|

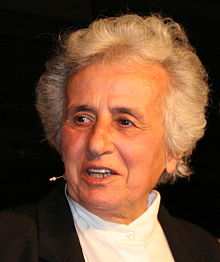

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch

Anita Lasker-Wallfisch (born 17 July 1925) is a German-British cellist, and a surviving member of the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz.[1][2] FamilyLasker was born into a German Jewish family in present-day Wrocław, Poland, then-Breslau, Germany. She has two sisters, Marianne and Renate. Her father Alfons was a lawyer and her mother a violinist. Her uncle was noted chessmaster Edward Lasker.[2] Lasker's father fought in the German war front in World War I, gaining an Iron Cross. His participation in German military gave the family a false sense of immunity from Nazi persecution, and they suffered discrimination in the 1930s as the Nazis rose to power.[1] World War IIHer eldest sister, Marianne, was able to escape the Holocaust by being sent away on the Kindertransport to England in 1939.[3] In April 1942, Lasker's parents were taken away and are believed to have died near Lublin in Poland.[1] Anita and Renate were not deported as they were working in a paper factory. There they met French prisoners of war and started forging papers to enable French forced labourers to cross back into France.[1]

In September 1942 they tried to escape to France, but were arrested for forgery by the Gestapo at Breslau station. Only their suitcase, which they had already put on the train, escaped. The Gestapo were anxious about its loss, and carefully noted its size and colour.[1]

Concentration campsAnita and Renate were sent to Auschwitz in December 1943[4] on separate prison trains, a far less squalid way to arrive than by cattle truck, and less dangerous, since there was no selection on arrival.[2] Playing in the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz saved her,[5] as cello players were difficult to replace. The orchestra played marches as the slave labourers left the camp for each day's work and when they returned. They also gave concerts for the SS.[1] By October 1944, the Red Army were advancing and Auschwitz slowly started getting evacuated. Anita was taken on a train with 3,000 others to Bergen-Belsen[4] and survived for six months with almost nothing to eat.[2] After the liberation by the British Army she was first transferred to a nearby displaced persons camp. Her sister Renate, who could speak English, became an interpreter with the British Army.[1] During the Belsen Trial, which took place from September to November 1945, Anita testified against the camp commandant Josef Kramer, camp doctor Fritz Klein, and deputy camp commandant Franz Hössler, who were all sentenced to death and hanged that year.[4] Post-warIn 1946, Anita and Renate moved to Great Britain with the help of Marianne.[1][2] Anita married the pianist Peter Wallfisch and is mother to two children;[2] her son is the cellist Raphael Wallfisch, and her daughter, Maya Jacobs-Wallfisch, is a psychotherapist. Wallfisch co-founded the English Chamber Orchestra (ECO),[6] performing as both a member and as a solo artist, and toured internationally. Her grandson is the composer Benjamin Wallfisch. After nearly 50 years away from Germany, she finally returned there on tour with the ECO in 1994. Since that time, and as a witness and victim of the Nazi period, she has visited German and Austrian schools to talk about and explain her experiences.[7] On this note, she promotes the work for the New Kreisau, in Poland, as well as the work of the Freya von Moltke Foundation and the Kreisau Circles legacy.[8] In 1996 she published her memoir Inherit the Truth.[9] Over the years, Lasker has told her life-story in numerous oral history interviews, for example in the Shoah Foundation's Visual History Archive (1998) and the online archive Forced Labor 1939–1945 (2006).[10] She was interviewed by National Life Stories (C410/186) in 2000 for 'The Living Memory of the Jewish Community' collection held by the British Library.[11] In 2011, Lasker received an Honorary degree as Doctor of Divinity from Cambridge University.[6] In 2018, Lasker gave a commemorative speech in the Bundestag to mark the 73rd anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.[3] In December 2019 Lasker was part of a 60 Minutes story about the music written and performed by prisoners in Auschwitz being preserved by Francesco Lotoro.[12] In December 2020 Lasker was awarded the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, which was conferred by the Federal President, Frank-Walter Steinmeier.[13] The coronavirus pandemic delayed the presentation of the award until 20 May 2021, when Andreas Michaelis, the German Ambassador in London, presented it in a small informal event at his residence. Paraphrasing the presidential award, Michaelis commented: "To this day, you have helped keep the memory of the Holocaust alive for future generations. Germany is profoundly grateful to you for this."[14] Lasker stars in the 2024 documentary film The Commandant's Shadow, together with Jurgen Höss, the son of Auschwitz concentration camp director Rudolf Höss. The film includes Lasker's meeting with Jurgen Höss, accompanied by Lasker's daughter Maya Lasker-Wallfisch and Höss's son Kai Höss, both of whom have major roles in the documentary.[15][16] References

|

||||||||||||||||||