|

Annexation of Savoy

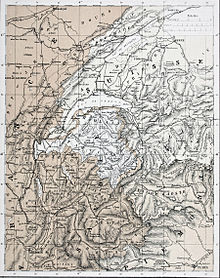

The term annexation of Savoy to France is used to describe the union of all of Savoy—including the future departments of Savoy and Haute-Savoie, which corresponded to the eponymous duchy—and the County of Nice, which was then an integral part of the Kingdom of Sardinia, with France (Second Empire) in 1860. This union is expressed in the French version of the Treaty of Turin. Despite the country's history of occupation and annexation by various powers, including the French (from 1536 to 1559, from 1600 to 1601, 1689, and then from 1703 to 1713) and the Spaniards (from 1742 to 1748), the expression in question pertains to the "union" clause outlined in Article 1 of the Treaty of Turin of March 24, 1860. This clause concerns the joint rule of France and the Savoy during the Carolingian Empire. The expression is also used about the "union" clause in Article 1 of the Treaty of Turin of March 24, 1860,[Note 1] which pertains to the historical fact that France and Savoy had been jointly ruled during the Carolingian Empire. This occurred on seven occasions: first, from 749; then, by France during the Revolution from 1792 to 1814; and finally, on five occasions by France between 1860 and 1947. TerminologyUse of termsThe terminology employed to designate this period is variable, and four terms have become established in usage: "annexation," "union," "cession," and "attachment." The words "annexation" and "union," preferred to "cession," were used during the 1860 debates by both supporters and opponents of union with the French Empire.[1] However, the term "union" appears in the text of the 1860 treaty.[1] "Article One – His Majesty the King of Sardinia consents to the union of Savoy and the arrondissement of Nice." Indeed, it gives the impression that the populations consent to the decisions of the princes. Professor Luc Monnier, in his book L'Annexion de la Savoie à la France et la politique suisse (1932), notes: "They did not speak of annexing Nice and Savoy, but of consulting the wishes of these two provinces, a more elegant formula that respected propriety." Moreover, Count Cavour seems to have insisted on using the word "union" instead of "cession".[1] The acceptance by the populations of this cession will be highlighted with the results of the April 1860 plebiscite, which marked the definition of the term in 19th-century Larousse: "the acquisition of a territory, a country, with the formally expressed adherence of the populations of that territory, that country".[2][1] The expression is frequently written with a capital "A", particularly in certain works. In his book, Histoire de la Savoie en images: images & récits, Christian Sorrel discusses using the capitalized "A" in the context of the region's history. He notes that the history of Savoy, on a large scale, is not exempt from these tensions, as evidenced by the ongoing debates surrounding the millennium of the dynasty, the Revolution, the Annexation, and the Resistance. These words, when capitalized, convey a sense of timelessness, stimulate the imagination, and rekindle passions, which can sometimes be contrived.[3] The term "union" was also employed during the fiftieth anniversary in 1910. However, during the centennial celebration in 1960, official documents used the term "attachment", which persists during the sesquicentennial celebrations.[1][4][5][6] Historians specializing in the theme from the Savoyard school of thought, such as Professors Jacques Lovie and Paul Guichonnet, employ the term "annexation." Italian authors, on the other hand, tend to use the term "cessione" ("cession"), which aligns more closely with the legal reality of the situation.[1] Local usagesThe principal urban centers of Savoy have a thoroughfare designated as "Annexation Street." However, the designation is considerably more prevalent in the northern reaches of the region[Note 2] than in the south, where Chambéry, the erstwhile capital of the duchy, has renamed it "General-de-Gaulle Avenue".[7] HistoryPrelude: a secret agreement On July 21, 1858, Emperor Napoleon III and Camille Benso, Count of Cavour, President of the Council of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, convened in secret at Plombières to deliberate the prospect of providing military and diplomatic assistance to the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia in its conflict with the Austrian Empire. In return, they proposed the transfer of the Savoyard and Niçois territories to France. Subsequently, a treaty was signed in Turin on January 26, 1859, to formalize the Franco-Piedmontese alliance by Prince Napoleon Jérôme, who married Princess Clotilde of Savoy four days later. However, on July 7, 1859, following the armistice of Villafranca, Napoleon III renounced Savoy, citing the failure to achieve the desired military objectives.[8] In their departure, the Savoyard population[9] greeted the French troops with enthusiasm for their support of the Italian cause. Witnessing the unraveling of his plans, Cavour was compelled to relinquish power, paving the way for the unpopular Urbano Rattazzi. Debates on union with France From August 1859 to January 1860, Savoy was beset by uncertainty regarding its future. In response, liberals mobilized in favor of Savoy's attachment to their sovereigns. Concurrently, a pro-French annexationist party emerged, while in the north of the duchy, the idea of attachment to Switzerland arose. On July 25, 1859, approximately twenty-five or thirty Savoyard individuals, lacking notable political or economic influence, primarily from Chambéry, led by Dr. Gaspard Dénarié and lawyer Charles Bertier,[10] editor-in-chief of the conservative newspaper Courrier des Alpes, presented an address to King Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy, requesting his consideration of the desires of the ducal province.

The question words affirm a "Savoyard nationality," as the Revue des deux Mondes reported.[12] This address was the subject of a petition throughout Savoy, marking the beginning of an opinion movement across the country, notably through the Savoyard, Turin, Geneva, and French press. In the days that followed, on July 28, 1859, in Annecy, a group of approximately a dozen Savoyard deputies, all of whom identified as conservative Catholics, petitioned the government to address the material fate of the province of Savoy.[13] The government of Urbano Rattazzi sought to mitigate the impact of the Courrier des Alpes by suspending its publication on August 3, 1859.[14] This was in response to the newspaper's call for the residents of Savoy to be granted the same nationality voting rights as those in central Italy. Following a period of suspension, the publication resumed on December 1.  In August 1859, Count Cavour, who was on a period of rest in Switzerland, returned to the Kingdom of Sardinia via Savoy. He seized the opportunity to engage with prominent figures such as General Intendant Pietro Magenta,[Note 3] a democrat who had held the office in Chambéry since 1856 and was disliked by conservatives,[15] as well as anti-annexationists François Buloz, co-founder of the Revue des deux Mondes, and the liberal Albert Blanc, who published La Savoie et la Monarchie constitutionnelle. This visit was followed by that of the king's two young sons, but the reception remained polite, as noted by historians of the period, such as Henri Menabrea. However, the Revue des Deux Mondes, which was anti-annexationist, indicated that the reception given to these young princes had not been as cold as had been claimed, especially in the ultramontane papers of France. Mr. Albert Blanc had refuted this allegation in writing in which he had reduced the separatist movement of Savoy to its proper value.[16] In the period between December 1859 and January 1860, the government dispatched clandestine emissaries to ascertain the prevailing sentiment among the Savoyard populace regarding the proposed union with the French Empire. "All evidence leads to the conclusion that the Piedmontese regime is profoundly unpopular among the elites, the Church and the general population. The prospect of joining France, a prosperous and powerful country, represents a significant temptation for the Savoyards."[17] In Turin, Count Cavour returned to power on January 16, 1860, after six months of withdrawal, assuming the role of President of the Council. He was prepared to pursue the unification of Italy: "My task is more arduous and challenging than it was in the past. The objective of uniting the disparate elements that constitute Italy, of harmonizing the disparate regions of the country, presents as many difficulties as a war with Austria and the struggle for Rome."[18] The Swiss optionIn February and March, petitions were circulated in the communes of Chablais and Faucigny,[19] advocating for union with the Swiss Confederation. The petition stated: "A period of union with France spanned several years, and many still evoke a sense of nostalgia when contemplating that era. Since 1848, we have been closely allied with Piedmont. Nevertheless, despite our sympathies for either free Italy or France, other, more profound sympathies lead us to conclude that annexation to Switzerland is the optimal course of action. Indeed, such is our most fervent aspiration, rooted in our exclusive ties with Geneva, our commercial interests, and the myriad advantages that elude us elsewhere." This petition garnered 13,651 signatures across 60 communes of Faucigny, 23 of Chablais, and 13 surrounding Saint-Julien-en-Genevois (cited by Paul Guichonnet).[Note 4][20] Those who advocated this solution included the attorneys Edgar Clerc-Biron and Joseph Bard,[Note 5] representing Bonneville, and Henri Faurax, representing Saint-Julien, as well as the surveyor Adolphe Bétemps, representing Thonon.[21] Additionally, the idea was advanced in the Turin Chamber by the deputy Joseph-Agricola Chenal.[Note 6] However, the matter did not persist for an extended period. A limited number of newspapers outside the province disseminated the information. The Journal de Genève published the petition, and the Parisian newspaper La Patrie participated in the discourse by publishing a motion from Savoyards residing in the northern region of the duchy. The reaction of conservatives in favor of maintaining Savoyard unity was prompt, invoking the historical precedent of Bernese domination during the 16th century. The prospect of a split of Northern Savoy prompted a response from some notable figures, including fifteen personalities from Chambéry. These included lawyer Charles Bertier, Dr. Gaspard Dénarié, Amédée Greyfié de Bellecombe, and deputies Gustave de Martinel, Timoléon Chapperon, and Louis Girod. De Montfalcon, among others, was supported by approximately forty individuals who published a Déclaration on February 15, 1860, denouncing the potential division of Savoy as a violation of its historical and cultural identity. They asserted that such a move would be detrimental to the region's pride and sense of national identity, and would be perceived as an insult to the deeply held values and aspirations of the Savoyard people. They would denounce any proposal for the fragmentation or division of the ancient Savoyard unity as a crime against the fatherland.[22] Some of the signatories were present during the meeting with the Tuileries delegation. On February 26, 1860, the French government rejected the notion of an autonomous Savoy.  On March 1, 1860, Napoleon III proclaimed to the Legislative Body his intention to claim the gratuity agreed upon at Plombières, namely, the western slope of the Alps mountains,[23] comprising Nice and Savoy, in exchange for his support for Italian unity. On March 8, 1860, the divisional councils, convened in Chambéry, articulated a preference for the preservation of Savoy's territorial integrity, thereby rejecting the proposed partition of Savoy between Switzerland and France. The treaty and the plebiscite On March 12, 1860, a clandestine preliminary convention was concluded in Turin, whereby the cession of Savoy and Nice to France was acknowledged. The principle of consulting the population was accepted. The duchy's divisional councils convened and resolved to dispatch a delegation of 41 Savoyards (nobles, bourgeois, and ministerial officers) in favor of annexation.[Note 7] This delegation was to be led by Count Amédée Greyfié de Bellecombe[24] and would receive a solemn reception at the Tuileries from the Emperor on March 21, 1860. On March 24, 1860, the signing and later publication of the Treaty of Annexation, also known as the Treaty of Turin, occurred. The initial three articles delineated the stipulations of this annexation. Primarily, the term "annexation" was not employed; instead, the document referred to a "union" (Article I). Consequently, the call for the consent of the Savoyards and the organization of a plebiscite was made. Secondly, the zone of Northern Savoy, which had been previously neutralized, was guaranteed. The zone of Northern Savoy, guaranteed by the Treaty of Turin of 1816, was maintained (art. II). Finally, a mixed commission was established to determine the borders of the two states, considering the configuration of the mountains and the necessity of defense (art. III). In April 1860, French senator Armand Laity (from April 4 to 28) commenced preparations for the plebiscite.[25] French emissaries traversed the regions of Chablais and Faucigny to ascertain the sentiments of the local populations. Concurrently, the advantages of annexation were espoused, including the abridgment of military service, the dissolution of customs with France, the influx of inexpensive commodities, the influx of capital, the more equitable distribution of taxation, and, most significantly, the unification of a nation with a common linguistic heritage for the Savoyards. On March 28, 1860, French troops arrived in Chambéry.[Note 8]  The plebiscite was conducted on April 22 and 23, 1860. It was the inaugural universal suffrage election in Savoy,[17] and voters were tasked with answering the question, "Does Savoy desire reunification with France?" As a historian elucidates, for Napoleon III, the objective was not to ascertain the citizens' opinion but to demonstrate that his policy enjoyed popular support. "Every effort was made to ensure that the vote results would align with the Emperor's expectations."[17] The voting conditions would not be considered completely democratic in the present era. The ballot boxes were in the hands of the same authorities who had issued the proclamations. "Controls were impossible",[Note 9] observed one historian. Churches held masses and sang "Domine salvum fac Imperatorem" (Lord, save the emperor).[Note 10] Notwithstanding considerable conservative exertions, the historian Paul Guichonnet posited that the annexation was "primarily the work of the clergy."[26] Dr. Truchet of Annecy posited that had the six hundred Savoyard priests opposed the annexation, the result would have been near unanimous support for the measure.[26] Guichonnet observed that the Savoyard clergy exhibited a stance that was "antithetical to Cavour's secular and pro-Italian orientation, espoused by the aristocracy and clergy, and guiding the politically uneducated rural masses."[27] On April 29, the Court of Appeal of Savoy (Chambéry) formally announced the results of the plebiscite.

In most polling stations, there were no ballots marked "no."[28] On April 28, 1860, the correspondent in Geneva for the British newspaper The Times described the referendum as "the greatest farce ever played in the history of nations."[28] Contemporary scholars have posited that "a truly democratic vote would have yielded the same result, with perhaps less glorious but much more credible figures."[29] On May 29, 1860, the Turin chamber ratified the treaty of cession of March 24 by a vote of 229 in favor, 33 against, with 25 abstentions, and the Senate by a vote of 92 in favor, 10 against.[30] On June 12, France ratified the treaty, and on June 14, 1860, it officially assumed control of the territory following the treaty signing.[31] The following day, an imperial decree established the two departments of Savoy and Haute-Savoie. Swiss supporters On March 28, 1860, an armed delegation from Switzerland, led by the secretary of the foreign office, Jules-César Ducommun, and composed of French anti-Bonapartist refugees, departed from Geneva to join the town of Bonneville. The delegation, which had assumed the guise of Northern Savoyards, supporters of annexation to Switzerland, attempted to galvanize the inhabitants by proclaiming, "Let us extend our arms to this Swiss homeland that our ancestors dreamed of and that must bring us well-being and freedom. Long live Switzerland, our new homeland. Long live the Federal Constitution proclaimed this day in Northern Savoy as the only fundamental law of the country."[32]  In Bonneville, the elections for the Turin parliament resulted in a resounding victory for the pro-French deputies. In response, the furious inhabitants hastily removed the Swiss flags and posters erected by the refugees. Consequently, the city authorities, seeking to circumvent a potential scandal, promptly invited the Genevans to return home at their earliest convenience.[33]  On the following day, March 29, 1860, the radical Geneva deputy John Perrier, who was known as Perrier-le-Rouge and had previously worked as a goldsmith, accompanied by an armed Swiss delegation, went to Thonon-les-Bains intending to incite an uprising. However, upon their arrival, they were met with insults and jeers from the local inhabitants. They sought refuge in Évian-les-Bains but were subsequently expelled and removed from the premises aboard the vessel designated "Italy," which was bound for Lausanne. The authorities of Chambéry and Annecy denounced the "maneuvers of all kinds in the city of Geneva and outside, aimed at detaching the provinces of Chablais, Faucigny, and even part of Annecy from the old Savoyard family."[32] Upon his return to Switzerland, John Perrier was arrested. He was imprisoned in Geneva for 67 days before being released without conviction.[34] Savoy under the Second Empire

To commemorate the event, a series of traditional celebrations were held in the rural and urban communities of Savoy over several days. From August 27 to September 5, the French emperor, accompanied by Empress Eugénie, undertook a triumphant journey through the recently annexed French province.[36] The imperial couple was greeted in Chambéry, Annecy, Thonon, Chamonix, Évian-les-Bains, Sallanches, Aix-les-Bains, and Bonneville with military parades, regional costume parades, organized balls, and lake promenades. On September 3, 1860, the Empress proceeded to the Bossons glacier and the Montenvers passed on a mule, subsequently continuing to the Mer de Glace.[37] The new administrationThe Savoyard province was subdivided into two departments, each comprising multiple districts. In 1860, the province population was 542,535, with 267,496 residing in Haute-Savoie and 275,039 in Savoy.

Hippolyte Dieu, who had previously served as secretary of the provisional government of 1848 and as the inaugural prefect of the Savoy region, was the prefect of Chambéry. He was responsible for managing the financial affairs of the two departments. He was a pragmatic individual who directed that circulars be sent to the municipalities to explain the new institutions before meeting with municipal councilors and implementing French laws. Gustave-Léonard Pompon-Levainville, the prefect of Haute-Savoie, promptly relinquished his post at the prefecture of Annecy to Anselme Pétetin (first class) from Haute-Savoie.[38] The new ecclesiastical organization Furthermore, the Church was obliged to comply with French ecclesiastical legislation, including the number of dioceses and the maintenance of civil status registers. On March 30, 1860, Bishop Billiet penned a missive to the emperor, in which he stated:

A transitional regime was permitted to acknowledge the legitimacy of civil marriage and the maintenance of civil status registers until the demise of the current holders. Four prelates were designated to the archdiocese of Chambéry and the bishoprics of Annecy, Moûtiers, and Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne. Bishop Alexis Billiet was elevated to the rank of Cardinal to circumvent potential disputes that might arise from the abolition of six feast days, including that of Saint Francis de Sales. At the behest of the King of Sardinia, Napoleon III consented to establish a religious office at Hautecombe Abbey, operating under the aegis of the Archdiocese of Chambéry. This tradition, initiated by Charles-Félix of Savoy, served to commemorate the princes of the erstwhile royal family of Savoy. The religion of the Order of the Consolata of Turin was supplanted by the Cistercian Order of Sénanque (Vaucluse).[40] The new military organizationThe Savoy Brigade of the Sardinian army was disbanded, and a significant number of officers opted for Piedmont. Some, who remained loyal to the Sardinian king, chose to retain their advantages and traditions. These included General Luigi Federico Menabrea and Admiral Simone Arturo Saint-Bon, who is regarded as the founder of the Italian ironclad navy.[Note 12] Those Savoyard soldiers who elected to serve in the French military were assembled in the 103rd line infantry regiment, stationed in Sathonay, near Lyon, and Châlons-sur-Marne. Some Savoyards were transferred by lottery to the 22nd military division, based in Grenoble. Of these, over 10% were draft dodgers. In contrast to the Piedmontese military service, which lasted 11 years, the French service lasted only seven years.[40] The new justiceSince the reunification of Savoy in 1860, the guillotine has been employed on only one occasion in Savoy and Haute-Savoie, with the courts increasingly favoring penal servitude for criminal cases, particularly following the enactment of the 1888 penal code. Before the annexation, the Sardinian authorities appointed magistrates aligned with their policy preferences to positions within the public prosecutors' offices and courts. Charles-Albert Millevoye, attorney general and former prosecutor of Nancy, was dispatched by the French administration to reorganize the nascent institutions. He retained the local magistrates but undertook a comprehensive reorganization of the public prosecutors' offices. With the June 12, 1860, decree, French penal and criminal procedure laws became applicable in Savoy. Before the annexation, the high jurisdiction was comprised of three chambers:

The initial configuration of the legislative body involved the consolidation of the first two chambers, resulting in a single chamber for some time. The courts of first instance were established in Chambéry, Albertville, Moûtiers, and Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne, with a single judge presiding over each district. These developments were met with resistance from the legal profession and the magistrates in place, who collectively opposed the new French institutions.[41] The Court of Appeal of Chambéry was maintained and remains the sole appellate court in France, along with the Council of state.[42] The new economic lifeIndustryBefore the annexation of 1860, the region's heavy industry was virtually non-existent. The industry typical of any mountainous province was that of Savoy, which was therefore ill-suited to large-scale industrial development. Instead, the focus was on local activities. Nevertheless, some mining areas employed approximately twenty workers each in Saint-Georges-des-Hurtières in Maurienne, Randens, Argentine, and Peisey-Macôt, with the vast majority of production being sold to Piedmont. On November 30, 1863, the Cluses watchmaking school was designated a state school by decree. Agricultural machinery and wire from Sallanches gained some reputation.[43] Industrial installations in the Faucigny province, powered by traditional hydraulic force, were listed in a survey conducted by deputy Charles-Marie-Joseph Despine (1792–1856) before his death. The survey, which was recorded and exploited in 1860, included 162 sawmills, 39 hammer mills and forges, 11 nail factories, and other similar facilities. However, wool-spinning mills were not included in the survey.[44] In the municipalities of Modane, Saint-Michel-de-Maurienne, and Bozel, the exploitation of anthracite yielded a total of over 6,000 tons of ore in 1861. The cities of Chambéry, Annecy, and Aix-les-Bains used lignite as an energy source, and over 2,300 businesses employed hydraulic energy, primarily on a private basis. Some artisanal industries were forced to cease operations, such as the 67 nail workshops in the Bauges, which employed 380 individuals and exported 140 tons of nails. Seven years later, only 18 local businesses with approximately a hundred employees remained.[40] AgricultureThe isolation and lack of capital that characterized the region of Savoy resulted in a delay in the growth of agriculture. Despite this, local competitions were organized with the support of the newspapers Le Savoyard and Le Propagateur. Over time, exchanges were established with the French market, which led to the Tarine cows gaining recognition at the Lyon exhibition in 1861 and the Moulins competition in 1862.[37] The designation of the Tarine breed, initially proposed at the Moûtiers competition in 1863, was subsequently recognized by the relevant authorities in 1864. This recognition led to an increase in the sale of this livestock, valued for its resilience and high milk production. New techniques gradually supplanted the mules of Faucigny and small farms of less than five hectares.[40] The conservation of the Waters and Forests of Chambéry and Annecy has been in effect since January 1861, with the advent of "forest ranger" officials. The cultivation of vines on small, heterogeneous plots yielded low yields, with vineyards producing fine wines such as "Roussette," "Mondeuse," or "Persan."[40] TransportThe Mont-Cenis railway tunnel was inaugurated in 1857 by King Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy. Construction was completed in 1871,[Note 13] at the advent of the Third Republic. The Mont-Cenis railway tunnel became an essential link for the transportation of goods and passengers between Italy and France, including trains carrying automobiles. Until the opening of the Fréjus road tunnel in 1982, the Mont-Cenis pass was the primary route between Savoy and Italy. Additional railway sections were constructed, connecting Grenoble to Montmélian in August 1864 and Aix-les-Bains to Annecy in July 1866. Archives During the 1860 annexation, the Sardinian government relocated many historical documents from Chambéry Castle to Turin. These included feudal titles, estate registers, and ecclesiastical inventories. Following a claim by the French government, Italy returned these documents in 1950. The archives of the former Duchy of Savoy are now stored in the departmental archives of Savoy and Haute-Savoie.[45] To demonstrate to the Parisian bourgeoisie the newly attached provinces of Savoy, Napoleon III commissioned approximately thirty color lithographs portraying the landscapes and towns of the region.[46] CelebrationsFiftieth anniversary in 1910 Festivities in the region marked the fiftieth anniversary of the annexation of Savoy.[47][48] In March, a delegation of mayors from the region of Savoy was received at the Élysée Palace at the invitation of the president of the French Republic, Armand Fallières. On September 3, he visited Savoy, accompanied by Minister of Education Gaston Doumergue and General Brun, minister of war.[47] They were greeted in Chambéry by Antoine Perrier, Vice President of the Senate and President of the General Council of Savoy, and the city's mayor, Dr. Ernest Veyrat.[48] On September 4, 1910, the president proceeded to the city of Aix-les-Bains and used the Mont-Revard cog railway.[49] He also made an excursion to Chamonix to view Mont Blanc. On April 3, 1867, the Société Philanthropique Savoisienne[50] and the Union des Allobroges held a celebratory event at the Trocadéro in Paris,[51] attended by 6,000 individuals.[52] Centenary in 1960In 1960, the centenary of the annexation was commemorated in Savoy and Paris. On this occasion, there was a notable shift in semantics, whereby the event was no longer referred to as the Annexation, but rather the Attachment. To organize the centenary of Savoy's attachment to France, the two Savoyard departments established a committee comprising local personalities. This committee was headed by Antoine Borrel, a former minister and the committee's honorary president, and Louis Martel, a former deputy and the committee's president.[Note 14] The festivities encompassed a multitude of formal and informal gatherings across both jurisdictions.[53][54][55][56] In commemoration of the Christmas season of 1959, a Christmas tree was presented to the Paris City Hall. Nevertheless, the most noteworthy events pertained to the pivotal episodes of the 1860 annexation. On March 24, 1960, the anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Turin, the ringing of church bells in Savoy commenced at noon. On the following day, two commemorative postage stamps were released.[Note 15] From March 26 to 28, mayors from the region of Savoy visited Paris, where they were received by Prime Minister Michel Debré.[57] From April 8 to 12, the 85th National Congress of Learned Societies was held in Chambéry and Annecy. On April 12, the recently renovated Annecy Castle served as the venue for a gathering of members of Savoyard learned societies. In celebration of the "plebiscite" on April 22 and 23, a series of festivities were held, accompanied by the bells ringing in various Savoyard parishes. On April 29, the date of publication of the plebiscite results, local newspapers published reproductions of the results. A solemn audience was held in the presence of the minister of justice, Edmond Michelet. In Chambéry, a reading of the April 29, 1860, decree was conducted. To commemorate the treaty ratification on June 12, Sunday was designated a "national holiday" by the authorities, and the bells were rung once more. A commemorative plaque was affixed to the Chambéry City Hall. On June 26, the streets of Chambéry hosted a historical parade with 500 participants, dedicated to Béatrice of Savoie.[58] Throughout the following summer, numerous popular festivals continued the centenary theme, sometimes with illuminations like the one on July 1 at the Nivolet cross. Ultimately, the festivities concluded with the visit of General de Gaulle, President of the French Republic, to Savoy from October 8 to 10.[59] The economic region of the Alpes, which was established in 1956 by the two departments of Savoie and Isère, was subsequently incorporated into the Rhône-Alpes region. 150th anniversary in 2010In commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the annexation, the local authorities of Savoy and Haute-Savoie, in collaboration with learned societies and associations, organized a series of historical conferences, university colloquia, exhibitions, and other events to reach other departments. Additionally, a commemorative website was established for the two departments. Some events, including the carnival, the Savoy Fair, the Saint-Vincent festival, the mountain trades festival, and the Bel-Air festival,[60] adopted the theme of the annexation. Concerts were performed by the Orchestre des Pays de Savoie in some locations in the region. On March 8, the Assembly of the Pays de Savoie (APS) convened with the presence of Senate President Gérard Larcher and National Assembly President Bernard Accoyer, who also serves as the mayor of Annecy-le-Vieux. On March 29, La Poste issued a commemorative stamp for the "Attachment of Savoy to France – Treaty of Turin 1860."[61] On April 21, President Nicolas Sarkozy participated in the plebiscite celebration in Chambéry.[62] On June 12, all the bells of the churches of the Pays de Savoie rang at noon to celebrate the June 12, 1860, union with France. On July 14, the French national holiday, the 10th stage of the Tour de France started from the Savoyard capital. In this year of celebration, on June 6, 2010, Deputy Yves Nicolin posed a question regarding "the significant legal, political, and institutional risks posed by the annexation treaty of Savoy: Whether the annexation treaty of Savoy of March 24, 1860, was registered with the United Nations Secretariat and, if not, what measures the government is taking to address the subsequent legal issues."[63] The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs responded a few days later, on the 15th. The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs has confirmed that the aforementioned treaty remains in force. Although the Treaty of Turin of March 26, 1860, is required to be registered with the United Nations Secretariat under Article 44 of the Treaty of Paris of February 10, 1947, the absence of such registration has no bearing on the treaty's existence or validity.[63] This response differs from the argument put forth by Jean de Pingon, the founder of the Savoie League, which was subsequently adopted by Fabrice Bonnard.[64][65][66][67] The annexation in nationalist discourseAfter the centenary celebrations, many Savoyards were reportedly disappointed with the scale and scope of the festivities. Some mayors who had traveled to Paris expected to be received by President de Gaulle, but this did not happen. However, he did visit Chambéry in October 1960.[68] In 1965, the Club des Savoyards de Savoie, the inaugural significant identity and regionalist movement in Savoy, was established. This identity dynamic reached its zenith during the deliberations surrounding the establishment of new communities in 1972, which culminated in the formation of the Savoy Region Movement and the discourse surrounding the potential creation of a Savoyard region. This could be attributed to the disillusionment of certain individuals or to the pride that these festivities instilled in Savoyards, which provided an opportunity to reaffirm a distinct identity within the broader French context. More recently, the Savoy League has gained momentum in contesting the Treaty of Turin of 1860, challenging the annexation. This movement is sometimes referred to as "disannexionist."[Note 16] In October 2020, a demonstration was held which claimed that the 1860 treaty had been invalid since 1940.[69] See alsoRelated articles about neighboring countries

Notes

References

BibliographyGeneral works

Works on the Annexation

Post-Annexation works

Book on protest

External links

Institutional

Others

Contests

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||