restoration works between 1989 and 1994, costing RMB55 million (US$6.875 million) and was inscribed to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1994. In 2000 and 2001, Jokhang Temple and Norbulingka were added to the list as extensions to the sites. Rapid modernisation has been a concern for UNESCO, however, which expressed concern over the building of modern structures immediately around the palace which threaten the palace's unique atmosphere.[8] The Chinese government responded by enacting a rule barring the building of any structure taller than 21 metres in the area.  The White Palace or Potrang Karpo is the part of the Potala Palace that makes up the living quarters of the Dalai Lama. The first White Palace was built during the lifetime of the Fifth Dalai Lama and he and his government moved into it in 1649.[6] It then was extended to its size today by the thirteenth Dalai Lama in the early twentieth century. The palace was for secular uses and contained the living quarters, offices, the seminary and the printing house. A central, yellow-painted courtyard known as a Deyangshar separates the living quarters of the Lama and his monks with the Red Palace, the other side of the sacred Potala, which is completely devoted to religious study and prayer. It contains the sacred gold stupas—the tombs of eight Dalai Lamas—the monks' assembly hall, numerous chapels and shrines, and libraries for the important Buddhist scriptures, the Kangyur in 108 volumes and the Tengyur with 225. The Red Palace or Potrang Marpo is part of the Potala Palace that is completely devoted to religious study and Buddhist prayer. It consists of a complicated layout of many different halls, chapels and libraries on many different levels with a complex array of smaller galleries and winding passages: The main central hall of the Red Palace is the Great West Hall which consists of four great chapels that proclaim the glory and power of the builder of the Potala, the Fifth Dalai Lama. The hall is noted for its fine murals reminiscent of Persian miniatures, depicting events in the fifth Dalai Lama's life. The famous scene of his visit to Emperor Shun Zhi in Beijing is located on the east wall outside the entrance. Special cloth from Bhutan wraps the Hall's numerous columns and pillars. On the north side of this hall in the Red Palace is the holiest shrine of the Potala. A large blue and gold inscription over the door was written by the 19th century Tongzhi Emperor of China. proclaiming Buddhism a Blessed Field of Wonderful Fruit. On the floor below, a low, dark passage leads into the Dharma Cave where Songtsen Gampo is believed to have studied Buddhism. In the holy cave are images of Songtsen Gampo, his wives, his chief minister and Sambhota, the scholar who developed Tibetan writing in the company of his many divinities. The tomb of the 13th Dalai Lama is located west of the Great West Hall and it can only be reached from an upper floor and with the company of a monk or a guide of the Potala. Built in 1933, the giant stupa contains priceless jewels and one ton of solid gold. It is 14 metres (46 ft) high. Devotional offerings include elephant tusks from India, porcelain lions and vases and a pagoda made from over 200,000 pearls. Elaborate murals in traditional Tibetan styles depict many events of the life of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama during the early 20th century. Norbulingka The Norbulingka palace and surrounding park is situated in the west side of Lhasa, a short distance to the southwest of Potala Palace and with an area of around 36 hectares (89 acres), it is considered to be the largest man made garden in Tibet.[9][10] It was built from 1755.[11] and served as the traditional summer residence of the successive Dalai Lamas until the 14th's self-imposed exile. Norbulingka was declared a ‘National Important Cultural Relic Unit”, in 1988 by the State council. In 2001, the Central Committee of the Chinese Government in its 4th Tibet Session resolved to restore the complex to its original glory. Grant funds to the extent of 67.4 million Yuan (US$8.14 million) were sanctioned in 2002 by the Central Government for the restoration works; the restoration works taken up from 2003 mainly covered the Kelsang Phodron Palace, the Kashak Cabinet offices and many other structures.  The summer residence of the Dalai Lama is now a tourist attraction. The palace has a large collection of Italian chandeliers, Ajanta frescoes, Tibetan carpets and many other artifacts. Murals of Buddha and the 5th Dalai Lama are seen in some rooms. The 14th Dalai Lama’s (who fled from Tibet and took asylum in India) meditation room, bedroom, conference room and bathroom are part of the display explained to the tourists.[12] The Sho Dun Festival (popularly known as the "yogurt festival") is an annual festival held at Norbulingka during the seventh Tibetan month in the first seven days of the Full Moon period, which corresponds to dates in July/August according to the Gregorian calendar. The week-long festivities are marked by eating and drinking, with Ache Lhamo, the Tibetan opera performances as the highlight, held in the park and other venues in the city. On this occasion yak races are a special attraction held in the Lhasa stadium. During this festival, famed opera troupes from different regions of Tibet perform at the Narubulingka grounds; the first opera troupe was founded in the 15th century by Tangtong Gyelpo (considered the Leonardo da Vinci of Tibet). Over the centuries other opera formats of the 'White Masked Sect' and the "innovative" 'Black Masked Sect' added to the repertoire, and all these forms and subsequent innovations are enacted at the Sho Dun festival.[13][14][15] Barkhor The Barkhor is an area of narrow streets and a public square in the old part of the city located around Jokhang Temple and was the most popular devotional circumambulation for pilgrims and locals. The walk was about one kilometre long and encircled the entire Jokhang, the former seat of the State Oracle in Lhasa called the Muru Nyingba Monastery, and a number of nobles' houses including Tromzikhang and Jamkhang. There were four large incense burners (sangkangs) in the four cardinal directions, with incense burning constantly, to please the gods protecting the Jokhang.[16] Most of the old streets and buildings have been demolished in recent times and replaced with wider streets and new buildings. Some buildings in the Barkhor were damaged in the 2008 unrest.[17] Jokhang   The Jokhang is located on Barkhor Square in the old town section of Lhasa. It was founded around 642 during the reign of king Songtsen Gampo (605?–650 CE) to celebrate his marriage with Chinese Tang dynasty Princess Wencheng.[18] For most Tibetans it is the most sacred and important temple in Tibet. It is in some regards pan-sectarian, but is presently controlled by the Gelug school. Along with the Potala Palace, it is probably the most popular tourist attraction in Lhasa. It is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site "Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace," and a spiritual centre of Lhasa. This temple has remained a key center of Buddhist pilgrimage for centuries. The circumambulation route is known as the "kora" in Tibetan and is marked by four large stone incense burners placed at the corners of the temple complex. After circumambulating the exterior, pilgrims make their way to the main hall of the temple which houses the Jowo Shakyamuni Buddha statue, perhaps the single most venerated object in Tibetan Buddhism. There are also famous statues of Chenresig, Padmasambhava and King Songtsen Gampo and his two foreign brides, Princess Wencheng (niece of Emperor Taizong of Tang) and Princess Bhrikuti of Nepal. Jokhang was sacked several times by the Mongols, but the building survived. In the past several centuries the temple complex was expanded and now covers an area of about 25,000 sq. meters [2] The Jokhang temple is a four-story construction, with roofs covered with gilded bronze tiles. The architectural style is based on the Indian vihara design, and was later extended resulting in a blend of Nepalese and Tang dynasty styles. The rooftop statues of two golden deer flanking a Dharma wheel is iconic. Jokhang's interior is a dark and atmospheric labyrinth of chapels dedicated to various gods and bodhisattvas, illuminated by votive candles and thick with the smoke of incense. Although some of the temple has been rebuilt, original elements remain: the wooden beams and rafters have been shown by carbon dating to be original; the Newari door frames, columns and finials date from the 7th and 8th centuries.[3] The Jokhang owns a large and very important collection of about eight hundred metal sculptures, in addition to thousands of painted scrolls known as thangkas. The statues are hidden away in temples closed to the public and access is almost impossible. During numerous visits to the Jokhang between 1980 and 1996, Ulrich von Schroeder managed to take photographs of about five hundred metal statues of interest. Among them are some extremely rare and important brass and copper statues originating from Kashmir, Northern India, Nepal, Tibet, and China. However, the most important statues of the Jokhang collection are those that date back to the Yar lung dynasty (7th–9th century).[19] Tromzikhang Tromzikhang is a historic building located northwest of Jokhang which originally dated to around 1700 and was once a government building for officials such as the Ambans, representatives of the Qing emperor.[20] It was demolished in the 1990s except for the magnificent facade. Today Tromzikhang is a notable market in Lhasa and a housing complex. Between 1938 and 1949, Tromzikhang was used as a Republican School, with a staff of Han, Hui and Tibetan teachers. It was built primarily for the local Han population of merchants with a number of staff from the Chinese Mission.[21] Phuntsok Wangyal, a progressive pro-Communist Tibetan from Batang who founded the Tibetan Communist Party, also taught there for some time.[21] The school taught pupils such as Gyalo Dondrup, the eldest brother of the 14th Dalai Lama as well as Nepalese and Muslim minorities living in Lhasa.[21] The school was closed down in 1949 when the Chinese Mission was expelled from Tibet.[21] The building is characterized by its length; it has a 63-metre (207 ft) facade.[22] Architecturally it combines stylistic elements of monasteries and noble houses being symmetrical along a central axis, and hierarchical from down to up with large balconies and lavishly decorated interiors on the uppermost floor.[22] Today Tromzikhang market sells items such as yak butter, cheese, tea, noodles, vegetables and candy. Nearby is Tromzikhang Bus Station and a mosque and a small 15th century building housing a two-story image of the Maitreya, named the Jamkhang.[20] Muru Nyingba Monastery Muru Nyingba Monastery or Meru Nyingba is a small Buddhist monastery located behind Jokhang and Barkhor. It was the Lhasa seat of the former State Oracle who had his main residence at Nechung Monastery.[23] It is said that Emperor Songtsän Gampo built the first building here and it is where the great Tibetan scholar, Thonmi Sambhota, completed his work developing the Tibetan alphabet in the first half of the 7th century. The present building, first constructed during the reign of King Ralpacan (c. 806–838 CE),[24] is built like an Indian vihara around a courtyard, with the lhakang ('temple', literally 'residence of the deity') to the north and monks quarters on the three other sides. The lhakang contains a number of fine murals – the central image being that of Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava), with images of the five Nyingma Yidam-Protectors and Tseumar and Tamdrin in glass cases around the walls. The Dhukang or Assembly Hall of Muru Nyingba is a very active temple, built in the 19th century by Nechung Khenpo Sakya Ngape, and renovated in 1986. There are frescoes portraying the protector deity Dorje Drakden, Tsongkhapa, Atisha, Padmasambhava, Shantarakshita, and King Trisong Detsen. The central image of Avalokiteshvara is new with a copper Padmasambhava to the right and a sand mandala to the left. Behind is an inner sanctum with more images and upstairs is the Tsepame Lhakang with 1,000 small images of Amitayas (or Amitābha) Buddha.[25] The Lhasa Zhol PillarThe graceful Lhasa Zhol Pillar, below the Potala, dates as far back as circa 764 CE.[26] and is inscribed with what may be the oldest known example of Tibetan writing.[27] The pillar contains dedications to a famous Tibetan general and gives an account of his services to the king including campaigns against China which culminated in the brief capture of the Chinese capital Chang'an (modern Xi'an) in 763 CE[28] during which the Tibetans temporarily installed as Emperor a relative of Princess Jincheng Gongzhu (Kim-sheng Kong co), the Chinese wife of Trisong Detsen's father, Me Agtsom.[29][30] Ramoche Temple  Ramoche Temple is considered the most important temple in Lhasa after the Jokhang Temple. Situated in the northwest of the city, it is east of the Potala and north of the Jokhang,[31] covering a total area of 4,000 square meters (almost one acre). Ramoche is considered to be the sister temple to the Jokhang which was completed about the same time. Tradition says that it was built originally to house the much revered Jowo Rinpoche statue, carried to Lhasa via Lhagang in a wooden cart, brought to Tibet when Princess Wencheng came to Lhasa. Unlike, the Jokhang, Ramoche was originally built in the Chinese style. During Mangsong Mangtsen's reign (649–676), because of a threat that the Tang Chinese might invade, Princess Wen Cheng is said to have had the statue of Jowo Rinpoche hidden in a secret chamber in the Jokhang. Princess Jincheng, sometime after 710 CE, had it placed in the central chapel of the Jokhang. It was replaced at Ramoche by a statue of Jowo Mikyo Dorje, a small bronze statue of the Buddha when he was eight years old, crafted by Vishvakarman, and brought to Lhasa by the Nepalese queen, Bhrikuti.[32][33] The temple was badly damaged during the Mongol invasions and there is no certainty that the statue that remained in 1959 was the original one. The original temple was destroyed by fire, and the present three-storied building was constructed in 1474. Soon after it became the Assembly Hall of the Gyuto Tratsang, or Upper Tantric College of Lhasa and was home to 500 monks. There was a close connection with Yerpa which provided summer quarters for the monks.[33][34] The temple was gutted and partially destroyed in the 1960s and the bronze statue disappeared. In 1983 the lower part of it was said to have been found in a Lhasa rubbish tip, and the upper half in Beijing. They have now been joined and the statue is housed in the Ramoche Temple, which was partially restored in 1986,[31] and still showed severe damage in 1993. Following the major restoration of 1986, the main building in the temple now has three stories. The first story includes an atrium, a scripture hall, and a Buddha palace with winding corridors. the second floor is mainly residential but has a chapel with an image of Buddha as King of the Nāgas. The third story contained the bedroom and chapel once reserved for Dalai Lama[35] Upon entering the main building, one can see the ten large fluted pillars holding some of the remaining Tibetan relics such as the encased lotus flowers, coiling cloud, jewelry, and particular Tibetan characters. The golden peak of the temple with the Han-style upturned eave can be seen from any direction in Lhasa city. The temple is an interesting example of the combination of Han and Tibetan architectural styles. Today it is an important repository of Tibetan artifacts. Lingkhor Lingkhor is a sacred path, most commonly used to name the outer pilgrim road in Lhasa matching its inner twin, Barkhor. The Lingkhor in Lhasa was 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) long enclosing Old Lhasa, the Potala and Chokpori hill. In former times it was crowded with men and women covering its length in prostrations, beggars and pilgrims approaching the city for the first time. The road passed through willow-shaded parks where the Tibetans used to picnic in summer and watch open air operas on festival days. New Lhasa has obliterated most of Lingkhor, but one stretch still remains west of Chokpori. Chagpori Chagpori, meaning 'Iron Mountain', is a sacred hill, located south of the Potala. It is considered to be one of the four holy mountains of central Tibet and along with two other hills in Lhasa represent the "Three Protectors of Tibet.", Chagpori (Vajrapani), Pongwari (Manjushri), and Marpori (Chenresig or Avalokiteshvara).[4] It was the site of the most famous medical school Tibet, known as the Mentsikhang, which was founded in 1413. It was conceived of by Lobsang Gyatso, the "Great" 5th Dalai Lama, and completed by the Regent Sangye Gyatso (Sangs-rgyas rgya-mtsho)[36] shortly before 1697. The medical school and a temple housing priceless statutes of coral (Tsepame), mother-of-pearl (of Tujechempo) and turquoise (of Drolma) were completely demolished by PLA artillery in 1959 after the Lhasa uprising.[36] It is now crowned by unsightly radio antennas.[37][38] Tibet MuseumThe Tibet Museum in Lhasa is the official museum of the Tibet Autonomous Region and was inaugurated on October 5, 1999. It is the first large-sized modern museum in the Tibet Autonomous Region and has a permanent collection of around 1000 artefacts, from examples of Tibetan art to architectural design throughout history such as Tibetan doors and beams.[39][40] It is located in an L-shaped building, located directly below the Potala Palace on the corner of Norbulingkha Road. The modern museum building fuses together traditional Tibetan architecture with the modern.[41] It is a grey brick building with dark brown and white roof furnishings with a golden orange gilded roof. The museum is structured into three main sections: a main exhibition hall, a folk cultural garden and an administrative quarter.[39] The central courtyard to the museum is uniquely designed, with a white, sleek looking floor, and drawing upon traditional monastic conventions. It features an origin, black and white design in the centre and has lighting through large skylight windows above. The museum covers an area of 53,959 square meters, with a total construction area of 23,508 square meters.[39] The area for the exhibition department covers 10,451 square meters.[39] The History of Tibetan Culture Exhibition is divided into pre-history culture, indivisible history, culture and arts, and people's customs, exploring several thousand years of Tibetan history, politics, religion, cultural arts, and customs.[40] Items include Tibetan-script books, documents and scrolls, the arts of Tibetan theatre, Tibetan musical instruments, Tibetan medicine, Tibetan astronomy and calendar reckoning (including charts),[42] Tibetan sculpture, and thangka painting and arts.[40] The exhibited artefacts are protected by the Tibetan Autonomous Region Cultural Relics Protection Organization given the uniqueness and cultural value of some of the items.[40] There are numerous statues of buddhas, bodhisattvas, and figures, masks, rare sutras written on pattra leaves and birch bars, and manuscripts written with gold, silver and coral powder.[39] There are many items of Tibetan handicrafts, and invaluable jewellery such as gold, silver and jade items.[39] Potala Square and Anniversary Monument The Monument to the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet was unveiled on the Potala Square on May 23, 2002 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Seventeen Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet, and the work in the development of the autonomous region since then. The 37-metre-high monument is shaped as an abstract Mount Everest and is engraved with the calligraphy of its name by Chinese Communist Party general secretary Jiang Zemin, with an inscription describing the socioeconomic development experienced in Tibet in the past fifty years.[43] Footnotes

External links |