|

Anechoic tile

Anechoic tiles are rubber or synthetic polymer tiles containing thousands of tiny voids, applied to the outer hulls of military ships and submarines, as well as anechoic chambers. Their function is twofold:

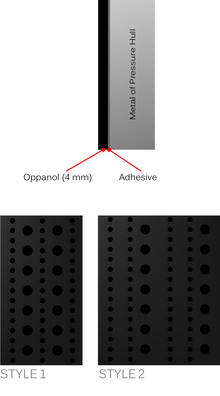

Development in the Third Reich The technology of anechoic tiles was developed by the Kriegsmarine during the Second World War, codenamed Alberich after the invisible guardian dwarf of the Rhinegold treasure from Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen music dramas. The coating consisted of sheets approximately 1 m (3 ft 3 in) square and 4 mm (0.16 in) thick, with rows of holes in two sizes, 4 mm (0.16 in) and 2 mm (0.079 in) in diameter.[1][2][3] Manufactured by IG Farben as a specially formed synthetic rubber tile and made using a stabilized, non-polar, high molecular weight polyisobutylene homopolymer with low-temperature elasticity; the rubber material itself was known by its trademark Oppanol.[1][2][4] The material was not homogeneous, but contained air cavities; these cavities resulted in a degraded reflection of ASDIC.[5] The coating reduced echoes by 15% in the 10 to 18 kHz range.[1] This frequency range matched the operating range of the early ASDIC active sonar used by the Allies. The ASDIC types 123, 123A, 144 and 145 all operated in the 14 to 22 kHz range.[6][7] However, this degradation in echo reflection was not uniform at all diving depths due to the voids being compressed by the water pressure.[8] An additional benefit of the coating was it acted as a sound dampener, containing the U-boat's own engine noises.[1]  The coating had its first sea trials in 1940, on U-11, a Type IIB.[1][5] U-67, a Type IX, was the first operational U-boat with this coating.[2] After its first war patrol, it put in at Wilhelmshaven probably sometime in April 1941 where it was given the coating. The coating covered the conning tower and sides of the U-boat, but not to the deck. By 15 May 1941, U-67 was in Kiel performing tests in the Baltic Sea. During July, the coating was removed from all parts of the boat except the conning tower and bow. Further experiments and sound trials were made in the Little Belt but they presumably proved unsatisfactory, as all the coating was subsequently removed.[9] Problems were encountered early-on, when it was found that the adhesive had insufficient strength to bond synthetic rubber with the pressure hull and casing.[3][5] This resulted in the sheets loosening and creating turbulence in the water, making it easier for the submarine to be detected.[10] Furthermore, the coating was found to have considerably decreased the speed of the boat.[2][11] It was not until late 1944 that the problems with the adhesive were mostly resolved. The coating required a special adhesive and careful application; it took several thousand hours of glueing and riveting on the U-boat.[12] The first U-boat to test the new adhesive was U-480 a Type VIIC.[1][5] With good results with the new adhesive, the Oberkommando der Marine intended that it would be widely used on the new Type XXI and Type XXII U-boats. However, the war ended before it could be put into large scale use.[5] Ultimately only one operational Type XXIII, U-4709, was coated with the anechoic tiles.[1] U-boats with the anechoic tiles coating include: U-11, U-480, U-485 U-486, U-1105, U-1106, U-1107, U-1304, U-1306, U-1308, U-4704, U-4708 and U-4709.[13][14][15][16] Anechoic coating based on research & technology supplied by Germany was also used by the Japanese I-400-class submarines, though completely different in composition from German rubber-based tiles like Alberich or Tarnmatte. Modern day usageAfter the war the technology was not used again until the late 1960s when the Soviet Union began coating its submarines, starting with the Victor class, in rubber tiles.[17] These were initially prone to falling off, but as the technology matured it was apparent that the tiles were having a dramatic effect in reducing the submarines' acoustic signatures. Modern Russian tiles are about 100 mm thick, and apparently reduced the acoustic signature of Akula-class submarines by between 10 and 20 decibels, (i.e. 10% to 1% of its original strength).[citation needed] Modern tiles[when?] may consist of several layers of material with voids of variable sizes, designed to mask and deflect specific sound frequency ranges at different depths. Different materials[which?] may be used by marine engineers to cover sections of the submarine where they are needed to absorb specific frequencies associated with machinery at that location inside the hull.[citation needed] The Royal Navy started using anechoic tiles in 1980, when HMS Churchill was fitted with them during its second refit.[18] The United States Navy also started using anechoic tiles in 1980, with USS Batfish.[19] In recent years, nearly all modern military submarines are designed to use anechoic tiles.[citation needed] See also

ReferencesNotes

|