|

Anna Chertkova

Anna Konstantinovna Chertkova (maiden name Diterikhs,[Note 1][1][2] September 17 [29],[Note 2] 1859, Kiev, Russian Empire - October 11, 1927, Moscow, USSR) was a children's writer, social activist, folklore collector, memoirist, and a model of Russian group of painters known as The Itinerants (Peredvizhniki).[3] Her literary pseudonyms are "A. Ch." and "A. Ch-va".[4] Anna Diterikhs was born into a family of professional military officers, married Vladimir Chertkov, an important publisher and public figure in the Russian government's opposition, was a close friend of Leo Tolstoy, and was known to her contemporaries as an active propagandist of Tolstoyan movement and vegetarianism. She worked actively in the publishing company "Posrednik" and in the popular magazines of her time "Svobodnoye slovo" and "Listki svobodnogo slova". Anna Chertkova wrote small literary works (one of them was republished 12 times in 24 years), memoirs about Leo Tolstoy and literary articles. She published several editions of religious songs of Russian sect's members. Anna Chertkova was portrayed by Nikolai Yaroshenko in the famous paintings "The Student Girl" (1883) and "In a Warm Land" (1890). Chertkova is also depicted on Mikhail Nesterov's programmatic canvas "In Russia. The Soul of the People" (1916), next to her husband and Leo Tolstoy.[3] BiographyAnna Diterikhs was born in Kiev in the family of a professional military man (then a General of the Infantry, Konstantin Alexandrovich Diterikhs (1823-1899), who had served to the rank of full general. During the Caucasian War, Leo Tolstoy met Diterikhs and used his "Notes on the Caucasian War" to write "Hadji Murat". Anna's mother was the aristocrat Olga Iosifovna Musnitskaya (1840-1893).[5] Anna was the eldest daughter and second child of the family. In the early 1860s, Anna's family lived on the Volga River in a two-story wooden house with a mezzanine and a front garden in the town of Dubovka. She later described in her childhood memoirs her strong impression of the fires that took place there in 1861-1862 and her fear of the arsonists, who were never discovered. The girl preferred to walk barefoot and did not pay much attention to clothes, especially bright colors. Later she remembered that as a child she wanted to be a boy. Among the most pleasant impressions of her childhood, she emphasized music and especially singing. According to Diterikhs, music "hypnotized" her. In the family, the girl was called Galya, not Anna, according to the order introduced by her maternal grandfather, General Osip Musnitsky, according to her memoirs, half-Polish, half-Lithuanian.[6] Her mother was a deeply religious person, a firm supporter of Orthodoxy, while her father, who lived for a long time in the Caucasus, was interested in Islam as well as Christian sects: the studies of the Molokans and Dukhobors.[7][Note 3]

In Kiev, the girl was a student at the gymnasium (secondary school) and seriously studied music.[8] In 1878, Anna entered the verbal department of the higher Bestuzhev courses in St. Petersburg,[Note 4] but two years later transferred to the natural department. Historian Georgy Orekhanov claimed that Anna Dieterichs was a fellow student of Nadezhda Krupskaya at Bestuzhevsky courses.[9] After graduating in 1886, Diterikhs was not able to get a diploma of its completion. After four years of study, she fell seriously ill and missed the final exam.[1][Note 5] During her studies she became interested in materialism, positivism and Johann Gottlieb Fichte's studies.[3] It is reported by the Russian religious philosopher Nikolai Lossky that Anna Dieterichs used to work for some time as a teacher in a private female secondary educational institution in St. Petersburg, the Gymnasium of M. N. Stoyunina, where her younger sisters Olga and Maria were studying.[10]   Since 1885 Diterikhs began to participate in the work of the publishing house "Posrednik", where she was introduced by the public figure and publicist Pavel Biryukov.[1] "Very painful and fragile, acutely experiencing every new impression, demanding and serious, A. K. Diterikhs was attracted to people and soon became a necessary worker in the new publishing house", - wrote about her Mikhail Muratov.[11]  There she met Leo Tolstoy[1] and Vladimir Chertkov, whom she soon married. At "Posrednik" she worked as an editor and proofreader and also handled correspondence. At the same time, Diterikhs wrote[3] and contributed to her husband's publishing activities. The Chertkovs lived in the 1890s on the Rzhevsk khutor (Vladimir Chertkov's uncle's gift to him), which consisted of a manor house on a mountain, a large farm, and numerous buildings. Rzhevsk was a lonely place, surrounded by fields and steppes. The land was rented. There were many servants, workers, coachmen and craftsmen on the estate. The literary and organizational affairs of "Posrednik" took place here.[12] In 1897, Chertkov was exiled from Russia. The couple left with their entire family. With them went Vladimir Chertkov's mother, two maids who had lived with them for many years - Anna, who had served in their house since her early youth, and her son's nanny Katya, as well as the house doctor Albert Shkarvan, an Austrian maid of Slovakian nationality.[13] While living in Great Britain from 1897 to 1908, Anna Chertkova worked with her husband in the publishing house "Svobodnoe Slovo". In her autobiography, she wrote that although she was listed as a publisher, she actually performed the duties of a proofreader, office assistant, compiler and editorial assistant, wrote editorial notes, compiled the number of issues of "Svobodnoe Slovo", communicated with the printing house, etc.[1] When the publication of "Svobodnoe Slovo" was transferred by Biryukov to Switzerland, the Chertkovs concentrated on the publication of "Listki Svobodnoe Slovo".[14] A contemporary describes Tuckton House, where the Chertkovs lived in Christchurch, as very strange and uncomfortable. It had three floors in some parts and four in others, built of brick and all covered with ivy. There was a staircase in the center of the building, with doors to many rooms on the right and left sides. There was a special steel storeroom for Tolstoy's manuscripts, equipped with an alarm system. All the rooms were isolated and did not communicate with each other, except for fireplaces, there was no other heating, and Anna Chertkova suffered from cold in winter. There were 30-40 people living in the house at the same time: Russians, Latvians, Estonians, Englishmen, who had different beliefs: there were Tolstoyans, social democrats, socialist-revolutionaries: "They were all doing something, working, and life was full and interesting. On certain days of the week, the Chertkovs fed English vagabonds. The printing house of "Svobodnoe Slovo" was near the Tuckton house.[15] After returning from Great Britain, the couple settled in the Tula province. Their house in Telyatinki became the center of attraction for the Tolstoyans. According to a contemporary, they felt more at home there than in Yasnaya Polyana, "where they were bound by the strange arictocratic ambience. Son Vladimir was closely associated with the peasant youth. Chertkovy quickly attracted the attention of the local administration, and were denounced. Since October 1908, the couple had been under silent surveillance.[16] Their house was located three kilometers from Yasnaya Polyana, it was wooden, two-storied and, according to a contemporary, uncomfortable. Tolstoy called it a "beer factory". On the ground floor was a large dining room, behind which were corridors in both directions, each of which led to four small rooms. In the middle of the second floor was a hall with a stage for amateur performances. There were 34 rooms in all. Almost all of them were filled with guests. There was no terrace, flower garden, river or pond around the house.[17] Anna Chertkova was seriously ill. Tolstoy admired her resilience and considered her one of those women for whom "the highest and living ideal is the coming of the Kingdom of God".[3] In the 1920s, she was engaged in sorting and describing the writer's manuscripts for the publication of his Complete Works. She also wrote a scholarly commentary on Leo Tolstoy's correspondence with her husband.[18] Anna Chertkova died in Moscow in 1927.[3] She was buried next to her husband in the Vvedenskoye cemetery (section 21). Anna Chertkova was portrayed by N.A. Yaroshenko in the paintings "Student" (1883) and "In a Warm Land" (1890). Yaroshenko's biographer, the chief researcher of his Memorial Museum Irina Polenova wrote that Chertkova also became a comic figure in the artist's graphics. According to the researcher, Yaroshenko found in Anna Chertkova "the correspondence to various and even mutually exclusive of his plans".[19] Chertkova is depicted on Mikhail Nesterov's paintings "In Russia. Soul of the People" (1916) next to her husband and Leo Tolstoy[3] as well as in two portraits he completed in 1890.[20] Literary work and contribution to her husband's career in publishing Among Anna Chertkova's prerevolutionary works is an adaptation of the Hagiography of St. Philaretos (1886).[21] Doctor of philology Anna Grodetskaya stated that Tolstoy's correspondence with A.K. Diterikhs, connected with the censorship's permission to print the Hagiography, prompted the writer to create a treatise "On Life". She also noted that the problem of St. Philaretos's care for his neighbors and his wife's care for her family reflected Tolstoy's thinking at that time. To this problem he devoted chapter 23 of his treatise.[22] Leo Tolstoy became acquainted with Chertkova's work a year before it was published in manuscript. His evaluation in a letter to Vladimir Chertkov has been preserved: "I received the hagiography of St. Philaret. It is beautiful. I will not touch it. - Very good".[23] In one of his letters he asserted: "Diterikhs put a lot of her inner feeling into it and it came out touching and convincing".[24] Chertkova is the author of a short text for children, "The Heroic Story" (first published in 1888, by 1912 there were already 12 editions). In the story the rich elderly merchant Mahmed-Ali has two sons. The elder, Jaffar, goes to war and becomes a great commander, but his father rejects his fame. He then rejects his greatness as a scholar, writer, and dervish. Mehmed-Ali's youngest son, Nuretdin, is captured. He loses all his wealth. Jaffar goes to the enemies he once defeated. He offers to give himself in exchange for his younger brother. They release Nuretdin and send Jaffar to prison, but keep him alive. When Nuretdin tells the story of his release, his father exclaims: "Only now have you [Jaffar] achieved true greatness and immortality: you have done it for others, forgetting yourself![25]  In 1898, Anna Chertkova published a book. It contained three stories: "Quail" (a young peasant accidentally kills a young quail that got under his scythe), "Vadas" (a hound brings his masters a starving dog after his master's death), "The Story of My Friend About How He Was No Longer Afraid of Thunderstorms" (a seven-year-old boy, in whose name the story is written, runs out of the house during a thunderstorm to save a kitten thrown out the door).[26] She also wrote the children's story "One Against All" (1909, a ten-year-old boy - the son of a landowner, having heard the story of a stable boy about how he slaughtered a pig, refuses to eat meat), the article "How I became a vegetarian" (1913),[27] a collection of memoirs "From My Childhood. Memories of A. K. Chertkova" (1911).[28] Anna Chertkova wrote poems embodying the ideals of the Tolstoyan movement during her time in Rzhevsk.[29]

In 1900, Chertkova wrote "A Practical Textbook of the English Language, Intended for Russian Settlers in America".[30] She compiled a collection of various religious hymns by Russian sectarians: "A Collection of Songs and Hymns of Free Christians" (1904-1905, three editions). In the preface, Chertkova noted that some of the published texts actually belonged to free Christians, while others were "intended to satisfy their needs" for "spiritual songs" that corresponded to their "understanding of life"; thus, many of the texts were actually written by Russian poets such as Alexey Tolstoy, Alexander Pushkin and Alexey Khomyakov, and the melodies were taken from Russian folklore or works by well-known Western composers such as Ludwig van Beethoven and Frederic Chopin; the songs were published in a two-handed version for voice and clavichord).[31] Another collection compiled by Chertkova was "What Russian Sectarians Sing" (three editions, 1910 - 1912, containing authentic songs of Russian sectarians; Cherkova said she obtained their approval of each recording by performing the music herself in their presence), She published psalms and "verses" of the Dukhobors in the first edition, "psalms" of the Malyovans in the second edition, and songs of the Yakut sectarians, Oskoptsy, Molokans, Dobrolubovians, and "Old Israel" in the third edition).[32] Another collection was of songs and canons was called "Melodies" (in four editions, ca. 1910), Rural Sounds (c. 1910), and "The Sower" (1922). She also published her own recording of the folk song "About Moscow in 1812" (1912); she became the author of the words and music for the songs "Listen to the Word, the Dawn is Breaking" and "The Day of Freedom is Coming" popular among the "Tolstoyans".[3][33][Note 6] Leo Tolstoy's secretary, Valentin Bulgakov, described the songs in the collections as "monotonous and dull," in which "even the calls for brotherhood and freedom sounded in a mournful minor key. At the same time, he praised Anna Chertkova's performance skills, finding her "thick, beautiful timbre and well-placed contralto". "Her "crowning" works were an aria from Christoph Willibald Gluck's "Iphigenia" and a song to words by Alfred Tennyson, translated by Aleksey Pleshcheyev, "Pale Arms Crossed on the Chest",[34] which she herself set to Beethoven.[35] Chertkova wrote literary essays on some aspects of Tolstoy's way of working: "L. N. Tolstoy and his acquaintance with spiritual and moral literature. According to his letters and personal memories of him" (1913, in this article Chertkova refuts the widespread opinion that Leo Tolstoy was prejudiced against Orthodoxy and therefore made no attempt to seriously familiarize himself with the writings of the Church Fathers)[36] and "Reflection of the thinking process in the 'Diary of Youth'" (1917).[3] During the Soviet period her memoirs about the writer "From the Memories of L. N. Tolstoy" (2626) were published. Tolstoy" (1926, in this work Chertkova recalled meetings with the writer in 1886, spoke in detail about how she performed for Tolstoy vocal works by George Frideric Handel, Alessandro Stradella, Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Gluck, and once Tolstoy himself accompanied her in the performance of old Russian romances)[37][38] and "The first memories of L. N. Tolstoy" (1928).[39] Personality and personal lifeAnna Chertkov's familyBefore proposing to Anna Diterikhs, Vladimir Chertkov told Tolstoy, who knew her well and approved of the marriage.[40] Anna Diterikhs became Vladimir Chertkov's wife on October 19, 1886.[41][1] Their wedding took place in St. Petersburg's Kazan Cathedral.[Note 7] Soon Tolstoy wrote to the couple, "I love you and feel happy for you. Vladimir Chertkov replied that he "feels complete unity with his wife, becomes a better man with her and goes forward more successfully than without her".[42] In the original text of her husband's biography, which Anna wrote together with Alexei Sergeenko, it is said:

Before proposing to Anna Diterikhs, Vladimir Chertkov told Tolstoy, who knew her well and approved of the marriage.[40] Anna Diterikhs became Vladimir Chertkov's wife on October 19, 1886.[41][1] Their wedding took place in St. Petersburg's Kazan Cathedral. Soon Tolstoy wrote to the couple, "I love you and feel happy for you. Vladimir Chertkov replied that he "feels complete unity with his wife, becomes a better man with her and goes forward more successfully than without her".[42] In the original text of her husband's biography, which Anna wrote together with Alexei Sergeenko, it is said:  Later, Chertkova crossed this fragment out of the text with the note: "It is inappropriate at all. A. Ch.".[41] Vladimir Chertkov himself wrote about his wife: "I have always felt guilty for the happiness that was somehow my share - the happiness of being together with my wife - a sister in spirit, a comrade and helper in everything I do and in the way I see life.[43] The Chertkovs had two children.[44]

Anna Chertkova's personality according to her contemporaries Anna Chertkova's personality was described and evaluated in different ways by her contemporaries. Pavel Biryukov, a long-time employee of "Posrednik", wrote: "This is a young girl, gentle, pretty... she met me... only to help us, and she really helped".[7] The Russian State Archive of Literature and Art has Leo Tolstoy's signed review: "Anna Konstantinovna and Vladimir Grigorievich Chertkovy are my closest friends, and I not only always approve of all their activities concerning me and my works, but they also arouse in me the most sincere and deepest gratitude. Leo Tolstoy. January 28, 1909" (F 552. Op. 1. D 2863. Review of L. Tolstoy about Chertkovs. L. 1).[53] Valentin Bulgakov described Chertkova's appearance, calling her "a small, thin woman, with intelligent and kind, but restless and anxious (as if she had some kind of sadness or fear in her soul) black eyes and a mop of short-cropped and slightly graying black hair on her head".[54] He believed that Anna was the opposite of her husband: "Softness and even almost weakness of character, hardness of will, cordiality, modesty, sensitivity, attentive sympathy for the interests, sorrows and needs of neighbors, warm hospitality, a lively feminine curiosity about everything leading beyond the limits of the 'Tolstoyan' horizon".[35] According to him, Chertkova did not play an independent role, although in intelligence and cultural development she far surpassed her husband.[55] She shared Tolstoy's views, was a loyal assistant and friend of Vladimir Chertkov.[56] Bulgakov called her "lovely... but intimidated by life and her husband", a "vigorous and interesting" personality.[55] Chertkova was intimidated by her husband. She refused to acknowledge his guilt in relation to herself or anyone else, in anything wrong, always supported his opinion. Bulgakov noted that if the surrounding people were afraid of Vladimir Chertkov, his wife was loved by everyone, with whom she established "simple, trusting, friendly relations".[54] Mikhail Nesterov also regretted that Vladimir Chertkov oppressed his wife "by his blunt will".[5] Bulgakov wrote that Anna was bored because the household was run by a housekeeper. Therefore, she tried to fill everyday life with something: reading correspondence, answering to Tolstoyans, reading aloud, proofreading, chatting. As for Chertkova's illness, he claimed that "90%" of it was "fictitious". Bulgakov described its significance as the ability to "introduce the uncertain, weighty scope of his [Vladimir Chertkov's] heavy character into a more or less acceptable, disciplining framework, and also to facilitate access to him for other people - both those who lived with him under the same roof and those who appeared in his house for the first time".[57] On the contrary, the memoirist Sofya Motovilova was very negative about Chertkova.[5] Motovilova wrote:

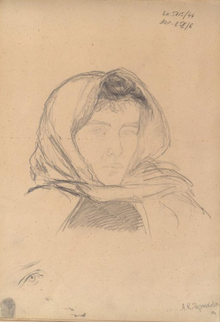

Anna Chertkova in the paintings of Nikolai YaroshenkoNikolai Yaroshenko knew Anna Chertkova well and corresponded with her. There are two published letters from Yaroshenko to Chertkova: from November 8, 1894 from Kislovodsk[59] and from January 9, 1896 from St. Petersburg,[60] as well as a letter addressed to both spouses simultaneously from December 8, 1897 from St. Petersburg.[61] The artist was interested in her health and her son's achievements in numerous letters to Vladimir Chertkov.[62] In the collection of the Memorial Museum of N. A. Yaroshenko there is a photograph of Vladimir and Anna Chertkovs, who were at the artist's summer house in Kislovodsk in 1890.[63] There are also the drawings of Anna Chertkova made by the artist in that year: "A. K. Chertkova on the balcony" (paper, Italian graphic pencil, 17.5 × 13.3 cm, the drawing is signed by son Vladimir "Sketch of my mother by Yaroshenko")[64] and "Chertkov family friendly caricature" (paper, cardboard, graphic pencil, 20 × 23 cm).[65] "Student" Anna Chertkova was portrayed by Nikolai Yaroshenko in the painting "Student", created in 1883. A version of this painting is kept in the collection and exposition of the Kaluga Fine Arts Museum (inventory Ж 0167).[66] Oilpainting over linen. Its dimensions are 131 × 81 cm.[67] A variant of the painting, which is in the collection and exposition of the National Museum "Kiev Art Gallery" (inventory Ж-154),[68] is made in the same technique. Its size is 133 × 82,5 cm (according to other data - 134 × 83 cm).[68] It is signed: "N. Yaroshenko 1883".[67] There are different opinions about whether the painting reflects Chertkova's personality and appearance. Vladimir Prytkov, a doctor of art history, believes there is no doubt that the artist painted Anna Konstantinovna Diterikhs. At the same time, he noticed that Yaroshenko made his model younger. Instead of the real 24 years, she can be given 17-18 in the picture.[Note 9][8][69] The same opinion was expressed by Alla Vereshchagina, Doctor of Art History, Academician of the Russian Academy of Arts. She wrote that the artist retained the most common features of Chertkova's face, but made her much younger.[70] The role of Diterikhs was assessed differently by Irina Polenova, the chief researcher of the N.A. Yaroshenko Memorial Museum. She wrote that Diterikhs gave only "some, but noticeably changed, of her features to the 'student'".[19] In her article of 2018, without even mentioning Diterikhs, she wrote about "the real appearance of thousands of contemporaries", which, according to her, is the basis of the protagonist's life.[71] The cultural historian Vladimir Porudominsky saw the reflection of several real women in the figure depicted in the painting: Maria Nevrotina - the artist's wife, a student of the first Bestuzhev courses; Nadezhda Stasova, a friend of the artist, a public figure, the sister of the music and art critic Vladimir Stasov, the wife of Yaroshenko's brother Vasily; Elisabeth Schlitter, a lawyer by training, a graduate of the University of Bern; and, above all, Anna Dieterichs, whom he considered the prototype of the heroine of the painting. In Porudominsky's opinion, the artist, while working on the painting, gradually eliminated the likeness of his heroine to Dieterichs, thus achieving the transformation of the prototype into a type.[72] The art historian noted that contemporaries who knew Anna Chertkova did not recognize her image in the painting "Student".[73] "In a Warm Land" In 1890, the artist portrayed Anna Chertkova in his painting "In a Warm Land" (Russian Museum, inv. Ж-2500, canvas, oil, 107.5 × 81 cm, in the lower right corner of the painting signed and dated by the author: "N. Yaroshenko. 1890").[74] Another version of the painting is in the collection of the Yekaterinburg Museum of Fine Arts.[75] The painting "In a Warm Land" Nikolai Yaroshenko wrote in Kislovodsk in the White Villa. Anna Chertkova is portrayed as a pale, sad and sickly woman, alone and languishing in the lush southern nature.[76] At that time, Yaroshenko himself was suffering from a severe form of tuberculosis. In a letter to Anna Chertkova he reported: "For a month and a half I looked like an almost motionless and useless body, I could only lie or sit in an armchair, in cushions ... like you in the picture I painted of you". Soviet art historian Vladimir Porudominsky wrote that the painting's heroine "turned out to be a beautiful lady with exquisitely correct features (expressing less her or the artist's suffering than the desire to make them 'touching'), with thin, graceful hands that she deliberately shows...".[77] [75] Contemporaries who knew Anna Chertkova perceived the painting "In a Warm Land" as a traditional portrait (although, according to Porudominsky, it contains a more complex plot).[73] Ilya Repin wrote to Chertkova: "At the exhibition I liked very much the portrait of Anna Konstantinovna recovering (by Yaroshenko). Expressively and subtly written. A beautiful thing".[73][75] Leo Tolstoy saw the canvas "In a Warm Land" at Yaroshenko's posthumous exhibition and called it "Galya in Kislovodsk". Visitors to the exhibition who did not know Chertkova pitied the beautiful lady who, in their opinion, was destined to leave the earthly world.[73] The Leo Tolstoy State Museum has a pencil drawing by Vladimir Chertkov (1890, paper, pencil, is in the album of drawings by Vladimir Chertkov), on which he portrayed Nikolai Yaroshenko at work on the painting "In a Warm Land".[78] N.V. Zaitseva in her article mentioned that Chertkov made sketches and the painting itself, as well as his wife.[79] Anna Chertkova in the paintings of Mikhail NesterovSketches from 1890 The artist Mikhail Nesterov met Vladimir Chertkov in 1890 in the house of Nikolai Yaroshenko in Kislovodsk. The oil portraits of Chertkov himself and his wife belong to this period.[Note 10][80][81] These are: "Portrait of Anna Konstantinovna Chertkova" (sketch, 1890, canvas, oil. 31 × 19 cm, Leo Tolstoy State Museum, Moscow, inventory АИЖ-396) and "Portrait of Anna Konstantinovna Chertkova" (1890, canvas, oil. 40 × 26 cm, Leo Tolstoy State Museum, Moscow, inventory number АИЖ-397). Art historian Irina Nikonova, in her monograph on the work of Mikhail Nesterov, insisted that these portraits were not an expression of his worldview, but a consequence of the artist's desire to capture close and beloved people.[20]  Nadezhda Zaitseva considered a portrait of Anna and a portrait of her husband, painted in Kislovodsk, to be a pair. The format, the coloring, the composition (the portraits are facing each other) and the psychology of the dialog between the characters are the same. Chertkova's hair is careless, she has shadows under her eyes, her lips are open as if she were whispering a prayer, and her eyes seem to be full of tears. According to Zaitseva, the artist conveyed a state close to prayer or ecstasy. In the portrait of his wife, Nesterov conveyed the strength and authority of a fanatical priest. Chertkova seems to submit to her husband's will (Nesterov himself wrote about this in one of his letters).[5][82] "In Russia. The Soul of the People""In Russia. The Soul of the People" (canvas, oil on canvas, 206 × 484 cm, State Tretyakov Gallery) - the painting, on which the artist worked in 1914-1916, is a picture of Russian life as it seemed to Nesterov at that time. On the canvas before the viewer appears the bank of the Volga near Tsaryov Kurgan (a place in the bend of the Volga near Zhiguli). A crowd of people is moving slowly along it. The canvas gives a panorama of the Russian people, there are representatives of all estates of the realm and social classes, from the tsar to a fool and a blind soldier, in this crowd were depicted Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Vladimir Solovyov. In the foreground there is a boy in peasant clothes with a basket behind his back and a bowl in his hand. The artist has created a historical group portrait of people searching for the truth and going to it in different ways. Irina Nikonova suggested that Nesterov was drawing on views that were widespread in philosophical circles at the time, calling for "the idea of the individual and the idea of the nation to replace the idea of intellectuals and classes" as the basis of the social worldview. At the same time, he preached moral purity and mental clarity, seeing in them the meaning of life and the reconciliation of different religious movements. The painting provoked heated debates in the Psychological Society of Moscow University and the Society in Memory of Vladimir Solovyov.[83] Anna Chertkova is depicted on the canvas next to her husband and Leo Tolstoy.[3] Nadezhda Zaitseva emphasized that in this painting Nesterov portrayed Anna Chertkova as a full-fledged character, a person searching for her God and ideals. For the picture he used a sketch from 1890. Zaitseva found it remarkable that Vladimir Chertkov was not on the canvas "even among the 'deluded'", she assumed that the artist did not refer him to people of "living faith".[82]  Other portraits of Anna Chertkova  In 1881, Grigory Myasoedov, a member of the Peredvizhniki movement, portrayed the young Anna Dieterichs, who was then a student at the Bestuzhevsky Courses (canvas, oil on canvas, 49.0 × 38.0 cm, The Tolstoy Estate Museum "Yasnaya Polyana", inventory Ж-195). The girl is portrayed in a dark gray dress with a white collar to which a small dark red brooch with a short chain is attached. Her thick black hair is slicked back and falls to her shoulders. The girl has a high forehead, dark eyes under thick arched eyebrows, and a light blush on her cheeks.[84] The Leo Tolstoy State Museum has a group of sketches made by Vladimir Chertkov about the appearance of his wife. One of them (paper, pencil, 33 × 23 cm, inventory number АИГ-858/6) was made in the 1890s in Chertkov's album, probably in Kislovodsk. In the central part of the sheet, the amateur artist portrayed his wife in a head and shoulders portrait. She is wearing a shoulder-length shawl. Below her portrait, in the lower left corner, there is a face with only the eyes and eyebrows drawn.[84] On another page of the same album by Vladimir Chertkov are "Two Sketches of a Portrait of A. K. Chertkova" (date unknown, paper, pencil, 23 × 33 cm, inventory АИГ-858/8). The images of two female faces are located in the central part of the sheet, one below the other. Both images of a woman are of head and shoulders length, her hair is luxuriant, but she has a short haircut. The upper one is in profile, the lower one is turned 3/4 to the right and the detached collar of the blouse is clearly visible.[84] Another portrait of Anna Chertkova belongs to graphics artist Mikhail Rundaltsov. On the etching "Tolstoy's Head with a Portrait Note of Tolstoy and A. K. Chertkova at the Table" (1908, 55 × 45.5 cm, The State Museum of Leo Tolstoy, inv. AIG-1197), she is shown in the lower right corner, talking with the writer.[85] Notes

References

BibliographyAnna Chertkova's writings

Sources

Academic and general interest titles

|

||||||||||||||||