|

Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Anne Spencer Morrow Lindbergh (June 22, 1906 – February 7, 2001) was an American writer and aviator. She was the wife of decorated pioneer aviator Charles Lindbergh, with whom she made many exploratory flights. Raised in Englewood, New Jersey, and later New York City, Anne Morrow graduated from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, in 1928. She married Charles in 1929, and in 1930 became the first woman to receive a U.S. glider pilot license. Throughout the early 1930s, she served as radio operator and copilot to Charles on multiple exploratory flights and aerial surveys. Following the 1932 kidnapping and murder of their first-born infant child, Anne and Charles moved to Europe in 1935 to escape the American press and hysteria surrounding the case, where their views shifted during the preliminary time of World War II towards an alleged sympathy for Nazi Germany and a concern for the United States' ability to compete with Germany in the war with their opposing air power. When they returned to America in 1939, the couple supported the isolationist America First Committee before ultimately expressing public support for the U.S. war effort after the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and subsequent German declaration of war against the United States. After the war, she moved away from politics and wrote extensive poetry and nonfiction that helped the Lindberghs regain their reputation, which had been greatly damaged since the days leading up to the war. She authored the popular Gift from the Sea (1955), and became an inspirational figure for many American women. According to Publishers Weekly, the book was one of the top nonfiction bestsellers of the 1950s.[1] After suffering a series of strokes throughout the 1990s that left her disoriented and disabled, Anne died in 2001 at the age of 94. Early lifeAnne Spencer Morrow was born on June 22, 1906, in Englewood, New Jersey.[2] Her father was Dwight Morrow, a partner in J.P. Morgan & Co., who became United States Ambassador to Mexico and United States Senator from New Jersey. Her mother, Elizabeth Cutter Morrow, was a poet and teacher, active in women's education,[3] who served as acting president of her alma mater Smith College.[4] Anne was the second of four children; her siblings were Elisabeth Reeve,[5] Dwight, Jr., and Constance. The children were raised in a Calvinist household that fostered achievement.[6] Every night, Morrow's mother would read to her children for an hour. The children quickly learned to read and write, began reading to themselves, and began writing poetry and diaries. Anne would later benefit from that routine, eventually publishing her later diaries to critical acclaim.[7] She first attended the Dwight School for Girls in Englewood.[8] After graduating from The Chapin School in New York City in 1924, where she was president of the student body, she attended Smith College from which she graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1928.[4][9] She received the Elizabeth Montagu Prize, for her essay on women of the 18th century such as Madame d'Houdetot, and the Mary Augusta Jordan Literary Prize, for her fictional piece "Lida Was Beautiful".[10] Marriage and familyMorrow and Lindbergh met on December 21, 1927, in Mexico City.[11] Her father, Lindbergh's financial adviser at J. P. Morgan and Co., invited him to Mexico to advance relations between it and the United States.[12] At the time, Anne Morrow was a shy 21-year-old senior at Smith College. Lindbergh was a famous aviator whose solo flight across the Atlantic made him a hero of immense proportions.[9] The sight of the boyish aviator, who was staying with the Morrows, tugged at Morrow's heartstrings. She would write in her diary:

They were married in a private ceremony on May 27, 1929, at the home of her parents in Englewood, New Jersey.[13][4][14] That same year, Anne Lindbergh flew solo for the first time and in 1930 she became the first American woman to earn a first-class glider pilot's license. In the 1930s Charles and Anne explored and charted air routes between continents together, Charles as pilot and Anne as radio (Morse code) operator.[15] The Lindberghs explored polar air routes from North America to Asia and Europe, and were the first to fly from Africa to South America.[16] Their first child, Charles Jr., was born on Anne's 24th birthday, June 22, 1930.[17] Kidnapping of sonOn March 1, 1932, the Lindberghs' first child, 20-month-old Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., was kidnapped from their home, Highfields, in East Amwell, New Jersey, outside Hopewell.[a] Local police began their first search outside the Lindbergh home and found two clear sets of footprints, one leading southeast towards a ladder believed to have been used in the abduction. After the discovery of the ladder, police turned their attention inside the home and searched the nursery. Before calling the police, Lindbergh had found a plain white envelope on the windowsill and, believing it was a ransom note, left it there for the police to examine. Corporal Frank Kelly, an expert in crime-scene photography and fingerprints, was part of the group investigating the child's disappearance. On the envelope, a smudged fingerprint was discovered. Inside the envelope was a detailed ransom note from the kidnapper, demanding $50,000 in cash. The evidence was sent to the state official in charge, Major Schoeffel.[19]

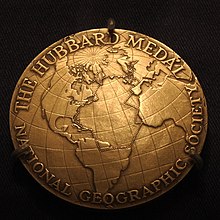

After a massive investigation, a baby's body presumed to be that of Charles Lindbergh Jr. was discovered on May 12, 1932, approximately four miles (6.5 km) from the Lindbergh home, at the summit of a hill on the Hopewell–Mt. Rose highway.[21] Retreat to EuropeThe press paid frenzied attention to the Lindberghs after the kidnapping of their son and the trial, conviction, and execution of Richard Hauptmann for the crime. This—and threats and press harassment of their second son Jon—prompted the family to retreat to the United Kingdom, to a house called Long Barn owned by Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West, and later to the small island of Illiec, off the coast of Brittany in France.[22] While in Europe during the 1930s, the Lindberghs came to advocate isolationist views and an opposition to American involvement in the impending European conflict, which led to their fall from grace in the eyes of many and widespread suspicion that the couple might be Nazi sympathizers. There exists evidence to support that Anne was an admirer of Hitler and shared many of her husband's anti-immigrant and antisemitic views. Anne Morrow's work was part of the literature event in the art competition at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.[23] Return to U.S.In April 1939, the Lindberghs returned to the United States. Because of his outspoken beliefs about a future war that would envelop their homeland, the antiwar America First Committee quickly adopted Charles as its leader in 1940.[12] In 1940, Anne published a 41-page booklet, The Wave of the Future: A Confession of Faith, which "swiftly became the No. 1 nonfiction bestseller in the country."[24] Writing in support of her husband's lobbying efforts for a U.S.-German peace treaty similar to Hitler's Non-Aggression Treaty with Joseph Stalin,[25] Anne argued that the rise of fascism and communism in Germany, Italy, and Russia were manifestations of an inevitable historical "wave of the future",[26] though "the evils we deplore in these systems are not in themselves the future; they are scum on the wave of the future."[27] She compared these movements to the French Revolution for their deplorable violence, but also for their "fundamental necessity". She therefore urged the futility of any ideological war against them.[27] Her writing echoed authors such as Lawrence Dennis and presaged that of James Burnham.[28] The Roosevelt administration subsequently attacked The Wave of the Future as, in an April 1941 speech by Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, "the bible of every American Nazi, Fascist, Bundist and Appeaser", and the booklet became one of the most despised writings of the period;[29][30][31] in December 1940, E.B. White published a much-read and much-quoted critique in The New Yorker that "systematically attacked the logic of its argument."[32] Anne had also written in a letter that Hitler was "a very great man, like an inspired religious leader—and as such rather fanatical—but not scheming, not selfish, not greedy for power".[30] After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and Germany's declaration of war against the U.S., the America First Committee disbanded, and Charles eventually managed to become involved in the military and enter combat only as a civilian consultant, flying 50 missions in this role and even shooting down an enemy aircraft.[33][34] In this period, Anne met the French writer, poet and pioneering aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, author of the novella The Little Prince. Though Anne found "St-Ex" attractive, the two did not have a secret affair, as is sometimes erroneously reported.[35] After Charles Jr., the Lindberghs had five more children: sons Jon, Land, and Scott, and daughters Anne and Reeve.[36][37] Later years and death After the war, Anne wrote books that helped the Lindberghs rebuild the reputations which they had lost before World War II. The publication of Gift from the Sea in 1955 earned her place as "one of the leading advocates of the nascent environmental movement" and became a national bestseller.[38] Over the course of their 45-year marriage, the Lindberghs lived in New Jersey, New York, the United Kingdom, France, Maine, Michigan, Connecticut, Switzerland, and Hawaii. Charles died on the island of Maui in 1974. According to one biographer, Anne had a three-year affair in the early 1950s with her personal doctor.[39] According to Rudolf Schröck, author of Das Doppelleben des Charles A. Lindbergh ("The Double Life of Charles A. Lindbergh"), Anne was unaware that Charles had led a double life from 1957 until his death in 1974. His affair with Munich hat maker Brigitte Hesshaimer produced three children whom he supported financially. After Hesshaimer's passing in 2003, DNA tests conducted by the University of Munich proved that her three children were fathered by Lindbergh.[40] Schröck reported that Brigitte's sister Marietta also bore him two sons. Lindbergh had two more children with his former private secretary. A family reconciliation with the German family members later took place with Reeve Lindbergh being actively involved.[41] After suffering a series of strokes that left her confused and disabled in the early 1990s, Anne continued to live in her home in Connecticut with the assistance of round-the-clock caregivers. During a visit to her daughter Reeve's family in 1999, she came down with pneumonia, after which she went to live near Reeve in a small home built on Reeve's Passumpsic, Vermont, farm, where Anne died in 2001 at 94, following another stroke.[42] Reeve Lindbergh's book, No More Words, tells the story of her mother's last years.[43] Honors and awards  Anne received numerous honors and awards throughout her life in recognition of her contributions to both literature and aviation. In 1933, she received the U.S. Flag Association Cross of Honor for having taken part in surveying transatlantic air routes. The following year, she was awarded the Hubbard Medal by the National Geographic Society for having completed 40,000 miles (64,000 km) of exploratory flying with her husband, Charles Lindbergh, a feat that took them to five continents. In 1993, Women in Aerospace presented her with an Aerospace Explorer Award in recognition of her achievements in and contributions to the aerospace field.[3][13] She was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame (1979), the National Women's Hall of Fame (1996), the Aviation Hall of Fame of New Jersey, and the International Women in Aviation Pioneer Hall of Fame (1999).[3] Her first book, North to the Orient (1935) won one of the inaugural National Book Awards: the Most Distinguished General Nonfiction of 1935, voted by the American Booksellers Association.[44][45] Her second book, Listen! The Wind (1938), won the same award in its fourth year[46] after the Nonfiction category had subsumed Biography. She received the Christopher Award for War Within and Without, the last installment of her published diaries.[47] In addition to being the recipient of honorary master's and doctor of letters degrees from her alma mater Smith College (1935 and 1970), Anne received honorary degrees from Amherst College (1939), the University of Rochester (1939), Middlebury College (1976), and Gustavus Adolphus College (1985).[48] Works

See alsoReferencesNotes

Citations

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Anne Morrow Lindbergh. Wikiquote has quotations related to Anne Morrow Lindbergh.

|

||||||||||||||||||||